[Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3] […] [Part 5]

This five part series will explore at length (warning!) and in detail (another warning—wonk alert!) the MMT perspective on the debt ratio and fiscal sustainability. While the approach suggests a macroeconomic policy mix and strategies for both fiscal and monetary policies that most neoclassical economists currently believe are unsustainable, ultimately the MMT preference for a significant role for fiscal policy in macroeconomic stabilization is shown to be consistent with traditional neoclassical views on fiscal sustainability.

This fourth part integrates the content of the first three parts with the functional finance strategy for fiscal policy. Warning again—this part is the longest and most detailed of the four.Functional Finance and Fiscal Sustainability

We reach the point now where we can integrate the concept of fiscal sustainability—i.e., convergence or at least bounded growth of debt service—with functional finance. In order to do that, though, we first need a brief digression on the concept of Ricardian fiscal policy (see Pavlina Tcherneva’s paper for more on the MMT view of this). The New Consensus view that came to dominate neoclassical economics in the 2000s argued for a macroeconomic policy mix in which monetary policy managed the economy and targeted inflation through a Taylor Rule-like strategy for adjusting the interest rate and fiscal policy largely got out the way by simply adhering to its intertemporal budget constraint by setting current and future taxes and spending such that the debt ratio does not rise without bound (a bit more on the policy mix here). Fiscal policy that achieves this is called Ricardian by neoclassicals. A Ricardian fiscal policy does not interfere with the central bank’s management of the macroeconomy—in most cases it preferably passive and responds endogenously to its intertemporal budget constraint only.

On the other hand, when fiscal policy is set exogenously to run permanent surpluses inconsistent with keeping the debt ratio from rising without bound, this is called non-Ricardian fiscal policy. This obviously does interfere with the central bank’s attempts to manage the macroeconomy. This is because raising the interest rate to slow inflation in the non-Ricardian scenario results in more aggregate demand through government debt service, or the government “printing money” to avoid defaulting, and thus more inflation.

