[Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3] [Part 4] […]

This five part series will explore at length (warning!) and in detail (another warning—wonk alert!) the MMT perspective on the debt ratio and fiscal sustainability. While the approach suggests a macroeconomic policy mix and strategies for both fiscal and monetary policies that most neoclassical economists currently believe are unsustainable, ultimately the MMT preference for a significant role for fiscal policy in macroeconomic stabilization is shown to be consistent with traditional neoclassical views on fiscal sustainability.

This fifth and final (!) part applies functional finance to CBO’s projections of the government’s long-term budget outlook and then offers concluding remarks for the entire series.

Functional Finance, the Debt Ratio, and CBO’s Projections

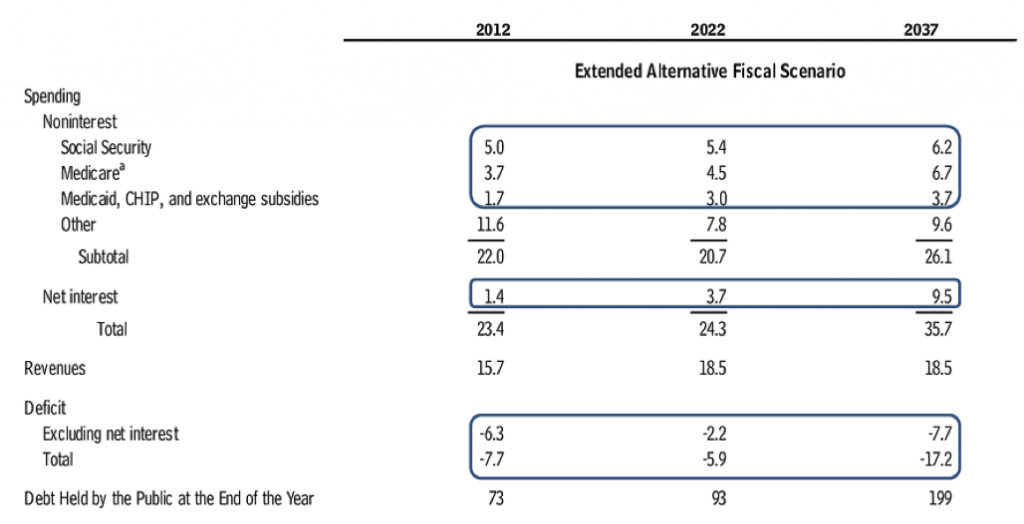

Finally, let’s apply this functional finance approach to the fiscal/monetary policy mix to the current debate over future entitlements and the recent projections by CBO. As shown in Table 5 taken from CBOs own projections that it deemed most likely, the debt ratio is projected to rise to 199% by 2037 as a result of total budget balance deficits that rise to 17.2% of GDP and primary deficits that are 7.7% of GDP. The primary deficits arise largely from the assumption that entitlement spending (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid) rise by 6.2% of GDP. As a result of the primary deficits, the debt service ratio rises from the current 1.4% of GDP to 9.5% of GDP.

Table 5

From the neoclassical perspective, this is a classic example of non-Ricardian fiscal policy, which explains why neoclassical economists are so concerned. Regardless of whether they are deficit hawks or deficit doves, they view this in the same way for the most part, as most deficit doves are simply deficit hawks that aren’t in as much of a hurry. At any rate, the non-Ricardian chain of causation is at work here—exogenous fiscal policy drives primary deficits too high and debt service then rises as a result; not shown by CBO is the fear of many that long before this happens, the rise in the debt ratio will encourage bond vigilantes to push debt service still higher long before 2037. Of course, CBO doesn’t project estimates of inflation that might result from this outcome. Oddly, CBO assumes the economy will be at full employment with stable inflation for these estimates, which enables it to project deficits and so forth as a percent of GDP.

