By Glenn Stehle

Money and art, in the minds of some, are now one and the same.

Izabella Kaminska, for example, recently asserted that art is “the sophisticated man’s Bitcoin.” It is the “safe store-of-value” which “art aspires to that is our intended meaning,” she avers. “Think sophisticated man’s Bitcoin rather than asset class outright.”

Kaminska goes on to elaborate that much art

is being ‘mined’ purely to satisfy the demand for ‘safe-ish’ assets in a liquidity saturated world. Safe assets, which we should add, are often held in bonded warehouses in places like Geneva, outside of the reach of tax authorities, and which later become a type of bearer security in their own right as the depository receipts which allow redemption of the assets begin to circle amongst the wealthy as their own type of non-taxable currency.

Much of the value of art, according to Kaminska, is just like that of Bitcoins. It depends on the “the Emperor’s New Clothes effect. “If we — art dealers, collectors, writers and experts – all agree a particular work has value,” she asserts, “it surely does, irrespective of its costs of production, utility and purpose.”

Scarcity, adds Kaminska, is another requirement of Bitcoins and art to be viable currencies. But “art, unlike Bitcoin and gold, is not scarce.” The problem of scarcity, however, is solved by the regulation of art supply by “the tight and clubby world of the art dealer and auctioneer network.” The world of art marketing is “very similar to venture capital, insofar as who you know matters.” And just as with central bankers, who choose “to support a particular type of asset-backed security or not, which lacking central bank support might otherwise crash in value,” it is art dealers’ asset purchases which “dictate the market.”

But art has another pillar of value, Kaminska concludes, other than just “the closed and networked nature of salon society.” And that, she argues, is art’s “creative and visionary expression.” The new, the original and the didactic, according to the devotees of conceptual art like Kaminska, are all that are needed to make a great piece of art. The concept(s) or idea(s) involved in the work take precedence over traditional aesthetic and material concerns. “True creativity endures as one of the last eternal scarcities,” Kaminska gushes.

