SECRET EMAILS SHOW GEITHNER’S NYFED FORCED AIG TO HIDE DATA

By L. Randall Wray

SECRET EMAILS SHOW GEITHNER’S NYFED FORCED AIG TO HIDE DATA

By L. Randall Wray

Posted in L. Randall Wray, Policy and Reform, Regulation, Uncategorized

Tagged Federal Reserve, L. Randall Wray, Policy and Reform, regulation

BERNANKE’S APOLOGY FALLS FLAT

By L. Randall Wray

There appear to be at least three reasons for Bernanke’s admission that the Fed did not do its job. First, and most obviously, Bernanke is up for reappointment (his term expires January 31)—and he will not sail through. The public is mad as hell, and politicians will have to put him through the wringer or face voter’s wrath in the next election. So Bernanke will have to appear contrite, and will apologize for his misdeeds many more times while Congress makes him sweat it out.

Second, Congress is actually considering whether it should strip the Fed of all regulatory and supervisory authority, given its miserable performance over the past decade—during which the Fed has consistently demonstrated that it has neither the competence nor the will to restrain Wall Street’s bankers. Since Greenspan took over the helm, the Fed has never seen a financial instrument or practice that it did not like—no matter how predatory or dangerous it was. Adjustable rate mortgages with teaser rates that would reset to levels guaranteed to produce defaults? Greenspan praised them (see here). Liar loans? Bring them on! NINJA loans (no income, no job, no assets)? No problem! Credit default swaps that let one gamble on the death of assets, firms, and countries? Prohibit government from regulating them! So Bernanke has to grovel and beg Congress to let the Fed retain at least some of its authority.

Third, many commentators blame the Fed for the crisis, arguing that it kept interest rates too low for too long, fueling the real estate bubble. Bernanke argues “When historical relationships are taken into account, it is difficult to ascribe the house price bubble either to monetary policy or to the broader macroeconomic environment”. If he can convince Congress that the problem was lack of oversight and regulation he can shift at least some of the blame to Treasury and Congress—since it was Treasury Secretary Rubin, and his protégé Summers, as well as Barney Frank, Christopher Dodd, and many others (significantly, Democrats who will now decide the Fed’s fate) who pushed through the deregulation bills in 1999 and 2000. He figures that if the Fed now supports re-regulation, he will be forgiven and the Democrats will be too embarrassed to admit their own misdeeds. (Significantly, Dodd has announced his retirement, in recognition of the role he played in creating the crisis. Another mea culpa on the way?)

While I do believe the Fed should be stripped of all such authority, I am sympathetic to his argument about monetary policy. Low interest rates do not cause bubbles. The Fed kept interest rates low after the NASDAQ crash because it feared deflation in the face of significant downward pressures on wages and prices globally (see here). The belief was that low interest rates would keep borrowing costs low for firms and households, helping to promote spending and recovery. In truth, spending is not very interest sensitive and the economy stumbled along in a “jobless recovery” in spite of the low rates. What was actually needed was a fiscal stimulus (if anything, low rates are counterproductive because they reduce government interest spending on its debt—as Japan’s experience taught us over the past couple of decades—but that is a point for another blog).

Still, the Fed was following conventional wisdom, and only began to gradually raise rates when job growth picked up in 2004. Over the following years, the Fed kept raising rates, and economic growth improved. (So much for conventional wisdom!) The worst excesses in real estate markets began only after the Fed had started raising rates, and lending standards continued their downward spiral the higher the Fed pushed its target interest rate. In other words, contrary to what many are arguing, the Fed DID raise rates but this had no impact in real estate markets.

Why not? Two main reasons. First, recall that Greenspan had promoted adjustable rate mortgages with teasers. No matter how high the Fed pushed rates, lenders could offer “option rate” deals in which borrowers would pay a rate of 1 or 2 percent for two to three years, after which there would be a huge reset. Lenders ensured the borrowers that there was no reason to worry about resets, since they would refinance into another option rate mortgage before the reset. That is the beauty of ARMs—they virtually eliminate the impact of monetary policy on real estate.

Second, and this was the key, house prices would only go up. At the time of refinance, the borrower would have far more equity in the home, thus obtain a better mortgage. Further, the borrower could flip the house and walk away with cash. While I will not go into this now, public policy actually encouraged homeowners to look at their houses as assets, rather than as homes (see here) (And now that many are walking away from underwater mortgages—treating houses as assets that became bad deals—policy makers and banksters are shocked, shocked!, that borrowers are treating their homes as nothing but bad assets.)

In truth, when speculation comes to dominate an asset class, there is no interest rate hike that can kill a bubble. If one expects asset prices to rise by 20%, 30%, or more per year, an interest rate of 10% will not dampen enthusiasm. To kill the housing boom, the Fed would have had to engage in a Volcker-like double-digit rate hike (in the early 1980s, he raised short-term interest rates above 20%). There was no political will in Washington (either at the Fed or the White House) for such drastic measures. Nor was there any reason to do this. Bernanke is quite correct: the Fed could have and should have killed the real estate boom with much less pain by directly clamping down on lenders, prohibiting the dangerous practices that were rampant.

