By Matthew Berg*

Introduction

This paper argues that a monetary production credit economy must necessarily have a hierarchy of money (Foley 1983; Bell 2001) in which some IOUs are more liquid and more acceptable than others, and in which default on IOUs is possible. The imposition of a tax liability by the government is a sufficient condition not only to ensure that the government’s IOU is acceptable (Wray 2012), but also to ensure that at least some non-government IOUs will be acceptable to the degree that they can be converted into government IOUs – that is, to the degree that they are liquid.

Banks are institutions which exchange their own IOUs for the IOUs of borrowers who stand lower in the hierarchy of money than banks. Borrowers take out loans from banks for the purpose of buying goods, services, or financial asset from a third party. Banks (and central banks) act as the “ephors” of capitalism – and as the ephors of the hierarchy of money – by deciding which IOUs shall be “validated” and effectively converted into government IOUs, and by deciding when and for how long those IOUs shall be validated.

In a monetary production economy, the aim of production is to obtain money. Money is abstract wealth which the money-holder can convert into real wealth at an undefined time and place of the money-holder’s choosing. In order to preserve the existence of a monetary production economy, banks must necessarily preserve the hierarchy of money by sometimes refusing to validate at least some IOUs. That is to say, banks must engage in underwriting, default must be possible, and IOUs must be unequally acceptable in order for money to remain as abstract wealth. Only if money remains abstract wealth will real goods and services be produced and sold for money – thus only if banks engage in underwriting can a monetary production economy be maintained.

Assuming one wishes to maintain a monetary production economy, the policy implications of this are fairly straightforward: first and foremost, banks must engage in underwriting, which in practice means they must hold the loans they make on their own balance sheets. But this is not enough by itself; if central banks do not engage in “underwriting” of banks by letting at least some banks fail at least some of the time, then banks will have no incentive to engage in underwriting even if they keep their own loans on their own balance sheets. Banks should be allowed (and perhaps encouraged) to act as “ephors” in ways which are consistent with the public purpose, and not in ways which are inconsistent with the public purpose. This means that banks should make loans that support the capital development of the economy, and should not make loans that do not support the capital development of the economy. However, if promoting the capital development of the economy is deemed a desirable policy goal, it should be pursued through all available means, and not simply through encouraging private banks to make loans. Finance is not a scarce resource, and can be provided at will by sovereign governments to promote the public purpose. In some or even many cases, the capital development of the economy may be better achieved either through direct lending by the government, or alternatively not by lending at all – but by government spending, which creates private sector income and net financial wealth.

An Economy with no Banks

In order to understand what banking is, a good point of departure is to briefly consider what the world might be like if there were no banks – a revised version of Schumpeter’s circular flow (1961). Without banks – or shadow banks, including any person’s ability to issue their own IOU – the only source of money in the economy would stem from government deficit spending. When, because of leakages (such as taxes, imports, or attempted savings) from the circular flow, insufficient aggregate demand led to unemployment, the unemployment would lead to increased government budget deficits. The increased government budget deficits would cause the stock of outstanding government debt to increase, up until the point at which increased consumption out of wealth caused at least some of the unemployment to disappear and eliminated the government’s budget deficit. The increased spending out of the larger stock of private sector wealth also has a multiplier effect, which to some degree also increases income and therefore spending out of not just wealth, but also out of income. This is the result, for instance, of simple Stock-Flow Consistent models such as Godley’s and Lavoie’s “SIM” model (2007, p. 57–78).

In reality, there are several reasons why the stock of government debt never approaches such a simple “steady state” quantity. First, the economy is dynamic and the private sector’s desire to net save, is always changing, which prevents long period “steady state” positions from actually ever being reached. Secondly, the fact that both the population and the economy are growing means that, in general, the “steady state” stock of government debt must grow at the same rate. Thirdly, inflation, which is usually positive, has an impact. Inflation reduces the real value of the government debt stock, which is an asset of the private sector. For instance, suppose inflation is 2% per year. If the private sector is to maintain a given stock of real wealth (the “SIM” model assumes this to be the case), the government debt stock must grow by an additional 2% per year in order to offset the effect of inflation.

