By Ryan M. Pope*

Hyman P. Minsky said he thought there were as many forms of capitalism as Heinz had pickles. The same can be said about the different types of banking within the financial system. The system has undergone a dramatic transformation over the development of the capitalist economy, and Minsky spent a large amount of time studying this transformation. Many economists feel the same way as Minsky did, that the results achieved by a capitalist economy can be viewed from two fundamentally different perspectives: the Smithian way and the Keynes way. The Smithian way assumes the presence of an “invisible hand”, and therefore “intervention or regulation can only do mischief.” (Minsky 1991, 5) In contrast, the Keynes way assumes that the economy is naturally unstable, and “… regulation and intervention can be beneficial.” (Minsky 1991, 5) When designing economic policies, government leaders must choose between these two perspectives. This is exactly what policy makers have done over the evolution of the capitalist economy, and their decisions have transformed the banking system in many ways.

What follows is an analysis of the evolution and nature of banking through Minsky’s four distinct stages of capitalism – “commercial”, “industrial”, “paternalistic”, and “money-manager.” We will begin by analyzing the capitalist economy and banking system from the orthodox perspective and the influence it has had on policymaking decisions. Minsky’s perspective will then be introduced, followed by an analysis of banking through his stages approach to capitalism. Finally, we will examine alternative policy prescriptions for the banking system based on the recommendations of Minsky and other scholars regarding what banks should do.

Contrasting Views of the Economy and its Participants

The orthodox model of a capitalist economy is possible only in a fictional, perfect world. The problem, however, is that many economists, business professionals, and policy makers were (and still are) subscribers to orthodox theory and the assumption that capitalist market economies contain a set of inherent characteristics. These characteristics are as follows: [i]

- all economic agents (households and firms) are rational and driven to maximize profits;

- all markets are perfectly competitive, with agents basing their decisions to buy or sell on a given set of perfectly flexible prices;

- prior to buying or selling in the market, all agents obtain perfect information regarding both prices and market conditions;

- buying and selling takes place only after a fictional Walrasian auctioneer establishes market-clearing prices; and

- rational agents have stable expectations.

The orthodox model, therefore, is assumed to be an inherently equilibrium seeking system with an “invisible hand” ensuring continuous market clearing. This translates to the belief that financial systems and markets function efficiently because both they and the systems’ participants possess perfect information regarding prices and market conditions.

This view has led to numerous periods in history in which laissez-faire government policy has dominated, leaving markets to be predominately self-regulated due to their assumed “inherent efficiency.” Indeed, the two most significant financial crises in U.S. history – the “Great Crash” of 1929 and the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 – were preceded by periods characterized by a “free market” approach to financial regulation. History shows us, however, “… that the natural laws of development of capitalist economies leads to the emergence of conditions conducive to financial instability.” (Minsky 1991, 5-6)

The general-equilibrium theory of orthodox economics is still influential in today’s economic environment. For example, Eugene Fama has recently received recognition[ii] for his “Efficient-Market Hypothesis”, a theory he began developing in the 1960s, which argues that the market prices of assets reflect all readily available information. The orthodox view of the capitalist economy, therefore, with its perfect information and efficient markets, assumes that banking and the overall financial system do not matter. Yet, as Minsky points out, “capitalism is a dynamic, evolving system that comes in many forms … [and] … nowhere is this dynamism more evident than in its financial structure.” (Minsky and Whalen 1996, 2-3) Hyman P. Minsky dedicated a large amount of time to analyzing the financial system of a capitalist economy and felt the strength of the financial system determines the strength of the overall capitalist economy.

Banking during Minsky’s Stages of Capitalism

In a paper written in April of 1992, Minsky takes a humorous approach to introducing the evolution of capitalism in America. “The Heinz Company, the well-known canner of pickles and purveyor of ketchup used to have a slogan 57 Varieties to describe the wide scope of products it offered. I used to say that there are as many varieties of capitalism as Heinz had of pickles …” (Minsky 1992, 37). Although slightly less than 57, Minsky identified four distinct stages of capitalism – “commercial”, “industrial”, “paternalistic”, and “money-manager” – and he notes “industrial” and “paternalistic” were the financial stages.