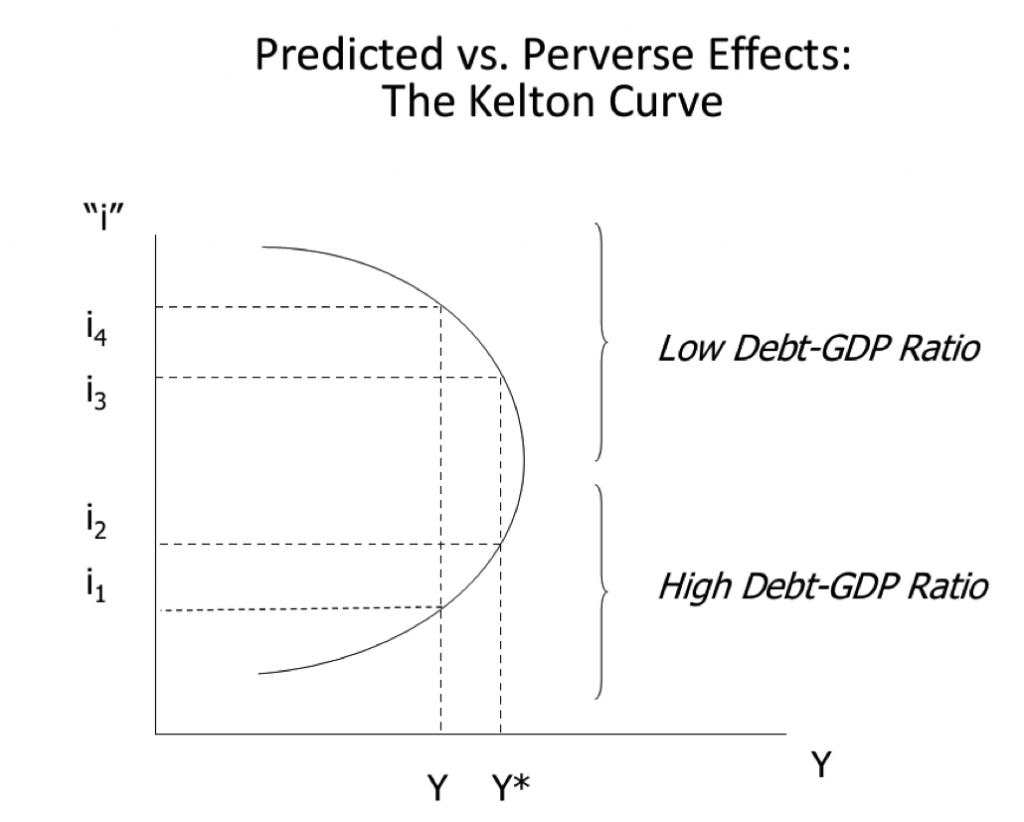

While this understanding of the monetary/fiscal policy mix is recognized in literature on fiscal sustainability, it’s puzzling how often this is neglected in more standard neoclassical analysis of macroeconomic policy effects. Indeed, most any neoclassical analysis of monetary policy shows suggests that interest rates and spending are always negatively related. As explained in 2005 by Stephanie Kelton and Rex Ballinger, often forgotten is the fact that interest payments to the non-government sector are always private sector income, and thus analysis should always incorporate it as such and not save it for special circumstances. Kelton and Ballinger present what we’ve come to call “The Kelton Curve,” (Figure 6) which shows how the relationship between interest rates and aggregate demand can be “perverse” compared to the more traditional view if rising interest rates raise spending and GDP (as in the move from i1 to i2 that raises Y to Y* in the “High Debt-GDP Ratio scenario).

Figure 6

Note that the Kelton Curve isn’t just about rising rates—it works in reverse (i.e., a move from i2to i1), which is happening right now with record low rates exacerbated by QE operations that reduce the term structure of interest rates by replacing longer-term Treasuries with overnight reserve balances. As Randy Wray explained a few months ago, the negative income effect of low interest rates has been significant in offsetting any fiscal stimulus:

But there’s a darker side. The low deposit rates and the high fees are wiping out savers. I’m not telling you anything you don’t know. You cannot even get half a percentage point on your savings at banks. Sure, your mortgage rate has also fallen, but the net effect has drained consumer’s income. Here’s a quote from a Credit Suisse report:

The side-effect of the Fed’s near-zero interest medicine – the collapse in personal interest income over the last few years. The decline in interest income actually dwarfs estimates of debt service savings. Exhibit 2 compares the evolution of household debt service costs and personal interest income. Both aggregates peaked around $1.4 trillion at roughly the same time – the middle of 2008. According to our analysis of Federal Reserve figures, total debt service – which includes mortgage and consumer servicing costs – is down $206bn from the peak. The contraction in interest income amounts to roughly $407bn from its peak, more than double the windfall from lower debt service.

Let’s put that in perspective. Remember the Obama fiscal stimulus? About $400 billion a year for two years—let’s say almost 3% of GDP. There’s been a big debate about whether it “worked”. Only the truly crazy believe it did not save us from an even worse recession than what we actually went through.

Well, QE is removing an amount of aggregate demand from the economy equal to half of the Obama stimulus. And that is not just for two years—it goes on and on and on, year after year after year, as long as the Fed pursues ZIRP.

So QE is supposed to stimulate the economy by taking 1.5% of GDP away every year?

Just as we learned in the case of Japan—which experimented with ZIRP over the past two decades—extremely low rates take more demand out of the economy than they put in. So the Fed has mistaken the brake for the gas pedal: QE slams on the brakes but the Fed thinks it is sending more gas to the economy. The only thing we can be thankful for is that the Fed is driving a rickshaw, not a Buick. The damage it can do is not lethal.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against ZIRP—I’d have ZIRP all the time—but we need to understand that it does not stimulate the economy.

And we just found out last week that QE completely removed again almost $90 billion of income from the private sector in 2012.

Contrary to neoclassicals that believe there is some rate of interest that will always bring macroeconomic stabilization, MMTers and others (like Horizontalists) think things are much more complex as there are multiple interest rates (which rate(s) should be negative? the New Consensus model has only 1 rate in it), unclear relations between them all (QE3 and its effects on mortgage rates is just one example of the uncertainties), and ultimately multiple, offsetting transmission mechanisms that must be considered (two more are that short-term rates are a cost of production via working capital finance and are perversely related to housing prices as measured by the CPI). In short, a Taylor Rule strategy grossly oversimplifies the real-world context of monetary policy and its applicability has always been seen by MMTers as highly questionable even as there is obviously some truth to the notion that some spending is negatively related to changes in interest rates.