The existence of banks, therefore, disrupts an endogenous process through which, over time, the stock of government debt adjusts to meet private sector desires for net financial assets, with a quantity adjustment of unemployment acting as the principal adjustment mechanism. By making loans, banks expand their balance sheets on both the asset side and the liability side, thereby creating new purchasing power which can potentially fill any extant demand gap.

This disruptive effect of banks can have both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, by creating an additional potential adjustment mechanism besides unemployment, the existence of banks can help to decrease unemployment in the short run, since bank loans are a potential source of aggregate demand. A second positive effect, emphasized by Schumpeter, is that banks make possible the creation of purchasing power for entrepreneurs who do not have current income flows, but who would spend purchasing power in a way which would generate future income flows – through innovations that contribute to the capital development of the economy.

But one drawback is that banks could potentially make too many loans, or may make loans to firms which are competing over bottlenecked inputs, and this additional spending power could result in inflation. A second potential drawback is that banks can make loans which do not finance the capital development of the economy, but instead are used to purchase financial assets, which only serves to increase financial leverage ratios and thereby increases the economy’s tendency to financial instability.

Direct Credit Expansion Without Banks

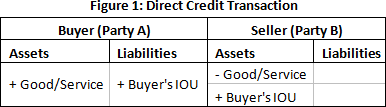

Suppose that a buyer (Party A) wishes to purchase a good or service from a seller (Party B), but has no cash with which to pay the seller. Party B likewise wishes to sell its good or service to Party A, but needs to receive something in payment, which the Party A does not have. This transaction could take place, without any involvement whatsoever by banks, if the Party B were to simply accept Party A’s IOU directly, in lieu of monetary payment. In this case, as shown in Figure 1, Party A expands its balance sheet on both sides, acquiring a good or service and “paying for it” by issuing an IOU. Party B, in turn, acquires Party A’s IOU in exchange for the good or service. If the value of the good or service equals the value of the Party A’s IOU, then the transaction nets out to zero for both the buyer and the seller.

At this point, Party B has acquired something of real value – the good or service provided by Party A. But Party B possesses something of an altogether different character – Party A’s IOU. That is to say, Party A’s IOU, which is Party A’s liability, is now Party B’s asset. But what is the Party B to do with Party A’s IOU? One possibility is that Party B could simply hold it forever. In this case, the Party B has essentially performed an act of charity for the Party A: the Party B has provided the Party A with a good or service, with no expectation of ever obtaining any sort of real good or service in return.

If Party B is not to hold Party A’s IOU forever, there are two possible ways Party B can dispose of it (besides simply swapping the IOU for another Party’s IOU). The first option is that roles could reverse and the former seller (Party B) could buy a good or service from the former buyer (Party A). A second option is that Party B could buy a service from someone else altogether (Party C), apart from Party A. But in either of these latter two cases, the question arises of how Party B will “pay for” its purchase of the good or service. And in both cases, there are two ways in which Party B could potentially “pay for” its purchases – by either using Party A’s IOU, or by issuing its own IOU. In the case where Party B uses Party A’s own IOU to purchase a good or service from Party A, Party A has accepted its own IOU back as payment, which means it ends up with its own IOU as both a liability and an asset. In this case, the asset and the liability cancel out, and Party A’s IOU is extinguished. In the case that Party B purchases from Party C, using Party A’s IOU as a means of payment, Party A’s IOU is simply transferred from Party B to Party C. In the case that Party B purchases from either Party A or from Party C by issuing its own IOU (Party B’s IOU), then credit expands analogously to the case shown in Figure 1.

The Relationship Between Banks, Default, Liquidity, and the Hierarchy of Money

If all parties were always willing to accept all other parties’ IOUs, then the sort of credit expansion illustrated in Figure 1 could go on forever – without any involvement whatsoever by banks. In fact, if all IOUs are always acceptable to everyone, then the possibility of default is ruled out, since a debtor can always make current payments by issuing an additional IOU (which is always acceptable, by assumption). This illustrates Goodhart’s point that without the possibility of default, there is no reason for banks to exist (2008).

