By L. Randall Wray [via CFEPS]

Interpretations of the Fed’s policy during the 1930s range from the Monetarist claim that the Fed reduced the money supply, causing the financial crisis and Great Depression, to the more common belief that the Fed’s inaction made things worse. Actually, the Fed intervened immediately, buying $125 million of Treasury securities on the day of the stock market crash– nearly doubling Fed holdings in one day. The New York Fed also opened its discount window to New York banks that were helping correspondent banks. During the early months of the crisis, the Fed continued to meet currency demand and used open market operations to stabilize interest rates. However, by autumn 1931 gold outflows increased, leading the Fed to raise discount rates to protect gold reserves. The money supply (and reserves) was shrinking not because of Fed policy, but because banks could not find worthy borrowers. In truth, there was little that monetary policy could do; recovery would require fiscal stimulus, which finally came with the New Deal and WWII.

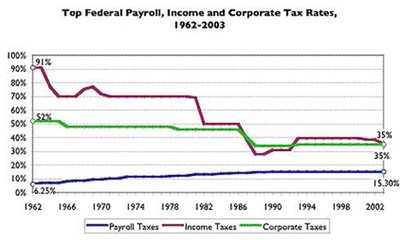

WWII generated huge fiscal deficits, and the Fed agreed in 1942 to peg the Treasury bill rate at 3/8 of 1 per cent. The long-term legacy was a large debt stock, enabling the Fed to use bond purchases rather than discount window borrowing to provide reserves. After the war, the Fed was concerned with potential inflation. In 1947 the Treasury agreed to loosen reins on the Fed, which promptly raised interest rates. The Fed continued to lobby for greater freedom to pursue activist monetary policy, resulting in the 1951 Accord, which abandoned the commitment to maintain low government interest costs. Although not announced explicitly, the Fed clearly targeted interest rates for the next three decades to implement countercyclical policy.

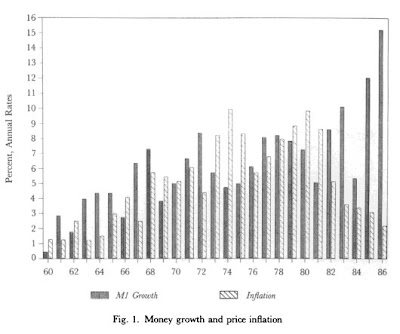

In October 1979, Chairman Paul Volcker, announced a major change: the Fed would use the growth rate of M1 as its target, abandoning interest rates. In practice, the Fed calculated total reserves consistent with its money target, then subtracted borrowed reserves to obtain a non-borrowed reserve target to control money growth. However, if the Fed did not provide sufficient non-borrowed reserves, banks would simply turn to the discount window, causing borrowed reserves to rise (and, in turn, cause the Fed to miss its total reserve target). Because required reserves are always calculated with a lag, the Fed could not refuse to provide needed reserves at the discount window. Thus the Fed found reserves could not be controlled. Further, the rate of growth of M1 actually exploded beyond targets in spite of persistently tight monetary policy, demonstrating the Fed could not hit money targets, either. The attempt to target reserves effectively ended in 1982 (after a very deep recession); the attempt to hit M1 growth targets was abandoned in 1986; and the attempt to target growth of broader money aggregates finally came to an official end in 1993.

Current Policy

Since the early 1990s, the Fed has formulated a new operating procedure that is loosely based on the new monetary consensus—the orthodox approach to monetary theory and policy. The Fed’s policy today is based on five key principles:

1. transparency;

2 gradualism;

3. activism;

4. inflation as the only official goal, but the Fed actually targets distribution;

5. neutral rate as the policy instrument to achieve these goals.

Briefly, over the past decade the Fed has increased “transparency”, telegraphing its moves well in advance and announcing interest rate targets. It also follows a course of gradualism–small adjustments of interest rates (usually 25 to 50 basis points) over several years to achieve ultimate targets. Ironically, by telegraphing its intentions long in advance, and by using a series of small interest rate adjustments, the Fed creates expectations of continued rate hikes (or declines) that it feels compelled to make—for otherwise it can jolt markets—even if economic circumstances change.

