Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

March 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

Tag Archives: International Finance

Debt and Democracy: Has the Link been Broken?

A longer version of the article will appear in the Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung on December 5th, 2011

Book V of Aristotle’s Politics describes the eternal transition of oligarchies making themselves into hereditary aristocracies – which end up being overthrown by tyrants or develop internal rivalries as some families decide to “take the multitude into their camp” and usher in democracy, within which an oligarchy emerges once again, followed by aristocracy, democracy, and so on throughout history.

Debt has been the main dynamic driving these shifts – always with new twists and turns. It polarizes wealth to create a creditor class, whose oligarchic rule is ended as new leaders (“tyrants” to Aristotle) win popular support by cancelling the debts and redistributing property or taking its usufruct for the state.

Why Iceland Voted “No”

By Michael Hudson

About 75% of Iceland’s voters turned out on Saturday to reject the Social Democratic-Green government’s proposal to pay $5.2 billion to the British and Dutch bank insurance agencies for the Landsbanki-Icesave collapse. Every one of Iceland’s six electoral districts voted in the “No” column – by a national margin of 60% (down from 93% in January 2010).

The vote reflected widespread belief that government negotiators had not been vigorous in pleading Iceland’s legal case. The situation is reminiscent of World War I’s Inter-Ally war debt tangle. Lloyd George described the negotiations between U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and Stanley Baldwin regarding Britain’s arms debt as “a negotiation between a weasel and its quarry. The result was a bargain which has brought international debt collection into disrepute … the Treasury officials were not exactly bluffing, but they put forward their full demand as a start in the conversations, and to their surprise Dr. Baldwin said he thought the terms were fair, and accepted them. … this crude job, jocularly called a ‘settlement,’ was to have a disastrous effect upon the whole further course of negotiations …”

And so it was with Iceland’s negotiation with Britain. True, they got a longer payment period for the Icesave payout. But how is Iceland to obtain the pounds sterling and Euros in the face of its shrinking economy. This is the major payment risk that is still unaddressed. It threatens to plunge the krona’s exchange rate.

Furthermore, the settlement included running interest charges on the bailout since 2008, even the extra-high interest charges that led depositors to put their funds in Icesave in the first place. Icelanders viewed these interest premiums as compensation for risks – that were taken and should be lost by the high-interest Internet depositors.

So the Icesave problem will now go to the courts. The relevant EU directive states “that the cost of financing such schemes must be borne, in principle, by credit institutions themselves.” As priority claimants Britain and the Netherlands will indeed get the lion’s share of what is left from the Landsbanki corpse. That was not the issue before Iceland’s voters. They simply aimed at saving Iceland from an open-ended obligation to take the bank’s losses onto the public balance sheet without a clear plan of just how Iceland is to get the money to pay.

Prime Minister Johanna Sigurdardottir warns that the vote may trigger “political and economic chaos.” But trying to pay also threatens this. The past year has seen the disastrous experience of Greece, Ireland and now Portugal in taking reckless private sector bank debts onto the public balance sheet. It is hard to expect any sovereign nation to impose a decade or more of deep depression on its economy inasmuch as international law permits every nation to act in its own vital interests.

Attempts by creditors to persuade nations to bail out their banks at public expense thus is ultimately an exercise in public relations. Icelanders have seen how successful Argentina has been since it imposed a crew haircut on its creditors. They also have seen the economic and political disruption in Ireland and Greece resulting from trying to pay beyond their means.

Creditors did not give accurate advice when they told Ireland that it could pay for its bank failures without plunging the economy into depression. Ireland’s experience stands as a warning to other countries about trusting overly optimistic forecasts by central bankers. In Iceland’s case, in November 2008 the IMF staff projected yearend-2009 gross external public and private debt at 160% of GDP – but observed that an exchange rate depreciation of 30% would push the ratio to 240% of GDP, which would be “clearly unsustainable.” But the most recent IMF staff report (January 14, 2011) shows end-2009 gross external debt at 308% of GDP, and estimates end-2010 gross external debt at 333% – even before taking the Icesave and other debts into account!

The main problem with Iceland’s obligation to Britain and the Netherlands is that foreign debt is not paid out of GDP. Apart from what is recovered from Landsbanki (now with the help of Britain’s Serious Fraud Office), the money must be paid in exports. But there has been no negotiation with Britain and Holland over just what Icelandic goods and services these countries would be willing to take in payment. Already in the 1920s, John Maynard Keynes pointed out that the Allied creditor nation had to take some responsibility just how Germany could pay its reparations, if not by exporting more to these countries. In practice, German cities borrowed in New York, turned the dollars over to the Reichsbank, which paid Britain and France, which paid the money back to the U.S. Government for their Inter-Ally Arms debts. In other words, Germany tried to “borrow its way out of debt.” It never works over time.

The normal practice would be for Iceland to appoint a Group of Experts to lay out the strongest possible case. No sovereign nation can be expected to acquiesce in imposing a generation of financial austerity, economic shrinkage and forced emigration of labor to pay for the failed neoliberal experiment that has dragged down so many other European economies.

Posted in Michael Hudson, Uncategorized

Tagged Financial crisis, Iceland, International Finance, Michael Hudson

FREDDIE MISHKIN DOES ICELAND: YOU’VE GOT TO TRUST THOSE CENTRAL BANKS

Another one in the category of “you just can’t make this up”. Recall that Fred Mishkin was on the Fed’s Board of Governors when the global financial system bombed. Now watch this:

For Mishkin’s report on Iceland, go here. For Tyler Durden’s commentary on the report and the video, go here.

If you are an academic, his performance makes you want to curl up under a table. If you are not in academics, it might make you want to take a baseball bat to the pointy-headed intellectuals at the nation’s “elite” universities. To be sure, what Columbia University’s Mishkin did to Iceland is no worse than what economics professors at Harvard—hey, Larry Summers, that includes you—have been doing to countries all over the world. The “research” they are paid to do is not research at all—it is marketing. In the case of Iceland, Freddie was paid by the Chamber of Commerce to do a fluff job—and he fluffed the heck out of Iceland. I wonder what the good people now suffering in Iceland would like to do with him.

One could give him a bit of slack—after all, why would anyone expect that Freddie knew anything at all about Iceland. His research method was to “talk to people” and to “trust the central bank”. That he didn’t see a financial collapse coming right around the corner isn’t, I guess, too surprising. Besides, if you are paid well to not see a crisis coming, you probably will not look too hard. Still, his squirming video takes the cake—even more fun than Geithner’s performances in front of Congress. Oh, right, his doctoring of his CV to change the title of his paper from “Stability” to “Instability” is a “typo”. And, right, he cannot remember how much he was paid as fluffer, but it is in the “public record”. Give us a break.

Actually, I had seen Mishkin squirm like that before. At the very beginning of the US financial crisis (April 2007)—when most still did not see it coming—Mishkin as member of the BOG gave a dinner speech. There was no indication in his speech that he “saw it coming”—he predicted moderate growth, emphasized some strong data in housing as well as low unemployment, and said the Fed would keep its interest rate target at 5.25. While it is hard to believe now, the Fed and most of the press was still worried about inflation at that time—even though anyone who was paying attention could see the economy was beginning to collapse into what would obviously be the worst crisis since the Great Depression. Still, commodities prices were being driven by a speculative boom coming mostly from pension funds—a story for another day. So Freddie was peppered with questions from the media present asking whether the Fed would be able to prevent an inflationary burst. Mishkin’s response was eerily similar to the response he gave in the video—you’ve got to trust the central bank. Do not worry, the Fed has ample ammunition to kill inflation.

