By Scott Fullwiler

My previous post critiquing Scott Sumner’s (and others’) proposal for negative nominal interest rates brought a most welcome response from Prof. Sumner in the comments section. The comments section has a character limit that I’m sure to go over in response to his response, however; hence this post. The core of my reply and critique here is twofold: first, Sumner misunderstands the Fed’s monetary operations, particularly the details of reserve accounting (that is, the dynamics of changes to the Fed’s balance sheet); and second, the proposal assumes the textbook money multiplier when in fact this doesn’t apply to the U.S. or any other nation not operating under a fixed exchange rate policy such as a gold standard or currency board.

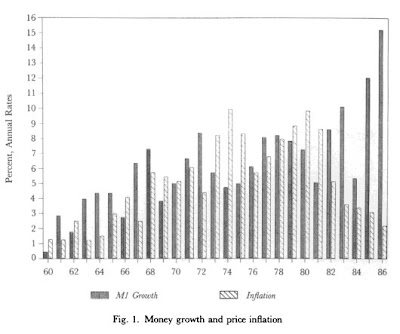

Sumner’s original proposal, as he notes in the comments, can be found here. The basics of the proposal are that the Fed would set a modestly negative rate to be paid on bank excess reserves (ERs; he has discussed rates -2% and -4% on his blog); given this penalty, banks would then be encouraged via the monetarist “excess cash balance” mechanism, as he describes it (i.e., the money multiplier) to create deposits that would thereby transform these ERs into required reserves that would not be subject to the penalty. The problem the proposal supposedly solves is that banks are “sitting” on their excess balances (currently around $700 billion) and need an incentive to “move [ERs] into cash in circulation.”

Turning to reserve accounting, consider Sumner’s comment on my original post:”The proposal would not drive interbank loan rates significantly negative, as banks could always exchange ERs for T-bills. And T-bill yields could not go significantly negative because non-bank holders of T-bills can always hold cash.”

As a small aside, I’m puzzled why he would think my critique centered on the interbank rate or T-Bill rate, as my critique was instead directed at the “excess cash balance” mechanism or money multiplier; that these rates might turn negative is not necessarily problematic in my opinion, but that’s what will happen, so I noted as much. But I digress.

Sumner’s statement “banks could always exchange ERs for T-bills” misses an important point . . . namely because this transaction would not extinguish the reserve balances, but rather move them to the (in the case of a non-bank seller) seller’s bank. So, let’s assume that the seller’s bank had no undesired ERs prior to the sale. Now, after the sale, it DOES have undesired ERs (while, yes, the non-bank seller can now hold deposits or CDs or whatever).

The fundamental point here is that ONLY changes to the Fed’s balance sheet can change the aggregate quantity of reserve balances held by banks. In other words, the Fed is the MONOPOLY supplier of net reserve balances to the banking system. This is not an opinion or a theory, but rather a FACT of double-entry reserve accounting . . . aggregate reserve balances are on the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet, only a change somewhere else on the Fed’s balance sheet can alter them. And the T-bill purchase Sumner describes does not involve the Fed’s balance sheet.

In fact, the only way a T-bill purchase would extinguish reserve balances as Sumner proposes is if the purchase is done at auction (from his quote, clearly not what he was intending), which would in fact be a roundabout way of having the Fed simply add balances to the Treasury’s account (again, I’ll assume he wasn’t intending this with his proposal).

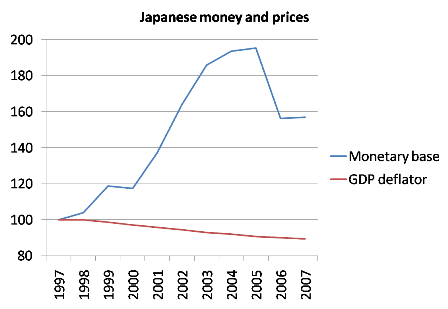

So, if we have an aggregate banking system with some undesired excess balances, the banks individually can trade these among themselves however they want (fed funds market, T-bill transactions, repos, and so forth), but the undesired excess simply moves from bank to bank, never going away. It’s well established in the academic literature on the fed funds market that this brings the fed funds rate down toward the level paid to banks on reserve balances (which Sumner’s wants negative). Hopefully it’s clear, though, that my criticism in this case is not and was not about the fact that the interbank rate would fall, but rather about the inherent misunderstanding of reserve accounting in the proposal (and, alas, in Sumner’s comment above).Very briefly to his point on T-bill rates, any individual bank will purchase T-bills at yields higher than its marginal return on ERs at the Fed. These purchases move those reserves to other member banks, which then do the same, thereby driving T-bill rates down to or even below the Fed funds rate. Furthermore, negative T-bill rates have for technical reasons in fact been a common occurrence in both Japan and the U.S.