These developments have occurred during a long-term trend toward policy activism, contrasting markedly with Milton Friedman’s famous call for rules rather than discretion. The policy instrument used by the Fed is something called a “neutral rate” that varies across countries and through time—an interest rate that is supposed to be consistent with stable GDP growth at full capacity. The neutral rate cannot be recognized until achieved, so it cannot be announced in advance—which is somewhat in conflict with the adoption of transparency. In consequence, the Fed must frequently and actively adjust the fed funds rate hoping to find the neutral rate. But, as Friedman long ago warned, an activist policy has just as much chance of destabilizing the economy as it does to stabilize the economy—matters are made worse when activist policy is guided by invisible neutral rates and fickle market expectations that are fueled by the Fed’s own public musings.

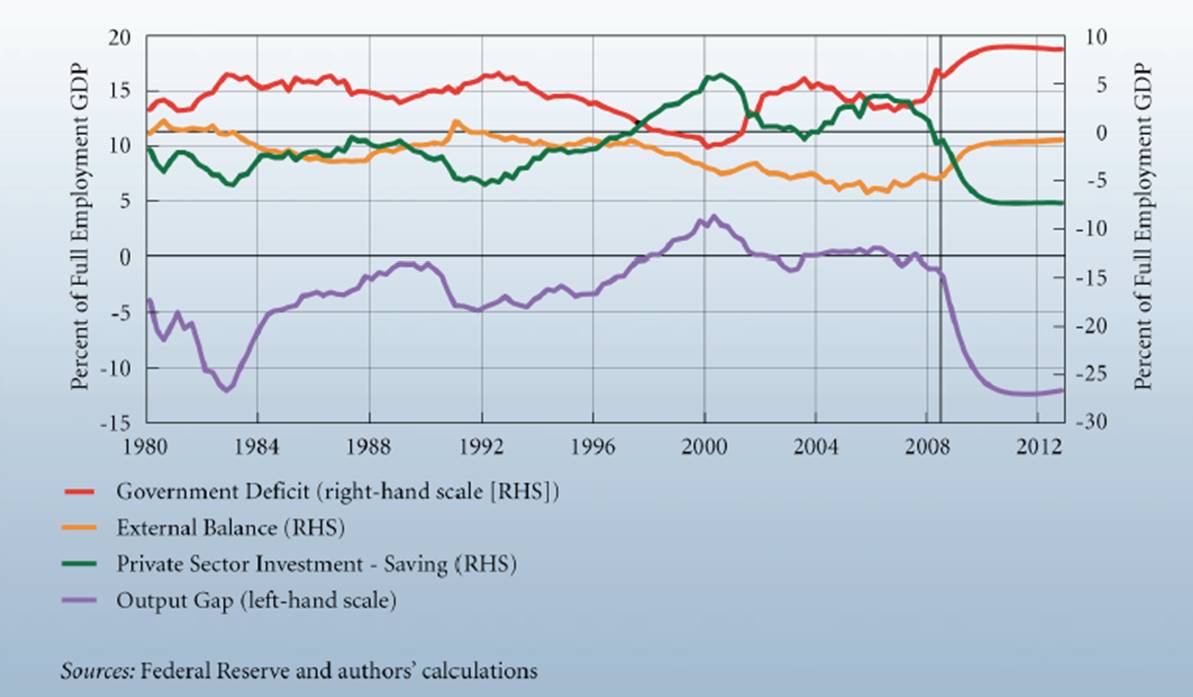

Finally, the Fed claims that its chief concern is inflation. Actually the Fed does target asset prices and income shares, and it shows a strong bias against labor and wages. It will allow strong economic growth and even rising prices, so long as employment remains sluggish and wages do not rise. When, however, the Fed fears that wages might rise, it raises interest rates. Further, there is evidence from transcripts of secret Fed deliberations that it does pay attention to asset prices. Indeed, one of the reasons for rate hikes in 1994 was a desire to “prick” the equity market’s “bubble”. It is probable that rate hikes at the beginning of 2000 were designed to slow the growth of stock prices; and rate hikes that began in 2004 may have been geared to slow real estate speculation.

Chairman Greenspan has been credited with masterful management of monetary policy through the Clinton-era “goldilocks” boom of the 1990s, the recession at the end of the decade, and the economic recovery after 2001. Still, critics note a number of missteps: Greenspan said the stock market was “irrationally exuberant” as early as 1994 (six years before it peaked) and various attempts by the Fed to cool it failed; after stocks crashed in 2000, Greenspan denied it is possible to identify asset price bubbles; the Fed frequently forecast inflationary pressures that never arrived; and sometimes (including summer of 2004) appeared to raise rates when labor markets were weak, while in other cases it seemed to wait too long to lower rates in recession.