When he returned to our table, we grilled him a bit more on that topic, and some of us also argued that the real danger facing the US was a financial crisis and deflation—not inflation. Let me interject that I liked Mishkin. He was a pleasant conversationalist, not at all arrogant, and even somewhat self-effacing. But when he gave his pat answer, “don’t worry, we are the Fed and we know what we are doing”, Jamie Galbraith pressed him for details: what are you going to do about inflation? And, if you raise interest rates now, when debt loads are so high, won’t that cause a wave of delinquencies on mortgages and consumer debt? That’s when we saw the same transformation you just witnessed in the video—from an easy, affable, confidence to sheer horror. Mishkin had been found out and was looking for the exits.

I must say that it was never clear exactly what that horror was. At the time I did not believe that Mishkin’s heart was in the inflation story. Surely he could not have believed, then, that the real danger was inflation. He’d been coached at the Fed about what he ought to say—and the Fed was riding the inflation story to divert attention away from the real danger. The Fed needed to keep the speculative bubbles going as long as possible—an election was around the corner and Republicans needed help. I was sure that he was actually afraid that we were right: the economy was going bust. And the Fed had nothing up its sleeve to prevent Armageddon.

Shortly thereafter, Mishkin left the Fed (August 2008—the second-shortest term ever served). That looked suspicious—and although I never tried to find out why, it fit with my interpretation that he knew what was coming, and so like Greenspan jumped the sinking ship before the Fed would be exposed as the impotent Wizard of Oz behind the curtain.

However, since then, Greenspan has publicly admitted that he had been clueless. His whole approach to economics was dangerously wrong. He never saw nothing coming. And after viewing this video, I am not so sure Mishkin had any clue, either.

Maybe his term at the Fed, like his research for Iceland, was nothing but marketing, too.

Columbia professor? Check.

NBER researcher? Check.

FDIC researcher? Check.

Highly paid consultant for international research? Check.

Vice President of NYFed? Check.

Former BOG member? Check.

Top selling money and banking textbook author? You betcha.

All he needed was a few months at the helm of the central bank, something he could add to the textbook blurb, to ramp up those sales.

Posted in L. Randall Wray, Uncategorized

Tagged Federal Reserve, Financial crisis, International Finance, L. Randall Wray

“My alternative proposal on trade with China”

By Warren Mosler*

We can have BOTH low priced imports AND good jobs for all Americans

Attorney General Richard Blumenthal has urged US Treasury Secretary Geithner to take legal action to force China to let its currency appreciate. As stated by Blumenthal: “By stifling its currency, China is stifling our economy and stealing our jobs. Connecticut manufacturers have bled business and jobs over recent years because of China’s unconscionable currency manipulation and unfair market practices.”

The Attorney General is proposing to create jobs by lowering the value of the dollar vs. the yuan (China’s currency) to make China’s products a lot more expensive for US consumers, who are already struggling to survive. Those higher prices then cause us to instead buy products made elsewhere, which will presumably means more American products get produced and sold. The trade off is most likely to be a few more jobs in return for higher prices (also called inflation), and a lower standard of living from the higher prices.

Fortunately there is an alternative that allows the US consumer to enjoy the enormous benefits of low cost imports and also makes good jobs available for all Americans willing and able to work. That alternative is to keep Federal taxes low enough so Americans have enough take home pay to buy all the goods and services we can produce at full employment levels AND everything the world wants to sell to us. This in fact is exactly what happened in 2000 when unemployment was under 4%, while net imports were $380 billion. We had what most considered a ‘red hot’ labor market with jobs for all, as well as the benefit of consuming $380 billion more in imports than we exported, along with very low inflation and a high standard of living due in part to the low cost imports.

The reason we had such a good economy in 2000 was because private sector debt grew at a record 7% of GDP, supplying the spending power we needed to keep us fully employed and also able to buy all of those imports. But as soon as private sector debt expansion reached its limits and that source of spending power faded, the right Federal policy response would have been to cut Federal taxes to sustain American spending power. That wasn’t done until 2003- two long years after the recession had taken hold. The economy again improved, and unemployment came down even as imports increased. However, when private sector debt again collapsed in 2008, the Federal government again failed to cut taxes or increase spending to sustain the US consumer’s spending power. The stimulus package that was passed almost a year later in 2009 was far too small and spread out over too many years. Consequently, unemployment continued to rise, reaching an unthinkable high of 16.9% (people looking for full time work who can’t find it) in March 2010.

The problem is we are conducting Federal policy on the mistaken belief that the Federal government must get the dollars it spends through taxes, and what it doesn’t get from taxes it must borrow in the market place, and leave the debts for our children to pay back. It is this errant belief that has resulted in a policy of enormous, self imposed fiscal drag that has devastated our economy.

My three proposals for removing this drag on our economy are:

1. A full payroll tax (FICA) holiday for employees and employers. This increases the take home pay for people earning $50,000 a year by over $300 per month. It also cuts costs for businesses, which means lower prices as well as new investment.

2. A $500 per capita distribution to State governments with no strings attached. This means $1.75 billion of Federal revenue sharing to the State of Connecticut to help sustain essential public services and reduce debt.

3. An $8/hr national service job for anyone willing and able to work to facilitate the transition from unemployment to private sector employment as the pickup in sales from my first two proposals quickly translates into millions of new private sector jobs.

Because the right level of taxation to sustain full employment and price stability will vary over time, it’s the Federal government’s job to use taxation like a thermostat- lowering taxes when the economy is too cold, and considering tax increases only should the economy ‘over heat’ and get ‘too good’ (which is something I’ve never seen in my 40 years).

For policy makers to pursue this policy, they first need to understand what all insiders in the Fed (Federal Reserve Bank) have known for a very long time- the Federal government (not State and local government, corporations, and all of us) never actually has nor doesn’t have any US dollars. It taxes by simply changing numbers down in our bank accounts and doesn’t actually get anything, and it spends simply by changing numbers up in our bank accounts and doesn’t actually use anything up. As Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke explained in to Scott Pelley on ’60 minutes’ in May 2009:

(PELLEY) Is that tax money that the Fed is spending?

(BERNANKE) It’s not tax money. The banks have– accounts with the Fed, much the same way that you have an account in a commercial bank. So, to lend to a bank, we simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account that they have with the Fed.

Therefore, payroll tax cuts do NOT mean the Federal government will go broke and run out of money if it doesn’t cut Social Security and Medicare payments. As the Fed Chairman correctly explained, operationally, spending is not revenue constrained.

We know why the Federal government taxes- to regulate the economy- but what about Federal borrowing? As you might suspect, our well advertised dependence on foreigners to buy US Treasury securities to fund the Federal government is just another myth holding us back from realizing our economic potential.

Operationally, foreign governments have ‘checking accounts’ at the Fed called ‘reserve accounts,’ and US Treasury securities are nothing more than savings accounts at the same Fed. So when a nation like China sells things to us, we pay them with dollars that go into their checking account at the Fed. And when they buy US Treasury securities the Fed simply transfers their dollars from their Fed checking account to their Fed savings account. And paying back US Treasury securities is nothing more than transferring the balance in China’s savings account at the Fed to their checking account at the Fed. This is not a ‘burden’ for us nor will it be for our children and grand children. Nor is the US Treasury spending operationally constrained by whether China has their dollars in their checking account or their savings accounts. Any and all constraints on US government spending are necessarily self imposed. There can be no external constraints.

In conclusion, it is a failure to understand basic monetary operations and Fed reserve accounting that caused the Democratic Congress and Administration to cut Medicare in the latest health care law, and that same failure of understanding is now driving well intentioned Americans like Atty General Blumenthal to push China to revalue its currency. This weak dollar policy is a misguided effort to create jobs by causing import prices to go up for struggling US consumers to the point where we buy fewer Chinese products. The far better option is to cut taxes as I’ve proposed, to ensure we have enough take home pay to be able to buy all that we can produce domestically at full employment, plus whatever imports we want to buy from foreigners at the lowest possible prices, and return America to the economic prosperity we once enjoyed.