A functional finance approach, on the other hand, would require CBO to instead provide estimates of the impacts on inflation that would result. Obviously, one is supposed to assume that these outcomes would be inflationary, but in that case debt service does not rise as a percent of GDP as nominal GDP simply rises with debt service. Or, absent inflation, one is then probably supposed to assume default, perhaps again as a result of bond vigilantes (the best refutation of this is here, though I’ve always been partial to this one). At any rate, without an estimate of an economically significant increase in inflation, it’s unclear at least in theory what the macroeconomic outcome would be. The only mention is CBOs brief discussion of the “dangers” of deficits is largely described in terms of rising interest rates, which is inapplicable given that interest on the national debt is a monetary policy variable.

From the functional finance view, CBO’s analysis is a clear case of assuming what I’ve called unsustainable monetary policy, as it assumes real GDP will grow at 2.2% while the average real interest rate on the national debt will be 2.7% all in the presence of large primary deficits. That is, if CBO’s projections of non-interest spending relative to revenues turned out to be accurate, then why would a self-described inflation targeting central bank allow interest rates on the national debt to remain above GDP growth and thereby create rising inflation via unbounded increases in debt service?

One could suggest as in the Godley and Lavoie functional finance rule that some combination of government spending and taxation adjustments occur in kind to reduce the primary surplus enough to avoid a rising debt ratio regardless of the interest rate. This shows how functional finance—while it is an alternative approach to fiscal policy for stabilization purposes and relative to the “sound finance” approach—is simply a different angle on what economists are already urging fiscal policymakers to do when it comes to fiscal sustainability. The difference is the focus is on pursuing a “neutral” budget balance that provides full utilization of capacity without rising inflation, not budget cuts for their own sake or out of fear of bond vigilantes.

This is why estimates of inflationary impacts of the projections of primary deficits in Table 5 are so important—will they result in an additional 2% inflation? 5%? 10%? 20? 100%? CBO’s methodological approach in fact provides no information on how much primary deficit reduction—if any—is needed in the future absent accompanying projections of the private sector’s desired net saving at full capacity utilization relative to projected deficits for the same years and some guidance on how these will affect macroeconomic variables.

Beyond this, even from within the neoclassical paradigm the focus on budget cutting is off the mark, as many have already pointed out. Given that CBO projects private health care spending will rise on average at a pace that is 1.6% faster than GDP growth—which themselves are driving the estimated growth in Medicare and Medicaid spending—aside from the obvious unsustainability of this assumption, CBO somehow neglects to point out that this will bankrupt much of the private sector long before the feared government deficits are projected to emerge. And in that case, a larger government deficit will be necessary for a “neutral” budget balance to be achieved. Stock-flow consistency matters, unfortunately for CBO. As a result, cutting government healthcare programs obviously doesn’t solve the problem of less affordable private healthcare for the poor, elderly, and in this case the middle class as well; it makes it worse (again, obviously).

