by Warren Mosler and Eileen Debold

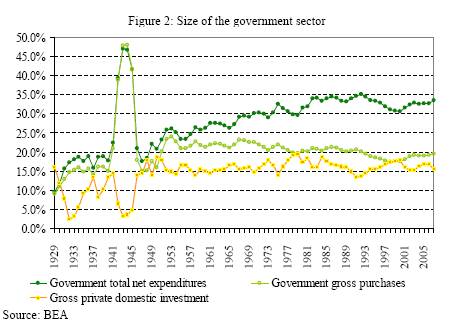

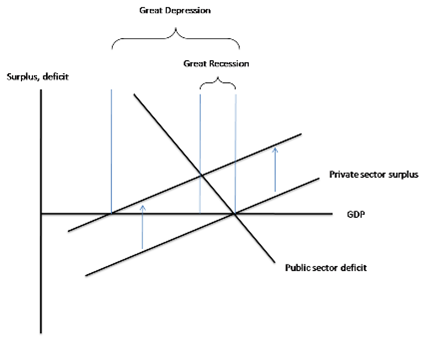

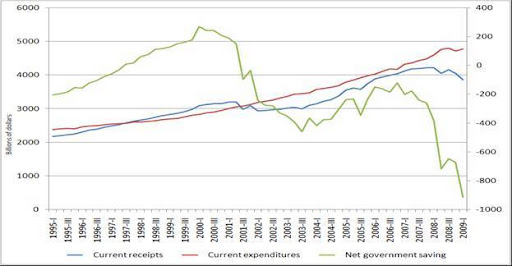

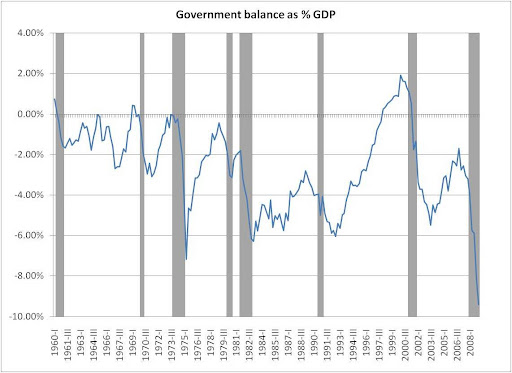

Just as the Corps of Engineers sustains the army’s fighting ability, our financial engineers have been sustaining the US post-Cold War economic expansion. Financial engineering has effectively supported an expansion that could have long ago succumbed to the ‘financial gravity’ economists call ‘fiscal drag.’ For even with lower US tax rates, the surge in economic growth has generated federal tax revenues in excess of federal spending. This has led to both record high budget surpluses and the record low consumer savings that is, for all practical purposes, the other side of the same coin. As the accounting identity states, a government surplus is necessarily equal to the non-government deficit. The domestic consumer is the largest component of ‘non-government’ trailed by domestic corporations, and non- resident (foreign) corporations, governments, and individuals.

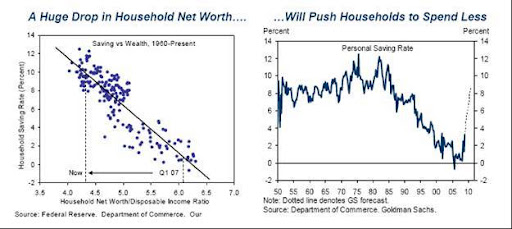

It is our financial engineers who have empowered American consumers with innovative forms of credit, enabling them to sustain spending far in excess of income even as their net nominal wealth (savings) declines. Financial engineering has also empowered private-sector firms to increase their debt as they finance the increased investment and production. And, with technology increasing productivity as unemployment has fallen, prices have remained acceptably stable.

Financial engineering begins deep inside the major commercial and investment banks with ‘credit scoring.’ This is typically a sophisticated analytical process whereby a loan application is thoroughly analyzed and assigned a number representing its credit quality. The process has a high degree of precision, as evidenced by low delinquencies and defaults even as credit has expanded at a torrid pace. Asset securitization, the realm of another highly specialized corps of financial engineers, then allows non-traditional investors to be part of the demand for this lending-based product. Loans are pooled together, with the resulting cash flows sliced and diced to meet the specific needs of a multitude of different investors. Additionally, the financial engineers structure securities with a careful eye to the credit criteria of the major credit rating services most investors have come to rely on. The resulting structures range from lower yielding unleveraged AAA rated senior securities to high yielding, high risk, ‘leveraged leverage’ mezzanine securities of pools of mezzanine securities.

Private sector debt growth can only exceed income growth for a limited time, even if the debt growth is also driving asset prices higher. At some point the supply of credit wanes. But not for lack of available funds (since loans create deposits), but when even our elite cadre of financial engineers exhaust the supply of creditworthy borrowers who are willing to spend. When that happens asset prices go sideways, consumer spending and retail sales soften, jobless claims trend higher, leading indicators turn south, and car sales and housing slump. There is a scramble to sell assets and not spend income in a futile attempt to replace the nominal wealth being drained by the surplus. Consequently, as unemployment bottoms and begins to increase, personal and corporate income decelerate, and government revenues soon fall short of expenditures as the economy slips into recession. The financial engineers then shift their focus to the repackaging of defaulted receivables.