*This article first appeared on moslereconomics.com

Posted in Uncategorized, Unemployment

Tagged International Finance, The Trade Deficit, unemployment

“Britain Not Part of Any Greek Tragedy”

They certainly know what “schadenfreude” means in Germany. But the attempt by the German paper, Der Spiegel, to link the UK to the travails of Greece, takes the concept to a malicious and irrational extreme:

The British pound is tottering. The economy finds itself in its worst crisis since 1931, and the country came within a hair’s breadth of a deep recession. Speculators are betting against an upturn. Instability in the banking sector has had a more severe impact on government finances in Great Britain than in other industrialized countries. London’s budget deficit will amount to £186 billion (€205 billion, or $280 billion) this year — fully 12.9 percent of gross domestic product.

Sounds pretty, grim, especially given that Britain’s budget deficit is even higher than that of the “corrupt” Greeks, whom the Germans also seem so intent on abusing in print and punishing for their alleged fiscal profligacy.

But the article itself is rife with intellectual dishonesty. You cannot mindlessly conflate EMU states — Germany included — which operate with no real fiscal authority as sovereign states in the full sense — with countries, such as the United Kingdom, which fortunately has a government with currency issuing monopolies operating under flexible exchange rates (even though the British haven’t quite figured it out). And, as strange as it may sound, public sector profligacy at this time is preferable to Germanic style prudence, because as the private sector’s spending and borrowing go into hibernation, government borrowing must expand significantly to compensate. Even the French Finance Minister, Christine Lagarde, seems to understand that fact (and is taking heat from her German “allies” as a result). Her sin? She had the temerity to suggest that Berlin should consider boosting domestic demand to help deficit countries regain competitiveness and sort out their public finances. Noting that “it takes two to tango”, Lagarde suggested that an expansionary fiscal policy had a role to play here, not simply “enforcing deficit principles”.

Of course, that’s harder to do in the euro zone, given the insane constraints put forward as a condition of euro entry. As a consequence of these rules, the EMU nations cannot even run their own region properly. They have established a system which has consistently drained aggregate demand and brought increasingly high levels of unemployment to bear on their respective populations. In the words of Bill Mitchell:

The rules that the EU made up and then imposed on the EMU via the Maastricht Treaty’s Stability and Growth Pact were not based on any coherent models of fiscal sustainability or variations that might be encountered in these aggregates during a swing in the business cycle. The rules are biased towards high unemployment and stagnant growth of the sort that has bedeviled Europe for years.

Having conspicuously failed to deliver prosperity to their own countrymen, the Germans now see fit to lecture the UK (after taking out the Greeks, of course) on the grounds of Britain’s “crass Keynesianism” (in the words of Axel Weber, the President of the German Bundesbank).

There is no question that the UK has some unique features which make it more than just another casualty of the global credit crunch. It foolishly leveraged its growth strategy to the growth in financial services and is now paying the price for that misconceived policy, as the industry inevitably contracts and restructures as a percentage of GDP. This structural headwind will no doubt force the UK authorities to adopt an even more aggressive fiscal posture than would normally be the case. This is politically problematic, given that the vast majority of the UK’s policy makers (and the chattering classes in the media) still cling to the prevailing deficit hysteria now taking hold all over the world. But the reality is that the UK has considerably greater fiscal latitude of action than any of the euro zone countries, including Germany.

Let’s go back to first principles: In a country with a currency that is not convertible upon demand into anything other than itself (no gold “backing”, no fixed exchange rate), the government can never run out of money to spend, nor does it need to acquire money from the private sector in order to spend. This does not mean the government doesn’t face the risk of inflation, currency depreciation, or capital flight as a result of shifting private sector portfolio preferences. But the budget constraint on the government, the monopoly supplier of currency, is different than what most have been taught from classical economics, which is largely predicated on the notion of a now non-existent gold standard. The UK Treasury cuts you a benefits check, your check account gets credited, and then some reserves get moved around on the Bank of England’s balance sheet and on bank balance sheets to enable the central bank (in this case, the Bank of England) to hit its interest rate target. If anything, some inflation would probably be a good thing right now, given the prevailing high levels of private sector debt and the deflationary risk that PRIVATE debt represents because of the natural constraints against income and assets which operate in the absence of the ability to tax and create currency.

Unlike Germany, or any other EMU nation, there is no notion of “national solvency” that applies here, so the idea that the UK should follow Greece down the road to national suicide reflects nothing more than the traditional German predisposition to sado-monetarism and deficit reduction fetishism. A commitment to close the deficit is also what doomed Japan throughout most of the 1990s and 2000s, when foolish premature attempts at “fiscal consolidation” actually increased budget deficits by deflating incipient economic activity. Why would you tighten fiscal policy when there is anemic private demand and unemployment is still high?

Remember Accounting 101. It is the reversal of trade deficits and the increase in fiscal deficits, which gets a country to an increase in net private saving, ASSUMING NO STUPID SELF IMPOSED CONSTRAINTS along the lines proposed by Germany under the Stability and Growth Pact (which should be re-christened the “Instability and Non-Growth Pact”). Ideally, we want the deficits to be achieved in a good way: not with automatic stabilizers driving the budget into deficit because unemployment is rising and tax revenue is falling as private demand falters, but one in which a government uses discretionary fiscal policy to ensure that demand is sufficient to support high levels of employment and private saving. That in turn will stabilize growth and improve the deficit picture. Once this is achieved, any notions of national insolvency (or more “Greek tragedies”) should go out the window.

The UK can do this, even if its policy makers fail to recognize this. But not in the eyes of Der Spiegel, which warns that “tough times are ahead for the United Kingdom, so tough, in fact, that none of the parties has dared to say out loud what many in their ranks already know. At a minimum, Britons can look forward to higher taxes and fees.” And much lower growth if that prescription is followed.

We suspect that many in Germany and the rest of Europe understand this. So what other motivations are at work here? Clearly, calling attention to the state of Britain’s public finances and drawing specious comparisons to Greece in effect invites speculative capital to take its collective eye off the euro zone and focus it on the UK. Given that the alleged “Greek solution” proposed recently by the European Commission does nothing to resolve the country’s underlying problems, it behooves the euro zone countries to draw attention elsewhere before their collective resolve to defend their currency union comes under attack again.

And heaven forbid that the UK was actually successful (admittedly unlikely today, given the paucity of British political leaders who truly understand how modern money actually works). If Her Majesty’s Government spending actually managed to conduct fiscal policy in a manner which supported higher levels of employment and a more equitable transfers of national income (via, for example, a government Job Guarantee program) then what would be the response in the euro zone? Wouldn’t this cause its citizens to query what sort of bogus economic “expertise” that has been fed to them from their technocratic elites over the past two decades? The same sort of neo-liberal pap fed to the US courtesy of groups such as the Concord Coalition.

No question that public spending should be carefully mobilized to ensure that it is consonant with national purpose (not corporate cronyism). But the idea perpetuated by Der Spiegel that the government is somehow constrained by some self imposed rules with no reference to the underlying economy is comedy worthy of a Brechtian farce. Unfortunately, this particular German joke is no laughing matter.

*This post originally appeared on new deal 2.0

Posted in Marshall Auerback, Uncategorized

Greece Cannot Reduce Its Budget Deficit So Long As Its Neighbors Pursue Mercantilist Policy

By Yeva Nersisyan

When the 12 European Nations raced to embrace the single currency, euro, it was supposed to be a forward step in the process of European Integration, towards the United States of Europe. In retrospect, the euro has not only not contributed to deeper integration but is certainly close to undermining its foundations. The economic and debt crises have forced countries to resort back to their bitter past relations up to the point where Greeks are demanding that Germany pay WWII reparations.