Is there any reason to believe that Bernanke is the right Chairman, or that the Fed is the right institution, to lead the effort to re-regulate and re-supervise the financial sector? Quite simply, no.

The Bernanke-led Fed still does not understand monetary operations, as indicated by its recently announced plan to unwind its balance sheet. Over the course of the crisis, the Fed invented new procedures such as auctions through which it provided reserves. Throughout, it always was focused on quantities, rather than prices, using quantitative constraints on the size of the auctions. Further, Bernanke continually promoted “quantitative easing”, reflecting the view that quantities are what matter. Now, the Fed has begun to worry about the size of its balance sheet—and also the size of reserve holdings of the banking system (the other side of the balance sheet coin, because the Fed buys assets by issuing reserves). Still following the thoroughly discredited theory of Milton Friedman, too many bank reserves are supposed to promote too much lending which then causes too much spending and hence inflation. Thus, Bernanke and many outside the Fed fret about how the Fed can reduce outstanding reserves to prevent incipient inflation. The Fed proposes to create new bonds it will sell to reverse the “quantitative easing”.

Actually, the Fed’s tool is price, not quantity, of reserves. When the crisis hit, the Fed should have opened its discount window to lend reserves without limit, to all comers, and without collateral. That is how you stop a run. The Fed’s dallying and dillying about worsened the liquidity crisis, but it eventually provided the reserves that the financial institutions wanted to hold and its balance sheet eventually grew to $2 trillion. Banks are still worried about counterparty risk and possible runs, so they remain willing to hold massive amounts of reserves. When they decide risks have declined, they will begin to reduce reserve holdings. This will not require any special practices by the Fed. Banks will repay their loans from the Fed, using reserves. This automatically reduces reserves and the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. They will offer undesired reserves in the overnight, fed funds market. Since many banks will be trying to unload reserves at the same time, this will put downward pressure on the fed funds rate. The Fed will then offer to sell assets it is holding to mop up the excess reserves (banks will use reserves to buy assets the Fed offers). This will also reduce reserves and the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. All of this will happen automatically, following the same procedures the Fed has always followed. All it needs to do is to watch the fed funds rate, and when it falls below target the Fed will drain reserves to relieve the downward pressure on overnight rates.

Quantitative easing was a misguided notion, and reversal of quantitative easing is similarly misguided. It simply indicates that Bernanke still does not understand how the Fed operates. In truth, formulating and implementing monetary policy is extremely simple and can be reduced to the following:

1. Offer to lend reserves at the discount window at 50 basis points to all qualifying institutions;

2. Pay 25 basis points on reserve holdings;

3. Perform par clearing of checks between banks, and for the Treasury.

Surely President Obama can find a chair who can do that.

The Fed’s relationship with banks is too cozy to make it a good regulator. It is, after all, owned by private banks. The Fed’s district banks are often run by bankers, and district Fed presidents take turns sitting on the policy-making FOMC. There is a particularly incestuous relationship between the NYFed and Wall Street banks—with Timmy Geithner as a prime example of the dangers posed (“I’ve never been a regulator” proclaimed the former head of the NYFed). It does not have the proper culture to closely supervise financial institutions. Its top body, the Board of Governors, are political appointees often with no experience in regulation (many are academic economists, typically mainstream and with a free market orientation). While the FDIC was also mostly asleep at the wheel over the past decade, it does have the proper culture and experience to take over responsibility for regulating and supervising the financial sector. With some management changes, and hiring of a team of criminologists tasked to pursue fraud, the FDIC is the right institution for this job.

An interesting article by Ryan Grym on Fed control of research. “Priceless: How The Federal Reserve Bought The Economics Profession“

According to the article,

The Federal Reserve, through its extensive network of consultants, visiting scholars, alumni and staff economists, so thoroughly dominates the field of economics that real criticism of the central bank has become a career liability for members of the profession, an investigation by the Huffington Post has found.

This dominance helps explain how, even after the Fed failed to foresee the greatest economic collapse since the Great Depression, the central bank has largely escaped criticism from academic economists. In the Fed’s thrall, the economists missed it, too.

“The Fed has a lock on the economics world,” says Joshua Rosner, a Wall Street analyst who correctly called the meltdown. “There is no room for other views, which I guess is why economists got it so wrong.”

One critical way the Fed exerts control on academic economists is through its relationships with the field’s gatekeepers. For instance, at the Journal of Monetary Economics, a must-publish venue for rising economists, more than half of the editorial board members are currently on the Fed payroll — and the rest have been in the past.

Even the late Milton Friedman, whose monetary economic theories heavily influenced Greenspan, was concerned about the stifled nature of the debate.

Friedman, in a 1993 letter to Auerbach that the author quotes in his book, argued that the Fed practice was harming objectivity: “I cannot disagree with you that having something like 500 economists is extremely unhealthy. As you say, it is not conducive to independent, objective research. You and I know there has been censorship of the material published. Equally important, the location of the economists in the Federal Reserve has had a significant influence on the kind of research they do, biasing that research toward noncontroversial technical papers on method as opposed to substantive papers on policy and results,” Friedman wrote.

