In his book,

Leakages, Treval Powers makes the outrageous claim that without leakages, the US economy could grow at a sustained rate of 13% annually. According to his calculations (based on empirical evidence), normal leakages of 7.4% reduce the rate of growth to 5.6%, leaving the economy operating at only 92.6% of its capacity. Periodic restrictive policy by the Federal Reserve adds another layer of leakages, which can reduce growth to zero, causing the economy to operate at only 87% of potential.

Ironically, the Fed imposes tight policy because it wrongly believes that inflationary pressures result from excessive demand, even though the economy chronically operates well below capacity. Indeed, Powers argues that the greater the leakages, the higher the price level, hence, when the Fed tightens it actually puts upward pressure on prices. In his view, the economy has not been supply constrained, at least in the postwar era, so there has been no reason to fight inflation by constraining demand.

All of this goes against the conventional wisdom. Powers might be dismissed as a crank, as someone who simply does not understand economics. While I do find most of his analysis of monetary policy somewhat confusing, I agree with the general conclusions. What I will do in this note is to concur on two main points:

1. the US economy suffers from chronic inadequate demand, and has rarely been subject to any significant supply constraints—whether of productive capacity or of labor;

2. and leakages have been the cause of the demand constraints

Thus, I also agree with the policy conclusions of Powers: Fed policy can be seen as a string of mistakes guided by a fundamentally flawed view that causes the Fed to tighten policy exactly when it should be loosened. Inflation in the US does not result from excessive aggregate demand and, indeed, our worst bouts with inflation have come during periods of above-normal slack.

However, I do not believe that Fed policy normally has a huge impact on the economy, and for that we should be eternally grateful given how misguided it has been. This is the major disagreement I would have with Powers and other critics of the Fed. I could go even further and argue that we really do not know whether restrictive policy by the Fed actually reduces aggregate demand—and whether lower interest rates stimulate demand—but that would take us too far afield.

Fiscal policy is the primary way in which government impacts the economy, and, unfortunately, it has become increasingly misguided in ways that many do not understand—especially during the Bush dynasty era in which populists, leftists, and the Democratic party have wrongly advocated a return to what they call fiscal responsibility. Thus, rather than focusing on monetary policy failings as the cause of demand slack, I highlight the role played by fiscal policy.

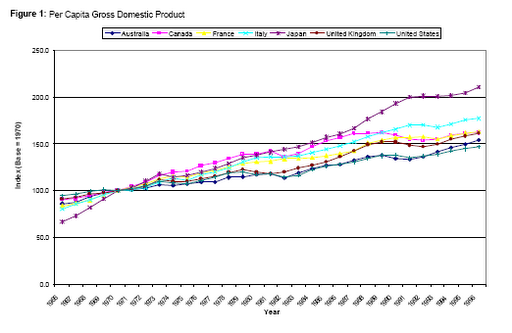

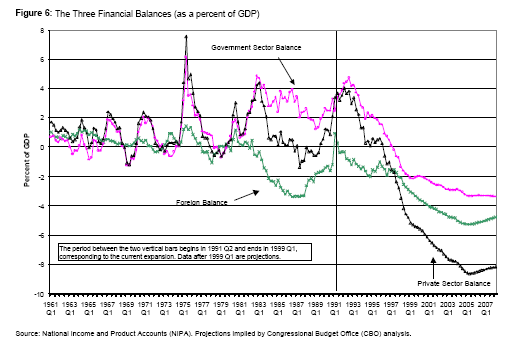

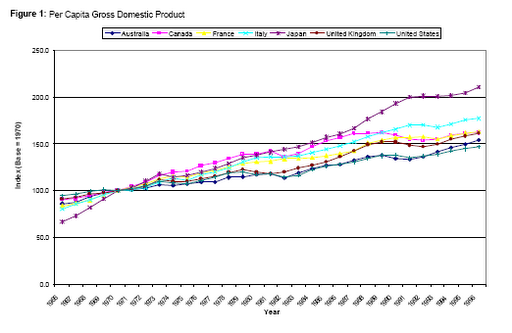

Let me begin with my argument that the US economy, as well as the economies of all the other major nations, have suffered from demand constrained growth. Figure 1 compares the per capita inflation-adjusted GDP growth of the major developed nations—indexed to 100 in 1970. Note the relatively rapid growth of Japan.