Much has been said about Greece’s debt crisis with a few proposals on how it should deal with it. All of these eventually turn into proposals of how the Greeks should manage their own country. A recent article in the New York Times critically examines Greece’s pension system which has 580 occupations that qualify for early retirement at the age 50. Greece has promised early retirement to about 700,000 workers and its average retirement age is one of the lowest in Europe, 61. While the effectiveness or the reasonableness of the Greek pension system is beyond the scope of this blog, what is incomprehensible is how does a developed and politically sovereign nation such as Greece completely give up its domestic policy space, up to the point where it is told what to do about its pensioners, how to behave with the unions, what to do about public sector wages, etc? Politicians, rating agencies and media commentators somehow feel that they all have the right to give some advice on how the Greek government should manage their country. As long as we know, Greece is a representative democracy where the people elect their government and can demand that it do whatever it has promised to its population. It is up to the people of Greece, through the Greek government to decide what to do with their country, not to us, to you and especially not to the fraudulent and corrupt rating agencies and media commentators looking to make a career. Moreover, it sounds like Greece is simply trying to solve its unemployment problems by making people retire earlier. Prolonging the retirement age won’t do much to solve the problem, as the government will still need to spend to boost aggregate spending to create jobs for all those people.

Most commentators of course overlook the main issue which is that by entering the monetary union and divorcing fiscal and monetary authorities individual nations have given up their currency issuing capacity. So unlike the Untied States government that spends by simply crediting bank accounts, i.e. changing numbers on spreadsheets (see here), the Greek and even German governments need to have tax and bond revenues prior to spending. But euronations differ vastly in their ability to collect taxes and raise revenue through bond sales. The convergence in debt levels, interest rates and number of other economic variables among individual countries that was being predicted by mainstream economists never really materialized. Germany and to some degree France have remained the important players in the euro landscape reserving the right to dictate policy prescriptions to their less powerful southern neighbors. At this point, Greece largely depends on Germany to determine its fate. It is now similar to a developing country being told what policy to implement by the IMF, only in this case it’s Germany that has assumed the role of the IMF.

It is useful to recall the financial balance identity for analyzing what policy options Greece has (see here). The balance of the private sector (surplus/deficit) equals the balance of the government (deficit/surplus) plus the current account balance (surplus/deficit). In plain English this means that private sector savings (surplus) is financed by government deficit (an injection into private incomes and hence saving) and by the current account surplus (net exports are an injection into nominal income and hence saving). By entering the monetary union the euronations have voluntarily agreed to the debt and deficit constraints imposed by the Maastricht treaty. So what are the policy options for these countries under these self-imposed constraints? We know that the private sector cannot be perpetually in deficit; in fact the normal situation is for the private sector to try to save some of its income. The current account balance of Greece was -9.98% in 2009. If Greece only had a budget deficit of 3% (the Maastricht limit) then its private sector would need to run a deficit of 6.98%. If we want the Greeks to have a positive saving (>0) what needs to be true about the government deficit? Simple math will show that it has to be greater than 9.98% of GDP. So to balance its budget, either the private sector needs to go in debt (making bankers richer) or Greece needs to balance its current account and even try to achieve a small surplus which is neither desirable nor achievable.

But what happens when all euronations try to export their way out of their economic problems? Basically, they will have to revert to mercantilist-type beggar-thy-neighbor policies where each country tries to solve its growth and unemployment problems by exporting them to their trading partners. Germany has already taken this route which has allowed it to be a “role model” for “fiscal responsibility” and given it the “right” to criticize other countries which don’t follow it. But all the countries cannot be net exporters; some have to be net importers. Germany can only be a net exporter to Euroland if some other euro nations are willing to be on the other end of the transaction. France, Italy, Belgium and Spain are among the 11 largest export partners of Germany with each of these countries having a net deficit with it. It is the government or private deficit in these countries that’s financing Germany’s exports.

So what options do net importer countries such as Greece or Spain have to maintain their aggregate demand at a reasonable level? If sovereign indebtedness is not acceptable, the only thing left is private sector indebtedness which will eventually lead to a financial collapse as we have witnessed in the US, UK and elsewhere. And some countries such as Spain don’t even have that option as their private sector is already highly indebted.

To summarize, the problem is not Greece’s profligate spending, but rather the design of the European monetary system. It has been specifically created to divorce the monetary and fiscal authorities to make the monetary authority super independent from “political pressures”. It has tied the hands of governments restricting them in using their fiscal capacity to employ their labor resources and has forced the countries into sluggish growth, high unemployment rates, stagnating wages, cuts in social services, etc. They have been able to achieve low inflation rates though. What a fair trade-off! Moreover, as countries on the periphery approach the Maastricht debt limits, the markets start betting against the country’s debt forcing it to pay higher interest rates. And of course no mess is complete without the rating agencies which are “diligently” monitoring the debt and deficit situations threatening to cut countries’ ratings further exacerbating the problem.

If Germany wants to increase its retirement age and cut social benefits it should be up to the German public to accept it or protest against it. But foreigners shouldn’t be allowed to dictate this to Greece and other nations. If they are doing that, and successfully so, it means that something is wrong with the way the system is set up. It is time for Greece and other nations in the outskirts of Europe to push for a change in the institutional structure which is obviously dysfunctional.

Will the Quest for Fiscal Sustainability Destabilize Private Debt?

By Robert Parenteau, CFA*

The question of fiscal sustainability looms large at the moment – not just in the peripheral nations of the eurozone, but also in the UK, the US, and Japan. More restrictive fiscal paths are being proposed in order to avoid rapidly rising government debt to GDP ratios, and the financing challenges they may entail, including the possibility of default for nations without sovereign currencies.

However, most of the analysis and negotiation regarding the appropriate fiscal trajectory from here is occurring in something of a vacuum. The financial balance approach reveals that this way of proceeding may introduce new instabilities (see here and here). Intended changes to the financial balance of one sector can only be accomplished if the remaining sectors also adjust. Pursuing fiscal sustainability along currently proposed lines is likely to increase the odds of destabilizing the private sectors in the eurozone and elsewhere – unless an offsetting increase in current account balances can be accomplished in tandem.

To make the interconnectedness of sector financial balances clearer, proposed fiscal trajectories need to be considered in the context of what we call the financial balances map. Only then can tradeoffs between fiscal sustainability efforts and the issue of financial stability for the economy as a whole be made visible. Absent consideration of the interrelated nature of sector financial balances, unnecessarily damaging choices may soon be made to the detriment of citizens and firms in many nations.

Navigating the Financial Balances Map

For the economy as a whole, in any accounting period, total income must equal total expenditures. There are, after all, two sides to every transaction: a spender of money and a receiver of money income. Similarly, total saving out of income flows must equal total investment in tangible capital during any accounting period.

For individual sectors of the economy, these equalities need not hold. The financial balance of any one sector can be in surplus, in balance, or in deficit. The only requirement is, regardless of how many sectors we choose to divide the whole economy into, the sum of the sectoral financial balances must equal zero.

For example, if we divide the economy into three sectors – the domestic private (households and firms), government, and foreign sectors, the following identity must hold true:

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance + Foreign Financial Balance = 0

Note that it is impossible for all three sectors to net save – that is, to run a financial surplus – at the same time. All three sectors could run a financial balance, but they cannot all accomplish a financial surplus and accumulate financial assets at the same time – some sector has to be issuing liabilities.

Since foreigners earn a surplus by selling more exports to their trading partners than they buy in imports, the last term can be replaced by the inverse of the trade or current account balance. This reveals the cunning core of the Asian neo-mercantilist strategy. If a current account surplus can be sustained, then both the private sector and the government can maintain a financial surplus as well. Domestic debt burdens, be they public or private, need not build up over time on household, business, or government balance sheets.

