Some like to see green shoots everywhere, but that is becoming an increasingly audacious hope. Here are four related stories from the July 5th edition of the New York Times:

Tax Bill Appeals Take Rising Toll on Governments By JACK HEALY

Homeowners across the country are challenging their property tax bills in droves as the value of their homes drop, threatening local governments with another big drain on their budgets…. The tax appeals and reassessments present a new budget nightmare for governments. In a survey conducted by the National Association of Counties, 76 percent of large counties said that falling property tax revenue was significantly affecting their budgets…. Officials in some states say their property tax revenue is falling for the first time since World War II.

Safety Net Is Fraying for the Very Poor By ERIK ECKHOLM

Government “safety net” programs like Social Security and food stamps have pulled growing numbers of Americans out of poverty since the mid-1990s. But even before the current recession, these programs were providing less help to the most desperately poor, mainly nonworking families with children… The recession is expected to raise poverty rates, economists agree, although the impact is being softened by the federal stimulus package adopted this year…. “It’s a good thing we have the stimulus package,” Mr. {Arloc} Sherman said. “But what happens to the most vulnerable families in two years, when most of the provisions expire?”

Employment Report Sours the Market By JEFF SOMMER

A grim report on unemployment on Thursday let the air out of the stock market…. In a monthly report, the Labor Department said that 467,000 jobs were lost in June. In surveys, most economists expected 100,000 fewer jobs lost. The unemployment rate edged up to 9.5 percent from 9.4 percent the previous month, to its highest level in 26 years, and virtually all analysts expect joblessness to mount in the coming months.

So Many Foreclosures, So Little Logic By GRETCHEN MORGENSON

LAST week, the stock market tumbled on news that housing foreclosures and delinquencies rose again in the first quarter. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency said that among the 34 million loans it tracks, foreclosures in progress rose 22 percent, to 844,389. That figure was 73 percent higher than in the same period last year…. But the most fascinating, and frightening, figures in the data detail how much money is lost when foreclosed homes are sold. In June, the data show almost 32,000 liquidation sales; the average loss on those was 64.7 percent of the original loan balance.

What do these reports have in common? They provide powerful evidence that the federal government is not doing enough to help the “real” economy. As Sam Gompers famously responded when asked what workers wanted–“More!”—our nation’s state and local governments, households, workers, and poor need more help, now. We have tried the Reagan/Paulson/Rubin/Geithner “trickle down” approach of targeting relief to Wall Street, but the only thing trickling down is misery. The only way to stop the downward spiral is to substitute trickle-up policy—and even if nothing trickles-up, at least we will have helped those most in need.

I have already outlined a comprehensive recovery package so will here simply summarize four policies that would bring immediate relief.

1. Payroll tax holiday: This provides nearly $2500 of tax relief per year for each worker, with the same amount of relief going to that worker’s employer. The total stimulus to the economy would be somewhere around $650 billion per year. The relief is well-targeted (to workers and employers), immediate (take home pay rises as soon as the holiday takes effect), simple to administrate, and can be phased out (if desired) after the economy recovers.

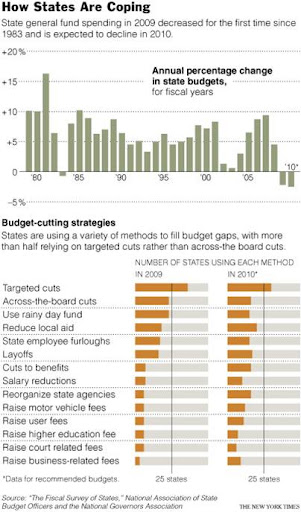

2. State and local government assistance: The current stimulus package provided some relief to state and local governments, but was so little that it is forcing them to make Hobson’s choices: cut poor children from Medicaid roles or decimate universities? Furloughs for firefighters or postpone bridge repairs? Increase real estate taxes or raise fees for services? Only the federal government can resolve revenue shortfalls by providing funding to keep state and local governments running. Perhaps $400 billion, allocated by population (a bit over $1200 per capita) across state and local governments would be sufficient. If President Obama really could reform healthcare, that would generate tremendous savings for state governments that are saddled with exploding Medicaid costs to cover low income and elderly patients. Until then, direct grants are required. As I have argued, for the long-term we need a permanent program of federal transfers to states, with some of that attached to a requirement that they reduce reliance on regressive taxes.

3. Jobs to reduce poverty: Last week Pavlina Tcherneva provided an excellent argument for direct job creation by the federal government. We have already lost 6 million jobs, and Tcherneva notes that unemployed plus discouraged workers total about twice that number. However, a plausible case can be made that we are short more than 20 million jobs—as Marc Andre Pigeon and I demonstrated a decade ago. Further, as Stephanie Kelton and I showed, a substantial amount of America’s poverty problem is really a jobless problem. We found that in 2002 the poverty rate of families with no member working reached nearly 26%; on the other hand, if the family had at least one member working full-time, the poverty rate fell to just 3.5%. Our conclusions were similar to those offered by Hyman Minsky: “The achievement and sustaining of tight full employment could do almost all of the job of eliminating poverty” (1968, p. 329); “a large portion of those living in poverty and an even larger portion of those living close to poverty do so because of the meager income they receive from work” (p. 328). Minsky believed that “a suggestion of real merit is that the government become an employer of last resort” (1968, p. 338). Thus, not only will direct job creation reverse the trend toward ever-higher unemployment rates, but it will also go a long way toward filling the growing holes in the social safety net.