But this is not the world in which we live, and banks cannot be so easily eliminated from a monetary production economy. In order to understand why this is the case, we must integrate the above understanding of the capacity of any entity with a balance sheet to create to endogenously create credit with an understanding of the hierarchy of money, and must understand the close and important connection between banks, default, and the hierarchy of money. If everyone’s IOUs were always acceptable to everyone else, as in the case of direct credit expansion with a non-hierarchical money, then no-one would ever have any incentive to produce real goods or services and then to exchange those goods or services for money. Everyone’s own IOUs would all already be the best “money” available, so everyone would simply attempt to buy the goods and services they wanted by simply issuing their own IOUs. But with no real goods or services available in exchange for money, money would become worthless as an instrument with which to acquire real goods and services, and hence would no longer function as a unit of measurement for the value of real goods and services. For this reason, the very notion of a capitalist monetary economy requires that there be a hierarchy of money, in which not all IOUs are equally acceptable, and requires that there be a possibility of default. We therefore must examine a world with both banks and a hierarchy of money.

To explain this from a slightly different vantage point, consider Clower’s (1965) argument that “money buys goods and goods buy money, but goods do not buy goods.” This rules out barter and makes the observation that the aim of production in a monetary production economy is to acquire money, which may be thought of as wealth in abstract form (Levine 1983). People want to acquire money for its own sake – not to buy any particular good or service at any particular time (and not necessarily to ever buy a good or service). But the fact that the aim of production in a monetary production economy of the sort described by Keynes (1973, pp. 408-11) is the acquisition of money this says nothing about why producers wish to acquire money.

The fact that people specifically want money – a very specific IOU, and not just any IOU – indicates that something more is going on, and that there is a (subtle and indirect) connection between the desire to acquire money and the desire to acquire real goods and services. If producers simply wanted IOUs for the sake of having IOUs, then clearly any IOU would do. But not any IOUs will do – what is wanted are liquid IOUs, especially the IOU which ranks highest in the hierarchy of money, which in practice is the government’s IOU. People do not want money simply because it is an IOU, but rather because it is wealth in abstract form. If something is wealth in abstract form, then it must be convertible into wealth in real form (that is, into real goods and services).

Money is an option to acquire real goods and services at an indefinite future time and place of one’s choosing. The possession of money provides power and security in an uncertain world: a buffer stock of wealth that can be run down, allowing people and firms to maintain lifestyles and business strategies (respectively) when expectations are disappointed. People may also wish to acquire other IOUs (other financial assets) as well as money. But they only wish to acquire those other IOUs to the extent that those other IOUs can be (or can be expected in the future to be) converted into money, and hence the extent to which those IOUs also serve as indirect options to acquire real goods and services at an indefinite future time and place of one’s choosing. The extent to which this is the case is the degree to which an IOU is liquid, and “liquidity” is simply another word for the position occupied by a financial asset in the hierarchy of money. To re-emphasize, in order for money to have value, the holder need never actually convert money into a real good or service. But the holder must always have the option of so doing.

The Necessarily Hierarchical Nature of Money

To understand why there must be a hierarchy of money, Let us consider the logical consequences of a world with no hierarchy of money. With no hierarchy of money, all IOUs would by definition be perfect substitutes. And if all other IOUs were perfect substitutes for government IOUs, then it follows that those other IOUs would be equally good vessels of wealth in abstract form as are government IOUs; they would be just as good options to acquire real goods and services as government IOUs.

But this presents a problem: IOUs are not a scarce resource, and an infinite number of IOUs could potentially be created. But at any particular point in time, the quantity of real goods and services which are available are finite. If all IOUs were perfect substitutes, then all IOUs would always be equally acceptable; anyone could always pay for any real good or service simply by issuing their own IOU. Moreover, anyone could always pay any interest on any debts simply by issuing more of their own IOUs, which by assumption are always equally acceptable to all other IOUs.[1] Therefore, in order to have the option of acquiring real goods and services, it would never be necessary to acquire government IOUs; since nobody can ever run out of their own IOUs, everyone would effectively always have an infinite amount of their own IOUs, which would be equivalent to having an infinite amount of government IOUs.