In a world in which the Taylor Rule is a gross oversimplification, a macroeconomic policy mix based solely on monetary policy while fiscal policy makers passively balance the budget intertemporally is also overly simplistic and even destructive. From our perspective, fiscal policy should instead follow a functional finance strategy (see here and here for more) in which it is the outcomes of the fiscal policy stance in terms of unemployment, productivity (living standards), and inflation that matter, not the size of the debt ratio, per se. An appropriately designed functional finance strategy would incorporate both strong automatic stabilizers as well as a “tool kit” of options for dealing with condition in which larger stimulus or restraint are necessary.

By necessity, those details are beyond the scope here—though note that a Taylor Rule is actually just as lacking in detail, if not more so; contrary to the elevated position it has been given by neoclassicals, like functional finance, it is simply a set of principles or criteria to guide policymakers in making real-world strategic decisions based on a particular perspective of how the world works (e.g., raise interest rates when inflation rises or the GDP gap falls, and vice versa; raise interest rates more than the anticipated increase in inflation).

For functional finance, the perspective is that (a) a currency issuing government under flexible exchange rates is not constrained by the more traditional rules of “sound finance” and (b) interest on the national debt is a monetary policy variable, not a rate set by “market forces” or bond vigilantes. As such, in the context of a high debt ratio—and let’s assume the US is a high-debt ratio nation at least for the sake of argument—there are different approaches one can consider. Here are two of them, though these are not mutually exclusive, in fact:

First, Godley and Lavoie design a functional finance fiscal policy “rule” that raises spending when GDP is below potential and cuts it when GDP is above it and also adjusts government spending for the difference between actual and targeted inflation. They show that any rate of interest in this case is consistent with a stable debt ratio and this functional finance “rule.” The key is to recognize that the functional finance rule will always reduce spending whenever the deficit would otherwise be too large for potential GDP or the inflation target to be achieved and that this rule also coincidentally generates a stable debt ratio. If interest rates are high and debt service is rising, as potential GDP comes within site other government spending will fall according to the rule, stabilizing both GDP and for the context here stabilizing the primary deficit at whatever level is consistent with a stable debt ratio. If interest rates are low, the rule enables other spending to rise until potential GDP is reached, but no further. In other words, setting the functional finance strategy as a simple rule like a fiscal policy version of a Taylor rule illustrates that a true functional finance fiscal policy strategy is always Ricardian.

Godley and Lavoie then note that an effective functional finance rule—by carrying out the task of macroeconomic stabilization by itself—would enable monetary policy to focus on the distribution effects of monetary policy. They cite others that have proposed the “fair” rate of interest target, which is the growth rate of productivity plus inflation, that would enable rentiers to earn the same as wage earners (at least in theory). For our purposes here, note how a negative rate of interest—as many neoclassicals suggest is appropriate now—affects distribution; beyond the offsetting effects to fiscal stimulus reported by Wray, the distribution between savers and debtors in the private sector could make a negative nominal rate of interest deflationary, since while neoclassicals believe that negative returns lead savers to spend, in fact most retirees just receive less income in that case on their Treasuries, time deposits, and so forth, and then spend less as a result.