For a little more detail, consider Sumner’s following comment from his original proposal: “We also know that banks hold very low levels of ERs any time the opportunity cost (in terms of the T-bill alternative) is even modestly positive. Thus in the summer of 2008 when the target rate was only 2%, ERs were still very low.”

Wrong. Banks DESIRE to hold low levels of ERs when the opportunity cost is even modestly positive. But they will by definition in the aggregate hold as many as the Fed leaves circulating, since the Fed is the monopoly supplier of aggregate reserve balances. Prior to September 2008, the Fed ACCOMMODATED banks’ desire to hold low levels of ERs by draining any additional balances via reverse repos and such—a process that had become very complicated starting in August 2007 (but that’s a long story in itself). Virtually every other central bank does the same under normal circumstances.

After September 2008, circumstances were not normal, as the Fed (in its view, at least) no longer had enough purchased assets to sell or repo to drain any undesired ERs created via its various standing facilities. Consequently, while banks individually actually may have DESIRED to hold lower levels of ERs (though their desired quantity was admittedly increased above normal given substantial concerns about counterparty risks), in the aggregate, they had no choice but to hold a larger quantity (again, though, the Fed’s repeated flubs with instituting payment on reserve balances kept the fed funds rate well below the target and thereby minimized any opportunity cost that might have existed).

I don’t want to dwell on this particular point too much, as it moves a bit too far ahead given that, for Sumner’s proposal, at issue isn’t the aggregate quantity of reserve balances but rather how to transform the ERs to required reserves. But clarity on reserve accounting in monetary operations is absolutely essential, as we’ll see again below.

As for transforming the ERs to required reserves, Sumner writes in his original post that “from a monetarist excess cash balance perspective, the problem is the hoarding of ERs by banks.” So, now quoting from his comments on my post, his excess reserve tax proposal is intended “to move ERs into cash in circulation . . . [as it] . . . relies on the monetarist ‘excess cash balance’ mechanism.” From his original post, “a penalty rate on ERs of say 4% should bring ERs down to extremely low levels.”

That is, penalizing banks for holding ERs is proposed in order to encourage banks to create more deposits, thus raising reserve requirements and lowering the relative quantity of ERs among existing reserve balances.

This is the money multiplier framework, which is inapplicable to the US monetary system, as noted above. So what this errant view does is cause Sumner to get the problem wrong.

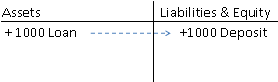

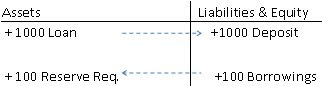

To see why, consider a bank with no ERs at all. Suppose a credit worthy customer comes through the door and wants a loan and the bank deems the loan profitable. Does the bank have the operational ability to create the loan? In EVERY country not operating under a fixed exchange rate system such as a gold standard or a currency board, the answer is YES. As I have explained in previous posts (here and here), if the bank ends up short on its reserve requirements, it incurs an overdraft automatically from the Fed at a stated penalty rate as a matter of accounting. In practice, this wouldn’t actually occur for at least 2.5 weeks given lagged reserve accounting in the US, by which time the bank’s liquidity manager would have raised any required funds via any number of sources, but that’s not really the point.

The point is that the reserve requirement can only impose a “cost” penalty on the bank, not constrain it from lending. Further, in the aggregate, central banks act to avoid such additional costs which would cause the interbank rate to trade above the central bank’s target rate by ACCOMMODATING the banking system’s demands for balances to meet reserve requirements before such overdrafts occur. They do this out of necessity since leaving banks in the aggregate short of meeting requirements would mean that deficient banks would bid the interbank rate up as they tried to entice other banks to lend, pushing the rate up above the central bank’s target until it reached the central bank’s stated penalty for a reserve deficiency. At this point, banks would be theoretically indifferent between borrowing from another bank and simply incurring the overdraft at the same rate.

Now consider a bank with substantial ERs. Does it have any more operational ability to create a loan than the bank in the previous example? Certainly not, as the bank in the previous example has NO operational limits to its abilities to lend–it will obtain any necessary reserves from other banks and the central bank will provide more to the aggregate system should that be necessary to achieve its target rate.

The only instance in which the previous bank might change its plans is where a central bank does not accommodate its interest rate target but instead provides the overdraft at a penalty to a deficient bank. But all this would do is raise the interest rate the bank would be willing to lend at (since its own costs would have risen via the penalty). So, again, the bank would not be constrained by reserve availability. It just means that infinite funds would still be available but at a higher interest rate. Again, this has not been the practice of modern central banks (even for the Fed during its so-called “monetarist experiment”).

As an aside, let’s state this another way. That is, a central bank that attempts to target the quantity of aggregate reserve balances such that it forces individual banks to meet reserve requirements via overdrafts at a penalty is NOT targeting directly the quantity of reserve balances but rather setting a de facto target at its stated penalty rate. As Warren Mosler says, central bank operations are ALWAYS about price, not quantity, as a matter of institutional structure.