Since the aim of production in a monetary production economy is to acquire government IOUs, and since we have also deduced that in a world with no hierarchy of money everyone would always effectively have the equivalent of an infinite amount of government IOUs, it follows that nobody would ever need to produce goods and services to acquire government IOUs. Of course, people would still produce goods and services (indeed, they would need to in order to survive), but the point is that they would never sell goods and services; there would be a production economy, but there would no longer be a monetary production economy. With no goods or services for sale, the value of all IOUs in terms of real goods and services would drop to zero.

Money, as Keynes said in Chapter 17 of the General Theory, “cannot be readily produced.” Or, as Paul Davidson has often put it, money does not (and necessarily cannot) grow on trees. If it did, we would simply reach up and pick the money off the trees, any time we wanted money – which would mean that money would be worthless – and therefore would no longer be money. A world without a hierarchy of money would be precisely a world in which money “grew on trees,” because anyone could create money simply by issuing their own IOU – simply by “picking it” out of thin air. And so it is clear that money cannot be entirely free and unconstrained. But for a well-functioning financial system to exist, money must also not be arbitrarily fixed at a certain quantity. Money is predestined to inhabit a slippery crepuscular between-world – ordained to be neither completely free nor entirely constrained, and condemned to incarceration at the hand of its own perilous freedom.

We have therefore deduced that a necessary condition for the existence of a monetary production credit economy is the hierarchy of money: if there is not a hierarchy of money, then the value of money falls to zero and all monetary production ceases. In a monetary production economy, it must be the case that some IOUs are more liquid and acceptable than others, and it must also be the case that default sometimes occurs.

As we have established, the value of all IOUs in a world with no hierarchy of money would fall to zero. However, a sufficient condition for the government (or some other entity) to establish a positive value for its IOUs is the imposition of a tax obligation (or other obligation) that is dischargeable only in the government’s (or the entity’s) own IOU. But in imposing a tax liability, the government does not merely raise the value of its own IOU above zero. As long as it is possible (not legally prohibited) for entities other than the government to issue IOUs, and as long as it is possible for at least some of those IOUs to be converted into government IOUs, the imposition of a tax liability by the government also necessarily raises the value of at least some other IOUs above zero. The imposition of a tax liability establishes a hierarchy of money, in which some IOUs are worth more than others, depending upon how readily they can be converted into the government’s IOUs. And for the maintenance of the hierarchy of money, it must necessarily be the case that default sometimes occurs (or can conceivably occur) on at least some of the IOUs that stand below the state’s IOUs in the hierarchy of money.

Moreover, if all IOUs were always equally acceptable, then anyone could also pay any nominal tax obligation simply by issuing their own IOUs and exchanging them for (equally acceptable) government IOUs. An alternative way to think about this is that if all IOUs were always equally acceptable, that would imply that they were always equally all IOUs were always acceptable to all parties – including to the government. This is to say that the equal acceptability of all IOUs would be contradicted by the imposition of a tax liability payable only by returning the government’s own IOU to the government. It is therefore easy to see why the imposition of just such a liability – payable only in terms of the government’s IOU – necessarily creates at least some hierarchy in the monetary system, rendering the equality of all IOUs impossible. This is not strictly unique to the government – any entity can contribute to maintaining the hierarchy of money simply by setting conditions and limitations upon which IOUs it will accept in payment.

The fact that some IOUs stand lower in the hierarchy of money than other IOUs means that parties that stand lower in the hierarchy of money cannot always transfer real resources from the rest of society to themselves simply by issuing their own IOUs. Instead, at some point entities lower in the hierarchy of money must are forced to stop acquiring real resources by issuing IOUs, and are instead forced to produce real goods and services in order to obtain higher-ranking IOUs. When a bank accepts the IOU of a lower-ranking entity in the hierarchy of money, it does so because it believes that in so doing it can increase its own quantity of abstract wealth (options to purchase real goods and services). By accepting the IOU, the bank takes on the risk that the lower-ranking entity will default, but the bank believes that the interest it charges on its aggregate loans made will exceed losses from aggregate defaults.