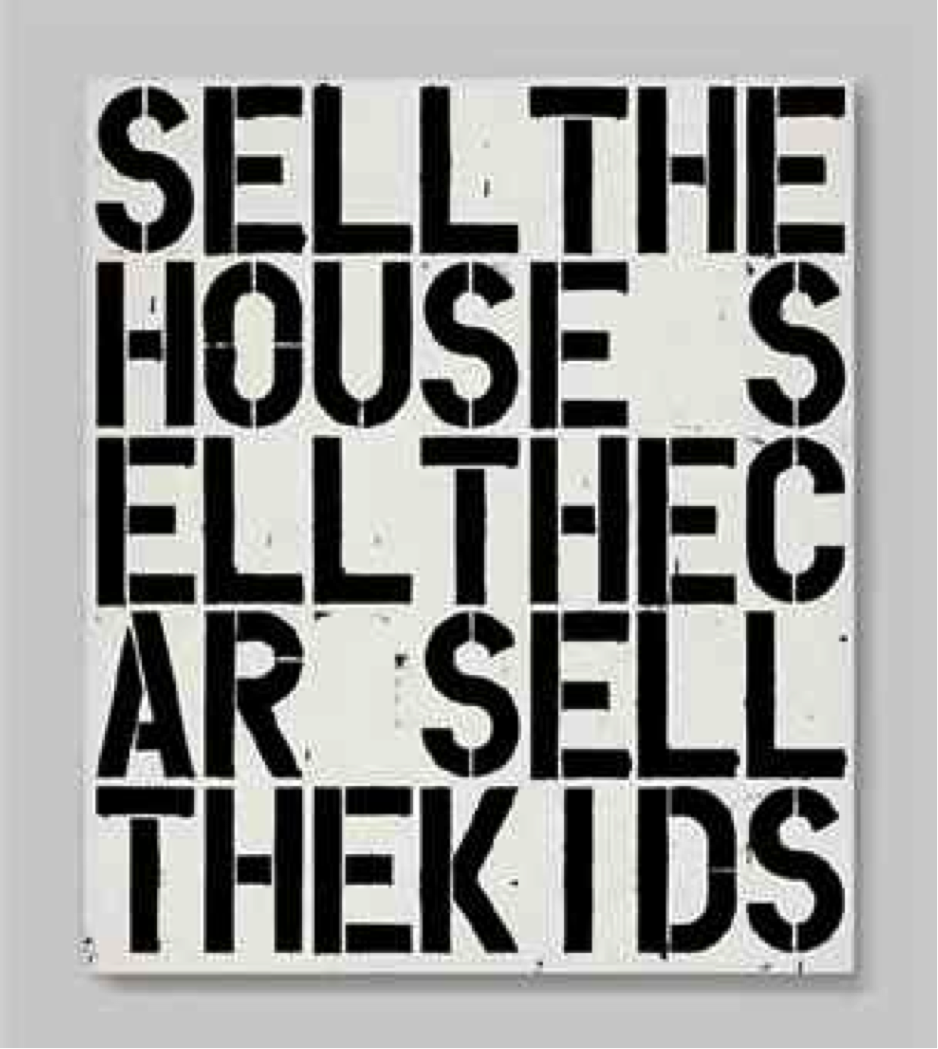

So just for fun, let’s take a look at a couple of examples of the “true creativity” which Kaminska argues may constitute “a true Renaissance effect.” The first is a painting by the mid-career artist Christopher Wool. It fetched a whopping $26.4 million at auction last month. “The painting, Apocalypse Now, is one of Wool’s early word works, this one emblazoned with a line from the Francis Ford Coppola movie: ‘SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS.’” (Jed Perl, “The Super-Rich are Ruining Art for the Rest of Us” ).

But Wool is small potatoes. And it is not Wool, but the London-based artist Damien Hirst, who is the Joan of Arc of the new consciousness of art. It is he, after all, who has become symbolic of

the unstoppable rise of art as commodity and the successful artist as a brand; the ascendancy of a post-Thatcher generation of Young British Artists (YBAs) who set out, unapologetically, to make shock-art that also made money….

—SEAN O’HAGAN, “Damien Hirst: ‘I still believe art is more powerful than money’”

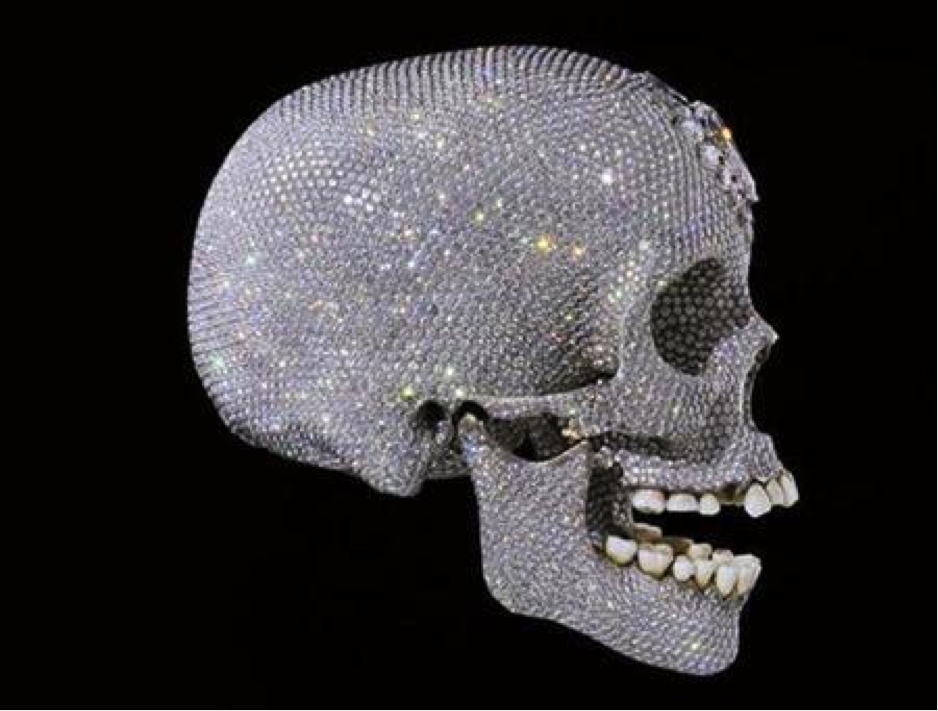

In 2007, Hirst sold a diamond-encrusted platinum skull to an investment group for $100 million ( Jeremy Lovel, “Hirst’s Diamond Skull Sells for $100 million”). One wonders, however, where the “creative and visionary expression” is if this is being billed as conceptual art, because Mesoamerican artists were making skulls encrusted with precious stones over 500 years ago. And there is no great technical skill or virtuosity involved on Hirst’s part, because Hirst’s creations are not crafted by him, but by the many employees who work in his atelier.

Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted platinum skull sold to an investment group in 2007 for $100 million

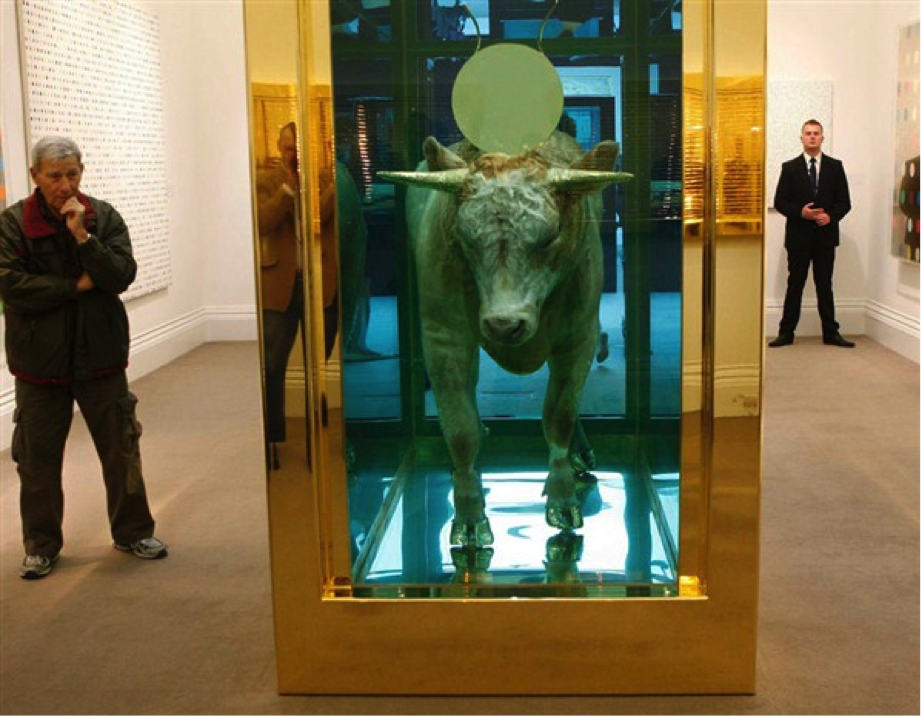

Then in 2008 Hirst sold The Golden Calf, an animal with 18-carat gold horns and hooves, preserved in formaldehyde, in a one-man sale at Sotheby’s that brought in a total of $200.7 million (Carol Vogel, “Bull Market for Hirst in Sotheby’s Two-day Sale”)

The Golden Calf by Damien Hirst sold at Sotheby’s in 2008 in a one-man auction that brought a total of $200.7 million

“I think art’s the greatest currency in the world. Gold, diamonds, art — I think they are equal. … I think it’s a great thing to invest in,” opined Hirst ( “Art is ‘world’s greatest currency,’ says Damien Hirst” ). It’s “been hard to see the art for the dollar signs,” Hirst admits. “Money is massive. I don’t think it should ever be the goal, but I had no money as a kid and so I was maybe a bit more motivated than the rest. I used to argue with Angus [Fairhurst] and Sarah [Lucas] about that all the time when we were starting out and struggling. They’d say: ‘You’re obsessed’ and I’d be like, ‘It’s important.’ See, if you don’t care about it, often you don’t deal with it, then it screws you” ( Sean O’Hagan, “Damien Hirst: ‘I still believe art is more powerful than money’”).

But there’s another thing about art which qualifies it as money which neither Kaminska nor Hirst mention. And that is that in some countries art can be used to satisfy tax liabilities. In Mexico, for instance, plastic artists can pay their taxes with their own creations in a program called pago en especie (Fernando Franco, “The Art of Paying Taxes,” Excelsior, August 1, 2011). And in the United States the tax man has become the world’s most generous art patron. “An American invention, the tax deduction for charitable contributions assures an astonishing diversity of philanthropic endeavors,” notes Alice Goldfarb Marquis in Art Lessons. “While publicity, self-promotion, and the chance to gain the ear of the influential frequently motivate benefactors, the American tax system guarantees their continuing generosity.” In 2006 U.S. individual taxpayers claimed itemized deductions for charitable contributions of art and collectibles worth more than $1.22 billion (Alan Breus, “Valuing Art for Tax Purposes”).