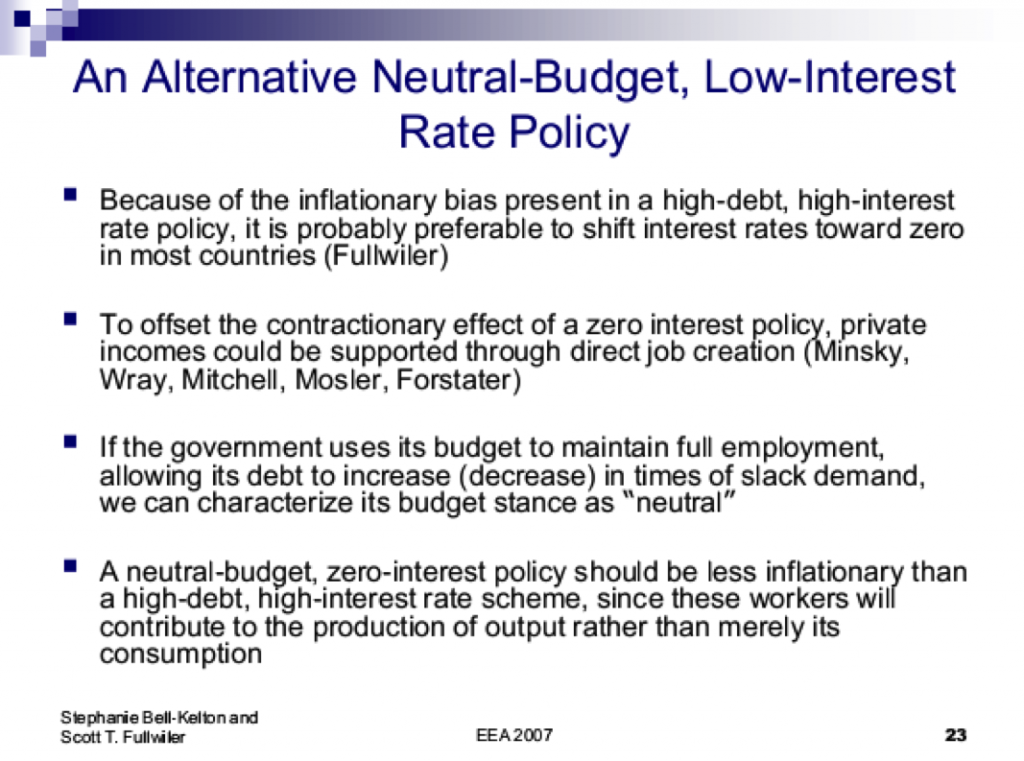

A second view—again, not necessarily mutually exclusive from Godley/Lavoie—is a more purely MMT-inspired one Stephanie Kelton and I presented in 2007, in which a permanently low short-term rate of interest is coupled with a functional finance strategy. The low rate of interest ensures debt service does not rise without bound regardless of the debt ratio or deficit, while the functional finance strategy (as it does in Godley/Lavoie) will offset whatever mix of inflationary or deflationary effects of the low short-term interest rate ultimately prevails (and for retirees, lower portfolio returns—which may or may not occur—there are ways to augment that through fiscal policy, such as Warren Mosler’s recent proposal). Consistent with the Godley/Lavoie rule, we referred to a true functional finance strategy as a “neutral” budget stance, as one could easily extend it to Godley/Lavoie’s functional finance rule to show that there would be a “neutral” functional finance budget stance for any rate of interest on the national debt and thus any debt ratio. A lower interest rate, as we propose here, might be consistent with a political climate in which it might be less politically feasible to reduce a primary deficit quickly in the face of rising debt service. And in that case, a functional finance proponent would refer to unsustainable monetary policy, not unsustainable fiscal policy, since it is far easier to simply reduce the targeted interest rate than to require fiscal action to counter monetary policy in a high debt ratio environment.

Figure 7

(The preference for a low interest rate rather than a “fair” one as they’ve defined it is a technical point that I must leave out here, though I will say that in my discussions with some Horizontalists that favor the latter the two rules aren’t necessarily contradictory since the “fair” rate is not necessarily an overnight rate (it could be a longer-term rate) whereas the MMT proposal does refer to the overnight rate.)

Another reason why the Taylor Rule for monetary policy and balanced intertemporal budget for fiscal policy mix of neoclassicals is problematic is the sector financial balances and stock-flow consistency across sectors of the economy. Anyone reading MMT literature already knows the accounting identity private sector surplus or net saving = government deficit + current account balance.

To briefly summarize, the key point is that absent a current account surplus or government deficit, the domestic private sector cannot net save, which it generally tries to do, at least on average. Thankfully, a currency-issuing government under flexible exchange rates can accommodate this desire by running a budget deficit even if there is no current account surplus, and it can run an even larger deficit if there is a current account deficit to enable the private sector to net save. Not to be confused with saving or private sector investment spending (though many do this, unfortunately), net saving is simply an indicator of how much spending the entire sector is doing relative to the sector’s income; falling net saving tends to be a signal of a move away from Minskyan hedge financing, and vice versa.