Commercial Capitalism

Commercial capitalism was a period in which firms financed production either internally, by reinvesting profits back into the firm, or by obtaining short-term loans from commercial banks. Minsky’s summary of banking in this stage of capitalism is much more concise, however:

Prior to the emergence of modern industrial capitalism, bank money was mainly created in financing commerce, namely, goods in the process of production and distribution. The label commercial banks reflects the original dominance of this type of financing in the business of banks. In such bank financing the near-term sale of goods furnished the cash needed to pay the bank debt. (Minsky 2008, 251)

As the nation expanded so did business, and expansion of the production process now required expensive, long-term capital assets. The cost of these capital assets required a level of financing commercial banks could not provide and it became necessary for firms to rely on external funds to expand production. This brought an end to Minsky’s “commercial” capitalism stage and marked the beginning of “industrial” capitalism.

Industrial Capitalism (With “Money-manager” on the Side)

WWI stimulates the U.S. economy and leads to a dramatic expansion from 1914-1918. American banks experience an increase in demand for new services as the European financial system is in turmoil, and Wall Street becomes the new center of the financial world. Following the war, the U.S. economy flourishes marking the beginning of a run of good times for the nation’s financial structure.

Three words are often associated with Minsky’s stages of capitalism and the evolution of the financial system: “stability is destabilizing.” This implies that a financial system “… evolves from being robust to being fragile over a period in which the economy does well.” (Minsky 1991, 16) The run of good times in the United States that began during WWI continued through the 1920s. Although Minsky still classified this period as the “industrial” capitalism stage, it would not be a stretch to consider it a preview of “money-manager” capitalism. Money-manager capitalism is a stage “… in which the proximate owners of a vast proportion of financial instruments are mutual and pension funds. The total return on the portfolio is the only criteria used for judging the performance of the managers of these funds, which translates into an emphasis upon the bottom line in the management of business organizations.” (Minsky 1996) I will cover this stage in detail a bit later in this essay; however, as we will see, “money-manager” capitalism is similar to the financial system present after WWI.

Throughout the 1920s, income and profits continued to exceed expectations, and households and firms responded accordingly by increasing indebtedness and decreasing their “margins of safety.” Households financed their consumption by increasing their liabilities, and the excessive leverage by firms constrained capital investment. As one writer of this era put it, a portion of the nation’s prosperity experienced during the 1920s “… undoubtedly rested on nothing more permanent than the process of credit expansion.” (Persons 1930, 101)

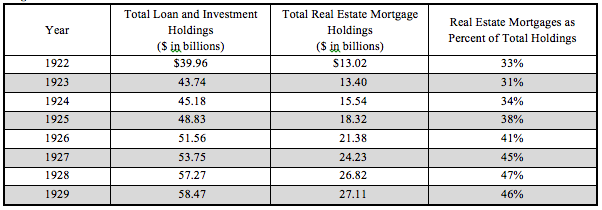

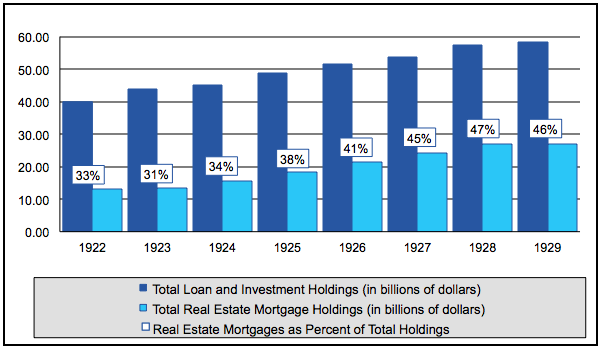

The early 1920s were a period in which U.S. banks increased lending, leverage, risk-taking, and diversification, a trend that continued for many years thereafter. Banks begin lowering their capital ratios by issuing mortgages and other long-term loans, and diversify their holdings issuing “… loans to stock market speculators on 90 percent margins.” (FDIC 2006) In a journal article published in November of 1930, Charles E. Persons documents the expansion of bank holdings in great detail.[iii] In June of 1922, loans and investments held by all member and non-member banks – which consists of national banks, state commercial banks and trust companies, mutual and stock savings banks, and all private banks under state supervision in the United States – totaled $39.96 billion. In June of 1929, that value totaled $58.47 billion – an increase of more than 46 percent in six years. (Persons 1930)

