Early last century, Hilferding identified a new stage of capitalism characterized by complex financial relations and domination of industry by finance. He argued the most characteristic features of finance capitalism is rising concentration which, on the one hand, eliminates ‘free competition’ through the formation of cartels and trusts, and on the other, brings bank and industrial capital into an ever more intertwined relationship. Veblen, Keynes, and, later, Minsky also recognized this new stage of capitalism: for Keynes, it represented the domination of speculation over enterprise while Veblen distinguished between industrial and pecuniary pursuits. Veblen, in particular, argued that modern crises can be attributed to the “sabotage of production” (or “conscientious withdrawal of efficiency”) by the “captains of industry”.

Much of this description of the finance capitalism stage can be applied to the current phase of capitalism—the money manager stage. Indeed, the intervening years, from the New Deal until the early 1970s, should be seen as an aberration. That phase of capitalism was unusually quiescent—the era of John Kenneth Galbraith’s “New Industrial State”, when the interests of managers were more consistent with the public interest. Unfortunately, the stability was interpreted to validate the orthodox belief that market processes are naturally stable—that results would be even better if constraints were relaxed. As New Deal institutions (broadly defined) were weakened, a new form of finance capitalism came to dominate the US and global economies. This is what Minsky called money manager capitalism—and what I am arguing is simply a return to finance capitalism. Finance capitalism is the normal version of modern capitalism. The Golden Age of capitalism was not normal.

2- Most of the analysts refer to a neo-liberalism approach dominant from the emergence of the monetarist school. But it seems – particularly since the end of the 1980s – that this second wave of the financial capital was driven by a “mix” of neo-keynesian and monetarist thoughts, an interesting new species in economic and financial though and ideology, whose “agent” of excellence was the Maestro Mr Greenspan. The acceleration of this second financial wave is “transversal” to Reagan and Clinton, to rightwing and left. Particularly at the end of Clinton Administration we saw the most important reversal of the legislative heritage from the 1930s. From a political-economic angle how we can deal with this “anomaly”?

In his new book, James K. Galbraith synthesizes Veblen’s notion of the predator with John Kenneth Galbraith’s new industrial state. The result is what the younger Galbraith terms the predator state. He argues the “industrial state”—related to Minsky’s notion of paternalistic capitalism– has been replaced by a predator state, whose purpose is to empower a high plutocracy that operates in its own interests. I link the Veblen/Galbraith notion of predators to the take-over of the state apparatus in the interest of money managers by neoconservatives (or what are called neoliberals outside the US). I wrote a piece on the neoconservatives, available as:

Public Policy Briefs August 2005 The Ownership Society Public Policy Brief No. 82, 2005, www.levy.org

Yes, I do agree that monetary policy was guided by a “new monetary consensus” that combined elements of monetarism, the old ISLM approach of “bastard” Keynesians, and the so-called New Keynesian approach. It supposedly put policy in the hands of the central bank and downplayed fiscal policy. I wrote about that in a brief available as:

Public Policy Briefs December 2004 The Fed and the New Monetary Consensus Public Policy Brief No. 80, 2004, www.levy.org