It is time for a new start.

Don’t get me wrong. I want retribution, too. We need a “bank holiday”, to begin next Friday: close suspect banks including all of the biggest that were subjected to the wimpy “stress test”. Spend the weekend going through the books and then on Monday begin to resolve the insolvent, to prosecute the banksters for fraud, and to retrieve from them their outsized bonuses financed by the public purse. It is payback time. My only objection is to the notion that we should be celebrating because the Fed appears to have made a profit on (a small part of) the bailout.

Second, there is every reason to suspect that the banks that have repaid TARP money and those making payments on loans from the Fed are still massively insolvent at any true valuation of the toxic waste still on their balance sheets. Recent reported profit in the financial sector is window-dressing, designed to fuel the irrationally exuberant stock market bubble. This will allow traders and other employees to cash in their stock options to recover some of the losses they incurred last year, even as bonuses are boosted for this year. Indeed, the main reason for returning the borrowed funds is to escape controls on executive salaries and bonuses. And, finally, it provides some important PR to counteract the growing anger over the financial bailouts. Only the foolish or those with some dog in the hunt will believe that the banksters have really managed to restore health to the financial sector as they continue to do what they did to cause the crisis.

Last but not least, the Fed’s “profits” are based on an infinitesimally small fraction of its ramped-up operations—its liquidity facilities (that also include discount window loans and currency swaps with other central banks, purchases of commercial paper and financing for investors in asset-backed securities). It has also spent $1.75 trillion buying bad assets, with any losses on those excluded from the profits numbers. The government’s profits also exclude current and expected spending on the rest of its reported $23.7 trillion dollar commitment to the financial bailout and fiscal stimulus package. The failure of just one medium-sized bank could easily wipe out the entire $14 billion of profits that has attracted so much notice. (See also Dean Baker on the government’s “profits”)

It is ironic that Euroland’s regulators are calling for much more radical steps than Washington is willing to take. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicolas Sarkozy are calling for more regulation and for limits on executive compensation even as the Obama administration continues to argue that such limits would constrain the financial sector’s ability to retain the “best and the brightest”. If the bozos that created this crisis are the best that Wall Street can find, it would be better to shut down the US financial system than to keep them in charge. It is doubly ironic that Nigeria (a country that normally would not come immediately to mind as a role model) has actually charged the leadership of five of its major banks with crimes. Each of these banks had received government money in a bailout, and the CEOs stand accused of “fraud, giving loans to fake companies, lending to businesses they had a personal interest in and conspiring with stockbrokers to drive up share prices.”

Isn’t that normal business practice for Wall Street banks favored by Ben Bernanke and Timothy Geithner? It is time to get the NY Fed out of Goldman’s back pocket, and to permanently downsize the role played by Wall Street and the Fed in our economic system.

A few years ago, textbooks had traditionally presented monetary policy as a choice between targeting the quantity of money or the interest rate. It was supposed that control of monetary aggregates could be achieved through control over the quantity of reserves, given a relatively stable “money multiplier”. (Brunner 1968; Balbach 1981) This even led to some real world attempts to hit monetary growth targets—particularly in the US and the UK during the early 1980s. However, the results proved to be so dismal that almost all economists have come to the conclusion that at least in practice, it is not possible to hit money targets. (B. Friedman 1988) These real world results appear to have validated the arguments of those like Goodhart (1989) in the UK and Moore (1988) in the US that central banks have no choice but to set an interest rate target and then accommodate the demand for reserves at that target. Hence, if the central bank can indeed hit a reserve target, it does so only through its decision to raise or lower the interest rate to lower or raise the demand for reserves. Thus, the supply of reserves is best thought of as wholly accommodating the demand, but at the central bank’s interest rate target.

Why does the central bank necessarily accommodate the demand for reserves? There are at least four different answers. In the US, banks are required to hold reserves as a ratio against deposits, according to a fairly complex calculation. In the 1980s, the method used was changed from lagged to contemporaneous reserve accounting on the belief that this would tighten central bank control over loan and deposit expansion. As it turns out, however, both methods result in a backward looking reserve requirement: the reserves that must be held today depend to a greater or lesser degree on deposits held in the fairly distant past. As banks cannot go backward in time, there is nothing they can do about historical deposits. Even if a short settlement period is provided to meet reserve requirements, the required portfolio adjustment could be too great—especially when one considers that many bank assets are not liquid. Hence, in practice, the central bank automatically provides an overdraft—the only question is over the “price”, that is, the discount rate charged on reserves. In many nations, such as Canada and Australia, the promise of an overdraft is explicitly given, hence, there can be no question about central bank accommodation.

