By Michael Hudson

Most of the press has described Europe’s labor demonstrations and strikes on Wednesday in terms of the familiar exercise by transport employees irritating travelers with work slowdowns, and large throngs letting off steam by setting fires. But the story goes much deeper than merely a reaction against unemployment and economic recession. At issue are proposals to drastically change the laws and structure of how European society will function for the next generation. If the anti-labor forces succeed, they will break up Europe, destroy the internal market, and render that continent a backwater. This is how serious the financial coup d’etat has become. And it is going to get much worse – quickly. As John Monks, head of the European Trade Union Confederation, put it: “This is the start of the fight, not the end.”

Spain has received most of the attention, thanks to its ten-million strong turnout – reportedly half the entire labor force. Holding its first general strike since 2002, Spanish labor protested against its socialist government using the bank crisis (stemming from bad real estate loans and negative mortgage equity, not high labor costs) as an opportunity to change the laws to enable companies and government bodies to fire workers at will, and to scale back their pensions and public social spending in order to pay the banks more. Portugal is doing the same, and it looks like Ireland will follow suit – all this in the countries whose banks have been the most irresponsible lenders. The bankers are demanding that they rebuild their loan reserves at labor’s expense, just as in President Obama’s program here in the United States but without the sanctimonious pretenses.

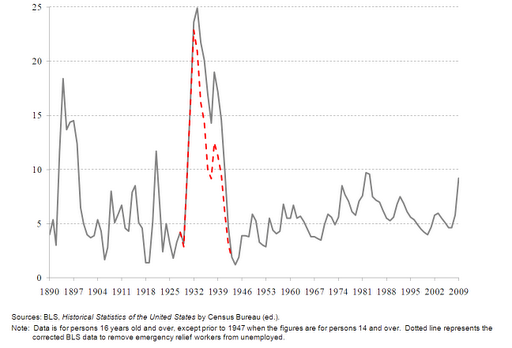

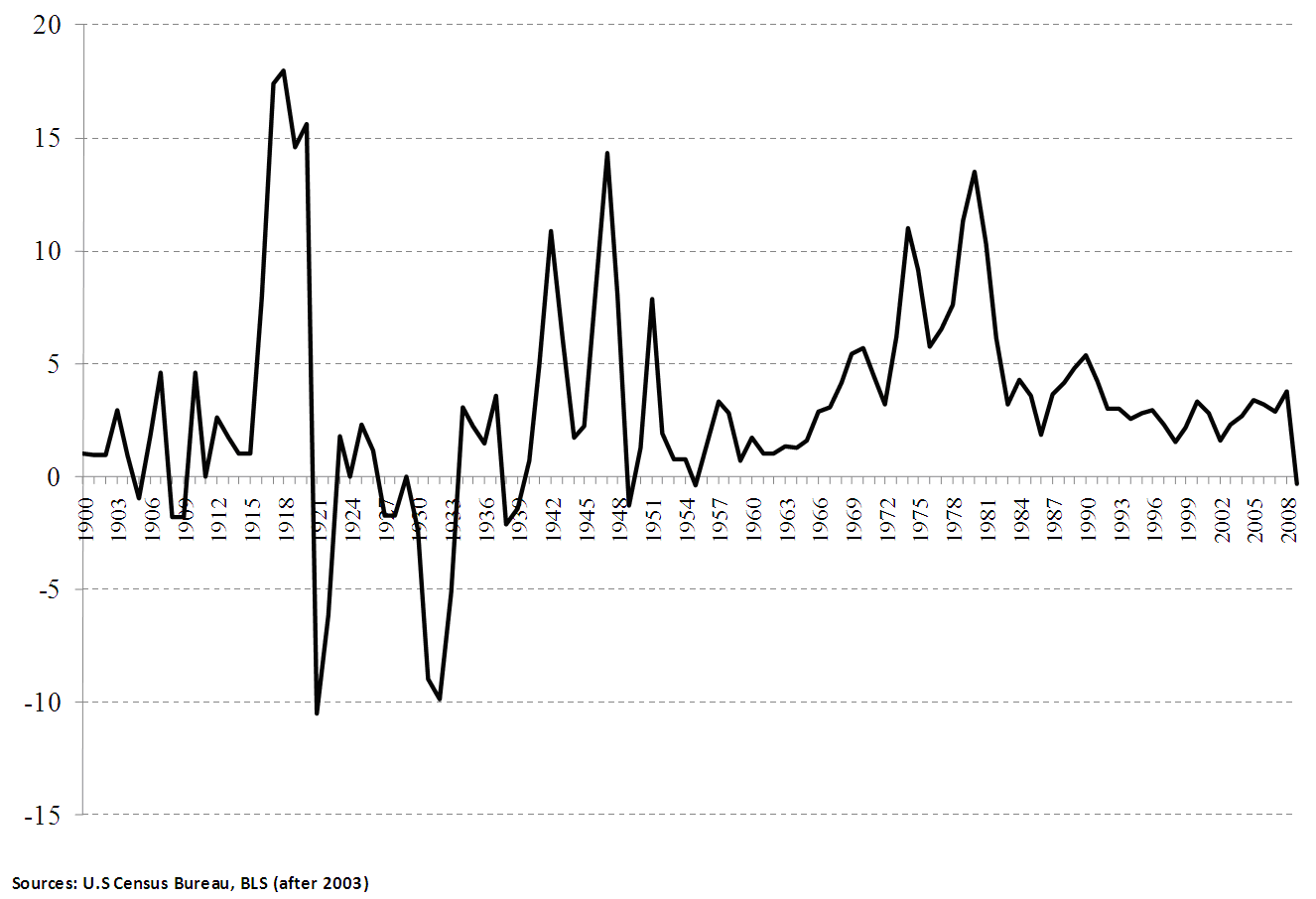

The problem is Europe-wide and indeed centered in the European Union capital in Brussels, where fifty to a hundred thousand workers gathered to protest the proposed transformation of social rules. Yet on the same day, the European Commission (EC) outlined a full-fledged war against labor. It is the most anti-labor campaign since the 1930s – even more extreme than the Third World austerity plans imposed by the IMF and World Bank in times past.

The EC is using the mortgage banking crisis – and the needless prohibition against central banks monetizing public budget deficits – as an opportunity to fine governments and even drive them bankrupt if they do not agree roll back salaries. Governments are told to borrow at interest from the banks, rather than raising revenue by taxing them as they did for half a century following the end of World War II. Governments unable to raise the money to pay the interest must close down their social programs. And if this shrinks the economy – and hence, government tax revenues – even more, the government must reduce social spending yet further.

From Brussels to Latvia, neoliberal planners have expressed the hope that lower public-sector salaries will spread to the private sector. The aim is to roll back wage levels by 30 percent or more, to depression levels, on the pretense that this will “leave more surplus” available to pay in debt service. It will do no such thing, of course. It is a purely vicious attempt to reverse Europe’s Progressive Era social democratic reforms achieved over the past century. Europe is to be turned into a banana republic by taxing labor – not finance, insurance or real estate (FIRE). Governments are to impose heavier employment and sales taxes while cutting back pensions and other public spending.