A substantial portion of this credit expansion by banks was in the form of real estate loans. As shown in the table and chart below, the total value of urban (non-farm residential) real estate holdings were $13.02 billion at the end of 1922, accounting for 32 percent of total bank credit extension. At the end of 1929, the combined value of all mortgages held by banks was $27.11 billion, just over 46 percent of total loan and investment holdings. The total real estate loans held by banks increased approximately 108 percent from 1922-1929.

Indeed, the expansion of credit by banks represented a significant increase in indebtedness for both the financial system and households – a very unstable position. As Persons explained it at the time, “we have undoubtedly greatly expanded the credit structure, spending today and postponing the accounting until tomorrow. We have been guilty of the sin of inflation. And there will be no condoning the sin nor reduction of the penalty because the inflation is of credit …” (Persons 1930, 104-105)

The financial system also saw the distinction between commercial banking and investment banking quickly erode as many banks created specialty units to handle their investment activities. For example, First National City Bank, and its investment subsidiary, the National City Company, employ 2,000 brokers selling stocks. (FDIC 2006) The speculative environment was also fueled by an increase in financial innovations that made it difficult to tell the difference between saving and investing. First National City Bank unveiled new financial instruments including compound-interest savings accounts and an investment fund called the “unit trust”. (FDIC 2006) As Wray explains, these “… trusts were an early form of mutual fund, with the “mother” investment house investing a small amount of capital in their offspring, highly leveraged using other people’s money.” (L. Wray 2011b, 4)

The financial system present in the United States in the 1920s evolved from stable to fragile rather quickly, and the “whirlwinds of optimism and pessimism” led many involved in the market to engage in several deceptive practices. The trust funds discussed above were extremely popular among a number of specialty investment firms on Wall Street. However, these firms were actually just partnerships, and were therefore unable to issue stock directly. They did receive, however, income through fees, and they could purchase a significant amount of stock in publicly traded companies. As a result, the investment trusts consisted of stocks in other firms – as Wray notes, however, they were often stocks in other affiliates that only held shares in Wall Street trusts – and would sell shares in the trusts to the public. (L. Wray 2011b) The investment firms would “pump” up a speculative bubble surrounding the funds in order to pocket the capital gains and then “dump” them at just the right time before the bubble burst. Furthermore, in a situation similar to what the nation would experience in the years leading up to the Global Financial Crisis of 2007, banks and investment firms profited greatly by selling tranches of toxic assets in the market. A notable example of this occurred when National City Bank discovered some bad Latin American loans on its books and proceeded to have its investment subsidiary repackage the loans and sell them to unknowing investors as new securities. (FDIC 2006)

The inefficiency of the entire capitalist economy and its players from post-WWI through the 1920s was referred to by Minsky as “… the failed model of the pre 1930s era.” (Minsky 1992, 37) Appropriate considering it resulted in the Great Depression – a worldwide economic downturn that hits the U.S. at the end of 1929 and lasts until 1939. The social and cultural effects are extraordinary, and to date it is the longest and most severe depression in the history of the nation.

1929-1933

The U.S. economy continued to spiral out of control. This four-year period was indeed, as Minsky wrote, “… the failure of capitalism between 1929 and 1933.” (Minsky 1992, 37) Considering the “attempts” made by government, in particular the Federal Reserve Bank and the Hoover administration, to stop the economic tailspin, it is obvious why Minsky made this statement.

