By Dan Kervick

As you read this, millions of Americans who desperately want to work either cannot find employment at all, or cannot find the quantity and quality of work they need to meet their own needs and the needs of their families. This is real suffering. The unemployed are real flesh-and-blood people, not just fractions of percentage points on Labor Department spreadsheets.

At the same time, we have tremendous unmet social needs. Any well-informed high school student can point to large, daunting national challenges that we sorely need to address, but that we are not addressing with anything approaching the urgency and commitment that the gravity of the challenges would seem to demand of us.

So the availability of unemployed human labor power is extremely high, while the need for applied, energetic human effort is extremely acute.

Mainstream textbook economics tells us that these kinds of problems are supposed to solve themselves without the need for active government intervention. The availability of some resource, on the one side, and the need to acquire those resources, on the other, are supposed to meet and court each other in the market. The former comes dressed as supply, and the latter as demand. Supply and demand curves intersect and copulate, give birth to a price and – voila! – the market clears as the satisfied suppliers and demanders perform their happy jig of mutual gratification.

Clearly, things are not working out that way, or at least not with the alacrity that the textbook accounts would suggest and that moral decency would require. Here in the US, while those sterile supply and demand curves languish in the logical space of microeconomic theory, the sorry employment scene has settled down into a new normal of persistently high joblessness with no end in sight. Yet much of the national discussion of the problem of unemployment in the United States is bogged down in pedantic side-discussions, commingled with cantankerous ideological stubbornness. The political class addresses the employment crisis with lame half-measures or impotent shrugs on one side of the debate, and with malevolent snickering and scapegoating of the jobless on the other side. Where the politicians rise above their pattern of neglect to put forward actual policies, the solutions offered consist in part of schemes to bribe corporations and their lobbyists into hiring by greasing corporate palms with crony tax giveaways.

What seems to be missing in the debate is public consideration of the most obvious solution: A nation faced with both pressing unmet needs for work and a large pool of available unemployed workers, and that also possesses sovereign control over its own currency system, can take on the responsibility of organizing the needed work itself, and then set about directly hiring and training the workers to do that work.

We have so far been hindered from taking this obvious step by our fundamentalist ideological mania for free market solutions and private enterprise. This stubborn fixation on private markets and private money is a forlorn ancestral doctrine in America which seems strangely resistant even to the most obvious lessons taught by the catastrophic recent failures of the system of private sector finance. Many Americans are also afflicted by a pathological hatred of the very government of which they themselves are supposed to be the sovereign masters.

And where archaic doctrine doesn’t prevail alone, powerful vested interests pick up the slack. Throughout the developed world corporate plutocrats and privileged stakeholders in a failing neoliberal order are working overtime to incapacitate democratic governments, starve them with austerity, and seize political control of their desiccated remains. There is a war going on everywhere between the corporate form of organization based on authoritarian control and elite hierarchy and the democratic form of organization based on shared power, empowered citizenship and the cooperation of equals. Right now, the corporations and plutocrats are winning.

The result is systemic failure by democratic societies to grasp and accept their historic responsibilities for active self-governance and bold self-determination. The notion that the private sector mechanisms of free market capitalism are sufficient to meet the emergencies of our time, and to organize and provide all of the work that needs to be done by and for our societies, doesn’t meet the test of either common sense or historical experience. The failing neoliberal world system is beyond wrong: it is a stupid, backward and barbaric system, and the countries who continue practice it inflict needless losses and suffering on their own citizens.

So it is time to move on and move forward. We need to revive and renew the public sector, embrace the necessary role of democratic government in setting and achieving large social tasks that the private sector is simply not equipped to handle, and liberate the army of the increasingly desperate unemployed from their indentured dependency on the whims of a dysfunctional and incomplete market system. It is time for the citizens of the world’s democratic countries to make full employment an axiomatic social goal, and to commit the public sectors of their respective countries to the task of providing the work that the private sector cannot or will not provide.