“Join the fight against labor, or we will destroy you,” the EC is telling governments. This requires dictatorship, and the European Central Bank (ECB) has taken over this power from elected government. Its “independence” from political control is celebrated as the “hallmark of democracy” by today’s new financial oligarchy. This deceptive newspeak evokes Plato’s view that oligarchy is simply the political stage following democracy. The new power elite’s next step in this eternal political triangle is to make itself hereditary – by abolishing estate taxes, for starters – so as to turn itself into an aristocracy.

It is a very old game indeed. So it is time to put aside the economics of Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill and the Progressive Era, to forget Marx and even Keynes. Europe is ushering in an era of totalitarian neoliberal rule. This is what Wednesday’s strikes and demonstrations were about. Europe’s class war is back in business – with a vengeance!

This is economic suicide, but the EU is demanding that Euro-zone governments keep their budget deficits below 3% of GDP, and their total debt below 60%. On Wednesday the EU passed a law to fine governments up to 0.2% of GDP for not “fixing” their budget deficits by imposing such fiscal austerity. Nations that borrow to engage in countercyclical “Keynesian-style” spending that raises their public debt beyond 60% of GDP will have to reduce the excess by 5% each year, or suffer harsh punishment.[1] The European Commission (EC) will fine euro-area states that do not obey its neoliberal recommendations – ostensibly to “correct” budget imbalances.

The reality is that every neoliberal “cure” only makes matters worse. But rather than seeing rising wage levels and living standards as being a precondition for higher labor productivity, the EU commission will “monitor” labor costs on the assumption that rising wages impair competitiveness rather than raise it. If euro members cannot depreciate their currencies, then they must fight labor – but not tax real estate, finance or other rentier sectors, not regulate monopolies, and not provide public services that can be privatized at much higher costs. Privatization is not deemed to impair competitiveness – only rising wages, regardless of productivity considerations.

The financial privatization and credit-creation monopoly that governments have relinquished to banks is now to really pay off – at the price of breaking up Europe. Unlike central banks elsewhere in the world, the charter of the European Central Bank (ECB, independent from democratic politics, not from control by its commercial bank members) forbids it to monetize government debt. Governments must borrow from banks, which are create interest-bearing debt on their own keyboards rather than having their national bank do it without cost.

The unelected members of the European Central Bank have taken over planning power from elected governments. Beholden to its financial constituency, the ECB has convinced the EU commission to back the new oligarchic power grab. This destructive policy has been tested above all in the Baltics, using them as guinea pigs to see how far labor can be depressed before it fights back. Latvia gave free reign to neoliberal policies by imposing flat taxes of 51% and higher on labor, while real estate is virtually untaxed. Public-sector wages have been reduced by 30%, prompting labor of working age (20 to 35 year-olds) to emigrate in droves. This of course is contributing to the plunge in real estate prices and tax revenue. Lifespans for men are shortening, disease rates are rising, and the internal market is shrinking, and so is Europe’s population – as it did in the 1930s, when the “population problem” was a plunge in fertility and birth rates (above all in France). That is what happens in a depression.

