In theory, this rally in bond yields should lead to a reassessment of thegravity of the Italian problem and therefore the European sovereign debt andbanking problem. That could be positive for equity markets and, indeed, hasbeen so since the start of the year.

But does Spain truly deserve theborrowing advantage it now has in relation to Italy? Its 10-year bonds are yielding some 60 basispoints lower. True, its sovereign debt to GDP ratio is low at about 75%, but partof its enormous private debt will almost certainly have to be “socialized.” Moreover, Spain has virtually the highestnon-financial private debt-to-GDP ratio of all the major economies. Its ratio is almost twice that of Italy’s. Itsfiscal deficit last year was probably higher than the official estimates, closeto 9% of GDP (the previous Socialist government routinely lied about itsfigures – in fact, no country, not even the US, has lied more extensively aboutthe condition of its banks. Spain, relative to GDP, has the largestshadow real estate inventory in the world, with the possible exception ofChina, which probably doesn’t even have a reliable second or third set ofbooks).

Let’s be clear about onething: this is not a tale of Mediterranean“profligacy”, as least as far as public spending was concerned. Anybody looking at Spain through a sensiblefinancial balances framework in the mid-2000s would have observed that theprivate sector was being squeezed badly by the fiscal drag. The externalposition was in deficit (current account) which means the public and externalbalances were draining growth from the economy. Yet it still boomed up into theonset of the crisis. How did that happen?

The profligates were all in theprivate sector, although you could readily argue that the government’s“responsible” fiscal policy created the conditions for a private sector debtbinge. Prior to 2008, the Spanisheconomy was held out as the darling of Europe however the reality was quitedifferent. The country was running budget surpluses by 2005 and foreigninvestment was booming. Most of this investment went into construction whichwas stimulated by a massive real estate boom.

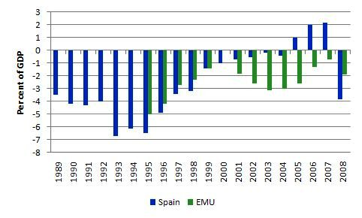

A few years ago, using data fromData from the Banco de España (central bank) Bill Mitchell graphed the nationalbudget deficit as a percentage of GDP for Spain and the EMU overall from 1989to 2008 (data for the EMU clearly didn’t start until 1995). As Mitchell notes,one can observe the tightening of fiscal positions as the Growth and StabilityPact provisions were forced on the EMU nations:

Consistent with a tighteningfiscal position leading to surpluses in 2005, the only way that this boom couldcontinue was for the private sector to go increasingly into debt.That is exactly what happened and because the property boom was so large thedebt levels were also very high – average household debt tripled. And that, incontrast to Italy, is the core problem with which Spain is dealing today to asubstantially greater degree than Italy. So it’s wrong to lump the two together interchangeably as the marketshave been doing. Paella and pasta don’tmix well together.

Okay, but that was the previousZapatero Administration. Now we supposedly have a new “responsible” conservativegovernment that promises to carry out the same policies even moreresolutely. And look how successfulthey’ve been: Spain’s joblessclaims shot up a further 4% in January from December to 4.59 million, a signthat the euro zone’s fourth-largest economy is still shedding jobs at a recordrate. All sectors posted more claims but the rise was sharpest for services at5.1%. In construction, weighed down by a four-year property slump, the numberof residents registered as job seekers rose 2.1%. Compared with the same perioda year ago, overall claims rose 8%. GDPcontracted 0.3%.

Okay,“give them time”, argue the defenders of the new government. And, if the Rajoy Administration was trulyembarking on a new policy course, that would be a fair comment. Unfortunately, this government has signed onto even tighter fiscal policy rules. Somehowthey are expected to suck demand out of their economies through tax increasesand spending cuts, but when the slower growth that results in means the targetfor deficit reduction is not met, the Spanish, like their Greek, Irish,Portuguese and Italian counterparts, will be punished for it.

Eventhe Rajoy Administration implicitly appears to recognize this danger, as it isalready moving the goalposts in regard to its spending cuts targets as apercentage of GDP. Unfortunately, theyblame this on external circumstances beyond their control. To the extent thatthey agree to submit themselves to rules which were routinely disobeyed by theGermans and French during the EMU’s inception, that is true, although theSpanish government refuses to acknowledge that their resolute tightening fiscalpolicy ex ante might well have something to do with the fact that Spain’seconomy continues to deflate into the ground ex post. Remember, thehistory of the Stability and Growth Pact has long demonstrated that thesenonsensical rules are already impossible to keep within during a significantdownturn. And now the new Spanish government wants to tighten them even furtherand invoke pro-cyclical fiscal reactions earlier.

This, at a time when the nationalunemployment rate is approaching 23%, and the youth unemployment rate (25 yearsor younger) is at 49%, according to the latest Eurostat data.

Sonearly 50 per cent of willing workers under the age of 25 in Spain are withoutwork and will remain like that for years to come. That will damage productivitygrowth for the next decade or more. It is an indication that the monetarysystem has failed and attempting to reinforce those failures with moreausterity will only make matters worse. The new government’s proposed fiscal policy “reforms” areparticularly toxic policy mixture for Spain.

Of course, the ongoing threat ofa disorderly default in Greece also remains a potentially dangerous areaif it is not contained by the ECB’s actions. But it’s more interesting to see what happens as the magnitude ofSpain’s problems become more apparent. Will the troika tell Spain that a Greek style70% haircut is not in the cards? Willthey try to suggest that the government is rife with corruption, that thecountry is chock-a-block full of scoff-laws and tax evaders, and that theefficient Germans would do a much better job of collecting taxes?

Spain is still a relatively youngdemocracy. The transition began a mere37 years ago when Francisco Franco died in 1975, but there was an attemptedcoup by Antonio Tejero as recently as 1981. This is worth pondering whilst observing the implosion of Spain’seconomy. The decision for Europe’s bosses is this: they must ultimately confront theconsequences of their policy choices. They can destroy the eurozone by continuing with the same failed mix ofpolicies or by salvaging it by adding what has been missing from the outset: amechanism for shifting surpluses to the deficit regions in the form ofproductive investments(as opposed to handouts or loans). Turning stateslike Spain into sundrenched economic wastelands within the eurozone, andforcing the rest of the currency area into a debt-deflationary spiral, is amost efficient way of blowing up the whole system and possibly threatening thevery existence of Spanish liberal democracy itself.