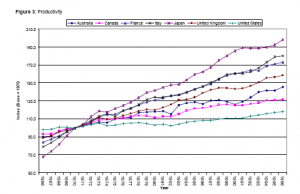

Per capita (inflation adjusted) GDP growth can be attributed by identity to growth of the employment rate (workers divided by population) plus growth of productivity per worker. Figure 2 shows employment rate growth by nation. Note that only the US and Canada had much growth of the employment rate. The long term trend in these two countries is rising as more women come into the labor force. There are also obvious cyclical trends—especially in Canada—when employment rates can actually fall off due to unemployment. Employment rates actually fell in France on a long-term trend, while they were more or less stable in the other nations.

I attribute the low growth of employment rates to slow growth of aggregate demand; that is, if aggregate demand does not grow at a clip sufficiently above productivity growth, then employment rate growth must (identically) suffer. Indeed, growth in Japan and Europe has not been high enough to increase employment rates—so they have come up with all these schemes to increase vacations, lower retirement ages, and share work (France’s experiment with mandated work week reductions is the most glaring example).

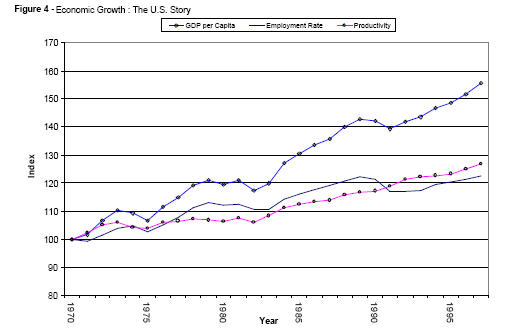

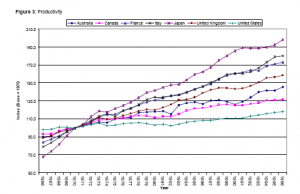

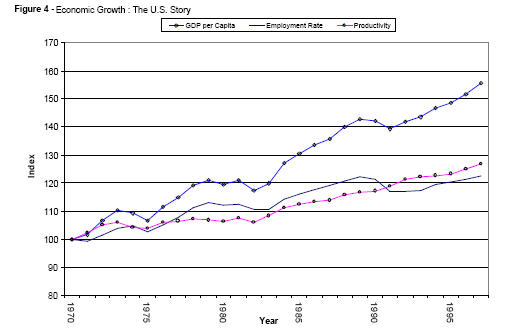

Figure 3 shows productivity growth. Recall that the sum of growth of the employment rate plus growth of productivity equals total per capita GDP growth. Japan, Italy and France had the best productivity growth—these are all nations that had no employment growth. Note that the US is at the bottom here. In the US our employment rate grows fairly strongly (for a number of reasons: population growth, immigration, and women entering the labor force) but given low growth of GDP, our productivity suffers. Figure 4 shows that our growth is just about evenly divided between employment growth and productivity growth.

These two figures shed light on a three-decades long controversy over productivity growth in the US. All during the 1970s and 1980s there was this hysteria about low productivity growth that was supposed to be the cause of low GDP growth. This is a supply side argument and led to all the policy measures, like tax cuts for the rich and other schemes to raise saving, to try to stimulate productivity through induced investment. In fact, the low productivity falls out of an identity; if the US grows at only 3% and if our employment rate grows at 2% it is mathematically impossible for productivity to grow at anything other than 1%.