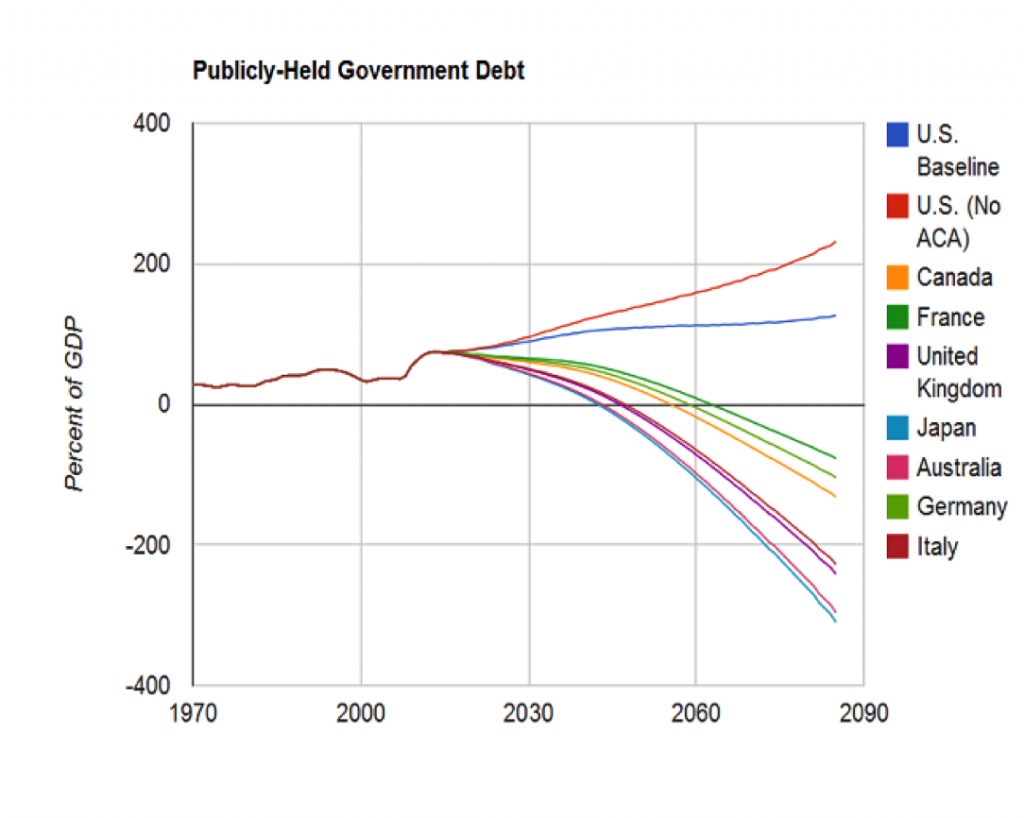

Once this is understood, as increasing numbers now do, the only possible solution is to reduce the growth in private healthcare costs. Further, others such as the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) have shown that modest reductions in aggregate spending on healthcare as a percent of GDP to bring the US in line with the nations spending the next highest amounts as a percent of their GDP (like France and Australia) entirely eliminate CBO’s projected increases in primary deficits, government debt service, and the debt ratio. Figure 11—from the CEPR link above—shows how CBO’s debt ratio projections would look if total healthcare spending in the US as a percent of GDP was in line with that in other countries. In short, the U.S. has a private healthcare crisis—which is still not fixed, unfortunately, whatever your view of Obamacare might be—not an imminent entitlement crisis or an imminent public debt crisis.

Figure 11

CBO’s Projected Debt Ratio (Red) vs. CBO’s Projections with Reduced US Healthcare Spending to Equal % of GDP in Other Countries (CEPR’s calculations)

Conclusion

In the end, what have we learned from all this?

First, the appropriate measure of the national debt for discussing fiscal sustainability is the debt held by private investors. As it stands now, the US debt ratio is a very modest 60% of GDP.

Second, increases in the debt ratio and debt service traditionally deemed unsustainable are driven by the assumption that interest rates are higher than GDP growth.

Third, interest rates on the national debt are a policy variable for a currency-issuing government under flexible exchange rates, and consistent with this interest on the national debt has averaged less than GDP growth in the post World War II era aside from the 1979-2000 period in which monetary policy makers targeted higher interest rates.

Fourth, the neoclassical perspective on the macroeconomic policy mix is probably both inapplicable and untenable; there are good reasons to run a permanently low interest rate monetary policy coupled with a functional finance-driven fiscal policy, and these two together can be perfectly consistent with fiscal sustainability as well as full capacity utilization and low inflation. At the very least, monetary policy should account for an appropriately designed functional finance fiscal policy strategy in its own reaction function.

Fifth, CBO’s long-term debt projections assume a non-Ricardian fiscal policy combined with a central bank setting interest rates on the national debt above GDP growth; these flawed and even inapplicable assumptions of an unsustainable macroeconomic policy mix are the source of the projections of unbounded growth in debt service and the debt ratio that so many fear. But—as more economists are recognizing—the US has a private healthcare crisis, not a national debt crisis. Instead of scaring people with studies that are dead on arrival as a result of faulty assumptions and methodology, CBO and others should focus their attention on potential solutions to growing private healthcare costs and estimating the macroeconomic impacts of specific projected spending plans or proposed budgets (which would require CBO to allocate resources to undertake the highly useful task of developing a detailed, empirically-based macroeconomic model incorporating desired net private saving, capacity utilization, the labor force, inflation, and so forth).

Pingback: Stephanie Kelton-en kezkak | Heterodoxia, ekonomiaz haratago

Pingback: A Plague on All Your Budgets | BirchIndigo