4. Homeowner relief: The plan offered by Warren Mosler provides an alternative to the current painful foreclosure process. When banks begin to foreclose, the government would step in to purchase the property at the lower of market price or outstanding mortgage balance. Of course, establishing market price in a glut is not simple and I will leave it to real estate market experts to compose a plan. What is more important is to keep people in their homes. Mosler proposes that the federal government would rent homes back to the dispossessed owners (Dean Baker has a similar plan) for a specified period (perhaps two years) at fair market rent. At the end of that period, the government would sell the home, with the occupant having the right of first refusal to buy it. By itself, this proposal would do little to stop spiraling delinquencies and foreclosures, and home prices will probably continue to decline for many months (or even years). However, as the other parts of this stimulus package begin to spur recovery, the real estate sector freefall will (eventually) be halted. I am somewhat ambivalent about continued falling house prices—on one hand, this will make housing more affordable; on the other it is devastating for families. Still, reducing evictions by offering a rental alternative will help reduce the pain of foreclosure. It might also allow the process to speed up (with smaller losses for banks) since many families would choose to stay-on as renters, with the possibility that they could later buy their homes at more reasonable prices.

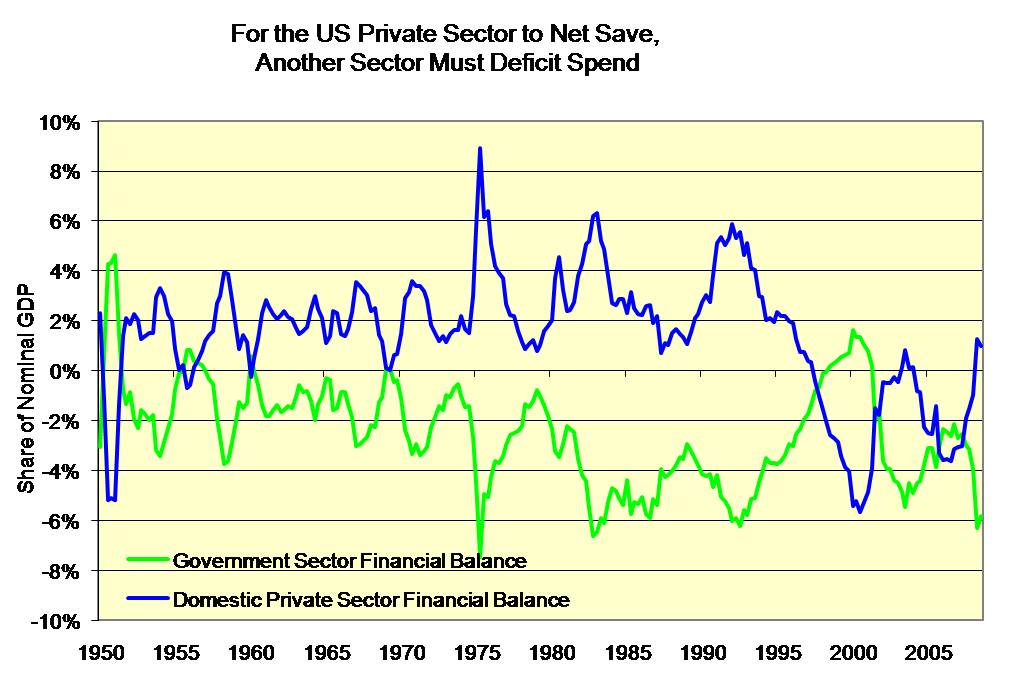

I will not address here the preposterous argument that failure of the economy to swiftly recover is evidence against the Keynesian belief that government spending is the answer. Leaving to the side the Wall Street bail-outs (that do little to stimulate production and jobs), only a small portion of the stimulus package has been spent to date. There is evidence, however, that the automatic stabilizers (falling federal tax revenue and rising federal spending) are doing some good already—and would eventually pull the economy out of this depression. However, there is no reason to wait for our ship to hit bottom before it slowly resurfaces. Active, discretionary, targeted policy can reduce suffering and generate the forces that will be required to overcome substantial headwinds created by the private sector as well as by our state and local governments. Only the federal government has the fiscal wherewithal to lead us out.

To deal with these shortfalls, states have laid off or furloughed thousands of employees, raised taxes and fees, and slashed spending on education and other social programs – some, many times over. It was supposed to balance their ’09 budgets. But it wasn’t nearly enough.

To deal with these shortfalls, states have laid off or furloughed thousands of employees, raised taxes and fees, and slashed spending on education and other social programs – some, many times over. It was supposed to balance their ’09 budgets. But it wasn’t nearly enough.