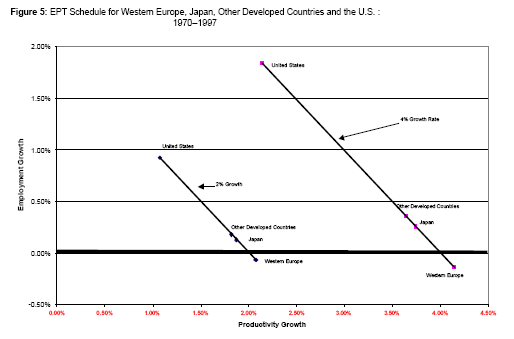

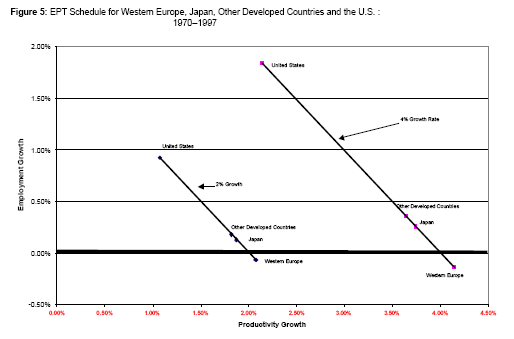

Figure 5 shows a hypothetical trade-off for the US, Europe and Japan. In other words, for the US to have productivity growth as high as that of Japan or Europe—or as high as we had during the so-called new economy boom under Clinton–we must grow above 4 or 5% per year. This is something we rarely achieve for very long—for reasons I’ll get to in a second. During the Clinton boom there was all this nonsense about information technology that had suddenly made it possible to grow at such rates precisely because productivity was supposed to be able to grow fast. In reality, the fast growth of the Clinton years could have been achieved at any time, if only demand had been that robust.

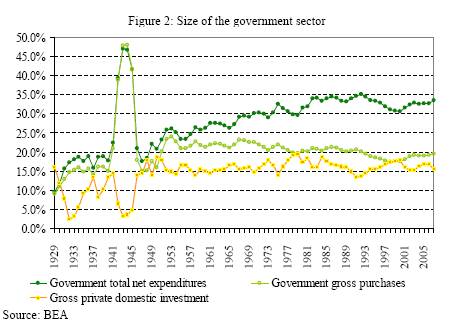

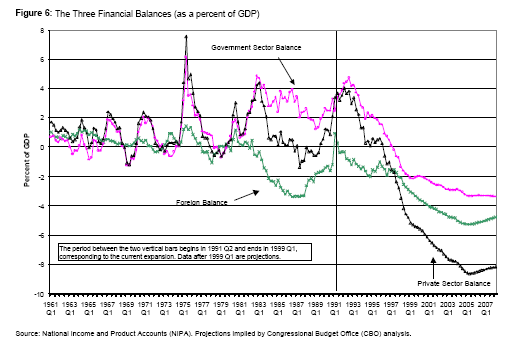

That brings me to my second main point—the leakages that constrain demand, resulting in chronic underperformance. We can think of the economy as being composed of 3 sectors: a domestic private sector, a government sector, and a foreign sector. If one of these spends more than its income, at least one of the others must spend less than its income because for the economy as a whole, total spending must equal total receipts or income. So while there is no reason why any one sector has to run a balanced budget, the system as a whole must. In practice, the private sector traditionally runs a surplus—spending less than its income. This is how it accumulates net financial wealth. For the US this has averaged about 2-3% of GDP, but it does vary considerably over the cycle. That is a leakage that must be matched by an injection.

Before Reagan we essentially had a balanced foreign sector—we ran trade surpluses or deficits, but they were small. After Reagan, we ran growing trade deficits, so that today they run about 5% of GDP. That is another leakage.

Finally, our government sector taken as a whole almost always runs a budget deficit. This has reached to around 5% under Reagan and both Bushes. That is the injection that offsets the private and foreign sector leakages. With a traditional private sector surplus of 3% and a more or less balanced trade account, the “normal” budget deficit needed to be about 3% during the early Reagan years. In robust expansions, before the Clinton years, the domestic private sector occasionally ran small and short lived deficits—an injection that allowed a trade deficit to open up, and reduced the government budget deficit. See Figure 6.