A second, less satisfying, answer is often given, which is that the central bank must operate as a lender of last resort, meaning that it provides reserves in order to preserve stability of the financial system. The problem with this explanation is that while it is undoubtedly true, it applies to a different time dimension. The central bank accommodates the demand for reserves day-by-day, even hour-by-hour. It would presumably take some time before refusal to accommodate the demand for reserves would be likely to generate the conditions in which bank runs and financial crises begin to occur. Once these occurred, the central bank would surely enter as a lender of last resort, but this is a different matter from the daily “horizontal” accommodation.

The third explanation is that the central bank accommodates reserve demand in order to ensure an orderly payments system. This might be seen as being closely related to the lender of last resort argument, but I think it can be more plausibly applied to the time frame over which accommodation takes place. Par clearing among banks, and more importantly par clearing with the government, requires that banks have access to reserves for clearing. (Note that deposit insurance ultimately makes the government responsible for check clearing, in any event.)

The final argument is that because the demand for reserves is highly inelastic, and because the private sector cannot increase the supply, the overnight interest rate would be highly unstable without central bank accommodation. Hence, relative stability of overnight rates requires “horizontal” accommodation by the central bank. In practice, empirical evidence of relatively stable overnight interest rates over even very short periods of time supports the belief that the central bank is accommodating horizontally.

We can conclude that the overnight rate is exogenously administered by the central bank. Short-term sovereign debt is a very good substitute asset for overnight reserve lending, hence, its interest rate will closely track the overnight interbank rate. Longer-term sovereign rates will depend on expectations of future short term rates, largely determined by expectations of future monetary policy targets. Thus, we can take those to be mostly controlled by the central bank as well, as it could announce targets far into future and thereby affect the spectrum of rates on sovereign debt.

Posted in L. Randall Wray, Monetary policy, Uncategorized

By L. Randall Wray [via CFEPS]

Japan presents a somewhat different case, because it operates with a zero overnight rate target. This is maintained by keeping some excess reserves in the banking system. The Bank of Japan can always add more excess reserves to the system since it is satisfied with a zero rate. However, from the perspective of banks, all that “pumping liquidity” into the system means is that they hold more non-earning reserves and fewer low-earning sovereign bills and bonds. There is no reason to believe that this helps to fight deflation, and Japan’s long experience with zero overnight rates even in the presence of deflation provides empirical evidence that even where “pumping liquidity” is possible, it has no discernible positive impact. (The US had a similar experience with discount rates at 1% during the Great Depression.) And, to repeat, “pumping liquidity” is not even a policy option for any nation that operates with positive overnight rates.

Can the central bank do anything about deflation? As the overnight interest rate is a policy variable, the central bank is free to adjust the target to fight deflation. However, both theory and empirical evidence provide ambiguous advice, at best. It is commonly believed that a lower interest rate target will stimulate private borrowing and spending—although many years of zero rates in Japan with chronic deflation provide counter evidence. There is little empirical evidence in support of the common belief that low rates stimulate investment. This could be for a variety of reasons: the central bank can lower the overnight rate, but the relevant longer-term rates are more difficult to reduce; most evidence suggests that investment is interest- inelastic; and in a downturn, the expected returns to investment fall farther and faster than market interest rates can be brought down.

Evidence is more conclusive regarding effects of low rates on housing and consumer durables; indeed, recent lower mortgage rates in the US have undoubtedly spurred a refinancing boom that fueled spending on home remodeling and consumer purchases.

Still, this effect must run its course once all the potentially refinanceable mortgages are turned-over. Further, it must be remembered that for every payment of interest there is an interest receipt. Lower rates reduce interest income. It is generally assumed that debtors have higher spending propensities than creditors, hence, the net effect is presumed to be positive. As populations age, it is probable that a greater proportion of the “rentier” class is retired and at least somewhat dependent upon interest income. This could reverse those marginal propensities.

More importantly, if national government debt is a large proportion of outstanding debt, and if the government debt to GDP ratio is sufficiently high, the net effect of interest rate reductions could well be deflationary. This is because the reduction of interest income provided by government could reduce private spending more than lower rates stimulated private sector borrowing. In sum, the central bank can lower overnight rate targets to fight deflation, but it is not clear that this will have a significant effect.

Read the full article here.

Posted in L. Randall Wray, Monetary policy, Uncategorized

By L. Randall Wray [via CFEPS]

WWII generated huge fiscal deficits, and the Fed agreed in 1942 to peg the Treasury bill rate at 3/8 of 1 per cent. The long-term legacy was a large debt stock, enabling the Fed to use bond purchases rather than discount window borrowing to provide reserves. After the war, the Fed was concerned with potential inflation. In 1947 the Treasury agreed to loosen reins on the Fed, which promptly raised interest rates. The Fed continued to lobby for greater freedom to pursue activist monetary policy, resulting in the 1951 Accord, which abandoned the commitment to maintain low government interest costs. Although not announced explicitly, the Fed clearly targeted interest rates for the next three decades to implement countercyclical policy.