Central Banking Today

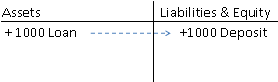

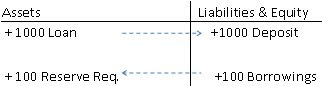

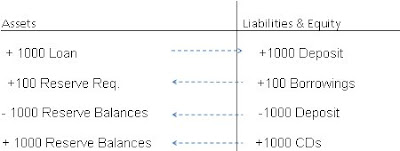

By their own admission, most central banks now operate with an interest rate target. To hit a non-zero target, the Fed adds or drains reserves to ensure that banks have the amount of reserves desired (or required in nations like the US with official reserve requirements). Reserves are added through discount window loans, purchases of government bonds, and purchases of gold, foreign currencies, or private sector financial assets. To drain reserves, the central bank reverses these actions. It is actually quite easy to determine whether the banking system faces excess or deficient reserves: the overnight rate moves away from target, triggering an offsetting reserve add or drain by the central bank. Central banks also supervise banks and other financial institutions, engage in lender of last resort activities (a bank in financial difficulty may not be able to borrow reserves in the private lending market even if aggregate reserves are sufficient), and occasionally adopt credit controls, usually on a temporary basis. We will ignore these types of activities as of secondary interest.

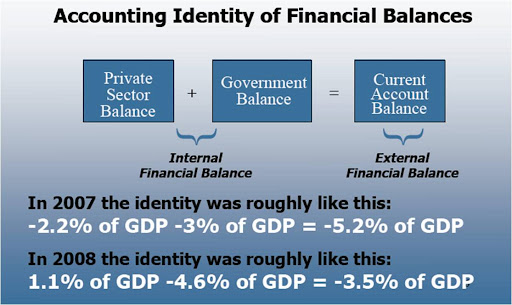

When the operating procedure is laid bare, it is obvious that views about controlling reserves, or sterilization of international capital flows, or central bank “financing” of treasury deficits by “printing money” are incorrect. If international payments flows or domestic fiscal actions create excess reserves, the central bank has no choice but to drain the excess–or the overnight rate falls toward zero. On the other hand, if international payments flows or domestic fiscal actions leave banks with insufficient reserves, overnight rates rise above target. For this reason, the quantity of reserves is never discretionary.

Likewise, the view that a central bank might choose to “print money” to finance a budget deficit is flawed. In practice, modern sovereign governments spend by crediting bank accounts and tax by debiting them. Clearing with the government takes place using reserves, that is, on the accounts of the central bank. Deficits lead to net credits of reserves; if excessive, they are drained through bond sales. These activities are coordinated with the Treasury, which issues new bonds in step (whether before or after is not material) with deficit spending. This is because the central bank would run out of bonds to sell. In countries in which the central bank pays interest on reserves, bond sales are unnecessary because interest-paying reserves serve the same purpose—that is, to ensure the overnight interest rate cannot fall below the target. The important point is that central bank operations are not discretionary, but are required to hit interest rate targets.

In sum, the Fed and other central banks of countries with sovereign currencies have complete policy discretion regarding the overnight interest rate. This does not mean that they do not take into account possible impacts of their target on inflation, unemployment, the trade balance, or the exchange rate. Further, central banks often react to budget deficits by raising the overnight interest rate target. These policy actions are discretionary. But what is not discretionary is the quantity of reserves in a system such as that adopted by the US—where banks do not earn interest on reserves. This is because a shortage causes the interest rate to rise above target; an excess causes it to fall. The Fed is forced to defend its target by intervening—adding or draining reserves. A country like Canada that pays interest on positive reserve holdings (and charges interest on reserve lending) need not drain “excess” reserves—because they are not really excessive. Indeed, there is no real distinction between reserves that pay interest or treasury bills that pay interest—both serve the same purpose of maintaining a positive overnight interest rate, so there is no reason to sell bills to banks to “drain excess reserves” in such countries.

We conclude that central banking policy really boils down to interest rate setting and that calls for controlling reserves or the money supply are misguided. However, it is far from clear that interest rates matter much, especially when transparency and gradualism eliminate the element of surprise. Thus, the view that monetary policy can “fine-tune” the economy is probably in error.

References:

Friedman, Milton. 1969. The Optimal Quantity of Money and Other Essays. Chicago: Aldine.

Wray, L. Randall. Understanding Modern Money: The Key to Full Employment and Price Stability, Edward Elgar Publishing, 1998.

—-. The Fed and the New Monetary Consensus: The Case for Rate Hikes, Part Two Levy Policy Brief No. 80, 2004 December 2004