Until the Clinton expansion, the private deficits never exceeded about 1% of GDP and never lasted more than 18 months. However, since 1996 the private sector has been in deficit every year, and that deficit climbed to more than 6% of GDP at the peak of the boom. This actually drove the budget into surplus of about 2.5% of GDP. With the trade deficit at about 4% of GDP, the private sector deficit was the sum of those—almost 6.5%. While everyone thought the Clinton budget surplus was a great achievement, they never realized that by identity it meant that the private sector had to spend more than its income, so that rather than accumulating financial wealth it was running up debt.

Let me link this back to the leakages discussed by Powers. The trade deficit represents a leakage of demand from the US economy to foreign production. There is nothing necessarily bad about this, so long as we have another source of demand for US output, such as a federal budget that is biased to run an equal and offsetting deficit. Private sector net saving (that is, running a surplus) is also a leakage. As discussed above, that was typically 2-3% in the past. If we add in the trade deficit that we have today (5% of GDP), that gives us a total “normal” leakage out of aggregate demand of 7 or 8%–about equal to the estimates of Powers.

This leakage has to be made up by an injection from the third sector, the government. The only way to sustain a leakage of 7-8% is for the overall government to run a deficit of that size. Since state and local governments have to balance their budgets, and on average actually run surpluses, it is up to the federal government to run deficits. The federal budget deficit is largely non-discretionary over a business cycle, and at least over the shorter run we can take the trade balance as also outside the scope of policy.

The driving force of the cycle, then, is the private sector leakages. When the private sector has a strong desire to save, it tries to reduce its spending below its income. Domestic firms cut production, and imports might fall too. The economy cycles downward into a recession as demand falls and unemployment rises. Tax revenues fall and some kinds of social spending (such as unemployment compensation) rise. The budget deficit increases more-or-less automatically. That is where we are today, with Bush budget deficits rising to 5% of GDP and, soon, beyond. They will probably need to reach 8% before we get a sustained recovery.

In sum, we experienced something highly unusual during the Clinton expansion because the private sector was willing to spend far more than its income; the normal private sector leakages turned into very large injections. The economy grew quickly and tax revenues literally exploded. State governments and the federal government experienced record surpluses. These surpluses represented a leakage that brought the expansion to a relatively sudden halt. What we have now is a federal budget that is biased to run surpluses except when growth is very far below potential. This means is that the “normal” private sector balance now must be a large deficit in order for the economy to grow robustly.

Rather than the government sector being a source of injections that allow the leakages that represent private sector savings, we now have the private sector dissaving in order to allow the foreign and government sector leakages. This sets up a highly unstable situation because private debt ratios rise quickly and a greater percentage of income goes to service those debts. While I said at the beginning that Fed policy normally doesn’t matter much, in a highly indebted economy, rising interest rates can increase debt problems very quickly—setting off bankruptcies that can snowball into a 1930s-style debt deflation. A far more sensible policy would be to reverse course and lower interest rates, then keep them low.

At the same time, the federal government should take advantage of slack demand and abundant labor by increasing its spending on domestic programs. Robust economic growth fueled by federal deficits is the best way to reduce over-indebtedness. It is hard to say what to do (if anything) about euphoric stock or real estate markets that could be stoked by renewed growth. But the Fed’s sledgehammer approach of jacking up interest rates does not work. We will probably need selective credit controls to constrain financial speculation, if such is desired.

In conclusion, I agree with Powers that growth in the postwar period has mostly been demand constrained, due to leakages. If demand were to grow at 7% or even 10% on a sustained basis, I see no reason to believe that supply could not keep pace. This is all the more true in today’s global economy with massive quantities of underutilized resources all over the world, and with the rest of the world desires to accumulate dollar-denominated financial assets. This requires that they sell output to the US—which is just the counterpart to our trade deficit leakage. In real terms, a trade deficit means we can enjoy higher living standards without placing pressure on our own nation’s productive capacity. While it is hard to project maximum sustainable growth rates, there can be little doubt that our economy chronically operates far below feasible rates. The best policy would be to push up demand, allow growth rates to rise, and try to test those frontiers.

Reference:

Treval C. Powers, Leakage: The bleeding of the American economy, Benchmark Publications, Inc, New Canaan, Connecticut, 1996.