Prior to the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation – the FDIC – more than 10,000 banks fail in the four years following the stock market crash of 1929 resulting in “… losses to depositors of about $1.3 billion.” (FDIC 2006) However, a large portion of the bank failures could have been prevented had the U.S. Central Bank acted quickly. As worried depositors rushed to withdrawl their savings from the banking system in the four years following the crash, “… the Federal Reserve failed to live up to the expectation that it would be an effective lender of last resort”. (Minsky 2008, 56) Indeed, a major function of the Federal Reserve Bank, which was established in 1913, is to act as a lender of last resort. In short, this function authorizes the Central Bank to intervene during a banking crisis – a bank run, for example – and provide emergency lending without limit. The instability in the financial system increased demand for Treasury Securities. The banking system was so fragile and on the verge of collapse, “the interest rate on U.S. Treasury bills goes negative because investors are willing to take a loss if they know that their money is safe.” (FDIC 2006)

Furthermore, new international trade policies increased the duration and severity of the Great Depression. In 1930, the Hoover administration enacts the Hawley-Smoot tariff act “… to increase the protection afforded domestic farmers against foreign agricultural imports.” (U.S. Department of State n.d.) The Act raises U.S. tariffs on imports resulting in a dramatic decline in international trade. The Act provoked retaliation from foreign governments and “… did nothing to foster trust and cooperation among nations in either the political or economic realm during a perilous era in international relations.” (U.S. Department of State n.d.)

Paternalistic Capitalism and the “New Deal” Reforms

In March of 1933, President Roosevelt takes office and promises “a new deal for the American people.” The centerpiece of the Roosevelt reform platform was to enact a comprehensive set of regulations to provide safety and soundness to the financial system, completely changing the nature of banking. Before addressing the banking system, “the programs of the first years of Roosevelt’s New Deal were mainly motivated, rationalized, and defended on humanitarian grounds.” (Minsky 2008, 134) Non-financial reform programs included the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), and the National Recovery Investment Act (NIRA); or, as Wray appropriately dubbed them, an “alphabet soup of programs.” (L. Wray 2011b, 4)

The Banking Act of 1933 (“Glass-Steagall Act”)

In an attempt to stabilize and strengthen the financial system, congress agreed to the most comprehensive overhaul of the banking industry in the nation’s history: the Banking Act of 1933 (Public Law 73-66, 48 STAT 162). The primary purpose of the Act, better known as Glass-Steagall, was to promote a safe financial environment in two ways: through the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and by preventing “…commercial banks from being exposed to the dangers which inevitably followed upon their participation in investment banking.” (A.G. Becker Inc. v. Board of Governors of Federal Reserve System 1982, 5) Preventing the exposure of commercial banks and their deposits from these dangers was accomplished by separating commercial banking and investment banking. “The integrity of the public’s holding of deposits in banks was to be insured by prohibiting deposit takers from these activities, and by preventing banks engaged in these activities from taking deposits.” (Kregel 2012, 5) Furthermore, the Act also prohibits commercial banks from paying interest on checking accounts, a measure intended to shelter banks from any additional risk that would accompany extending their liability structures.

The FDIC becomes a temporary agency in January of 1934 and establishes the deposit insurance level at $2,500 (six months later, that level was increased to $5,000). The Act gives the FDIC the important responsibility of supervising the banking system, leading to the creation of an FDIC branch in each state. (FDIC 2006) Bank runs become a lesser threat to the banking industry after the establishment of the FDIC, with only nine insured banks failing in 1934. (FDIC 2006)

Minsky labeled the period from 1933 through the end of WWII the “paternalistic” capitalism stage. This era of capitalism is characterized by “Big Government” policies and spending, as well as dramatic changes to the financial system, including:

countercyclical fiscal policy, which sustained profits when the economy faltered: low interest rates and interventions by the Federal Reserve unconstrained by gold-standard considerations; … ; establishment of a temporary, national investment bank (the Reconstruction Finance Corporation) to infuse government equity into transportation, industry and finance; and interventions by specialized organizations created to address sectoral concerns (such as those in housing and agriculture). (Minsky and Whalen 1996, 3)

These government supports played an extremely important role in the evolution of the capitalist economy – not only was the government the main source of financing for the economy, but the indebtedness of firms and households was very low due to the significant deflation that resulted from the Great Depression. The elimination of debts, combined with the government’s deficit, allowed for a significant increase in private sector saving. This resulted in an extended period of stability for the financial system and capitalist economy in the United States.