Let’s be clear about one thing: Unemployment on the scale we are seeing right now, both in the United States and around the world, is a moral catastrophe. The human costs of unemployment have been well documented by Bill Mitchell and his colleagues at CofFEE, the Center of Full Employment and Equity at the University of Newcastle in Australia. The unemployed often experience feelings of worthlessness and incompetence, and suffer higher rates of depression and suicide. They can lose their sense of connection and engagement with the broader society, and their alienation can become self-perpetuating. Their marketable skills atrophy and are lost as the economy moves forward without them. Marriages and family relationships are strained by unemployment, sometimes to the breaking point. Some of the persistently unemployed will turn to crime, and to other forms of self-destructive and anti-social activity. And in any society that values and promotes hard work, unemployment is simply humiliating, consigning the unemployed person to the lower caste status occupied by the jobless and the needy. In a word, unemployment sucks.

The problem of unemployment for the jobless individual is thus not solely due to a loss of income, although the loss of income is certainly at the root of many of the problems. In every thriving society, a tacit bond exists among the members of the society, a bond that is based on norms of reciprocity and mutual obligation. Each person receives substantial benefits by virtue of their membership in the society, and in return they are made to understand from an early age that they are expected to contribute their fair share of the work burden that is required for the society to prosper. Most people grasp and internalize these norms, and earnestly seek an opportunity to earn their way in the society and prove their value to their fellow citizens through their work. People want to be full and equal adult participants in their societies, not dependents on the charity of others. So when we deprive people of the opportunity to participate in the work force, and to put their best talents and skills to work for the good of themselves, their families and their societies, we rob them of an opportunity to manifest their dignity to others, and we steal their self-respect in the process.

But unemployment is not just a personal problem for the unemployed individual; it is also an economic problem for the larger society. When there is significant work to be done, mass unemployment represents a tremendous opportunity cost. It means that the society is failing to invest all they should in their current prosperity, and in the world they are going to leave to their descendants. We should therefore regard full employment as both a moral and economic imperative.

But a number of arguments have been put forward against a public commitment to a full employment economy. I want to respond briefly to the ones that seem most common.

One popular line of argument that we hear frequently from free market partisans asserts that the reason that there is so much unemployment these days is because there really isn’t all that much valuable work to be done. If there were valuable work to be done, the argument goes, the private sector would already be doing it. The private sector will find it profitable to hire people to do work so long as the marginal costs of hiring the additional workers falls below the marginal addition of value that would be created by doing the work. Since private businesses are not hiring, there must not be all that much potential value to be produced. Thus any public program of full employment is destined to be an economically wasteful misallocation of resources, a regime of pointless ditch-digging with the cost of administering the work effort exceeding the benefits of doing the work.

I can only say in response to these critics, “What world are they living in?” Let’s briefly consider some of the things that need to be done, and remind ourselves of the obvious reasons why the private sector isn’t already doing them all, and will never be able to do them all.

Private sector capital development occurs when some private person or enterprise takes some stuff they already own as inputs, does some work on those inputs, and transforms those inputs into outputs whose combined market value is greater than the combined value of the original inputs. They are willing to do the work in the first place because the estimated addition of value that results from the work is significantly greater than the estimated costs of the work itself. And since private enterprise exists to provide goods and services for exchange in markets, the added value that is produced must be marketable. Obviously, private individuals and enterprises won’t and can’t do the work on inputs that they do not own. And they obviously do not organize themselves for the production of intangible goods that cannot be bought and sold at a profit.

But just as obviously, there are vast resources in this world that no private sector entity either already owns, or can practically acquire through trade. Thus no private sector business will undertake capital development with those resources, even if there is great, untapped potential value to be created from those resources. And similarly, no private sector entity will undertake the expensive task of preserving valuable resources that already exist, if those resources don’t belong to them.

Large amounts of land and structures in this country are public property. Thus if we citizens want to add value to them through work, or simply maintain and preserve them in the face of threats, the public sector will have to organize and finance that work. Private capitalists do not own the air we breathe, and the water we drink. Not yet, at least. And nobody owns our people. Not yet, at least.