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance – Current Account Balance = 0

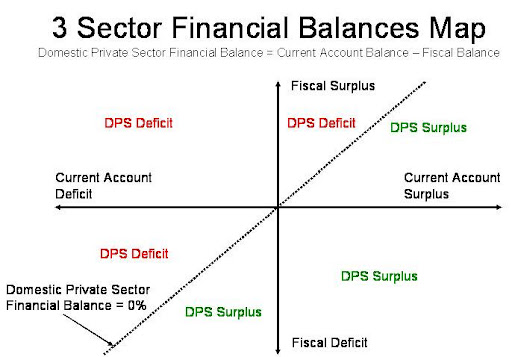

Again, keep in mind this is an accounting identity, not a theory. If it is wrong, then five centuries of double entry book keeping must also be wrong. To make these relationships between sectors even clearer, we can visually represent this accounting identity in the following financial balances map as displayed below.

On the vertical axis we track the fiscal balance, and on the horizontal axis we track the current account balance. If we rearrange the financial balance identity as follows, we can also introduce the domestic private sector financial balance to the map:

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance = Current Account Balance – Fiscal Balance

That means at every point on this map where the current account balance is equal to the fiscal balance, we know the domestic private sector financial balance must equal zero. In other words, the income of households and businesses just matches their expenditures (or alternatively, if you prefer, the saving out of income flows by the domestic private sector just matches the investment expenditures of the sector). The dotted line that passes through the origin at a 45 degree angle marks off the range of possible combinations where the domestic private sector is neither net issuing financial liabilities to other sectors, nor is it net accumulating financial assets from other sectors.

Once we mark this range of combinations where the domestic private sector is in financial balance, we also have determined two distinct zones in the financial balance map. To the left of the dotted line, the current account balance is less than the fiscal balance: the domestic private sector is deficit spending. To the right of the dotted line, the current account balance is greater than the fiscal balance, and the domestic private sector is running a financial surplus or net saving position.

This follows from the recognition that a current account surplus presents a net inflow to the domestic private sector (as export income for the domestic private sector exceeds their import spending), while a fiscal surplus presents a net outflow for the domestic private sector (as tax payments by the private sector exceed the government spending they receive).

Accordingly, the further we move up and to the left of the origin (toward the northwest corner of the map), the larger the deficit spending of households and firms as a share of GDP, and the faster the domestic private sector is either increasing its debt to income ratio, or reducing its net worth to income ratio (absent an asset bubble). Moving to the southeast corner from the origin takes us into larger domestic private surpluses.

The financial balance map forces us to recognize that changes in one sector’s financial balance cannot be viewed in isolation, as is the current fashion. If a nation wishes to run a persistent fiscal surplus and thereby pay down government debt, it needs to run an even larger trade surplus, or else the domestic private sector will be left stuck in a persistent deficit spending mode.

When sustained over time, this negative cash flow position for the domestic private sector will eventually increase the financial fragility of the economy, if not insure the proliferation of household and business bankruptcies. Mimicking the military planner logic of “we must bomb the village in order to save the village”, the blind pursuit of fiscal sustainability may simply induce more financial instability in the private sector.

Leading the PIIGS to an (as yet) Unrecognized Slaughter

The rules of the eurozone are designed to reduce the room for policy maneuver of any one member country, and thereby force private markets to act as the primary adjustment mechanism. Each country is subject to a single monetary policy set by the European Central Bank (ECB). One policy rate must fit the needs of all the member nations in the Eurozone. Each country has relinquished its own currency in favor of the euro. One exchange rate must fit the needs of all member nations in the Eurozone. The fiscal balance of member countries is also, under the provisions of the Stability and Growth Path, supposed to be limited to a deficit of 3% of GDP. The principle here is one of stabilizing or reducing government debt to GDP ratios. Assuming economies in the Eurozone have the potential to grow at 3% of GDP in nominal terms, only fiscal deficits greater than 3% of GDP will increase the public debt ratio.

In other words, to join the European Monetary Union, nations have substantially diluted their policy autonomy. Markets mechanisms must achieve more of the necessary adjustments – policy measures are circumscribed. Policy responses are constrained by design, and experience suggests relative price adjustments in the marketplace have a difficult time at best of automatically inducing private investment levels consistent with desired private saving at a level of full employment income.

Now let’s layer on top of this structure three complicating developments of late. First, current account balances in a number of the peripheral nations have fallen, in part due to the prior strength in the euro. Second, fiscal shenanigans along with a very sharp global recession have led to very large fiscal deficits in a number of peripheral nations. Third, following the Dubai World debt restructuring, global investors have become increasingly alarmed about the sustainability of fiscal trajectories, and there is mounting pressure for governments to commit to tangible plans to reduce fiscal deficits over the next three years, with Ireland and Greece facing the first wave of demands for fiscal retrenchment.

We can apply the financial balances approach to make the current predicament plain. If, for example, Spain is expected to reduce it’s fiscal deficit from roughly 10% of GDP to 3% of GDP in three years time, then the foreign and private domestic sectors must be together willing and able to reduce their financial balances by 7% of GDP. Spain is estimated to be running a 4.5% of GDP current account deficit this year. If Spain cannot improve its current account balance (in part because it relinquished its control over its nominal exchange rate the day it joined EMU), the arithmetic of sector financial balances is clear. Spain’s households and businesses would, accordingly, need to reduce their current net saving position by 7% of GDP over the next three years. Since they are currently estimated to be net saving 5.5% of GDP, Spain’s domestic private sector would move to a 1.5% of GDP deficit, and thereby enter a path of increasing leverage.

Spain already is running one of the higher private debt to GDP ratios in the region. In addition, Spain had one of the more dramatic housing busts in the region, which Spanish banks are still trying to dig themselves out from (mostly, it is alleged, by issuing new loans to keep the prior bad loans serviced, in what appears to be a Ponzi scheme fashion). It is highly unlikely Spanish businesses and households will voluntarily raise their indebtedness in an environment of 20% plus unemployment rates, combined with the prospect of rising tax rates and reduced government expenditures as fiscal retrenchment is pursued.

Alternatively, if we assume Spain’s private sector will attempt to preserve its estimated 5.5% of GDP financial balance, or perhaps even attempt to run a larger net saving or surplus position so it can reduce its private debt faster, Spain’s trade balance will need to improve by more than 7% of GDP over the next three years. Barring a major surge in tradable goods demand in the rest of the world, or a rogue wave of rapid product innovation from Spanish entrepreneurs, there is an additional way for Spain to accomplish such a significant reversal in its current account balance.

Prices and wages in Spain’s tradable goods sector will need to fall precipitously, and labor productivity will have to surge dramatically, in order to create a large enough real depreciation for Spain that its tradable products gain market share (at, we should mention, the expense of the rest of the Eurozone members). Arguably, the slack resulting from the fiscal retrenchment is just what the doctor might order to raise the odds of accomplishing such a large wage and price deflation in Spain. But how, we must wonder, will Spain’s private debt continue to be serviced during the transition as Spanish household wages and business revenues are falling under higher taxes or lower government spending?

Part II Spain Ensnared in the EMU Trap

As evident from the financial balances map, there are a whole range of possible combinations of current account and domestic private sector financial balances which could be consistent with the 7% of GDP reduction in Spain’s fiscal deficit. But the simple yet still widely unrecognized reality is as follows: both the public sector and the domestic private sector cannot deleverage at the same time unless Spain produces a nearly unimaginable trade surplus – unimaginable especially since Spain will not be the only country in Europe trying to pull this transition off.

As an admittedly rough exercise, we can assume each of the peripheral nations will be constrained to achieving a fiscal deficit that does not exceed 3% of GDP in three years time. In addition, we will assume each nation finds some way to improve its current account imbalances by 2% of GDP over the same interval. What, then, are the upper limits implied for domestic private sector financial balances as a share of GDP for each nation?