On the other side of the ideological divide

Not everyone who entertains the notion that art equals money is as sanguine about art’s value, however, as Hirst and Kaminska. Standing on the other side of the ideological and artistic Grand Canyon we find David Harvey.

Harvey, I perceive, is one of those people like Michael Hudson who has, as Benjamin Kunkel puts it, found “a convergence of Keynesian and Marxian views” (Benjamin Kunkel, “How Much Is Too Much?”). The runaway art market, seen from Harvey’s Marxist-Keynesian perspective, is a manifestation of yet one more crisis of capitalism.

“Credit can be used to accelerate production and consumption,” Kunkel explains. But unfortunately this happy balance between “the amount of total social income to be reinvested in production and the amount to be spent on consumption” is seldom struck, “except occasionally and by accident, to be immediately upset by any advantage gained by labour or more likely by capital.” When this ideal proportion between the “opposing pursuits of profits and wages” is upset, as it almost always is because of the internal contradictions built into capitalism, the result is the overaccumulation of one of several types of capital. In the current crisis, there is an overaccumulation of fictitious capital, which is “credit or bank money” which is described as being “money values backed by tomorrow’s as yet unproduced goods and services.” Credit can co-ordinate the flow of economic value, but can’t create it ex nihilo: “There is no substitute for the actual transformation of nature through the concrete production of use values.” Because of “impaired profitability” in “further investment in production” this surfeit of fictitious capital has “turned increasingly to speculation in asset values,” including art. Kunkel elaborates as follows:

Joseph Stiglitz observed that the savings glut ‘could equally well be described as an “investment dearth”’, reflecting a scarcity of attractive investment opportunities….

The neo-Keynesians’ ‘savings glut’ can readily be seen as a case of what a more radical tradition calls overaccumulated capital. But it is the broader and more systematic Marxist perspective that ultimately and properly contains Keynesianism within it, and a crude Marxist catechism may be in order. Where does an excess of savings come from? From unpaid labour – for example, that of Chinese or German workers. And why would such funds inflate asset bubbles rather than create useful investment? Because capital pursues not ‘high social returns’, but high private returns. And why should these have proved difficult to achieve, except by financial shell-games? Keynesians complain of an insufficiency of aggregate demand, restraining investment. The Marxist will simply add that this bespeaks inadequate wages, in the index of a class struggle going the way of owners rather than workers.

In The Enigma of Capital Harvey asserts that our current crisis is a sequel to a profit crisis which reached acute proportions in the early 1970s. The causes of the profit crisis are disputed. But as Christian Parenti observes in Lockdown America: “Regardless of the exact etiology of the profit slump, one thing is for sure, the solution to the crisis was…to attack labor.”

Kunkel summarizes Harvey’s take as follows: “a subsequent effort to curb wages, carried out at gunpoint in the Southern Cone in the mid-1970s, and achieved by ballot under Thatcher and Reagan before spreading to other wealthy countries…eventually resulted in a systemic shortage of demand… In The Enigma of Capital, Harvey charts the dialectical switch in the blunt style he now favours:

Labour availability is no problem now for capital, and it has not been for the last 25 years. But disempowered labour means low wages, and impoverished workers do not constitute a vibrant market. Persistent wage repression therefore poses the problem of lack of demand for the expanding output of capitalist corporations. One barrier to capital accumulation – the labour question – is overcome at the expense of creating another – lack of a market. So how could this second barrier be circumvented?

“The lack of demand was of course appeased by recourse to fictitious capital,” Kunkel continues. “‘The gap between what labour was earning and what it could spend was covered by the rise of the credit card industry and increasing indebtedness.’” So the world was subsumed in an overaccumulaiton of fictitious capital: “money that is thrown into circulation as capital without any material basis in commodities or productive activity” to repay it.

In Harvey’s essay “The art of rent: Globalization, monopoly and the commodification of culture” he connects the overaccumulation of fictitious capital to what is transpiring in the art market and indeed the overall world of art. It is here we find the truly original part of Harvey’s thought. Harvey connects art and capital via a theory of rent.

Harvey posits that the “expansion of capitalism is…to be interpreted as capital in search for surplus value.” This explains the “penetration of capitalist relations into all sectors of the economy.” Hence both the involution and the imperialism of capital, commidifying the most intimate of formerly uncommodified practices (art, culture, courtship) as well as sweeping formerly non-capitalist regions into the global market.