Liquidity Risk and Solvency Risk

The hierarchy of money in a monetary production economy is necessarily characterized by two distinct types of risk: liquidity risk and solvency risk. The nature of these risks must be understood in order to understand what banks do, and how the essential function of banking (underwriting) necessarily arises from the hierarchy of money. The concepts of liquidity risk and solvency risk can be applied to all entities with balance sheets, but for purposes of exposition we will refer to “banks.”

Liquidity risk is the risk that a bank’s future cash flows may not be aligned in time so as to make it possible for the bank to meet its past payment commitments, including the risk that the bank might not be able to roll-over such past commitments and extend the date of settlement further into the future by taking out a new loan. Solvency risk is the risk that, due to losses on assets, a bank’s liabilities may exceed its assets, which means the bank would have a negative net worth and therefore would be insolvent.

Liquidity risk and solvency risk are conceptually distinct, and must be considered differently for policy purposes, if a well-functioning financial system is to be maintained. But despite this conceptual distinctness, illiquidity and insolvency are interrelated in the practical sense that – if left unchecked by policy, both insolvency can lead to illiquidity and illiquidity can lead to insolvency. Solvency problems can lead to liquidity problems because if a bank is suspected of being insolvent, other banks may be hesitant to lend to it. This means that other parties will not accept the (suspected) insolvent bank’s IOUs, which is the definition of illiquidity. Liquidity problems can also lead to solvency problems because in a credit crunch, an illiquid bank may have to pay higher interest rates to roll over its past commitments, and these higher than expected interest payments may deplete the bank’s net worth, and eventually drive it into insolvency.

Credit Expansion with Banks

In a world with a hierarchy of money, institutions must exist which allow for IOUs on different levels of the hierarchy of money to be exchanged in a controlled and regular way. Those institutions are banks. Banks most certainly do not function as intermediaries in the sense of equilibrating saving and investment, or in the sense of “lending out” deposits or a scarce quantity of “loanable funds.” However, banks do serve as “intermediaries” in a very different sense, by placing its balance sheet between two parties that wish to transact with one another, but which otherwise could not transact without the bank’s involvement.

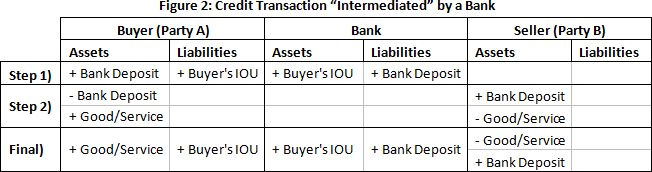

The case of a credit transaction “intermediated” by a bank is shown in Figure 2 below. For purposes of exposition, the process of a credit transaction is broken into two steps, but in fact these two steps occur simultaneously. In Step 1, the bank begins by making a loan to a borrower (Party A). The bank makes the loan by expanding its balance sheet on both sides, accepting Party A’s IOU as the bank’s asset and making a bank deposit available to Party A as a liability of the bank. At the same time, Party A also expands its balance sheet on both sides, issuing its own IOU as a liability to the bank and accepting the bank’s bank deposit in return. This is a swap of IOUs between Party A and the bank, but it is not a swap among equals; it is a swap across different levels of the hierarchy of money. It is necessarily the case that the bank’s IOU is more acceptable and more liquid than Party A’s IOU, or else the transaction would either not take place, or else it would in fact be Party A – not the “bank” – that was in fact acting as a bank. In Step 2, a seller (Party B), which has done work of some sort to acquire a real good or service, exchanges that good and service with a buyer (Party A) in exchange for the bank’s IOU, which had become Party A’s asset in Step 1. Hence, Party B loses a real asset and gains a financial asset. At the same time, the buyer (Party A) loses a financial asset (the bank deposit) and gains a real asset (the good or service). In contrast to Step 1, neither party involved in Step 2 (neither Party A nor Party B) expands its balance sheet on both sides. Step 2 is not a swap of IOUs, but rather is an exchange of a real asset for an IOU (a financial asset).