Money-manager Capitalism

There was a cautious use of debt by many households and firms in the early post-war period, arguably because memories of the Great Depression were inhibiting risky behavior. The stability faded shortly after WWII, however, because “… as the period over which the economy did well began to lengthen, margins of safety in indebtedness decreased and the system evolved toward a greater reliance on debt relative to internal finance, as well as toward the use of debt to acquire existing assets. As a result, the once robust financial system became increasingly fragile.” (Minsky and Whalen 1996, 4)

This is a good time to introduce Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis, a topic that is relevant considering the stability experienced during the post-war period. The hypothesis has two theorems:[i]

- A capitalist economy has both stable financial positions and unstable financial positions; and

- the economy transitions from a stable financial position to an unstable financial position during times of prolonged prosperity.

Before discussing them specifically, it is important to understand how these financial positions originate.

Capitalist economies are financial systems, and they depend upon investment and debt to create capital assets and initiate production. Specifically, “… a capitalist economy is accompanied by exchanges of present money for future money.” (Minsky 1992b, 2) In other words, investment is essential in the capital development of the economy, and investment is characterized by the creation of assets and liabilities through the process of borrowing and lending. Hence, present money is used by firms to finance their investment in the production of output, and future money represents the profits from selling the output. The lending process creates liabilities, or “IOUs”[ii], so it is important to note that the financing of investment is actually the financing of liabilities. As Minsky notes, “a part of the financing of the economy can be structured as dated payment commitments in which banks are the central player.” (Minsky 1992b, 3) In the case of bank lending, a financial relationship is formed when a bank lends to a firm, resulting in the creation of assets and liabilities. When a firm approaches a bank for a loan, a demand deposit is created. This demand deposit represents a liability of the bank and an asset of the firm. From the perspective of both the bank and the firm, the relationship is centered on profits. Hence, “the flow of money to [the] firm is a response to expectations of future profits, … and profit realizations determine whether the commitments in financial contracts are fulfilled …” (Minsky 1992b, 3-4)

The same can be said for every unit within the financial system – households, businesses, governments, banks and non-bank institutions have liabilities, or debts, that must be validated by cash flows. This means that sufficient income is required over a particular time to cover the repayment of interest and principal on a debt. Minsky identifies three types of relationships between a unit’s cash flows and its liabilities: hedge, speculative, and “Ponzi.” (Minsky 1992b) Hedge units possess sufficient and consistent cash flows that allow them to meet the payment obligations of their liabilities. Speculative units possess cash flows that allow them to meet interest payments that come due, but not principal, and therefore must roll-over, or refinance, the principal (issue new debt to meet the commitments of maturing debt, for example). Finally, a “Ponzi” unit is unable to make payments on the interest or principal amounts, and therefore is forced to either sell assets or increase indebtedness. As Minsky notes, “a unit that Ponzi finances lowers the margin of safety that it offers the holders of its debts.” (Minsky 1992b, 7)

The evolution of these positions determines the stability, or fragility, of the overall economy. During the initial stages of a stable period, hedge-financing units are assumed to dominate. Eventually, however, “over a “run of good times,” firms (and households) are encouraged to move from hedge to speculative finance, and the economy as a whole transitions from one in which hedge finance dominates to one with a greater weight of speculative finance.” (L. R. Wray 2011a, 4) As noted above, speculative units must continually refinance their positions in assets. However, if the ability to refinance is disrupted, then the speculative units can quickly transition to Ponzi units and a collapse of asset values is likely to occur because those units will need to “make position by selling out position.”

As discussed earlier, Glass-Steagall created a clear separation amongst the banks within the financial system based on their primary functions. In the years after WWII, however, this distinction deteriorated. As the financial system evolved, Minsky identified four types of banks: commercial banks, investment banks, universal banks, and public holding company models. [iii] Commercial banks issue short-term loans, which they finance by issuing short-term liabilities (demand and savings deposits).