Greece and Portugal appear most at risk of facing deeper private sector deficit spending under the above scenario, while Spain comes very close to joining them. But that obscures another point which is worth emphasizing. With the exception of Italy, this scenario implies declines in private sector balances as a share of GDP ranging from 3% in Portugal to nearly 9% in Ireland.

Private sectors agents only tend to voluntarily target lower financial balances in the midst of asset bubbles, when, for example home prices boom and gross personal saving rates fall. Alternatively, during profit booms, firms issue debt and reinvest well in excess of their retained earnings in order take advantage of an unusually large gap between the cost of capital and the expected return on capital. We have no compelling reasons to believe either of these conditions is immediately on the horizon.

The above conclusion regarding the need for a substantial trade balance swing flows in a straightforward fashion from the financial balance approach, and yet it is obviously being widely ignored, because the issue of fiscal retrenchment is being discussed as if it had no influence on the other sector financial balances. This is unmitigated nonsense. It is even more retrograde than primitive tales of “twin deficits” (fiscal deficits are nearly guaranteed to produce offsetting current account deficits) or Ricardian Equivalence stories (fiscal deficits are nearly guaranteed to produce offsetting domestic private sector surpluses) mainstream economists have been force feeing us for the past three decades. Both of these stories reveal an incomplete understanding of the financial balance framework – or at best, one requiring highly restrictive (and therefore highly unrealistic) assumptions.

The EMU Triangle

This observation is especially relevant in the Eurozone, as the combination of the policy constraints that were designed into the EMU, plus the weak trade positions many peripheral nations have managed to achieve, have literally backed these countries into a corner. To illustrate the nature of their conundrum, consider the following application of the financial balances map.

First, a constraint on fiscal deficits to 3% of GDP can be represented as a line running parallel to and below the horizontal axis. Under Stability and Growth Pact rules, we must define all combinations of sector financial balance in the region below this line as inadmissible. Second, since current account deficits as a share of GDP in the peripheral nations are running anywhere from near 2% in Ireland to over 10% in Portugal, and changes in nominal exchange rates are ruled out by virtue of the currency union, we can provisionally assume a return to current account surpluses in these nations is at best a bit of a stretch. This eliminates the financial balance combinations available in the right hand half of the map.

If peripheral European nations wish to avoid higher private sector deficit spending – and realistically, for most of the peripheral countries, the question is whether private sectors can be induced to take on more debt anytime soon, and whether banks and other creditors will be willing to lend more to the private sector following a rash of burst housing bubbles, and a severe recession that is not quite over – then there is a very small triangle that captures the range of feasible solutions for these nations on the financial balance map.

It is the height of folly to expect peripheral Eurozone nations to sail their way into the EMU triangle under even the most masterful of policy efforts or price signals. More likely, since reducing trade deficits is likely to prove very challenging (Asia is still reliant on export led growth, while US consumer spending growth is still tentative), the peripheral nations in the Eurozone will find themselves floating somewhere out to the northwest of the EMU triangle. The sharper their fiscal retrenchments, the faster their private sectors will run up their debt to income ratios.

Alternatively, if households and businesses in the peripheral nations stubbornly defend their current net saving positions, the attempt at fiscal retrenchment will be thwarted by a deflationary drop in nominal GDP. Demands to redouble the tax hikes and public expenditure cuts to achieve a 3% of GDP fiscal deficit target will then arise. Private debt distress will also escalate as tax hikes and government expenditure cuts the net flow of income to the private sector. Call it the paradox of public thrift.

As it turns out, pursuing fiscal sustainability as it is currently defined will in all likelihood just lead many nations to further private sector debt destabilization. European economic growth will prove extremely difficult to achieve if the current fiscal “sustainability” plans are carried out. Realistically, policy makers are courting a situation in the region that will beget higher private debt defaults in the quest to reduce the risk of public debt defaults through fiscal retrenchment. European banks, which remain some of the most leveraged banks, will experience higher loan losses, and rating downgrades for banks will substitute for (or more likely accompany) rating downgrades for government debt. A fairly myopic version of fiscal sustainability will be bought at the price of a larger financial instability.

Summary and Conclusions

These types of tradeoffs are opaque now because the fiscal balance is being treated in isolation. Implicit choices have to be forced out into the open and coolly considered by both investors and policy makers. It is not out of the question that fiscal rectitude at this juncture could place the private sectors of a number of nations on a debt deflation path – the very outcome policy makers were frantically attempting to prevent but a year ago.

There may be ways to thread the needle – Domingo Cavallo’s recent proposal to pursue a “fiscal devaluation” by switching the tax burden in Greece away from labor related costs like social security taxes to a higher VAT could be one way to effectively increase competitiveness without enforcing wage deflation. Cavallo’s claims to the contrary, however, it was not the IMF that tripped him up. Fiscal cuts begat lower domestic income flows, which led to tax shortfalls, missed fiscal balance targets, and another round of fiscal retrenchment, in a vicious spiral fashion. But more innovative solutions than these, where financial stability, not just fiscal sustainability, is the primary objective, will not even be brought to light unless policy makers and investors begin to think coherently about how financial balances interact.

Or to put it more bluntly, if European countries try to return to 3% fiscal deficits by 2012, as many of them are now pledging, unless the euro devalues enough, then either a) the domestic private sector will have to adopt a deficit spending trajectory, or b) nominal private income will deflate, and Irving Fisher’s paradox will apply (as in the very attempt to pay down debt leads to more indebtedness), thwarting the ability of policy makers to achieve fiscal targets. In the case of Spain, with large private debt/income ratios, this is an especially critical issue.

The underlying principle flows from the financial balance approach: the domestic private sector and the government sector cannot both deleverage at the same time unless a trade surplus can be achieved and sustained. We remain hard pressed to identify which nations or regions of the remainder of the world are prepared to become consistently larger net importers of Europe’s tradable products, but it is also said that necessity is the mother of all invention (and desperation, its father?). Pray there is life on Mars that consumes olives, red wine, and Guinness beer.

Rob Parenteau, CFA

MacroStrategy Edge

February 22, 2010

* This article originally appeared on NakedCapitalism here and here.

“Greece Signs its National Suicide Pact”

Agreement has been reached in Europe on a “rescue” package for Greece. But it’s no cause for celebration. It’s the kind of “rescue” sensation one experiences after paying out what’s left in one’s wallet when confronted with a robber with a gun. The insanity of self-imposed budgetary constraints will be manifest to all soon enough. Economists and the EU bureaucrats who advocate a slavish adherence to arbitrary compliance numbers fail to comprehend the basis of government spending. In imposing these voluntary financial constraints on government activity, they deny essential government services and the opportunity for full employment to their citizenry.

Score another one, then, for the high priests of fiscal rectitude. Harsh cuts, tax increases — this is by no means a recovery policy. The capital markets have got their pound of flesh. But Greece is no more able to reduce its deficit under these circumstances than it is possible to get blood out of a stone. Politically, it means ceding control of EU macro policy to an external consortium dominated by France and Germany. Greece becomes a colony.

Nor will the policies work, as the ’strict enough conditions’ imposed will further weaken demand in Greece and, consequently, the rest of the European Union. Furthermore, the rapidly expanding deficit of Greece has benefited the entire EU because it supported aggregated demand at the margin, and the sudden reversal contemplated by this package will reverse those forces.

The requirement that budget deficits should be zero on average and never exceed 3 per cent of GDP or gross national debt levels should not exceed 60 per cent of GDP not only restrict the fiscal powers that governments would ordinarily enjoy in fiat currency regimes, but also violates an understanding of the way fiscal outcomes are effectively endogenous, as Bill Mitchell has noted on several occasions.

Meanwhile, Greece and the rest of the Euro zone is being revealed as necessarily caught in a continual state of Ponzi style financing that demands institutional resolution of some sort to be sustainable. The separation of the monetary authorities from the fiscal authorities and the decentralization of the fiscal authorities have inevitably made any co-ordination of fiscal and monetary policy difficult. The ECB is effectively the only “federal” institution within the euro zone. This is particularly problematic during times of financial stress or in periods in which there is marked regional disparity in economic performance.