According to Harvey, it is the quest for “monopoly rent” where the “nexus between capitalist globalization, local political-economic developments and the evolution of cultural meanings and aesthetic values” is to be found. As he explains:

Monopoly rent arises because social actors can realize an enhanced income stream over an extended time by virtue of their exclusive control over some directly or indirectly tradable item which is in some crucial respects unique and non-replicable…. [In some cases the] resource is directly traded upon (as when vineyards or prime real estate sites are sold to multinational capitalists and financiers for speculative purposes). Scarcity can be created by withholding the land or resource from current uses and speculating on future values. Monopoly rent of this sort can be extended to ownership of works of art (such as a Rodin or a Picasso) which can be (and increasingly are) bought and sold as investments. It is the uniqueness of the Picasso or the site which here forms the basis for the monopoly price.

Harvey goes on to explain “that the idea of ‘culture’ is more and more entangled with attempts to reassert such monopoly powers precisely because claims to uniqueness and authenticity can best be articulated as distinctive and non-replicable cultural claims.” But there are some rubs:

1) The bland homogeneity that goes with the pure commodification erases monopoly advantages. Cultural products become no different from commodities in general as “commodity aesthetics extends its border further and further into the realm of cultural industries.”

2) Monopoly claims are as much ‘an effect of discourse’ and an outcome of struggle as they are a reflection of the qualities of the product.

3) A considerable amount of the current interest in cultural innovation and the resurrection and invention of cultural traditions attaches to the desire to extract and appropriate rents. Or as Alice Goldfarb Marquis puts it in Art Lessons: “At the ‘meat market,’ the arts in America, in all their boisterous complexity and diversity, once more confound the holiness of the art religion with the base scrabble of cold cash.”

Harvey uses the wine trade as an example of how the quest for monopoly rents has penetrated the cultural arena:

The wine trade is about money and profit but it is also about culture in all of its senses (from the culture of the product to the cultural practices that surround its consumption and the cultural capital that can evolve alongside among both producers and consumers). The perpetual search for monopoly rents entails seeking out criteria of speciality, uniqueness, originality and authenticity in each of these realms. If uniqueness cannot be established by appeal to ‘terroir’ and tradition, or by straight description of flavour, then other modes of distinction must be invoked to establish monopoly claims and discourses devised to guarantee the truth of those claims (the wine that guarantees seduction or the wine that goes with nostalgia and the log fire, are current advertising tropes in the US). In practice what we find within the wine trade is a host of competing discourses, all with different truth claims about the uniqueness of the product. But, and here I go back to my starting point, all of these discursive shifts and swayings, as well as many of the shifts and turns that have occurred in the strategies for commanding the international market in wine, have at their root not only the search for profit but also the search for monopoly rents. In this the language of authenticity, originality, uniqueness, and special unreplicable qualities looms large. The generality of a globalized market produces, in a manner consistent with the second contradiction I earlier identified, a powerful force seeking to guarantee not only the continuing monopoly privileges of private property but the monopoly rents that derive from depicting commodities as incomparable.

Returning to the plastic arts, one of the challenges has always been how to insure the authenticity of the commodity. “More generally, to the degree that such items or events are easily marketable (and subject to replication by forgeries, fakes, imitations or simulacra) the less they provide a basis for monopoly rent,” notes Harvey. Which brings us back to Kaminska’s claim: “If we — art dealers, collectors, writers and experts – all agree a particular work has value, it surely does.” But again there’s a rub: Experience has repeatedly demonstrated that this assorted lot of tony gatekeepers is not very adept at discriminating fact from fiction.

La Falsificación Y Sus Espejos (Falsification and Its Mirrors) delves into this soft underbelly of the art world. The tales of those who have fooled the art world’s lofty and erudite beautiful people are legion. They range from the 20th century’s greatest (known) forger, Hans van Meegeren, to Brígido Lara Lara, who says he created maybe 40,000 pieces of forged pre-Columbian pottery. These forgeries fooled the greatest museum curators, collectors, and art dealers in the world, including those at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, and Sotheby’s (La Falsificación Y Sus Espejos). “A case in point is the three-foot-tall hollow clay bust of the central Mexican wind god, Ehecatl, that was once displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” writes Mimi Crossley. “When he was shown a photograph of the curl-snouted statue, Lara said, ‘This one I invented completely. A piece like this has never been excavated, and all those in existence are mine.’ Even so, scholars of pre-Columbian art have been studying and writing about the Metropolitan’s wind god for years.” The late Nelson Rockefeller bought the bust Ehecatl from a dealer in the United States in 1957.