Commercial banks, as Minsky notes, are important not only because of their size, but also because of their connection to the money supply. Control of the money supply is an important difference between the orthodox and heterodox approaches to economic theory. Orthodox theory, in particular the Monetarist position, treats the money supply as an exogenously controlled variable, which assumes the government can “control” the money supply and the target interest rate. The most notable example is Milton Friedman’s “quantity theory of money” approach, in which, by increasing the money supply, the monetary authorities “fool” workers into supplying more labor and can achieve a temporary increase in output and temporary reduction in unemployment. Heterodox theory, however, in particular Modern Money Theory (MMT), shares the endogenous approach that the central bank cannot control the money supply, but rather must accommodate the demand for reserves initiated through the banking system. However, MMT does take the central bank’s overnight target interest rate (the fed funds rate) as exogenous in the control sense: the Federal Reserve can set the target rate to any level it wishes. In other words, MMT subscribes to the “endogenous money, horizontal reserve” approach. (Although it is a topic beyond the scope of this paper, the Federel Reserve has been exogenously increasing bank reserves since the Fall of 2008 through a process known as Quantitative Easing[iv].) Getting back to Minsky, his view of money creation is that of MMT’s, and “changes in the quantity of money arise out of interactions among economic units that desire to spend in excess of their income and banks that facilitate such spending.” (Minsky 2008, 253) It is important to note, however, that banks do not lend reserves. Banks decide whether to lend based on the expectation of repayment. If expectation of return is high, banks will make the loan and seek reserves later.

Investment banking can be separated into two models:

In the first, the investment bank holds the equities and bonds issued by the corporation that requires financing of its capital stock. The investment bank in turn finances its position by issuing debt and shares held by households. If the investment bank’s debt is shorter term than the assets it holds, it must be able to refinance its position as discussed above. … [Hence] the investment bank will be successful only to the extent that its corporate borrowers are successful. Alternatively the investment bank simply places debt and equities of corporations into the portfolios of households. This model of investment banking does not require borrower success; rather than asking whether the borrower will repay the loan, this investment banker only worries whether he can sell the stocks and bonds he needs to place. (L. R. Wray 2010b, 7)

It is important to note that, in the second investment bank model, underwriting is no longer essential because the risk to the bank is eliminated once the stocks and bonds are removed from its balance sheet.

The universal bank model can also be separated into two types: a bank that engages in both commercial banking activities and investment banking activities, and a Public Holding Company (PHC) model. (L. R. Wray 2010b) In the first model, the investment bank lends to households and also lends to corporations by purchasing their stocks and bonds. This model can also be involved in real estate lending and insurance. The PHC model is one “… in which the holding company owns various types of financial firms with some degree of separation provided by firewalls. The PHC holds stocks and bonds of firms and finances positions by borrowing from banks, the market, and the Treasury.” (L. R. Wray 2010b, 8) Wray also notes that the evolution of the financial system towards “money-manager” capitalism allowed these three models to merge into one unit.

Fast forwarding a bit, the deregulation that occurred in the late 1990s, when New-Deal financial reforms were eliminated in favor of a more “free-market” environment, has allowed money managers to create various forms of mysterious investments for their own personal gain in a process known as “financialization” – which is characterized by “… growing debt that leverages income flows and wealth.” (L. R. Wray 2011a, 7) For perspective, total debt in the US was three times GDP in 1929; it reached five times GDP in 2007. These mysterious investments included asset-backed securities, credit default swaps, collateralized debt obligations, and several other types of interconnected “securitized” investments that increased leverage throughout the entire financial system. Securitization is the process of creating a financial instrument by combining several financial assets and selling them in bundles to investors. These bundles are referred to as asset-backed-securities. This became a common practice within the banking industry, and it allowed banks to lower their underwriting standards because, once the assets are repackaged and sold, they no longer pose a risk to the bank. This is commonly referred to as the “originate and distribute” model of lending. As Wray points out, “… Minsky pointed the finger at securitization. In the 1980s, the thrifts, which were not holding mortgages and had lowered underwriting standards, had funding capacity that flowed into commercial real estate; in the 2000s, the mania for risky (high-return) asset-backed securities fueled subprime lending.” (L. R. Wray 2010a)