But as mentioned, in reality Step 1 and Step 2 occur simultaneously, for a simple reason. The bank does not trust that Party A will actually use the bank deposit to buy the real asset from Party B, (which was the reason why the bank agreed to make a loan to Party A in the first place). The bank wants to avoid the possibility that Party A might simply withdraw the bank deposit and abscond (assuming a clearing and withdrawal mechanism is set up). Therefore the bank directly makes the payment to Party B on behalf of Party A, but for the purpose of protecting the bank. For Party A, the “+ Bank Deposit” asset entry and the “- Bank Deposit” asset entry cancel out when Step 1 and Step 2 are combined and occur simultaneously, yielding the final result shown in Figure 2.

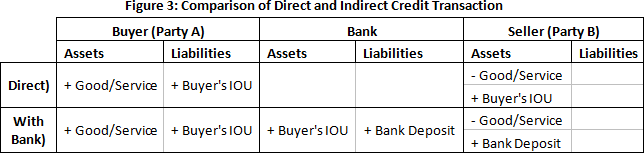

For ease of comparison, the final result of a direct credit expansion and an indirect credit expansion involving a bank are shown together in Figure 3, one on top of the other.

Interestingly, the buyer (Party A) has the same balance sheet structure regardless of whether or not a bank is involved in the transaction. In both cases, Party A ultimately obtains a real good or service as an asset, and “pays for it” by issuing its own IOU. But a concrete difference between the two cases shows up in the balance sheets of the seller, (Party B). In the case of direct credit expansion, Party B ends up with Party A’s IOU as an asset, whereas in the case of credit expansion with a bank, Party B ends up with a bank deposit (the bank’s IOU) as an asset. In both cases Party B loses the real good or service, which is transferred to Party A.

The logical implications of this balance sheet analysis are somewhat surprising and at least initially may be counterintuitive. What the involvement of the bank in the transaction principally accomplishes, in comparison to the case of a direct credit transaction, is to substitute the bank’s IOU for Party A’s IOU on the balance sheet of Party B. When a bank makes a loan, the primary service the bank provides is not to the customer that takes out the loan, but rather is to the third party from which the borrower purchases. On the bank’s balance sheet, it takes Party A’s IOU (lower on the hierarchy of money) as an asset and simultaneously issues the bank’s IOU (higher on the hierarchy of money) as a liability. The bank is essentially “endorsing” or “validating” Party A’s IOU as a service to Party B, so that Party B can obtain a sufficiently liquid asset, which is sufficiently high in the hierarchy of money to be acceptable as a means of payment. The endorsement of the borrower’s IOU, and the concomitant effective transformation of the borrower’s IOU – via the bank’s balance sheet – into the bank’s own IOU, is the central function of banking. The “mediation” of the bank “has the advantage to the seller of establishing the presumption that the buyer did deliver something of value at some time to the third party or to another party” (Foley 1983, p. 11).

Moreover, since government policy in modern developed nations is that bank IOUs should trade at par with government IOUs, banks enable third parties to receive payment denominated not just in the form of the bank’s IOU, but also in the form of the government’s IOU. Effectively, by approving a loan, a bank enables the borrower’s IOU to count at par with the government’s IOU. Banks effectively collapse (to a limited extent) the hierarchy of money, granting liquid purchasing power to borrowers for the benefit of sellers who demand payment in liquid government IOUs, as opposed to in the illiquid IOUs of their customers.

Banks as Public-Private Partners

While commercial banks are merely legal institutions, the essential core of banking – credit creation – is much more fundamental and cannot be easily abolished by legal decree. As Minsky put it, “everyone can create money; the problem is to get it accepted” (2008, p. 255) Innes (1913; 1914) recognized the same point many years earlier. As we have examined above, anyone can create credit by simply issuing their own IOU, thereby simultaneously expanding their balance sheets on both sides. What makes banks special is not their ability to simultaneously create loans and deposits, but rather is the fact that their IOUs are more acceptable than their customers’ IOUs, which is to say that banks stand a step above their customers in the hierarchy of money.

Prior to the advent of the Federal Reserve, bank IOUs were somewhat more acceptable than many other IOUs for the same reasons that a large corporation’s IOUs are currently more acceptable than an individual person’s IOUs: largely because of social convention and because of the fact that they were established institutions. However, the degree of higher acceptability of bank’s IOUs in this period was severely constrained by problems such as the lack of par clearing and the ever-present risk of bank failure.