Another reason that the private sector cannot organize all of the work that needs to be done is that, even where improvable resources lie in private hands, those hands might be too scattered, too disorganized and too many to combine their resources effectively and do the work needed to realize the maximum potential of their resources. It might also be the case that no private individual or firm can consolidate the financing necessary to accomplish the task of realizing that potential. Only the combined power of the whole citizenry, deploying the latent powers that they have vested in their government to command and direct resources, can accomplish tasks that exceed a certain size. This was noted long ago my Adam Smith, who said governments must take on those tasks which “though they may be in the highest degree advantageous to a great society, are, however, of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals.”

Let’s start with investing in our people: The development of our fellow citizens can pay vast economic benefits. I’m not just talking about intangible cultural and social benefits, public goods of the kind markets do not measure and trade, and upon which markets do not place prices – although those benefits also will be very substantial indeed. I’m talking about economic benefits of very concrete kinds. If we deepen the pool of mathematical, scientific, imaginative and other intellectual talents, that will pay concrete economic benefits. If we work to make our people physically stronger and healthier, that also pays concrete economic benefits. These are the kinds of essential investments that only the public can undertake.

Private sector companies will ever do this human development work in sufficient amounts to realize the vast store of potential value that comes from doing that work. That’s because when a private company develops an individual human being’s capacities – which is an expensive process – they don’t own the human being that results, and they recover only a small portion of the overall value that is created. Thus it will never be in their interest to do much beyond the development of rudimentary job skills that pay off for them in the short or immediate term. It is up to the rest of us to develop our people for the long term. But due to the habits of an increasingly outdated cultural tradition, this is an investment task that we mainly restrict to the education of young people, after which the adults that result are left to fend for themselves. This approach no longer makes sense in an innovative, information-driven economy calling for ever-evolving intellectual skills.

So investing in our people is one vital area calling out for work. But there are others: Fewer and fewer people these days are able to ignore the fact that we are literally destroying our world, and that the global habitats and environment on which we and all other living things on Earth depend are facing acute threats. In my state of New Hampshire, for example, the average wintertime temperature has climbed over the past 40 years by over four and a half degrees, and we are experiencing another disturbingly mild winter this year. USDA scientists have recently noted that planting zones in North America are shifting northward. Ice caps are melting; water levels are rising; and the voices of the denialists are growing less strident.

I posit that saving ourselves from this gathering, man-made disaster is every bit as important for the present generation as saving the world from the man-made disaster of fascism was for the generation of the 1930’s and 1940’s. And yet, the private sector cannot wage and win the global war on environmental destruction. The needed investments are too enormous; the scale is too vast. Only the mobilized efforts of democratic political communities and their governments are up to the task.

During the period 1939 to 1945, in the course of waging a global war against fascism on every continent, the US economy doubled in size, and developed the human skills and material infrastructure that laid the foundation for decades of subsequent prosperity. And yet at no other time in our history did our government play a more active and engaged role. This fact is extremely embarrassing to the defenders of laissez faire and the haters of government. But it is a historical fact. If we wage a new global war, starting where we can in our own country, to save ourselves and our posterity from the rapid and ongoing destruction of our environment, and from our dependency on outdated, scarce and unhealthy energy resources, not only will we achieve something of inestimable value in itself, but we will also find that the investments we undertake in people, systems and equipment in order to achieve our lofty goals will generate enormous additional benefits.

Another argument we sometimes hear in opposition to a full employment economy is that although there is admittedly much valuable work to be done, we simply cannot afford to do it. Hiring people and paying them to work costs money. And we are told that we are “broke” and “out of money”.

This line of argument is profoundly misguided.

Money is a human technology. It is a tool created and managed by human beings to organize the tasks of assigning prices and values to goods and services, and to organizing the production, exchange and distribution of those goods and services. A sovereign government like the United States is not the mere user of a form of currency for whose existence it is dependent on someone else. The United States can always produce and issue the additional monetary resources and financial instruments it needs, in whatever quantities it needs, and it can do so at negligible cost. In the world of modern money, a sovereign currency issuer can create money simply by using computers to mark up the government accounts it administers. It is always possible that such a country cannot achieve some desired end because of a shortage or real, non-monetary resources. But it can never be the case that the government of such a country is incapable of organizing some needed effort of production and exchange because it has “run out” of the money over which that government itself exercises sovereign monopoly control. That’s like saying that we can’t have any more people in the world because we have run out of names.