In October 1979, Chairman Paul Volcker, announced a major change: the Fed would use the growth rate of M1 as its target, abandoning interest rates. In practice, the Fed calculated total reserves consistent with its money target, then subtracted borrowed reserves to obtain a non-borrowed reserve target to control money growth. However, if the Fed did not provide sufficient non-borrowed reserves, banks would simply turn to the discount window, causing borrowed reserves to rise (and, in turn, cause the Fed to miss its total reserve target). Because required reserves are always calculated with a lag, the Fed could not refuse to provide needed reserves at the discount window. Thus the Fed found reserves could not be controlled. Further, the rate of growth of M1 actually exploded beyond targets in spite of persistently tight monetary policy, demonstrating the Fed could not hit money targets, either. The attempt to target reserves effectively ended in 1982 (after a very deep recession); the attempt to hit M1 growth targets was abandoned in 1986; and the attempt to target growth of broader money aggregates finally came to an official end in 1993.

Current Policy

Since the early 1990s, the Fed has formulated a new operating procedure that is loosely based on the new monetary consensus—the orthodox approach to monetary theory and policy. The Fed’s policy today is based on five key principles:

1. transparency;

2 gradualism;

3. activism;

4. inflation as the only official goal, but the Fed actually targets distribution;

5. neutral rate as the policy instrument to achieve these goals.

Briefly, over the past decade the Fed has increased “transparency”, telegraphing its moves well in advance and announcing interest rate targets. It also follows a course of gradualism–small adjustments of interest rates (usually 25 to 50 basis points) over several years to achieve ultimate targets. Ironically, by telegraphing its intentions long in advance, and by using a series of small interest rate adjustments, the Fed creates expectations of continued rate hikes (or declines) that it feels compelled to make—for otherwise it can jolt markets—even if economic circumstances change.

These developments have occurred during a long-term trend toward policy activism, contrasting markedly with Milton Friedman’s famous call for rules rather than discretion. The policy instrument used by the Fed is something called a “neutral rate” that varies across countries and through time—an interest rate that is supposed to be consistent with stable GDP growth at full capacity. The neutral rate cannot be recognized until achieved, so it cannot be announced in advance—which is somewhat in conflict with the adoption of transparency. In consequence, the Fed must frequently and actively adjust the fed funds rate hoping to find the neutral rate. But, as Friedman long ago warned, an activist policy has just as much chance of destabilizing the economy as it does to stabilize the economy—matters are made worse when activist policy is guided by invisible neutral rates and fickle market expectations that are fueled by the Fed’s own public musings.

Finally, the Fed claims that its chief concern is inflation. Actually the Fed does target asset prices and income shares, and it shows a strong bias against labor and wages. It will allow strong economic growth and even rising prices, so long as employment remains sluggish and wages do not rise. When, however, the Fed fears that wages might rise, it raises interest rates. Further, there is evidence from transcripts of secret Fed deliberations that it does pay attention to asset prices. Indeed, one of the reasons for rate hikes in 1994 was a desire to “prick” the equity market’s “bubble”. It is probable that rate hikes at the beginning of 2000 were designed to slow the growth of stock prices; and rate hikes that began in 2004 may have been geared to slow real estate speculation.

Chairman Greenspan has been credited with masterful management of monetary policy through the Clinton-era “goldilocks” boom of the 1990s, the recession at the end of the decade, and the economic recovery after 2001. Still, critics note a number of missteps: Greenspan said the stock market was “irrationally exuberant” as early as 1994 (six years before it peaked) and various attempts by the Fed to cool it failed; after stocks crashed in 2000, Greenspan denied it is possible to identify asset price bubbles; the Fed frequently forecast inflationary pressures that never arrived; and sometimes (including summer of 2004) appeared to raise rates when labor markets were weak, while in other cases it seemed to wait too long to lower rates in recession.

Central Banking Today

By their own admission, most central banks now operate with an interest rate target. To hit a non-zero target, the Fed adds or drains reserves to ensure that banks have the amount of reserves desired (or required in nations like the US with official reserve requirements). Reserves are added through discount window loans, purchases of government bonds, and purchases of gold, foreign currencies, or private sector financial assets. To drain reserves, the central bank reverses these actions. It is actually quite easy to determine whether the banking system faces excess or deficient reserves: the overnight rate moves away from target, triggering an offsetting reserve add or drain by the central bank. Central banks also supervise banks and other financial institutions, engage in lender of last resort activities (a bank in financial difficulty may not be able to borrow reserves in the private lending market even if aggregate reserves are sufficient), and occasionally adopt credit controls, usually on a temporary basis. We will ignore these types of activities as of secondary interest.

When the operating procedure is laid bare, it is obvious that views about controlling reserves, or sterilization of international capital flows, or central bank “financing” of treasury deficits by “printing money” are incorrect. If international payments flows or domestic fiscal actions create excess reserves, the central bank has no choice but to drain the excess–or the overnight rate falls toward zero. On the other hand, if international payments flows or domestic fiscal actions leave banks with insufficient reserves, overnight rates rise above target. For this reason, the quantity of reserves is never discretionary.