Both Presidential candidates have voiced their support for maintaining the surplus to pay down the debt, overlooking the iron link between declining savings and budget surpluses. For as long as the government continues to tax more than it spends, nominal $US savings (the combined holdings of residents and non-residents) will be drained, keeping us dependent on financial engineering to sustain spending and growth in the global economy.

Mr. Mosler is the chairman of A.V.M. L.P. and director of economic analysis, III Advisors Ltd. Ms. Debold is vice president, Global Risk Management Services, The Bank of New York.

***************

Another interesting piece, an interview of Professor L. Randall Wray, almost 9 years old saw the current crisis coming.

Q:Based on the current economic scenario, and taking into account the recent interest rates increases, how probable is the hypothesis of a “soft-landing” for the American economy?

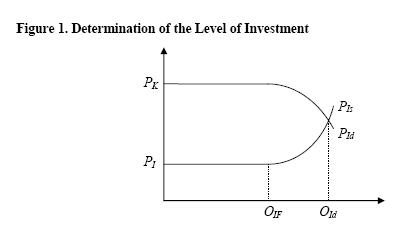

LRW: It is highly improbable that an economic slowdown could stop at a “soft-landing”, given economic conditions that exist today. The U.S. expansion of the past half dozen years has been driven to an unprecedented extent by private sector borrowing. Indeed, the private sector has been spending more than its income in recent years, with its deficit reaching 5.5% of GDP in 1999. In order for the economy to continue to grow, this gap between income and spending must continue to grow. My colleague at the Jerome Levy Economics Institute, Wynne Godley, has projected that the private sector’s deficit would have to climb to well over 8% of GDP by 2005 in order to keep economic growth just above 2.5%. Even that is below the current rate of growth (about 4%). A smaller private sector deficit would mean even lower growth. There are two problems with this scenario. First, our private sector has never run deficits in the past as large as those experienced in this current expansion. In the past, private sector deficits reached a maximum of about 1% of GDP and then quickly reversed toward surplus as households and firms cut back spending to bring it below income. Not only are current deficits already five times higher than anything achieved in the past, they have already lasted two or three times longer than any previous deficits. Even more importantly, the private sector has had to borrow in order to finance its deficit spending, which increases its indebtedness. Private sector debt is already at a record level relative to disposable income. As interest rates rise, this increases what are known as debt service burdens—the percent of disposable income that must go to pay interest (and to repay principal) on debt. In combination with an economic slowdown, which reduces the growth of disposable income, many firms and households will find it impossible to meet their payment commitments. Defaults and bankruptcies are already on the rise, and things will only get worse. Thus, I believe there is a real danger that an economic slowdown could degenerate into a deep recession—or even worse.

***************

Wray also saw it coming (see here), as he put it:

How would Minsky explain the processes that brought us to this point, and what would he think about the prospects for continued Goldilocks growth?

First, I think he would argue that consumers became ready, willing, and able to borrow, probably to a relative degree not seen since the 1920s. Credit cards became much more available; lenders expanded credit to sub-prime borrowers; bad publicity about redlining provided the stick, and the Community Reinvestment Act provided the carrot to expand the supply of loans to lower income homeowners; deregulation of financial institutions enhanced competition. All of these things made it easier for consumers to borrow. Consumers were also more willing to borrow. As Minsky used to say, as memories of the Great Depression fade, people become more willing to commit future income flows to debt service. The last general debt deflation is beyond the experience of almost the whole population. Even the last recession was almost half a generation ago. And it isn’t hard to convince oneself that since we’ve really only had one recession in nearly a generation, downside risks are small. Add on top of that the stock market’s irrational exuberance and the wealth effect, and you can pretty easily explain consumer willingness to borrow.

I would add one more point, which is that until very recently, most Americans had not regained their real 1973 incomes. Even over the course of the Clinton expansion, real wage growth has been very low. Americans are not used to living through a quarter of a century without rising living standards. Of course, the first reaction was to increase the number of earners per family—but even that has allowed only a small increase of real income. Thus, I think it isn’t surprising that consumers ran out and borrowed as soon as they became reasonably confident that the expansion would last.

The result has been consistently high growth of consumer credit…The expansion might not stall out in the coming months, but continued expansion in the face of a trade deficit and budget surplus requires that the private sector’s deficit and thus debt load continue to rise without limit…What would Minsky recommend? So long as private sector spending continues at a robust pace, he would probably recommend that we do nothing today about the budget surplus. He would oppose any policies that would tie the hands of fiscal policy to maintenance of a surplus. Rather, he would push toward recognition that tax cuts and spending increases will be needed as soon as private sector spending falters. That means it is time to begin discussion of the types of tax cuts and spending programs that will be rushed through as the recession begins. For the longer run, he would recommend relaxation of the fiscal stance so that surpluses would be achieved only at high growth rates (in excess of the full employment rate of economic growth). For the shorter run, he would oppose monetary tightening, which would increase debt service ratios and push financial structures into speculative or Ponzi positions. He would support policies aimed at reducing “irrational exuberance” of financial markets; most importantly, increased margin requirements on stock markets would be far more effective and narrowly targeted than are general interest rate hikes that have been the sole instrument of Fed policy to this point. Most importantly, Minsky would try to shift the focus of policy formation away from the belief that monetary policy, alone, can be used to “fine-tune” the economy, and from the belief that fiscal policy should be geared toward running perpetual surpluses—in Minsky’s view, this would be high risk strategy without strong theoretical foundations.