The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has just released its long-term budget outlook. The dismal report warns:

As Kelton and Wray have explained in earlier posts, the federal government spends by crediting bank accounts. Period. Tax payments to the government result in the destruction of money — high-powered money to be exact — as the banking system clears the checks and reserve accounts are debited. In other words, taxes don’t provide the government with “money to spend”. Tax payments destroy money. Not in theory. Not by assumption. By definition.

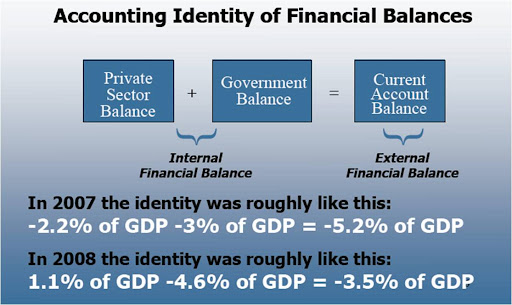

Second, growing budget deficits do not reduce national savings. They do just the opposite. Indeed, the private sector — households and firms taken as a whole — cannot attain a surplus position unless some other sector (the public sector or the foreign sector) takes the opposite position. Again, it is an indisputable feature of balance sheet accounting that is governed by the following identity:

Private Sector Surplus = Public Sector Deficit + Current Account Surplus

This fundamental accounting identity can be found in any decent International Economics texbook (see, e.g., Krugman and Obstfeld), and it is one of the most important macroeconomic concepts we can think of. It demonstrates the conditions under which national savings will be positive. Not in theory. Not by assumption. By definition.

Source: Levy Institute

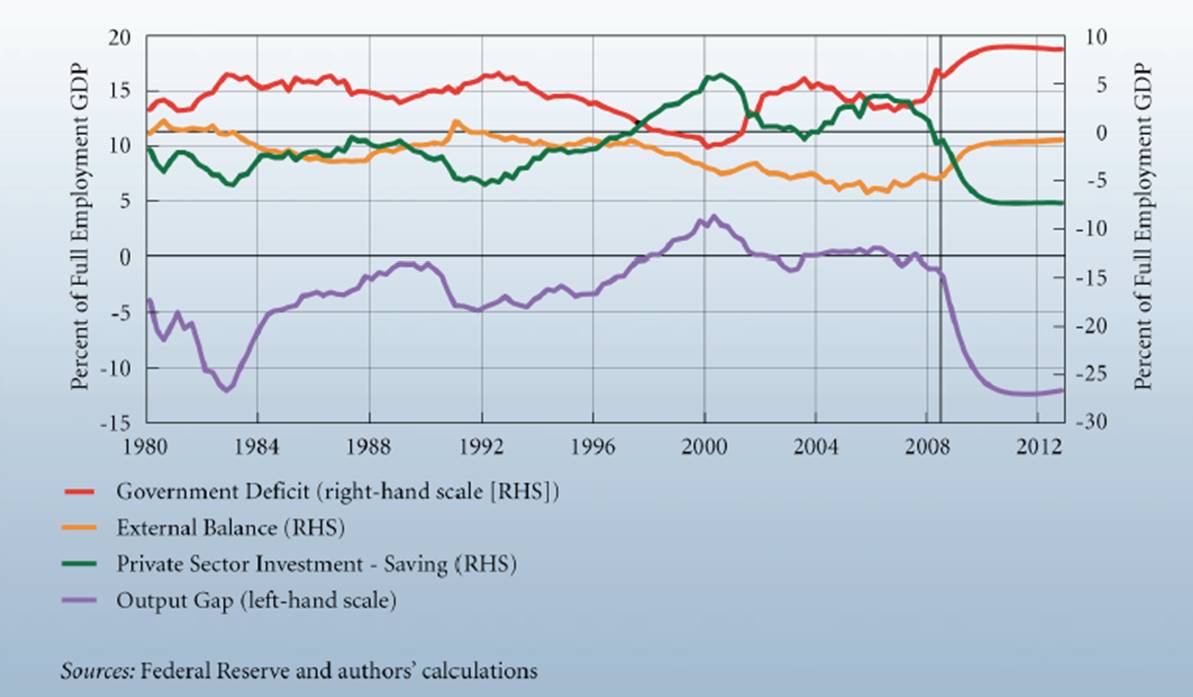

To appreciate the interplay, consider the main sector balances in 2004. The public sector’s deficit of about 5% of GDP was just enough to offset the 5% current account deficit, leaving the private sector with no addition to its net saving (i.e. private sector savings were zero). Today, in contrast, private savings are up sharply because: (1) the public deficit is up sharply and (2) the external deficit is declining. Add today’s (rising) public deficit to today’s (falling) current account deficit and, voila, the CBO’s much-feared explosion in the government deficit has translated into an explosion in private savings.