In the short term, a move by the ECB to distribute 1 trillion euro to the national governments on a per capita basis would alleviate the short term problems of the “PIIGS” nations (Portugal, Ireland,. Italy, Greece and Spain). Ultimately, though, the most logical solution is the creation of a supranational entity that can conduct fiscal policy in much the same way as the creation of the European Central Bank can do monetary policy on a supranational level (or the dissolution of the European Monetary Union altogether). Absent that, Greece, Portugal, Italy, yes, even Germany, functionally remain in the same position as American states, unable to create currency and therefore always subject to solvency risks which the markets may question at any time. It’s a recipe for built-in financial and political instability.

The Government of the European Union (in reality a bunch of heads of state as there is no “United States of Europe” to think of) has called the Greek government to implement all these measures in a rigorous and determined manner to effectively reduce the budgetary deficit by 4% in 2010, and “invited” the ECOFIN Council to adopt its recommendations at a meeting of the 16th of February.

It’s probably not the sort of invitation that any sovereign nation would normally accept, but Greece, like the rest of the Euro zone nations, has voluntarily chosen to enslave itself with a bunch of arbitrary rules which have no basis in economic theory. It is also being denied the use of an independent currency-issuing capacity.

This is no way for any country to achieve growth and financial stability. With no capacity to set monetary policy, fiscal policy bound by the Maastricht straitjacket, and its exchange rate fixed, the only way Greece or any of the euro zone nations can change their competitive position within the EMU is to harshly bash workers’ living conditions. That is a recipe for national suicide. And it will not reduce the deficit, because as we noted above deficits are largely determined endogenously, not by legislative fiat. The deficits reflect failing economic activity, particularly when a government is institutional constrained from implementing proactive policy to reduce output gaps left by falling private sector activity. That the measures will be imposed by an entity lacking total democratic legitimacy in Greece is only likely to exacerbate existing strains.

Why is a 4 per cent across-the-board cut being demanded of Greece? What’s the significance of that number? There is no particular budget deficit to GDP figure that is desirable or not independent of knowing about other macroeconomic settings. Just as there is no rationale provided for any of the “performance criteria” underlying the European Monetary Union’s Stability and Growth Pact. The treaty stipulated that countries seeking inclusion in the Euro zone had to fulfill amongst other things the following two requirements: (a) a debt to GDP ratio below 60 per cent, or converging towards it; and (b) a budget deficit below 3 per cent of GDP. Why 3%? Why it is 60 per cent rather than 30 or 54 or 71 or 89 or any other number that someone could write on a bit of paper? And yet we have these random numbers being used to gauge whether Greece is conducting its fiscal affairs in a proper and “responsible” manner.

This is the kind of thinking which has led to the relatively poor economic performance of many of the EU economies during the 1990s and most of the previous decade. All entrants to EMU strived to meet the stringent criteria embodied in the Stability Pact (whose principles, although largely formalized by the Maastricht Treaty in 1997, were essentially established at the beginning of the 1990s in preparation for monetary union). From 1992 to 1999, the growth of national income averaged 1.7 percent per annum in the euro-zone countries, compared with the 2.5 percent per annum averaged by the United Kingdom over the same time period. Moreover, the unemployment rate fell substantially in the United Kingdom (as well as in the United States and Canada), but tended to rise in the euro-zone countries, most notably in France and Germany.

A cavalier refusal by the EU’s technocrats to debate and address the concerns of those who feel threatened by a headlong rush into a more all-encompassing political and monetary union without adequate democratic safeguards has lent legitimacy to the views of populist politicians, such as France’s Jean Marie le Pen, and a corresponding rise of extremist parties all across the EU. This is a phenomenon that tends to arise when voters sense that their concerns are not even being considered by what they would characterize as a corrupt and cozy political class.

The EU must eliminate the underlying assumption that fiscal policy, since it can be influenced directly by the political process, should always be completely politically constrained. If anything, the performance of Euroland’s core economies over the past few years has demonstrated the total limitations of technocratic fiscal and monetary policy.

And yet this kind of deficit-bashing insanity is spreading like a cancer across the global economy. We all should know when the economy is in trouble. High unemployment; sluggish growth in output, productivity, wages; high inflation etc., these are all things which have meaning to us on an individual and collective basis. A budget deficit, by contrast, is just a number. It’s akin to blaming the thermometer when it registers that someone has a flu bug. Any doctor would legitimately be called a quack if he proposed a cure for influenza by sticking the thermometer in a bucket of ice until we got the right “reading” that was deemed to be acceptable to him.

Yet this is exactly what the poor Greeks have now been blackmailed into signing up for. Heaven help the US if it begins to move further down that road, as many are now suggesting.

*This post originally appeared on new deal 2.0.

Posted in Marshall Auerback, Uncategorized

Coherently Confronting US Macro Challenges

Many investors, policy makers, and economists find themselves unnerved by current economic conditions, and reasonably so. Depression or recovery, deflation or run away inflation, private or public insolvency – debates rage on all fronts. The disarray reflects in part the uncharted waters the global economy has sailed into over the past year, but it also reflects the inadequacy of contemporary macro frameworks. The financial balance approach is a simple yet powerful lens that can help clarify relationships that otherwise remain elusive at the macroeconomic level. Without this lens, it is hard to think coherently about the options available and their possible consequences.

We first encountered the financial balance approach[1] in the work of Wynne Godley at the Levy Institute for Economics over a decade ago, but this framework also informed the contributions of Hy Minsky and Dr. Kurt Richebacher in anticipating the conditions that give rise to financial instability at the level of the economy as a whole. It is not a difficult approach to follow, but it has proven very useful in thinking through the implications of recent credit bubbles and episodes of financial instability.

We can enter this approach from the standard macro observation that in any accounting period, total income in an economy must equal total outlays, and total saving out of income flows must equal total investment expenditures on tangible assets. The financial balance of any sector in the economy is simply income minus outlays, or its equivalent, saving minus investment. A sector may net save or run a financial surplus by spending less than it earns, or it may net deficit spend as it runs a financing deficit by earning less than it spends.

Furthermore, a net saving sector can cover its own outlays and accumulate financial liabilities issued by other sectors, while a deficit spending sector requires external financing to complete its spending plans. At the end of any accounting period, the sum of the sectoral financial balances must net to zero. Sectors in the economy that are net issuing new financial liabilities are matched by sectors willingly owning new financial assets. In macro, fortunately, it all has to add up. This is not only true of the income and expenditure sides of the equation, but also the financing side, which is rarely well integrated into macro analysis.

We can next divide the economy into three major sectors: the domestic private sector (including households and businesses), the government sector, and the foreign sector and ask a simple question relevant to current developments. What happens if the domestic private sector tries to net save, with no attending change in the government or foreign sector financial balances?

If households attempt to net save by spending less than they are earning, and businesses attempt to net save (reinvesting less than their retained earnings), then nominal incomes and real output will be likely to fall. Money incomes and economic activity will tend to contract until private savings preferences are reduced (with essential goods and services taking up a larger share of household income as incomes fall), or until depreciation leaves businesses and households inclined to invest once again in durable assets. Common sense suggests that a drop in private income flows while private debt loads are high is an invitation to debt defaults and widespread insolvencies – that is, unless creditors are generously willing to renegotiate existing debt contracts en masse.