An important distinction between monetary and fiscal policy that is often unrecognized is that monetary stimulus “works” through a reduction in private sector net saving whereas fiscal stimulus works through an increase in private sector net saving (see more on this here). That is, cutting interest rates via a Taylor Rule strategy to simulate the economy can only “work” if it results in, for instance, increased business capital spending or increased household spending in both cases relative to income. This ultimately raises tax revenues to the federal government, thereby improving the government’s budget balance and reducing the private sector’s net saving (note—again, just as a technical aside—that private sector saving overall increases with the business capital spending—by accounting definition—but private sector net saving has fallen). For fiscal policy, there is a transfer of income or a tax cut that raises private sector income first—subsequent spending as a result will result in additional tax revenues that somewhat offset the initial increase in net saving for the private sector, but the overall effect is an increase aside from cases of extremely large multiplier effects (which probably only happen in theory).

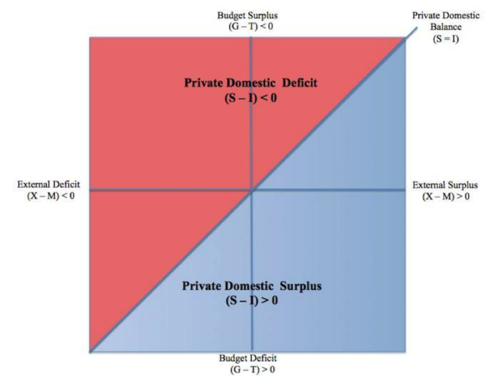

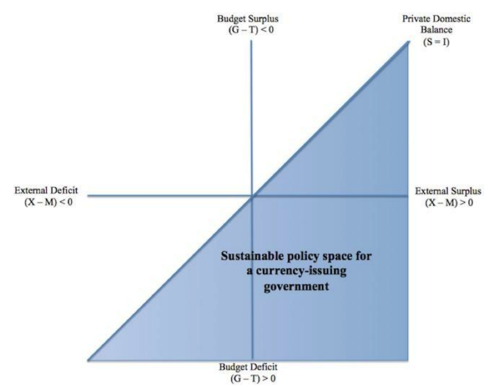

To see how these differing effects on private net saving matter, consider Figures 8 and 9 from Bill Mitchell that present a map of the sector financial balances equation. Figure 8 shows a graph (originally designed by Rob Parenteau here and here) in which the current account is on the horizontal axis, the government’s budget balance is on the vertical, and a diagonal line at the 45-degree point between the two balances is where the private domestic balance is zero. The blue portion below the diagonal is where the private domestic balance is positive, and the red above the diagonal is where the balance is negative. Figure 9 shows that for sustainability of the private sector—from a Minskyan perspective, which analyzes in detail the likelihood of financial distress resulting from the financial positions of private sector agents—on balance the private sector should be in the blue region. If we assume the private sector surplus is to be about 2% of GDP on average—the historical average in the US—then the government’s budget position should be negative unless the current account balance is at least 2% of GDP.