Furthermore, the evolution of the capitalistic economy has led to managed money controlling a greater share of the financial system than that controlled by banks. Indeed, as Wray notes, “commercial banks and savings institutions have become a smaller share of the financial sector as seen from the relative shrinking of their assets.” (Wray and Nersisyan 2010, 7) However, concentration within the banking industry placed a significant amount of power in the hands of a few “mega banks.” In a working paper written by Wray, he indicates, “Minsky argued that the convergence of the various types of banks within the umbrella bank holding company and within shadow banks was fueled by growth of money manager capitalism.” (L. R. Wray 2011c, 15)

Reform

As Wray points, before discussing reform, we must understand the essential functions that the financial system is to provide. These functions are as follows:[v]

- A safe and sound payments system;

- short-term loans to households and firms, and, possibly, to state and local governments;

- a safe and sound housing finance system;

- a range of financial services including insurance, brokerage, and retirement services; and

- long-term funding of positions in expensive capital assets. (L. R. Wray 2010b, 22)

In the banking system that has evolved since the end of WWII, it was common for one bank to provide many of these services. Minsky notes, however, “in creating a financial structure that aids and abets the capital development of an economy, specialized financial institutions, each of which has a well-defined primary domain, are necessary.” (Minsky 1992a, 25-26) Minsky also felt community banks, with their focus on resource creation, should be at the heart of the financial structure. These banks would follow a “relationship banking” model that promotes the capital development of the economy. To accomplish this, “he advocated government policies to support a network of small community development banks (public-private partnerships) that would provide a full range of services.” (L. R. Wray 2010a)

Furthermore, as discussed above, competition from deposit-taking investment banks left commercial banks with no choice but to “… increase their fee and commission incomes by moving lending to unrelated affiliates, and off their balance sheets.” (Kregel 2008, 11) This resulted in the “originate and distribute” model that deteriorated underwriting standards. The policy recommendation, therefore, is to eliminate this model by forcing banks to hold the assets on their balance sheets until maturity, thereby exposing them to the longer-term risks. This exposure will promote better underwriting practices. “Decentralization plus maintaining exposure to risk could reorient institutions back toward relationship banking.” (L. R. Wray 2010b, 24)

Finally, access to reserves and the Fed’s discount window should be granted to institutions who are not affiliated, in any way, with investment banking. Access to federal funds allowed these institutions to leverage risky investments with “house money” and forced the Federal Reserve to extend the function of lender of last resort far beyond what was necessary in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 (GFC).

In conclusion, the most important characteristic of any capitalist economy is that it is a constantly evolving financial system. Minsky felt, as the economy evolves, so too must economic policy. He notes it is important for policy makers to not forget “… the valuable lessons of the past, lessons that include: 1.) capitalism comes in many varieties; 2.) the institutions established through public policy play a vital role in determining what form capitalism takes; and 3.) laissez-faire is a prescription for economic disaster.” (Minsky and Whalen 1996, 8) The future has yet to be determined; however, the state of the banking system in the years following the GFC has yet to see the restrictions promised by the current administration. Although one could be optimistic, the divide in Washington and the world of mainstream economics appears to have other plans.

[i] As described in “The Financial Instability Hypothesis.” (Minsky 1992b)

[ii] L. Randall Wray, in several of writings, uses the term “IOU” when referring to a liability. For reference see his 2012 book on Modern Money Theory (L. R. Wray 2012)

[iii] As described by Wray in “What Do Banks Do? What Should Banks Do?” (L. R. Wray 2010b)

[iv] Quantitative Easing is a new “monetary policy tool” used by the Federal Reserve Bank that is characterized by large scale asset purchases (including agency mortgage backed securities, agency debt, and long term government bonds) in an attempt to stimulate economic activity by reducing various interest rates. For more information, see:

[v] As described by Wray in “What Do Banks Do? What Should Banks Do?” (L. R. Wray 2010b)

[i] As presented in Modern Macroeconomics (Snowdon and Vane 2006, 38)

[ii] Professor Eugene Fama of the University of Chicago was awarded the 2013 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2013. He and two other economists were recognized for their analysis of asset prices. For more information, see

[iii] See “Credit Expansion, 1920 to 1929, and its Lessons”, Charles E. Persons, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Nov., 1930), pp. 94-130