Likewise, the view that a central bank might choose to “print money” to finance a budget deficit is flawed. In practice, modern sovereign governments spend by crediting bank accounts and tax by debiting them. Clearing with the government takes place using reserves, that is, on the accounts of the central bank. Deficits lead to net credits of reserves; if excessive, they are drained through bond sales. These activities are coordinated with the Treasury, which issues new bonds in step (whether before or after is not material) with deficit spending. This is because the central bank would run out of bonds to sell. In countries in which the central bank pays interest on reserves, bond sales are unnecessary because interest-paying reserves serve the same purpose—that is, to ensure the overnight interest rate cannot fall below the target. The important point is that central bank operations are not discretionary, but are required to hit interest rate targets.

In sum, the Fed and other central banks of countries with sovereign currencies have complete policy discretion regarding the overnight interest rate. This does not mean that they do not take into account possible impacts of their target on inflation, unemployment, the trade balance, or the exchange rate. Further, central banks often react to budget deficits by raising the overnight interest rate target. These policy actions are discretionary. But what is not discretionary is the quantity of reserves in a system such as that adopted by the US—where banks do not earn interest on reserves. This is because a shortage causes the interest rate to rise above target; an excess causes it to fall. The Fed is forced to defend its target by intervening—adding or draining reserves. A country like Canada that pays interest on positive reserve holdings (and charges interest on reserve lending) need not drain “excess” reserves—because they are not really excessive. Indeed, there is no real distinction between reserves that pay interest or treasury bills that pay interest—both serve the same purpose of maintaining a positive overnight interest rate, so there is no reason to sell bills to banks to “drain excess reserves” in such countries.

We conclude that central banking policy really boils down to interest rate setting and that calls for controlling reserves or the money supply are misguided. However, it is far from clear that interest rates matter much, especially when transparency and gradualism eliminate the element of surprise. Thus, the view that monetary policy can “fine-tune” the economy is probably in error.

References:

Friedman, Milton. 1969. The Optimal Quantity of Money and Other Essays. Chicago: Aldine.

Wray, L. Randall. Understanding Modern Money: The Key to Full Employment and Price Stability, Edward Elgar Publishing, 1998.

—-. The Fed and the New Monetary Consensus: The Case for Rate Hikes, Part Two Levy Policy Brief No. 80, 2004 December 2004

Posted in L. Randall Wray, Monetary policy, Uncategorized

The Fed chairman Ben Bernanke in his recent op-ed piece argued that “given the current economic conditions, banks have generally held their reserves as balances at the Fed.” This is not surprising since, in uncertain times, banks’ liquidity preference rise sharply which reflects on their desire to increase their holdings of liquid assets, such as reserve balances, on their balance sheets.

However, Bernanke pointed out that “as the economy recovers, banks should find more opportunities to lend out their reserves.” The reasoning behind this argument is the so-called multiple deposit creation in which the simple deposit multiplier relates an increase in reserves to an increase in deposits (Bill Mitchell explains it in more details here and here). This is a misconception about banking lending. It presupposes that given an increase in reserve balances (RBs) and excess reserves, assuming that banks do not want hold any excess reserves (ERs), the multiple increase in deposits generated from an increase in the banking system’s reserves can be calculated by the so-called simple deposit multiplier m = 1/rrr, where rrr is the reserve requirement ratio (let’s say 10%). It tells us how much the money supply (M) changes for a given change in the monetary base (B) i.e. M=mB. In this case, the causality runs from the right-hand side of the equation to the left-hand side. The central bank, through open market operations, increases reserve balances leading to an increase in excess reserves in which banks can benefit by extending new loans: ↑RBs → ↑ER → ↑Loans and ↑Deposits.

However, in the real world, money is endogenously created. Banks do not passively await funds to issue loans. Banks extend loans to creditworthy borrowers to meet the needs of trade. In this process, loans create deposits and deposits create reserves. We can illustrate this using T-account as follows:

The bank makes a new loan (+1000) and at the same time the borrower’s account is credited with a deposit of an equivalent amount of the loan. Thus, “the increase in the money supply is a consequence of increased loan expenditure, not the cause of it.” (Kaldor and Trevithick, 1981: 5)

In order to meet reserve requirements, banks can obtain reserves in secondary markets or they can borrow from Fed via the discount window.

As noted by Kaldor (1985), Minsky (1975), Goodhart (1984), Moore (1988), Wray (1990), Lavoie (1984) to name a few, money is endogenously created. The supply of money responds to changes in the demand for money. Loans create deposits and deposits create reserves as explained here and here. It turns the deposit multiplier on its head. Goodhart (1994) observed that “[a]lmost all those who have worked in a [central bank] believe that [deposit multiplier] view is totally mistaken; in particular, it ignores the implications of several of the crucial institutional features of a modern commercial banking system….’ (Goodhart, 1994:1424).

As Fulwiller put it, “deposit outflows, if they exceed the bank’s RBs, result in overdrafts. Banks clear this via lowest cost available in money markets or from the Fed.” In this case, let us assume that the bank issues some other liability, such as CDs, in order to obtain the 1000 reserves needed for clearing its overdraft at the Fed.

