By Stephanie Kelton

Brad DeLong, Mark Thoma and David Beckworth have spent the last few days debating the extent to which Alan Greenspan’s easy money stance (2001-2004) qualifies as a “significant policy mistake.” DeLong asks:

“Should Alan Greenspan have kept interest rates higher and triggered a much bigger recession with much higher unemployment back then in order to head off the growth of a housing bubble?”

As I see it, these are really two separate questions: (1) Did Greenspan’s easy money policy cause the bubble? (2) Should Greenspan have attempted to diffuse the bubble – with higher interest rates — once he identified it?

I wrestled with these precise questions in a presentation I have given many times since last fall. I started with Greenspan’s own argument.

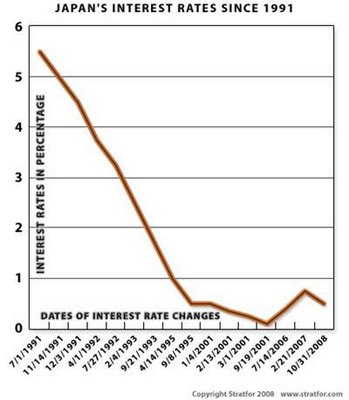

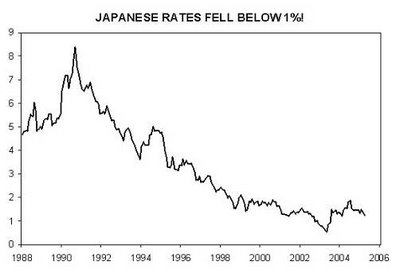

In an interview with a reporter from the Wall Street Journal, Greenspan characterized himself as “an old 19th-century liberal who is uncomfortable with low interest rates.” Yet he lowered the federal funds rate thirteen times from 2001-2003, pushing it to just 1% at the end of the easing cycle. Looking back on that period, Greenspan admits that his “inner soul didn’t feel comfortable” with those sustained rate cuts, but he maintains that it was the right policy in the aftermath of the dot.com bubble. Moreover, he insists that the run-up in housing prices was not the result of his monetary easing and that “no sensible policy . . . could have prevented the housing bubble.” Indeed, Greenspan maintains that the housing bubble emerged because risk premiums – not interest rates – were kept too low for too long.

As Greenspan argued in his memoir, geopolitical forces outside the control of the Fed caused risk premiums to decline, and this, ultimately, led to the housing bubble. In his view, there was nothing the Fed could have done to prevent the decline in risk premiums, which had its roots “in the aftermath of the Cold War.” His argument runs as follows: Over the past quarter century, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union, China’s protection of foreigner’s property rights, the adoption of export-led growth models by the Asian Tigers, and the reinstatement of free trade produced significant productivity growth in much of the developing world. And because developing nations save more than developed nations – in part due to weaker social safety nets – there has been a shift in the share of world GDP from low-saving developed nations to higher-saving developing countries. Greenspan believes that this resulted in excessive savings worldwide (as saving growth greatly exceeded planned investment) and placed significant downward pressure on global interest rates. Thus, as he sees it, the demise of central planning ushered in an era of competitive pressures that reduced labor compensation and lowered inflation expectations. As a result, the global economy experienced years of unprecedented growth, markets became euphoric, and risk became underpriced.

This takes me back to Mark Thoma’s argument. Thoma believes that Greenspan’s easy money policy was a significant policy mistake. He said:

“It seems, then, the Fed did push its policy rate below the natural rate and in the process created a huge Wicksellian-type disequilibria.”

But Greenspan seems to be arguing that the natural rate was also declining, so it isn’t clear that market rates were pushed too low. And while I don’t buy Greenspan’s argument, I also don’t believe easy money sunk the economy.

I think there is an alternative explanation that is based on factors that had little (if anything) to do with Greenspan’s monetary easing from 2001-2003 or with geopolitical factors. To be sure, this sustained period of low interest rates made home ownership more affordable and increased the demand for home loans. But the increase in home prices could not have expanded at such a frenzied pace in the absence of rating agencies, mortgage insurance companies and appraisers who validated the process at each step.

As my colleague Jan Kregel put it, “the current crisis has little to do with the mortgage market (or subprime mortgages per se), but rather with the basic structure of a financial system that overestimates creditworthiness and underprices risk.” Like Greenspan, Kregel views the housing bubble and ensuing credit crisis as the inevitable consequence of sustaining risk premiums at too low a level. Unlike Greenspan, however, he maintains that bubbles and crises are an inherent feature of the “originate and distribute” model. Under the current model, risks become discounted because “those who bear the risk are no longer responsible for evaluating the creditworthiness of borrowers.”

Thus, with respect to the debate over the role of low interest rates, I would argue that it was not loose monetary policy but loose lending standards (abetted by a hefty dose of control fraud) that brought us to where we are today.

Now to the second question: Should Greenspan have raised rates sooner, in order to “head off the bubble”?

DeLong has admitted to being “genuinely not sure which side I come down on in this debate.” Unlike Thoma, DeLong appears sympathetic, even empathetic, trying to imagine what it must have been like to be in Alan Greenspan’s shoes:

“If we push interest rates up, Alan Greenspan thought, millions of extra Americans will be unemployed and without incomes to no benefit . . . . If we allow interest rates to fall, Alan Greenspan thought, these extra workers will be employed building houses and making things to sell to all the people whose incomes come from the construction sector . . . . If a bubble does develop, Greenspan thought, then will be the time to deal with that.”

But Alan Greenspan was never so clear-headed in his thinking. Indeed, like DeLong, Greenspan appears to have been genuinely conflicted. He has argued that it is virtually impossible to spot an emerging bubble:

“The stock market as best I can judge is high; it’s not that there is a bubble in there; I am not sure we would know a bubble if we saw it, at least in advance.” (FOMC transcripts, May 1996)

Then, just four months later, Greenspan indicated that he could not only spot an emerging bubble but that it would be dangerous to ignore it:

“Everyone enjoys an economic party, but the long term costs of a bubble to the economy and society are potentially great. As in the U.S. in the late 1920s and Japan in the late 1980s, the case for a central bank to ultimately to burst that bubble becomes overwhelming. I think that it is far better that we do so while the bubble still resembles surface froth, and before the bubble caries to the economy to stratospheric heights. Whenever we do it, it is going to be painful, however.” (FOMC transcripts, September 1996)

In 2004, Greenspan spoke before the American Economics Association and took the position that it is dangerous to address a bubble, insisting that it is preferable to let the bubble burst on its own and then lower interest rates to help the economy recover:

“Instead of trying to contain a putative bubble by drastic actions with largely unpredictable consequences, we chose, as noted in our mid-1999 congressional testimony, to focus on policies to mitigate the fallout when it occurs and, hopefully, ease the transition to the next expansion”.

Since then, Greenspan has argued that the Fed actually was trying to address the emerging housing bubble when it began to raise rates in the mid-2000s, but he says the policy was unsuccessful because long-term rates remained stubbornly low. Of course, he also said:

“I don’t remember a case when the process by which the decision making at the Federal Reserve failed.”

And I think we can all agree to disagree on that point.