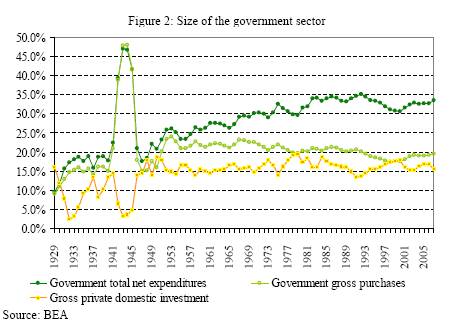

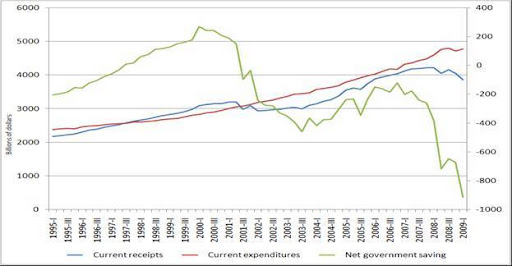

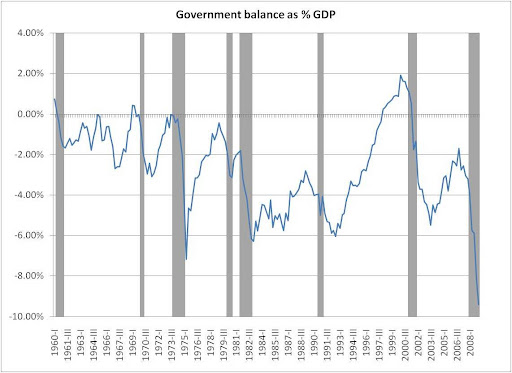

In reality, fiscal policy was still used, but in the interests of money managers. And now we know that the new monetary consensus policy never really worked. Monetary policy is in complete disarray.

3- Most of these “heroes” of the money manager capitalism, like Greenspan or Bernanke, thought that policies, particularly monetary manipulation and a growing rent-seeking system, can “moderate” the business or even the long cycles and that continuous growth was the perpetual horizon. This high qualified people has a weak memory from history?

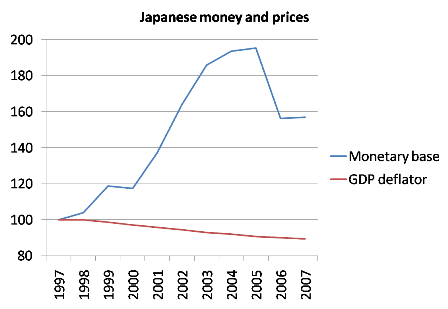

Obviously, it was purely fantasy: the belief that the central bank can fine-tune the economy merely by controlling expectations of inflation. The central bank cannot control expecations, and it cannot control inflation. And, as everyone now recognizes, monetary policy has very little impact on the economy. That is why we have turned to fiscal policy. See my piece:

Public Policy Briefs March 2009 The Return of Big Government: Policy Advice for President Obama Public Policy Brief No. 99, 2009, www.levy.org

4- Which was the “Minsky moment” that triggered the present crisis? Which fact will you choose in 2007 to mark the bust of this crisis?