Iceland’s looting by its bankers came first, but the big news was Greece. When that nation entered its current fiscal crisis as a result of not collecting taxes on the wealthy, European Union officials recommended that it emulate Latvia, which remains the poster child for neoliberal devastation. The basic theory is that inasmuch as members of the euro cannot devalue their currency, they must resort to “internal devaluation”: slashing wages, pensions and social spending. So as Europe enters recession it is following precisely the opposite of Keynesian policy. It is reducing wages, ostensibly to “free” more income available to pay the enormous debts that Europeans have taken on to buy their homes and pay for schooling (hitherto provided freely in many countries such as Latvia’s Stockholm School of Economics), transportation and other public services. Manly such services have been privatized and subsequently raised their rates drastically. The privatizers justify this by pointing to the enormously bloated financial fees they had to pay their bankers and underwriters in order to get the credit to buy the infrastructure that was being sold off by governments.

So Europe is committing economic, demographic and fiscal suicide. Trying to “solve” the problem neoliberal style only makes things worse. Latvia’s public-sector workers, for example, have seen their wages cut by 30 percent over the past year, and its central bankers have told me that they are seeking further cuts, in the hope that this will lower wages in the private sector as well, just as neoliberals in other European countries hope, as noted above.

About 10,000 Latvians attended protest meetings in the small town of Daugavilpils alone as part of the “Journey into the Crisis.” In Latvia’s capital city, Riga, yesterday’s Action Day saw the usual stoppage of transportation and an accompanying honk concert for 10 minutes at 1 PM to let the public know that something was happening. Six independent trade unions and the Harmony Center organized a protest meeting in Riga’s Esplanade Park that drew 700 to 800 demonstrators, relatively large for so small a city. Another union protest saw about half that number gather at the Cabinet of Ministers where Latvia’s austerity program has been planned and carried out.

What is happening most importantly is the national parliamentary elections this Saturday (October 2). The leading coalition, Harmony Center, is pledged to enact an alternative tax and economic policy to the neoliberal policies that have reduced labor’s wages and workplace standards so sharply over the past decade. A few days earlier a bus tour drove journalists to the most visible victims – schools and hospitals that had been closed down, government buildings whose employees had seen their salaries slashed and the workforce downsized.

These demonstrations seem to have gained voter sympathy for the more militant unions, headed by the hundred individual unions belonging to the Independent Trade Union Association. The other union group – the Free Trade Unions (LBAS) lost face by acquiescing in June 2009 to the government’s proposed 10% pension cuts (and indeed, 70% for working pensioners). Latvia’s constitutional court was sufficiently independent to overrule these drastic cuts last December. And if the government does indeed change this Saturday, the conflict between the Neoliberal Revolution and the past few centuries of classical progressive reform will be made clear.

In sum, the Neoliberal Revolution seeks to achieve in Europe what the United States has achieved since real wages stopped rising in 1979: doubling the share of wealth enjoyed by the richest 1%. This involves reducing the middle class to poverty, breaking union power, and destroying the internal market as a precondition.

All this is being blamed on “Mr. Market” – presumably inexorable forces beyond politics, purely “objective,” a political power grab. But is not really “the market” that is promoting this destructive economic austerity. Latvia’s Harmony Center program shows that there is a much easier way to cut the cost of labor in half than by reducing its wages: Simply shift the tax burden off labor onto real estate and monopolies (especially privatized infrastructure). This will leave less of the economic surplus to be capitalized into bank loans, lowering the price of housing accordingly (the major factor in labor’s cost of living), as well as the price of public services. (Owners of monopoly utility services would be prevented from factoring interest charges into their cost of doing business. The idea is to encourage them to take returns on equity. Whether or not they borrow is a business decision of theirs, not one that governments should subsidize.) The tax deductibility of interest will be repealed – there is nothing intrinsically “market dictated” by this fiscal subsidy for debt leveraging. This program may be reviewed at rtfl.lv, the Renew Task Force Latvia website.

No doubt many post-Soviet economies will find themselves obliged to withdraw from the euro area rather than see a flight of labor and capital. They remain the most extreme example of the Neoliberal Experiment to see how far a population can have its living standards slashed before it rebels.

But so far the neoliberals are fully in control of the bureaucracy, and they are reviving Margaret Thatcher’s slogan, TINA: There Is No Alternative. But there is an alternative, of course. In the small Baltic economies, pro-labor parties are pressing for the government to shift the tax burden off employees and consumers back onto property and financial wealth. Bad debts beyond the reasonable ability to pay must be scaled back. It may be necessary to let the banks go under (they are mainly Swedish), even if this means withdrawing from the Euro. The choice is between who will be destroyed: the banks, or labor?

European politicians now view this as being truly a fight to the death. This is the ideology that has replaced social democracy.

[1] Matthew Dalton, “EU Proposes Fines for Budget Breaches,” Wall Street Journal, September 29, 2010.