It reverses the orthodox story of the deposit multiplier (M=mB). Banks are accepting the liability of the borrower and they are creating their own liability, which is the demand deposit. In this process, banks create money by issuing its own liability, which is counted as a component of the money supply. Banks do not wait for the appropriate amount of liquid resources to exist to provide new loans to the public. Instead, as Lavoie (1984) noted ‘money is created as a by-product of the loans provided by the banking system’. Wray (1990) puts it best:

“From the bank’s point of view, money demand is indicated by the willingness of the firm to issue an IOU, and money supply is determined by the willingness of the bank to hold an IOU and issue its own liabilities to finance the purchase of the firm’s IOU…the money supply increases only because two parties willingly enter into commitments.” (Wray 1990 P.74)

As showed above, when banks, overall, are in need of more high-powered money (HPM), they can increase their borrowings with the central bank at the discount rate. Reserve requirements (RRs) cannot be used to control the money supply. In fact, RRs increase the cost of the loans granted by banks. As Wray pointed out “in order to hit the overnight rate target, the central bank must accommodate the demand for reserves—draining the excess or supplying reserves when the system is short. Thus, the supply of reserves is best characterized as horizontal, at the central bank’s target rate.” The central bank cannot control even HPM!The latter is provided through government spending (or Fed lending). The central bank can only modify its discount rate or its rate of intervention on the open market.

Bernanke is concerned that the sharp increase in reserve balances “would produce faster growth in broad money (for example, M1 or M2) and easier credit conditions, which could ultimately result in inflationary pressures.” He is considering the money-price relationship given by the old-fashioned basic quantity theory of money relating prices to the quantity of money based on the equation of exchange (The idea that money is related to price levels and inflation it is not a new idea at all, you can find that, for example, in Hume and other classical economists):

M*V = PQ, where M stands for the money supply (which in the neoclassical model is taken as given, i.e. exogenously determined by monetary policy changes in M), Q is the level of output predetermined at its full employment value by the production function and the operation of a competitive labor market; P is the overall price level and V is the average number of times each dollar is used in transactions during the period. Causality runs from the left-hand side to the right-hand side (nominal output)

According to the monetarist view, under given assumptions, changes in M cause changes in P, i.e. the rate of growth of the money supply (such as M1 and M2) determines the rate of change of the price level. Hence, to avoid high inflations monetary policy should pursue a stable low growth rate in the money supply. The Fed, under Paul Volcker, adopted money targets in October 1979. This resulted in extremely high interest rates, the fed-funds rate was above 20%, the US had double digit unemployment and suffered a deep recession. In addition, the Fed did not hit its money targets. The recession was extremely severe and in 1982 Volker announced that they were abandoning the monetarist experiment. The rate of money growth exploded to as high as 16% p.y, over 5 times what Friedman had recommended, and inflation actually fell (see figure below).

Source: Benjamin Friedman, 1988 :55

The Collapse of the Money-Income and Money-Price Relationships

A closer look at the 1980s and 1990s help us understand the relationship between monetary aggregates such as M1 and M2 and inflation. This is a relationship that did not hold up either in the 1980s nor in the 1990s. As Benjamin Friedman (1988) observed “[a]nyone who had relied on prior credit-based relationships to predict the behavior of income or prices during this period would have made forecasts just as incorrect as those derived from money-based relationships.” (Benjamin Friedman, 1988:63)

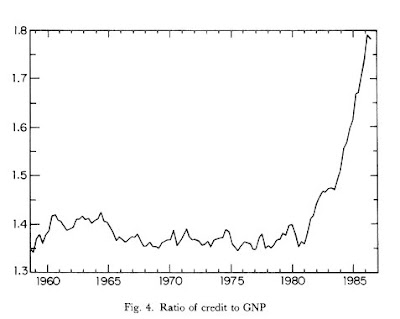

Despite the collapse of the relationship between monetary aggregates and inflation Bernanke still believes that “we must either eliminate these large reserve balances or, if they remain, neutralize any potential undesired effects on the economy.” He noted that “we will need to tighten monetary policy to prevent the emergence of an inflation problem down the road” However, is inflation always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon? The answer is no. The picture below plots the credit-to-GNP ratio. Note that even “the movement of credit during the post-1982 period bore no more relation to income or prices than did that of any of the monetary aggregates.” (Benjamin Friedman, 1988:63, emphasis added)

What about the other monetary aggregates? Benjamin Friedman (1988) pointed out that “[t]he breakdown of long-standing relationships to income and prices has not been confined to the M1 money measure. Neither M2 nor M3, nor the monetary base, nor the total debt of domestic nonfinancial borrowers has displayed a consistent relation- ship to nominal income growth or to inflation during this period.” (ibid, p.62)

Even Mankiw admitted that “[t]he standard deviation of M2 growth was not unusually low during the 1990s, and the standard deviation of M1 growth was the highest of the past four decades. In other words, while the nation was enjoying macroeconomic tranquility, the money supply was exhibiting high volatility. The data give no support for the monetarist view that stability in the monetary aggregates is a prerequisite for economic stability.” Mankiw, 2001: 33)