Now assume that the excess reserve tax is imposed on the bank holding the ERs. Does this make it more likely to lend? Given that the ERs don’t give it any more ability to create a loan in the first place, unless the tax somehow gets the bank to lower its lending standards (not necessarily the best idea given the current status of banks), the answer is clearly NO.

What the tax DOES do is encourage the bank to get rid of its ERs by lending in the interbank market. But because only changes to the Fed’s balance sheet can alter the aggregate quantity of reserve balances (as I said, reserve accounting would be shown to be important yet again), lending in the interbank market can only shift existing balances from bank to bank. If the aggregate banking system is left holding undesired excess balances that the Fed does not drain, the fed funds rate is bid down, at the limit to the rate paid to banks for holding ERs, which because of the excess reserve tax has been set below zero.

Again, the fact that the fed funds rate has fallen isn’t the point. The point is that the money multiplier, or “excess cash balance” mechanism is NOT applicable to our monetary system.

In my previous post, I pointed out that another of this tax’s effects would be to reduce bank profits for those left holding the ERs. Sumner’s counter was this: “Another mistake is to assume it would hurt bank profits. It could, but need not if the Fed doesn’t want it to. They could simply pay positive interest on RRs to offset the negative interest on ERs. All this is explained in this post”

In his original post, he gives as an initial example an excess reserve tax of 4% and payment on required reserves of 4%.

But again, the bank with no ERs has the same ability to create a loan as the bank with ERs. So, to stimulate lending, the only thing the ER tax can possibly do is encourage banks left holding the undesired ERs (assuming they aren’t drained by the Fed) to lower lending standards below those of banks without ERs in the hope that more would-be borrowers come though their doors.

All the evidence from volumes of empirical research on bank reserve behavior is very clear—banks don’t make an “asset allocation” decision between ERs at below market rates (lots of experience in the real world with these, as it’s been the normal state of affairs) and lending to willing, creditworthy borrowers. The two are unrelated as explained above (or at least mostly explained . . . one could be a great deal more technical about payment settlement-related motives for holding ERs and how this is also unrelated to lending), though the excess reserve tax tries to make them related by forcing banks in the aggregate to hold undesired balances, imposing a tax if they don’t create loans/deposits, and then paying them to make more loans/deposits.

So, again, the banks left holding the ERs would see their profits fall.

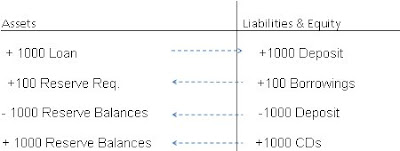

Banks could in fact avoid the excess reserve tax and receive the interest payment on required reserves by making NO loans at all if they instead found ways to incentivize, entice, or even force customers currently holding non-reserveable liabilities (savings, CDs, money market accounts) to shift these to reserveable liabilities (deposits). In fact, rather than lending, this sort of reclassification of existing balances is probably the outcome of the excess reserve tax plus payment for required reserves.

For instance, banks would probably cease all operations related to moving customer deposits into retail sweep accounts previously intended to avoid reserve requirements. This alone would reclassify about $600 billion or so in money market accounts as deposits and create somewhere around $50 billion in reserve requirements. As banks continued to “encourage” deposit accounts over non-reserveable accounts to reflect their own incentive to convert excess balances to required balances, still more balances could be reclassified.

So again, like the currency tax, we just get a reclassification of existing balances . . . this time toward deposits rather than away from them as the currency tax would do. Also like the currency tax, then, we don’t get any more spending and we therefore don’t get more aggregate demand. In other words, just as my spending plans didn’t change as I moved away from deposits to avoid Buiter’s proposed tax on transaction balances in the previous post, my spending plans also don’t change as I move toward transaction balances to avoid banks’ newly imposed disincentives for holding savings-type of accounts resulting from the mix of excess reserve tax/reserve requirement incentive they are facing.

A better way to increase aggregate demand than going to all these disruptive extremes that can only work if they reduce lending standards or reduce savings desires would be to raise household incomes and business profits directly and thereby increase both consumption and the likelihood loans can be paid back. I suggested a payroll tax holiday as one way to do this . . .this and other complementary proposals have been repeatedly discussed by L. Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton, and Pavlina Tcherneva on this blog (and Warren Mosler and Mike Norman have done the same on theirs).

In closing, I ended the previous post by writing “unfortunately, those recommending penalties on currency, deposits, or reserves don’t fully understand monetary operations given that their basic framework is inapplicable to a modern monetary system such as ours.” Given that my conclusions here—that the excess reserve tax is based upon a lack of understanding of monetary operations (and reserve accounting in particular) and the inapplicable money multiplier—are much the same, there is no reason to alter that initial assessment.