Arthur Laffer has taken aim at Chairman Bernanke and President Obama, warning that somewhere down the road their policies will exact a huge price on the American economy. With respect to the Chairman’s handling of monetary policy, Mr. Laffer predicts “rapidly rising prices and much, much higher interest rates.” I am not going to critique Laffer on this point, because Paul Krugman and Mark Thoma have already done so in fine form.

Instead, I want to address Mr. Laffer’s fiscal concerns. He said:

“Here we stand more than a year into a grave economic crisis with a projected budget deficit of 13% of GDP. . . With U.S. GDP and federal tax receipts at about $14 trillion and $2.4 trillion respectively, such a debt all but guarantees higher interest rates, massive tax increases, and partial default on government promises.”

I believe that he is wrong on each of the above points, and here is why:

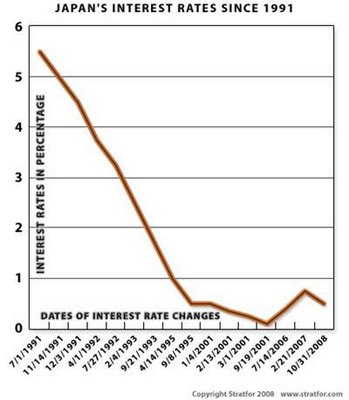

1. Increases in the federal deficit tend to decrease, rather than increase, interest rates. This is because deficit spending leads to a net injection of reserves into the banking system. (And big deficits imply big injections of reserves.) When the banking system is flush with reserves, the price of those reserves – in the U.S. the federal funds rate – is driven to zero (yes, zero!). Unless a zero-bid is consistent with Fed policy, the central bank will begin selling bonds in order to drain excess reserves. The bond sales continue until the fed funds rate falls within the Fed’s target band. The Federal Reserve sets the key interest rate in the U.S., and it can always hit any nominal interest rate it chooses, regardless of the size of the budget deficit (or debt). And this isn’t just true of the Fed. Just look at the Japanese experience:

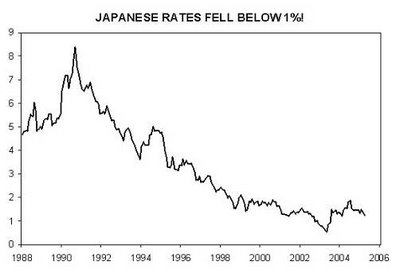

Thus, despite a debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 200%, the Bank of Japan never lost the ability to set the key overnight interest rate, which has remained below 1% for about a decade. And, the debt didn’t drive long-term rates higher either. The chart below shows that rates on 10-yr government bonds trended sharply downward as Japan’s public sector debt exploded:

Laffer’s prediction about what will happen to U.S. interest rates as a consequence of the Obama stimulus package are based on a faulty understanding of the relationship between deficit spending, bank reserves and interest rates. The Japanese experience serves as prime example of his flawed logic. (My fellow bloggers, Scott Fullwiler, Randy Wray and I have all published numerous articles that lay out the technical details surrounding the coordination of Treasury Fed operations and the management of U.S. interest rates.)

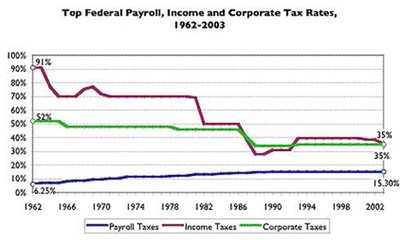

2. Increases in the federal deficit (and the subsequent run-up in outstanding debt) do not mandate higher taxes in the future. Taxes do not “pay for” the deficits we ran in the past. Taxes drain reserves (an important function) and constrain aggregate demand. Tax revenue obviously moves endogenously, with the business cycle, but revenues can also change as a matter of policy. What Mr. Laffer is apparently arguing is that today’s deficits will require “tomorrow’s” leaders to raise marginal tax rates (or impose new taxes). But this isn’t the U.S. experience.

Corporate taxes, as well as taxes on the wealthiest Americans, have trended downward for decades, even as the U.S. debt quadrupled in size.

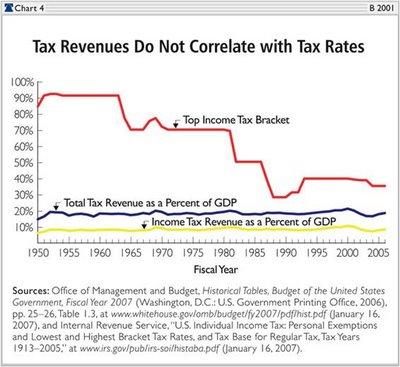

And, while payroll taxes have risen steadily over the past 40 years, tax revenues, as a percentage of GDP have hardly budged in more than 50 years.

Thus, Laffer’s assertion that the current run-up in government debt will require “massive tax increases” isn’t borne out by our experience. And, it wasn’t the case in Japan either:

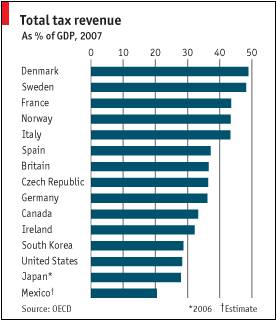

Despite an explosive increase in the government debt in both the U.S. (throughout the 1980s and again under George W. Bush) and Japan (especially in the late 1990s and early 2000s), taxes in both countries are among the lowest in the developed world.

3. Laffer contends that a “partial default on government promises” is an inevitable consequence of the Obama administration’s “ill-conceived” fiscal policies. A statement like this is at best misleading and at worst intellectually dishonest.

As any serious macro economist knows, a government like the United States – i.e. one that controls its own currency – can meet any and all outstanding financial obligations, provided the debts are denominated in the national currency. This is a point that Alan Greenspan made several years ago, when he wrote that “the U.S. government, by virtue of its ability to create money, can never become insolvent with respect to obligations in its own currency.”

12 responses to “Will the Run-Up in Government Debt Doom Us All?”