These reflections lead, though, to an additional line of argument against a full employment economy. Even if it is granted that a monetarily sovereign government can never literally be “out of money”, it might still be the case that the government cannot create more money without generating inflation: that is, without sparking an unacceptable rise in the price level.

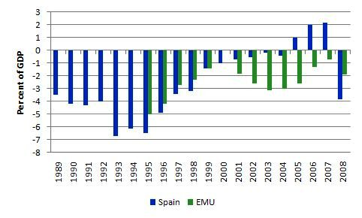

There are three points to make in response to this argument. First, increases in the supply of money are supposed to lead to higher prices because the additional money enters the market to bid for a supply of goods and services whose quantity is not increasing at the same pace as the supply of money. And it is no doubt true that when an economy is running at full capacity, its total output of goods and services cannot increase rapidly. But our economy in the United States is not at full capacity. We are nowhere near it. Nor are the economies of Europe at full capacity. Over 50% of Spanish youth between the ages of 16 and 24 are unemployed! In Portugal, Greece and Italy, the unemployment numbers are almost equally ghastly. Additional government spending and hiring in all of our countries will indeed raise incomes and the demand for goods and services. But the production of marketable goods and services will ramp up rapidly as well. We will not face severe inflation as a result.

Second, not every one-time rise in prices is a social burden. Suppose the government goes into the business of producing new goods and services that are not intended for sale in the market, but are delivered directly to the end users as “free” public goods and public services. Then it is true that the injection of monetary income might bid up prices on the existing goods and services that are produced for markets. But in return the public has received a valuable new supply of public goods, and the higher prices on ordinary consumer goods can be considered a kind of tax that pays for the public goods and services. If we have to pay a little bit more for yogurt and iPhones, it will be worth the increase if we receive outstanding public education and infrastructure improvements in return. Also, it is important to remember that an increase in nominal prices, so long as it is matched by a corresponding increase in nominal wages, helps debtors pay down their debt burdens faster.

Finally, if worries about unacceptable upward pressures on prices become too acute, we can always rely on additional taxation to dampen excess demand. It is true that in a recessionary economy it is best to avoid additional taxes. But if vital public needs require significant new outlays of public spending, and if we become convinced we must drain some purchasing power from some parts of the economy to stabilize prices, we can tap into the surplus wealth of the most fortunate members of our society to drain off some of that purchasing power.

This brings us to another argument against a full employment economy. It is often held that a national commitment to full employment, financed by the government, will increase labor costs. My response to this complaint is simple: We should only be so lucky! Working Americans have endured 20 years of stagnant real wages while the rewards granted to the most fortunate members of our society have rocketed upward. The ratio of CEO pay to average worker pay in the US is now well up in the hundreds, while in other prosperous countries like Japan and Sweden it stands at 11-to-1 or 12-to-1. Persistent unemployment provides the management of American corporations with a permanent buyers’ market for labor, which helps them drive down labor costs so they can afford to pay themselves more. If America’s workers get improved bargaining power, if they have increased work options because of the opening of opportunities in the public sector, and if employers have to compete more aggressively for their services, then competitive international pressures will force corporate management to pay themselves less so they can pay their workers more.

Of course the plutocracy has other ideas. They have a neo-feudalist strategy to drive labor costs down even further, so that their beggared workers can then “compete” with the Chinese and other serfs. Yet one notes that the people making these proposals are not offering to slash their own salaries and earnings in order to make themselves more “competitive” with management in other countries. They are instead doing everything they can to hold onto what they have.

So the complacent intuition that unemployment is an unfortunate by-product of a world in which we have either run out of work to be done or run out of the money to do it is far, far off the mark. And the arguments against a full employment economy are unavailing. There is tremendous untapped potential to be realized. Our civilization is grossly underperforming, and even destroying itself, because of our stubbornly misguided and ideologically blinkered over-reliance on private sector self-sufficiency and self-correction. We will always need a vigorous, innovative and creative private sector. But right now, what we need even more is a renewed public sector, animated by public spirit and determined to live up to its unique obligations and opportunities. It’s time for us to take charge of our governments again, and use their latent powers to do the things that need to be done.