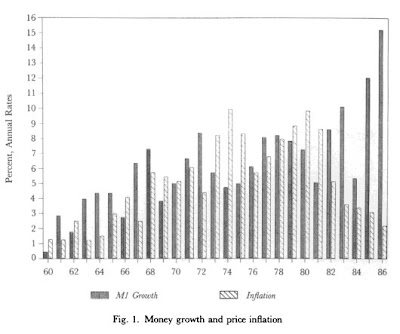

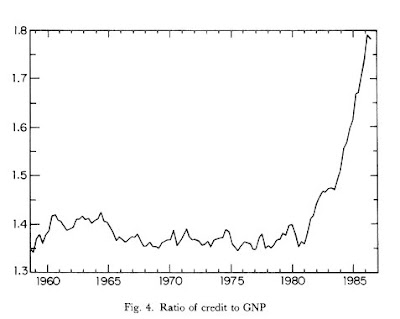

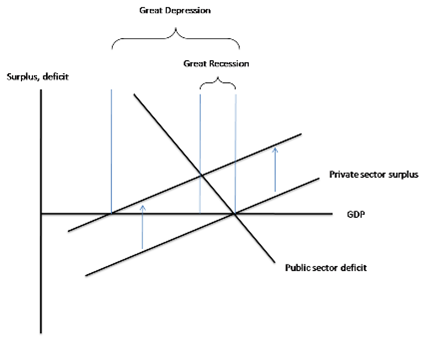

Hyman Minsky’s work has enjoyed unprecedented interest, with many calling this the “Minsky Moment” or “Minsky Crisis”. I am glad that Minsky is getting the recognition he deserves, but we should not view this as a “moment” that can be traced to recent developments. Rather, as Minsky had been arguing for nearly fifty years, what we have seen is a slow transformation of the financial system toward fragility. It is essential to recognize that we have had a long series of crises, and the trend has been toward more severe and more frequent crises: REITs in the early 1970s; LDC debt in the early 1980s; commercial real estate, junk bonds and the thrift crisis in the US (with banking crises in many other nations) in the 1980s; stock market crashes in 1987 and again in 2000 with the Dot-com bust; the Japanese meltdown from the early 1980s; LTCM, the Russian default and Asian debt crises in the late 1990s; and so on. Until the current crisis, each of these was resolved (some more painfully than others; one could argue that Japan never successfully resolved its crisis) with some combination of central bank or international institution (IMF, World Bank) intervention plus a fiscal rescue (often taking the form of US Treasury spending of last resort to prop up the US economy to maintain imports).

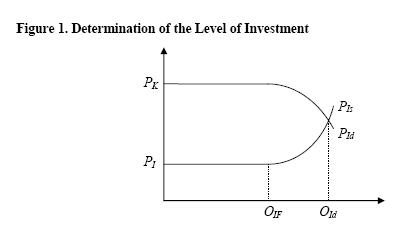

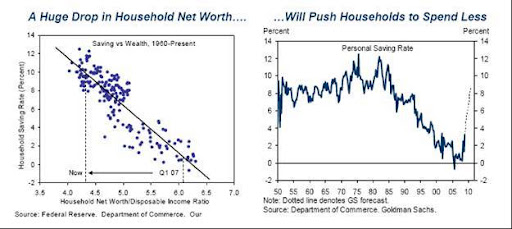

Minsky always insisted that there are two essential propositions of his “financial instability hypothesis”. The first is that there are two financing “regimes”—one that is consistent with stability and the other in which the economy is subject to instability. The second proposition is that “stability is destabilizing”, so that endogenous processes will tend to move a stable system toward fragility. While Minsky is best-known for his analysis of the crisis, he argued that the strongest force in a modern capitalist economy operates in the other direction—toward an unconstrained speculative boom. The current crisis is a natural outcome of these processes—an unsustainable explosion of real estate prices, mortgage debt and leveraged positions in collateralized securities in conjunction with a similarly unsustainable explosion of commodities prices. Unlike some popular explanations of the causes of the meltdown, Minsky would not blame “irrational exuberance” or “manias” or “bubbles”. Those who had been caught up in the boom behaved “rationally” at least according to the “model of the model” they had developed to guide their behavior.

Following Hyman Minsky, I blame money manager capitalism—the economic system characterized by highly leveraged funds seeking maximum returns in an environment that systematically under-prices risk. See my piece:

Public Policy Briefs April 2008 Financial Markets Meltdown Public Policy Brief No. 94, 2008, www.levy.org

With little regulation or supervision of financial institutions, money managers have concocted increasingly esoteric instruments that quickly spread around the world. Contrary to economic theory, markets generate perverse incentives for excess risk, punishing the timid. Those playing along are rewarded with high returns because highly leveraged funding drives up prices for the underlying assets—whether they are dot-com stocks, Las Vegas homes, or corn futures. Since each subsequent bust only wipes out a portion of the managed money, a new boom inevitably rises. However, this current crisis is probably so severe that it will not only destroy a considerable part of the managed money, but it has already thoroughly discredited the money managers. Right now, it seems unlikely that “business as usual” will return. Perhaps this will prove to be the end of this stage of capitalism—the money manager phase. Of course, it is too early to even speculate on the form capitalism will take.

5- Basle is obsolete?

Basle helped the money managers to create the conditions that led to collapse. I actually wrote in late 2005 that Basle II would generate financial fragility, and presented a paper in Brazil making that argument. It was published by the Levy Institute as:

Public Policy Briefs May 2006 Can Basel II Enhance Financial Stability? Public Policy Brief No. 84, 2006, www.levy.org

And it was also published in Portuguese in Brazil. Basle requirements operated on the belief that higher capital ratios would reduce risk; and further that greater market efficiency could be achieved by adjusting those ratios based on the riskiness of assets purchased. And, finally, it was believed that “markets” are best able to assess risk. In practice, larger institutions were allowed to asses the riskiness of their assets. We now know that failed completely—because all the incentive was for institutions to underestimate risks.