But in the modern era, banks’ position in the hierarchy of money is more firmly rooted by pre-arranged and institutionalized government backing. Banks have access to the payments system, through which the Federal Reserve ensures par clearing. Banks can convert their own IOUs into the Federal Reserve’s IOUs at will by depositing their own IOUs at the fed. Depositors are protected from the risk of bank insolvency by FDIC deposit guarantees, and banks are protected from liquidity risk through their access to the Federal Reserve’s lender of last resort facilities. Because of this multifaceted government involvement in banking, modern banks must be considered as public-private partners, rather than purely private companies.

Implications for Policy

Assuming that one wishes to maintain a monetary production economy, the policy implications of this understanding of banking are fairly straightforward: first and foremost, banks must engage in some form of underwriting in order to preserve the hierarchy of money and prevent ponzi finance from becoming infinitely sustainable. However, while banks must conduct some sort of underwriting, this does not specify precisely what sort of underwriting banks should conduct. Private banks, unless they are given government subsidies, can only survive if they make a profit. Therefore they will only make loans when expected interest payments exceed expected losses from defaults and the other costs of doing business. So that banks will have an incentive to make loans which will not be defaulted on, banks must be required to hold their own loans on their own balance sheets. Further, banks should be allowed (and perhaps encouraged) to act as “ephors” in ways which are consistent with the public purpose, and not in ways which are inconsistent with the public purpose. This means that banks should make loans that support the capital development of the economy, and should not make loans that do not support the capital development of the economy.

But it is not necessarily true that all profitable loans are in the public interest, nor is it necessarily the case that only loans which are expected to be profitable are in the public interest. Banks make some loans which are used to finance consumption, which can be profitable if made to creditworthy borrowers. However, it is not necessarily clear why it is a better use of limited present real resources to allow some people to consume momentarily beyond their income, as opposed to increasing incomes of the public at large through government spending or tax credits. Banks also make some loans to finance the purchase of other financial assets, as in the case of stock margin loans. These loans can be profitable, but there is no real reason to believe that financial speculation is in the public interest (and much reason to believe that it runs counter to the public interest). Other types of loans, such as student loans or some mortgage loans may have high default rates that make them unprofitable, but may nonetheless be deemed to be in the public interest. However, policy goals such as promoting education and home ownership can also be promoted more directly, by direct targeted government spending on grants, or more general increases in government spending to increase incomes so that people can afford to finance education and homes more out of income than out of debt. A common argument for promoting finance of capital development via “private” banks is that government spending would “crowd out” private spending, or that the government does not have enough money, but this is mistaken. The government is not (involuntarily) constrained in its ability to create its own IOUs. An expansion based on government spending also has the advantage of being extremely likely to result in greater financial stability than an expansion based upon the expansion of private debt. Moreover, the degree to which banks (and bank loans to entrepreneurs) really are responsible for innovation should not be exaggerated. Much innovation results from large enterprises’ internally financed research and development operations, as well as from government funding of basic research.

While the preservation of the hierarchy of money requires that banks engage in underwriting, it is not enough that only banks engage in underwriting. In order for banks to have an incentive to engage in underwriting, the central bank must also engage in its own variety of “underwriting.” If central banks do not engage in “underwriting” of banks by letting at least some banks fail at least some of the time, then banks will have no incentive to engage in underwriting even if they keep their own loans on their own balance sheets. If banks are the ephors of capitalism, then the central bank is the ephor of ephors.

The more comprehensive is the government guarantee of M-M’ transactions gone wrong, the greater the number of M-M’ transactions will tend to be attempted in the future, the greater and the greater the share of overall the economy will tend to fall into the grasp of the financial sector. Financialization of the economy is a consequence of a secular decline in underwriting by banks and of a secular increase in the willingness of central banks and governments to provide liquidity and bailouts on demand in times of financial crisis. Taken to its extreme logical conclusion, the ultimate consequence of a continued secular trend of financialization is the equality of all IOUs, a breakdown in the hierarchy of money, a cessation of all production of real goods and services sold for money, and a collapse of the value of all IOUs to zero. This is a transformation of a monetary production economy to a monetary financial economy. Since comprehensive financialization renders monetized production impossible, this is ultimately the same thing as the transformation of a monetary production economy to a non-monetary production economy.