Brígido Lara Lara, shown with one of his “pre-Hispanic” pottery creations that fooled all the world’s greatest art experts

All of this goes to highlight the frailty of the human enterprise. It is well worth remembering what Alberto Ruy-Sánchez wrote in his introduction to La Falsificación Y Sus Espejos:

[F]orgery constitutes a sort of novel describing the human comedy, as fascinating as it is revealing of our most elemental impulses. Forgery points its accusing finger at us, reminding us that we are essentially primitive mimetic animals. Forgery pertains to the genre of the tragicomedy: it is the mise-en-scène of a delusion that ridicules us as it reveals the fragile nature regarding our notions of truth, authentic and belief. The world of money and prestige linked to art dreads forgery as a menace to its workings. While approaching through the weak side of the obese art market, this issue aims to show that forgery is a more meaningful phenomenon rooted in our instincts. The relationship between art and truth is not an easy one…including the famous riposte by Diego Rivera upon discovering that many pieces in his collection of pre-Hispanic art were recently-made fakes (“Same Indians, same clay”). It also includes the story of a man [Brígido Lara Lara] imprisoned for trafficking ancient pieces who, in order to secure his release, is forced to demonstrate that in fact it was he who made them – patina and all. Paradoxically, it is the authentic of his forgeries which eventually set him free. Closer to our time is the case of a young but prestigious artist who – despite the expert opinions – claims that a painting attributed to him, purchased in New York, is a forgery. The sale is aborted and the piece is determined a fake. Some time later, he confesses to the buyers that the work is actually authentic but that it had been stolen from his studio some years earlier and that he had no intention of letting anyone profit from that painting. In this way, a painter managed to forge his own fake. The mirror play is infinite and all-inclusive. It is a manifold labyrinth in which we intuit the fragility of our steps.

“Capitalists are well-aware of this,” Harvey observes, but nevertheless must wade into the culture wars and the thickets of aesthetics “because it is precisely through such means that monopoly rents stand to be gained.” “And if, as I claim,” Harvey continues, “monopoly rent is always an object of capitalist desire, then the means of gaining it through interventions in the field of culture, history, heritage, aesthetics and meanings must necessarily be of great import for capitalists of any sort. The question then arises as to how these cultural interventions can themselves become a potent weapon of class struggle.”

This raises the image of Neil Smiths “revanchist city.” As Tom Slater explains:

Smith identified a striking similarity between the revanchism of late 19th century Paris and the political climate of late 20th century New York City that emerged to fill the vacuum left by the disintegration of liberal urban policy. He coined the concept of the revanchist city to capture the disturbing urban condition created by a seismic political shift: whereas the liberal era of the post-1960s period was characterized by redistributive policy, affirmative action and antipoverty legislation, the era of neoliberal revanchism was characterised by a discourse of revenge against…the ‘public enemies’ of the bourgeois political elite and their supporters.

Marshall Berman, on his visit to Lodz last year, was taken aback by Manufaktura. The monumental old Poznanski factory had been converted into the biggest shopping center in Europe. It no longer houses machines, but stores, restaurants, movie theaters, museums and a hotel, while the former workers have been relegated to structural unemployment and can’t even afford the price of a cappuccino in this “new capitalist culture.” (Maceik Wisniewski, “Marshall Berman y el urbicidio capitalista”)

As Harvey concludes:

At the very minimum this means resistance to the idea that authenticity, creativity and originality are an exclusive product of bourgeois rather than working class, peasant or other non-capitalistic historical geographies, and that they are there merely to create a more fertile terrain from which monopoly rents can be extracted by those who have both the power and the compulsive inclination to do so. It also entails trying to persuade contemporary cultural producers to redirect their anger towards commodification, market domination and the capitalistic system more generally. It is, for example, one thing to be transgressive about sexuality, religion, social mores and artistic conventions, but quite another to be transgressive in relation to the institutions and practices of capitalist domination.

And here we are presented with yet one more enigma of the crazy, upside down world of art. For even though Damien Hirst was born into the working class, he somehow managed to escape it, yet seems to have no connections whatsoever to that life or the people he left behind.

2 responses to “Of art and money, Bitcoins and Damien Hirst”