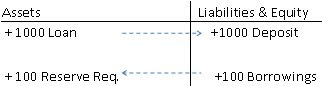

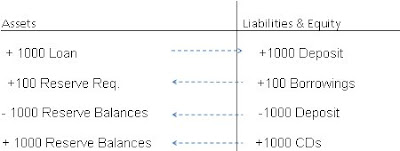

We must recognize, as Minsky did, that banking is a profit-seeking business that is based on very high leverage ratios. Further, banks serve an important public purpose and thus are rewarded with access to the lender of last resort and to government guarantees. What this means is that as soon as capital ratios decline toward some minimum (zero in the case of an institution subject only to market discipline, or some positive number set by government supervisors as the point at which they take-over the institution), management will “bet the bank” by seeking the maximum, risky, return permitted by supervisors. In any event, there is always an incentive to increase leverage ratios to improve return on equity. Given that banks can finance their positions in earning assets by issuing government-guaranteed liabilities, at a capital ratio of 5% for every $100 they gamble, only $5 is their own and $95 is the government’s. In the worst case, they lose $5 of their own money; but if their gamble wins, they keep all the profit. Imagine if you walked into a casino and the government gave you $95 to gamble with, for every $5 of your own—and you get to keep all the winnings. What would you do? Gamble! If subjected only to market forces, profit-seeking behavior would be subject to many, and frequently spectacular, bank failures. The odds are even more in their favor if government adopts a “too big to fail” strategy—although exactly how government chooses to rescue institutions will determine the value of that “put” to the bank’s owners.

Note that while the Basle agreements were supposed to increase capital requirements, the ratios were never high enough to make a real difference, and the insitutions were allowed to assess the riskiness of their assets for the purposes of calculating risk-adjusted capital ratios. If anything, the Basle agreements contributed to the financial fragility that resulted in the global collapse of the financial system. Effective capital requirement would have to be very much higher, and if they are risk-adjusted, the risk assessment must be done at arms-length by neutral parties. I think that if we are not going to closely regulate financial institutions, capital requirements need to be very high—maybe 100%. We used to have “double indemnity”: owners of banks were personally liable for twice as much as the bank lost. That, plus prison terms, would perhaps give the proper incentives.

6- Do you think we need a strict regulation of the financialisation of commodity markets (particularly oil) as Sarkozy, Gordon and the US regulator claimed, or this is a window for non-commercial investors that came to stay?

As implied above, any institution that has explicit or implicit government guarantees—either through deposit insurance or “too big to fail” policy absolutely must be closely regulated.

7- Do you think the sovereign wealth funds and the Asian banks from high liquidity countries (now the 3 top banks in capitalization are Chinese) will be dragged down by the crisis or they can lead a new financial capital wave?

No, I do not think they will lead a new financial wave over the next few years. There is little doubt that the Chinese economy will continue to become important and in the near future will displace the US economy as the largest in the world. It is certainly possible that its currency will eventually displace the dollar as the global reserve currency–but I think that is a long way off. I do not think it is even a role that the Chinese authorities would want right now. Finally, China uses markets where they work, but happily intervenes where markets do not fulfill the public purpose as defined by the government. Hence, I do not believe they would let their own domestic money managers “run wild” in the same way that the more market-oriented (neo-liberal) governments have done. After all, the Premier of China has no fear of being labeled a “socialist”–unlike President Obama!

Obviously, global financial losses are already huge, and will grow much larger over the coming years. Only the debt of sovereign nations is safe. Again, I hope, and expect, that we are seeing an end to this phase of finance capitalism. It will, of course, rise again—eventually. But with proper responses by governments around the world, we might be able to develop the conditions necessary for another “golden age”. Still, as Minsky said, stability is destabilizing so a golden age will allow finance capital to return. There is no “final solution” to the fundamental flaws of capitalism: an arbitrary and excessively unequal distribution of income and wealth, an inability to generate full employment, and a propensity toward financial instability.