Conclusion

I have argued that a monetary production credit economy must necessarily have a hierarchy of money. The imposition of a tax liability by the government is a sufficient condition not only to ensure that the government’s IOU is acceptable, but also to establish a hierarchy of money. The function of banks is to transcend the hierarchy of money, validating low-ranking IOUs by converting the low-ranking IOUs of borrowers into higher-ranking IOUs. Banks use their balance sheets to do this, and take on liquidity risk and solvency risk in the process of conversion. In this capacity, banks act as the overseers (“ephors”) of capitalism and of the hierarchy of money by deciding which IOUs to validate. In order to accomplish this, banks must refrain from simply accepting all loan applications, and must use underwriting to reject at least some loan applications. The capital development of the economy can be promoted by policies that ensure that banks engage in underwriting. In addition, the capital development of the economy can be promoted through other means, such as fiscal policy.

[1] We may note that this is the same thing as saying that Ponzi finance would be infinitely sustainable, and also implies that there would never be any default.

*A Note:

For the next few weeks we will be running a series of articles on monetary theory and policy. These are final essays written by MA students in my class this past Fall semester. I was very happy with the results—students indicated that they had a firm grasp of both the orthodox approach as well as the heterodox approach to the subject. Most of them also included some Modern Money Theory in their answers. I asked about half of the students in the class if they would like to contribute their essay to this series. Sometimes students are the best teachers because they see things with a fresh eye and cut to what is important. They are usually less concerned with esoteric academic debates than are their professors. Note that these contributions are voluntary and are written by Masters students. I told students they could choose to use their own names, or they could choose an alias. Comments are welcome, but please be nice—remember these are students.

For your reference, here were the topics for the paper. The paper had a maximum limit of 6000 words.

Choose one of the following. You must consider and address both the orthodox approach and the heterodox approach in your essay. Where relevant, include various strands of each.

A) What is the nature of money? Given the nature of money, what approach should be taken to policy-making?

B) What is the nature of banking? Given the nature of banking, what approach should be taken to policy-making?

C) According to John Smithin there are several main themes throughout controversies of monetary economics, each typically addressed by each of the various approaches to monetary theory and policy. In your essay, discuss how each of the approaches we covered this semester tackles these themes enumerated by Smithin.

L. Randall Wray

References:

Bell, Stephanie. 2001. “The role of the state and the hierarchy of money”. Cambridge Journal of Economics 25(2): 149–163.

Clower, Robert. 1965. “The Keynesian Counter-R evolution: A Theoretical Appraisal.” in F.H. Hahn and F.P.R. Brechling (eds.), The Theory of Interest Rates. London: Macmillan.

Foley, Duncan K. (1983). “On Marx’s Theory of Money,” Social Concept 1(1), 5-19.

Godley, W and Lavoie, M. (2007). Monetary Economics: An Integrated Approach to Credit, Money, Income, Production and Wealth, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Goodhart, Charles A.E. (2008). “Money and Default.” in Mathew Forstater and L. Randall Wray (eds.), Keynes for the Twenty-First Century: The continuing relevance of the General Theory. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Innes, Mitchell A. (1913). “What is Money?,” Banking Law Journal 30.5: 377–408.

Innes, Mitchell A. (1914). “The Credit Theory of Money,” Banking Law Journal 31.2: 151–168.

Keynes, John Maynard. (1973). The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol 13. ed. by Donald Moggridge. The General Theory and After, Part I. London and Basingstoke: The MacMillan Press, Ltd.

Levine, David. (1983). “Two Options for the Theory of Money.” Social Concept, 1(1), May: 20-29.

Minsky, Hyman P. (2008). Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1961). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wray, L.R. (2012) Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems. New York: Palgrave.

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: On the Na...

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: on the Nature of Money Pt. 2 - EXPOSING BLACK TRUTH