James K. Galbraith (via Julie Kosterlitz) on “What Is Fiscally — And Politically — ‘Sustainable’?”

James K. Galbraith, Professor of Economics, University of Texas

“Chairman Bernanke may, if he likes, try to define “fiscal sustainability” as a stable ratio of public debt to GDP. But this is, of course, nonsense. It is Ben Bernanke as Humpty-Dumpty, straight from Lewis Carroll, announcing that words mean whatever he chooses them to mean.

Now, we may admit that the power of the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is very great. But would someone please point out to me, the section of the Federal Reserve Act, wherein that functionary is empowered to define phrases just as he likes?

A stable ratio of federal debt to GDP may or may not be the right policy objective. But it is neither more nor less “sustainable,” under different economic conditions, than a rising or a falling ratio.

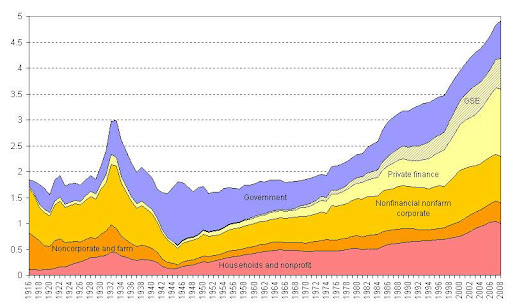

In World War II, from 1940 through 1945, the ratio of US federal debt to GDP rose to about 125 percent. Was this unsustainable? Evidently not. The country won the war, and went on to 30 years of prosperity, during which the debt/GDP ratio gradually fell. Then, beginning in the early 1980s, the ratio started rising again, peaked around 1993, and fell once more.

Thus, a stable ratio of debt to GDP is not a normal feature of modern history. Gradual drift in one direction or the other is normal. There seems no great reason to fear drift in one direction or the other, so long as it is appropriate to the underlying economic conditions.

History has a second lesson. In a crisis, the ratio of public debt to GDP must rise. Why? Because a crisis – and this really is by definition – is a national emergency, and national emergencies demand government action. That was true of the Great Depression, true of war, and true of the Great Crisis we’re now in. Moreover, we’ve designed the system to do much of this work automatically. As income falls and unemployment rises, we have an automatic system of progressive taxation and relief, which generates large budget deficits and rising deficits. Hooray! This is precisely what puts dollars in the pockets of households and private businesses, and stabilizes the economy. Then, when the private economy recovers, the same mechanisms go to work in the opposite direction.

For this reason, a sharp rise in the ratio of debt to GDP, reflecting the strong fiscal response to the crisis, was necessary, desirable, and a good thing. It is not a hidden evil. It is not a secret shame, or even an embarrassment. It does not need to be reversed in the near or even the medium term. If and as the private economy recovers, the ratio will begin again to drift down. And if the private economy does not recover, we will have much bigger problems to worry about, than the debt-to-GDP ratio.

It is therefore a big mistake to argue that the next thing the administration and Congress should do, is focus on stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio or bringing it back to some “desired” value. Instead, the ratio should go to whatever value is consistent with a policy of economic recovery and a return to high employment. The primary test of the policy is not what happens to the debt ratio, but what happens to the economy.

*****

Now, what about those frightening budget projections? My friend Bob Reischauer has a scary scenario, in which a very high public-debt-to-GDP ratio leaves the US vulnerable to “pressure from foreign creditors” – a euphemism, one presumes, for the very scary Chinese. Under that pressure, interest rates rise, and interest payments crowd out other spending, forcing draconian cuts down the line. To avert this, Bob has persuaded himself that social spending cuts are required now, not less draconian but implemented gradually. Thus the frog should be cooked bit by bit, to avoid an unpleasant scene later on when the water is really boiling hot.

With due respect, Bob’s argument displays a very vague view of monetary operations and the determination of interest rates. The reality is in front of our noses: Ben Bernanke sets whatever short term interest rate he likes. And Treasury can and does issue whatever short-term securities it likes at a rate pretty close to Bernanke’s fed funds rate. If the Treasury doesn’t like the long term rate, it doesn’t need to issue long-term securities: it can always fund itself at very close to whatever short rate Ben Bernanke chooses to set.

The Chinese can do nothing about this. If they choose not to renew their T-bills as they mature, what does the Federal Reserve do? It debits the securities account, and credits the reserve account! This is like moving funds from a savings account to a checking account. Pretty soon, a Beijing bureaucrat will have to answer why he isn’t earning the tiny bit of extra interest available on the T-bills. End of story.

The only thing the scary foreign creditors can do, if they really do not like the returns available from the US, is sell their dollar assets for some other currency. This will cause a decline in the dollar, some rise in US inflation, and an improvement in our exports. (It will also cause shrieks of pain from European exporters, who will urge their central bank to buy the dollars that the foreigners choose to sell.) The rise in inflation will bring up nominal GDP relative to the debt, and lower the debt-to-GDP ratio. Thus, the crowding-out scenario Bob sketches will not occur.

I’m not particularly in favor of this outcome. But unlike Bob Reischauer’s scenario, this one could possibly occur. If it did, it would lower real living standards across the board. This is unpleasant, but it would be much fairer than focusing preemptive cuts on the low-income and vulnerable elderly, as those who keep talking about Social Security and Medicare would do.

****

Now, it is true, of course, that you can run a model in which some part of the budget – say, health care – is projected to grow more rapidly than GDP for, say, 50 years, thus blowing itself up to some fantastic proportion of total income and blowing the public finances to smithereens. But this ignores Stein’s Law, which states that when a trend cannot continue it will stop, and Galbraith’s Corollary, which states that when something is impossible, it will not happen.

Why can’t health care rise to 50 percent of GDP? Because, obviously, such a cost inflation would show up in – the inflation statistics! – which are part of GDP. So the assumption of gross, uncontrolled inflation in health care costs contradicts the assumption of stable nominal GDP growth. Again, the consequence of uncontrolled inflation is… inflation! And this increases GDP relative to the debt, so that the ratio of debt to GDP does not, in fact, explode as predicted.

I do not know why the CBO and OMB continue to issue blatantly inconsistent forecasts, but someone should ask them.

Further confusion in this area stems from treating Social Security alongside Medicare as part of some common “entitlement problem.” In reality, health care costs and haphazard health insurance coverage are genuine problems, and should be dealt with. Social Security is just a transfer program. It merely rearranges income. For this reason it cannot be inflationary; the only issue posed is whether the elderly population as a whole deserves to kept out of poverty, or not.

Paying the expenses of the elderly through a public insurance program has the enormous advantage of spreading the burden over all other citizens, whether they have living parents or not, and of ensuring that all the elderly are covered, whether they have living children or not. A public system is also low-cost and efficient, and this too is a big advantage. Apart from that, whether the identical revenue streams are passed through public or private budgets obviously has no implications whatever for the fiscal sustainability of the country as a whole.

****

What is politically sustainable is nothing more than what the political community agrees to at any given time. I have been surprised, and pleased, by the political community’s acquiescence in the working of the automatic stabilizers and expansion program so far. The deficits are bigger, and therefore more effective, than many economists thought would be tolerated. That’s a good sign. But it would be a tragedy if alarmist arguments now prevailed, grossly undermining job prospects for millions of the unemployed.

Let me note, in passing, that Chairman Bernanke should please read the Federal Reserve Act, and focus on the objectives actually specified in it, including “maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.” He does not have a remit to add stable debt-to-GDP ratios or other transient academic ideas to the list. One might think that the embarrassing experience with inflation targeting would be enough to warn the Chairman against bringing too much of his academic baggage to the day job. “