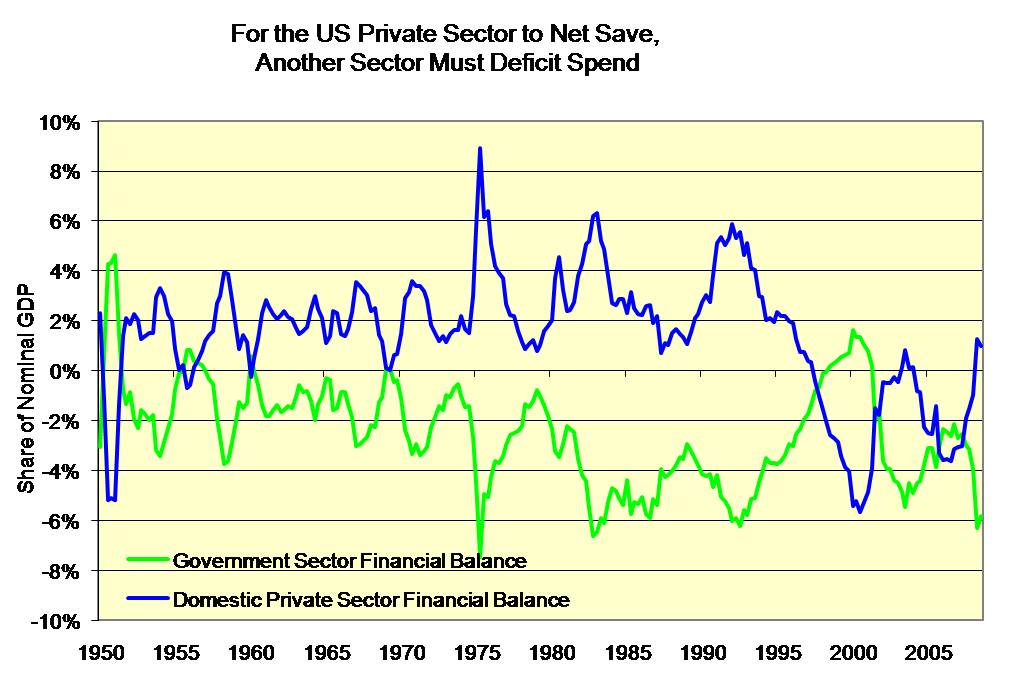

In other words, such a configuration is an invitation to Irving Fisher’s cumulative debt deflation spiral which has been discussed on this website and in prior Richebacher letters. So unless some other sector is willing to reduce its net saving (as with the foreign sector recently, via a reduction in the US current account deficit as US imports have fallen faster than US exports) or increase its deficit spending (as with the federal budget balance of late) then the mere attempt by the domestic private sector to net save out of income flows, given the existing private debt overhang, can prove very disruptive.

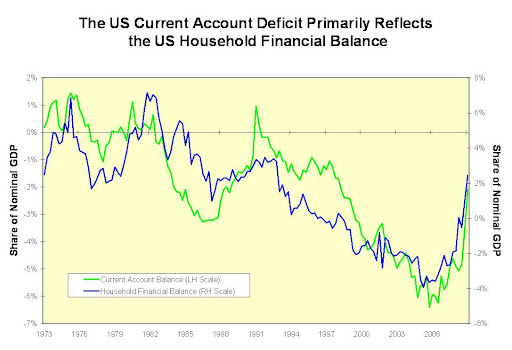

In fact, the US economy has dipped into a mild version of Fisher’s debt deflation process as nominal GDP has fallen, wage and salary income flows have fallen, the CPI and other inflation measures have dropped into deflation, and private debt delinquencies and defaults are still spreading. Following the shocks to tangible and financial asset prices, credit availability, and the labor market, the US private sector, by our calculations, has swung from a 4.5% of GDP deficit spending position three and a half years ago to a 4% net saving position as of Q1 2009. This exceeds the 8% of GDP swing in the private sector financial balance witnessed as the tail end of the 1973-5 recession – it is an enormous adjustment, to put it mildly.

Had the current account deficit (which, remember, is the trade balance plus net income flows related to asset holdings, equals foreign net saving) not shrunk from 6% to 2% of GDP over the same period, while the combined government fiscal deficit increased from 1.5% to 6% of GDP, then the attempt by the private sector to complete such a dramatic swing in its financial balance position would have ended in a very sharp and severe debt deflation.

From an Austrian School perspective, nothing less than that is required to wipe the slate clean of excess private debt and to free up productive resources misallocated during the credit boom years. However, the political appetite for an Austrian solution appears to have all but disappeared following the global repercussions of the Lehman derailment. Investors and policy makers looked into the abyss, and they could not stomach what they saw. Even Germany Chancellor Merkel, who appears to have the most Austrian orientation among G7 policymakers, has chosen to introduce some degree of fiscal stimulus and financial sector intervention in the German economy.

To further illustrate the current situation, we can use the 1973-5 recession as a rough guide – after all, as mentioned above, that is when domestic private net saving jumped to its highest share of GDP in the post WWII period. Currently, we appear to have an even deeper recession, and we know the drop in the ratio of household net worth to disposable income is over four times that experienced in the 1973-5 episode. What happens if private net saving preferences run all the way up to 10% of GDP, with say an additional 4% of GDP increase from the household side, and another 2% from the business side?

If the swing evident from 2006 is any indication, the hypothetical 4% increase in the household financial balance as a share of GDP will take the current account back to balance (for the first time in nearly two decades) from its recent 2% of GDP deficit position. To further contain debt deflation dynamics, given a domestic private sector attempting to save 10% of GDP, the combined fiscal balance will need to expand out to 10% of GDP, or else private income will fall further. The reduction in foreign net saving and the increase in fiscal deficit spending will then match the increase in private net saving from Q1 2009 values assumed above.

If the combined government deficit aims for 12-13% of GDP while the domestic private sector is shooting for 10% and net foreign saving is zero, then the odds improve that an economic recovery can take root alongside a larger private sector deleveraging than we witnessed in Q1 2009. Household and business incomes will be buttressed by tax cuts and government spending, which will allow higher private spending for any given private saving target. In other words, in a worst case scenario, it does appear debt deflation dynamics can be contained and reversed, but at the price of a rather large fiscal deficit that in essence validates higher domestic private sector net saving. The linkages between rising private sector net saving and deflation, and between fiscal deficits and private net saving, are currently poorly understood, but the financial balance approach helps bring some clarity to these questions.

Normally, the business sector tends toward a deficit spending position as profitable investment opportunities exceed retained earnings. This makes a certain amount of sense: debt imposes future cash flow commitments on borrowers, and using debt to expand productive capacity allows the borrower to have a decent shot at generating sufficient cash flow to service debt. Notice this is not usually the case with consumer debt, except perhaps with the case of mortgages used to purchase rental properties, or credit cards used to finance new small businesses. Households do not directly increase their income earning capacity, and hence their debt servicing capacity, by purchasing a flat screen TV or a larger house on credit. Of course, businesses that use credit to buy back shares or complete a merger or acquisition similarly are not directly enhancing their ability to service debt with new productive capacity, so the intended use of new debt is relevant in either sector.

Richard Koo makes the related point in his book, “The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics”, that following the bursting of an asset bubble, businesses often move into a debt reduction mode that takes over their usual search for profitable opportunities. For the current post bubble period, reeling fiscal deficit spending back in before the business sector is headed back toward its more “natural” deficit spending position, or before the rest of the world has found its way to a faster pace of recovery than the US (thereby aiding US export growth), could prove disruptive.

Ideally then, fiscal deficit spending would be designed to encourage businesses to reinvest in more efficient technology or in new product innovation, both of which could help improve US export competitiveness. Alternatively, public/private cooperation in R&D projects like Sematech could be explored with various emerging energy technologies, for example, in order to reduce US energy dependence. Such moves would speed the transition away from deep fiscal deficit spending which began riling investors in longer dated Treasury debt back in March. Nevertheless, such a shift in the fiscal deficit was required for the domestic private sector to return to a net saving position and begin reducing its debt load without setting off a full blown debt deflation.