He concluded that “[i]n February 1993, Fed chairman Alan Greenspan announced that the Fed would pay less attention to the monetary aggregates than it had in the past. The aggregates, he said, ‘do not appear to be giving reliable indications of economic developments and price pressures’… [during the 1990s] increased stability in monetary aggregates played no role in the improved macroeconomic performance of this era.” (Mankiw 2001, 34)

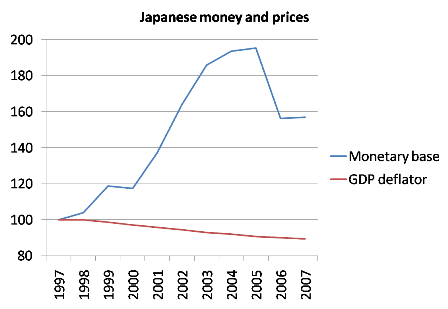

A recent study conducted by the FRBSF also concluded that “there is no predictive power to monetary aggregates when forecasting inflation.” What about the Japanese experience? As the figure below shows, the monetary base exploded but prices actually fell!

Source: Krugman

Source: Krugman

What about the US in the 1930s? The same pattern happened, HPM rose sharply and prices were stable!

Source: Krugman

Chairman Bernanke should learn the basic lesson that money is endogenously created. Money comes into the economy endogenously to meet the needs of trade. Most of the money is privately created in private debt contracts. As production and economic activity expand, money expands. The privately created money is used to transfer purchasing power from the future to the present; buy now, pay latter. It allows people to spend beyond what they could spend out of their income or assets they already have. Money is destroyed when debts are repaid.

Consumer price inflation pressures can be caused by struggles over the distribution of income, increasing costs such as labor costs and raw material costs, increasing profit mark-ups, market power, price indexation, imported inflation and so on. As explained above, monetary aggregates are not useful guides for monetary policy.

Posted in Felipe C. Rezende, Monetary policy, Uncategorized

Tagged Federal Reserve, Felipe C. Rezende, inflation, Monetary policy

Five Unasked Questions About the Stress Tests

1. Why will these (weak) stress tests lead to more realistic evaluations than the (far tougher) stress tests that Congress mandated for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac?

Congress mandated a purportedly “stringent” stress test for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac over a decade ago. It required them to have adequate capital to withstand the simultaneous onslaught of severe credit, interest rate and operational risks that continued for 10 years. The current Treasury test concentrates solely on credit risk and assumes it ends after two years. How well did the far more stringent Fannie and Freddie stress tests work? In August 2008, Freddie reported that “even [our] most severe stress tests [show] losses … less than $5 billion.” It failed in September. Actual losses: 20 to 40 times greater.

2. Where else were stress tests used?

Stress tests were used for the Rating Agencies, IndyMac, and AIG. The Rating Agencies’ stress tests gave AAA ratings to toxic waste. Actual losses: more than an order of magnitude greater than those predicted by the stress tests. IndyMac sold over $200 billion of “liar’s loans.” Actual losses: 160 times greater than its tests. AIG (2007): “It is hard for us, without being flippant, to even see a scenario within any kind of realm of reason that would see us losing one dollar in any of those [CDS] transactions.” AIG (2008): “Using a severe stress test … losses could go as high as $900 million.” Actual losses: 200 times greater.

3. When did Geithner begin to claim that stress tests were the keys to safe operation?

As president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, in a speech in 2004, he first praised stress tests. He was the principal regulator of many of the largest bank holding companies in the U.S. Every large bank has long used stress tests – and Geithner’s Federal Reserve examiners reviewed their stress tests. The big banks’ stress tests on nonprime loans and derivatives failed, and the Federal Reserve examiners consistently failed to understand the failures.

4. How can you conduct a stress test without reviewing the bad mortgage assets’ (missing) underlying loan files?

A Standard & Poor’s (S&P) memorandum recently unearthed reveals the sad truth about how non-prime collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) were purchased, pooled, rated and sold: ”Any request for loan level tapes is TOTALLY UNREASONABLE!!!. … Most investors don’t have it and can’t provide it. … we MUST produce a credit estimate. … It is your responsibility to provide those credit estimates and your responsibility to devise some method for doing so.” The email message is from a senior S&P manager to the professional rater. The word “investors” means the entity that created the CDOs. One cannot evaluate loan quality or losses accurately without reviewing a significant sample of the underlying loan files. The banks and the regulators virtually never do this. They did not do this during the stress tests. They do not even have access to the files that they need to review.

5. How can you ignore fraud losses during an “epidemic” of mortgage fraud?

The FBI began testifying publicly in September 2004 about the “epidemic” of mortgage fraud. It has also stated that lending insiders participated in 80 percent of mortgage fraud losses. The presence of massive fraud losses means primarily produced by lenders makes it absurd to rely (as Treasury did in its stress tests) on the lenders’ loss evaluations. Stress tests produce fictional results that massively understate real losses and produce complacency.

Comments Off on Do banks need more capital?

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged Control Fraud, Federal Reserve, Financial system