Figure 8

Sector Financial Balances Map

Figure 9

Sustainable Policy Space and the Sector Financial Balances Map

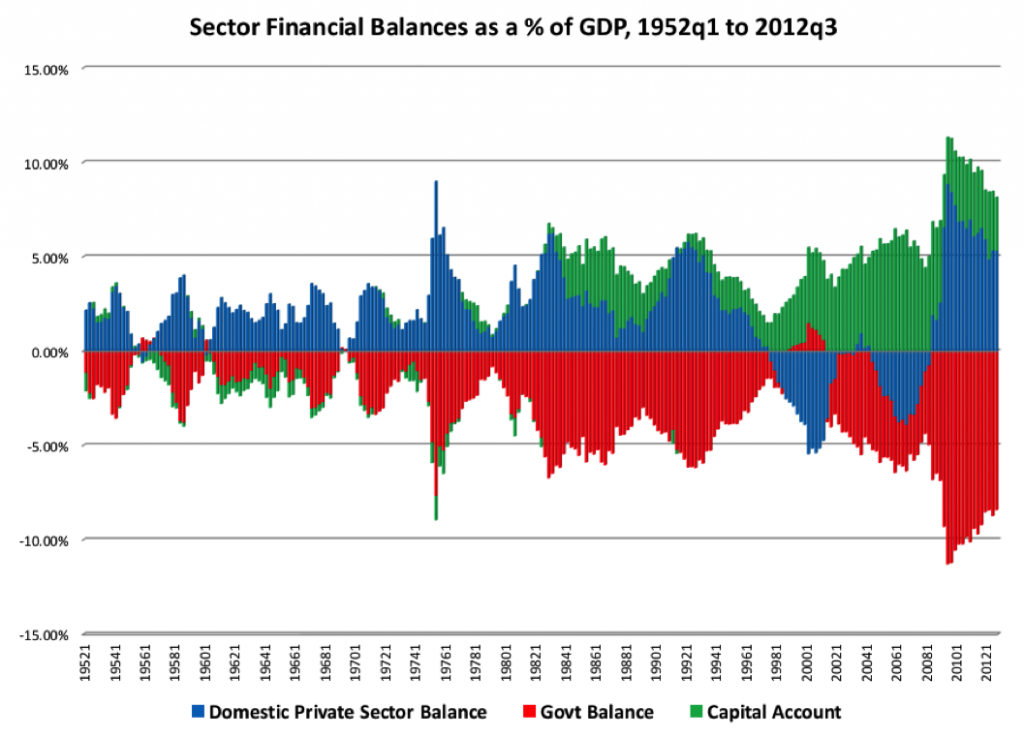

Furthermore, while the private sector might desire a 2% balance on average (for example), in reality this will fluctuate significantly from year to year or even quarter to quarter, as shown in Figure 10 (where the capital account is the opposite of the current account, so all three balances can be shown to generate mirror images around the origin). In other words, because desired private sector net saving at full employment will fluctuate significantly—rising a lot during recessions and falling considerably during expansions—fiscal policy should respond in kind in the opposite direction as a functional finance strategy would suggest. Relying instead on monetary policy only to end a recession requires the private sector to be willing to reduce its balance at the exact time that it typically desires to increase it (and this is not even to mention the acceleration of Minskyan fragility that can result from raising short-term interest rates and thus both the price of refinancing and cost of liabilities to financial institutions in order to halt an expansion that itself might have been the result of monetary policy’s encouragement of greater leverage earlier in the expansion).

Figure 10

In short, again the neoclassical policy mix of a dominant monetary policy driven by a Taylor Rule strategy and a passive fiscal policy balancing its budget intertemporally is found to be inadequate since it is based upon a highly simplified view of the macroeconomy that abstracts from multiple interest rates (the model has only 1), multiple and offsetting transmission mechanisms (again, the model has 1 only), Minskyan fragility (the model assumes no default risk in the private sector, as many have shown), how banks create money endogenously as a matter of accounting (the model assumes loanable funds), and stock-flow consistency across sectors of the economy (the model assumes financial crowding out results from fiscal deficits).

In the real world, fiscal policy must be able to respond to the private sector’s net saving desires at full capacity utilization; a monetary policy strategy based on the Taylor Rule actually does the opposite. This does not necessarily mean that there is no role for monetary policy if one is able to untangle the multiple and offsetting transmission mechanisms (and MMTers see a significant role for monetary policy in dealing with systemic risk and avoiding Minskyan fragility—and thus asset price bubbles—in the financial system, though this is also beyond the scope of this post), but it does mean that even in that case monetary policy should accommodate a functional finance strategy for fiscal policy somewhere in its reaction function used to set its strategy. To do otherwise is to implement a potentially unsustainable monetary policy that threatens the financial stability of the private sector (particularly when the private sector is heavily indebted) or results in direct and potentially perverse effects on public sector debt service relative to macroeconomic policy goals.

In part V, we will consider the implications of functional finance for CBO’s projections of the long-term government budget outlook.

16 responses to “Functional Finance and the Debt Ratio—Part IV”