*A Note:

For the next few weeks we will be running a series of articles on monetary theory and policy. These are final essays written by MA students in my class this past Fall semester. I was very happy with the results—students indicated that they had a firm grasp of both the orthodox approach as well as the heterodox approach to the subject. Most of them also included some Modern Money Theory in their answers. I asked about half of the students in the class if they would like to contribute their essay to this series. Sometimes students are the best teachers because they see things with a fresh eye and cut to what is important. They are usually less concerned with esoteric academic debates than are their professors. Note that these contributions are voluntary and are written by Masters students. I told students they could choose to use their own names, or they could choose an alias. Comments are welcome, but please be nice—remember these are students.

For your reference, here were the topics for the paper. The paper had a maximum limit of 6000 words.

Choose one of the following. You must consider and address both the orthodox approach and the heterodox approach in your essay. Where relevant, include various strands of each.

A) What is the nature of money? Given the nature of money, what approach should be taken to policy-making?

B) What is the nature of banking? Given the nature of banking, what approach should be taken to policy-making?

C) According to John Smithin there are several main themes throughout controversies of monetary economics, each typically addressed by each of the various approaches to monetary theory and policy. In your essay, discuss how each of the approaches we covered this semester tackles these themes enumerated by Smithin.

L. Randall Wray

References

A.G. Becker Inc. v. Board of Governors of Federal Reserve System. 693 F.2d 136 (United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, 1982).

FDIC. FDIC: Learning Bank. May 02, 2006. (accessed December 1, 2013).

Kregel, Jan. “Minsky’s Cushions of Safety: Systemic Risk and the Crisis in the U.S. Subprime Mortgage Market.” Public Policy Brief No. 93. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, 2008.

—. “No Going Back: Why We Cannot Restore Glass-Steagall’s Segregation of Banking and Finance.” Public Policy Brief No. 101. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, 2012.

Minsky, Hyman P. “Financial Crises: Systemic or Idiosyncratic.” Working Paper No. 51. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, April 1991.

—. Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. Ney York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

—. “The Capital Development of the Economy and the Structure of Financial Institutions.” Financial Fragility and the US Economy, Annual Meetings, American Economic Association. New Orleans, 1992a.

—. “The Economic Problem at the End of the Second Millenium: Creating Capitalism, Reforming Capitalism, Making Capitalism Work.” Hyman P. Minsky Archive. April 29, 1993.

—. “The Financial Instability Hypothesis.” Working Paper No. 74. Annondale-on-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, May 1992b.

—. “Uncertainty and the Institutional Structure of Capitalist Economies.” Working Paper No. 155. April 1996.

Minsky, Hyman P., and Charles J. Whalen. “Economic Insecurity and the Institutional Prerequisites for Successful Capitalism.” Working Paper No. 165. May 1996.

Persons, Charles E. “Credit Expansion, 1920 to 1929, and its Lessons.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 45, No. 1 (November 1930): 94-130.

Snowdon, Brian, and Howard R. Vane. Modern Macroeconomics: Its Orgins, Development and Current State. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc., 2006.

U.S. Department of State. Smoot-Hawley Tariff. n.d. (accessed December 1, 2013).

Wray, L. Randall. “Minsky Crisis.” Working Paper No. 659. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, March 2011a.

—. “Minsky’s View of Capitalism and Banking in America.” One-Pager | No. 6. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, November 12, 2010a.

—. “Minsky’s Money Manager Capitalism and the Global Financial Crisis.” Working Paper No. 661. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, March 2011b.

—. Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems. 2012.

—. “The Financial Crisis Viewed through the Theory of Social Costs.” Working Paper No. 662. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, March 2011c.

—. “What Do Banks Do? What Should Banks Do?” Working Paper No. 612. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, August 2010b.

Wray, L. Randall, and Yeva Nersisyan. “The Global Financial Crisis and the Shift to Shadow Banking.” Working Paper No. 587. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, February 2010.

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: On the Na...

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: On the Na...

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: On the Na...

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: on the Nature of Banking - EXPOSING BLACK TRUTH