Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

February 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

Should Ben Bernanke be retained as Fed Chairman?

This week, we will be running a series of essays on TIME Magazine’s ‘Person of the Year’, discussing whether he deserves to be reappointed as Chairman of the Federal Reserve. The first of these installments – posted below – comes from Marshall Auerback. Tomorrow’s installment comes from Warren Mosler.

Why Bernanke Must Go

There are any number of reasons why Ben Bernanke should not be reconfirmed, notwithstanding the vote in his favor by the Senate committee last week.

1. Let’s start by using some criteria laid out by Bernanke himself. When first nominated as chairman of the Federal Reserve, Mr. Bernanke promised a greater degree of transparency than his predecessor, but has completely stonewalled anybody seeking to obtain clarification of the events surrounding the credit crisis and more specifically, the role of the Federal Reserve. Any information disclosed would have facilitated a proper assessment of Bernanke’s job performance (which is probably one of the reasons the Fed chairman doesn’t want it released) and, more importantly, would have created a foundation for useful forensic work to prevent recurrences going forward.

Understanding what the decision-making was prior to and during the crisis is key to evaluating Bernanke’s performance and to improving performance in general. Post mortems are standard in sports and medicine. Why not here? And, more importantly, why does Bernanke continue to oppose it? Even the Swiss National Bank has provided a higher level of disclosure and transparency on the banking crisis to its public than has hitherto been agreed by the Bernanke Fed.

2. The Fed chairman claims unique expertise on the grounds of his scholarship of the Great Depression. Few have actually challenged him on the basis of these academic credentials, yet Bernanke holds these out as if they are manifest proof of his appropriateness for the position as head of the Federal Reserve. Ironically, even though Bernanke drew heavily on the work of both Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz for his own scholarship of the period, Ms Schwartz herself has been enormously critical of the Fed’s conduct both pre-crisis and in seeing providing liquidity as the primary solution. She also warned explicitly against drawing comparisons between the gold standard era Depression and now. Additionally, Bernanke’s reading of the Depression (which is pretty conventional, that the Fed blew it by not providing more liquidity) ascribed little significance to fiscal policy, which has led Bernanke toward wrongheaded “solutions” such as “quantitative easing” and an alphabet soup of lending facilities, none of which did anything to enhance aggregate demand. Consistent with that, the Fed chairman been on the wrong side of fiscal policy, urging the Congress to balance the budget, at least longer term, which suggests that he learned nothing of the fiscal successes of the New Deal.

3. Bernanke’s consistent advocacy of “quantitative easing” perpetuates the silly notion that the Fed has had something to do with the economic “recovery” (a line which Time Magazine had readily embraced in its selection of the Fed Chairman as “Person of the Year”). He has ascribed little importance to the existence of the automatic stabilizers and indeed has persistently fed the misguided notion that the Federal government had limited fiscal resources.

The mainstream belief is that quantitative easing will stimulate the economy sufficiently to put a brake on the downward spiral of lost production and the increasing unemployment. But as Bill Mitchell as pointed out, quantitative easing merely involves the central bank buying longer dated higher yielding bonds in exchange for deposits made by the central bank in the commercial banking system – that is, crediting their reserve accounts: “[QE] is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantitative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates.” In the real world, the creation of a loan and (concurrently) a deposit by a bank are in no way constrained by the quantity of reserves. Instead, the terms set by the central bank for acquiring reserves (which then also affects the rates banks borrow at in money markets) affect a bank’s profit margin on a newly created loan. Thus, expanding its balance sheet can create a potential short position in reserves, and thus the profitability of newly created loans, not the bank’s ability to create the loan.

Banks, then, lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. Even the BIS recognizes this. Unfortunately our Federal Reserve chairman either does not know this (in which case his ignorance disqualifies him for another term in office) or he deliberately misrepresents the actual benefits of QE (duplicity being another good ground for disqualification for a 2nd term). The current incoherence of our economic policy making could diminish if we had a Fed chairman who understood the importance of fiscal policy, rather than one who downplays its significance. Which leads to point 4 below.

4. The Fed chairman continues to demonstrate a tremendous conceptual confusion at the heart of the current crisis, particularly in regard to the banking sector. He actively supported TARP on the grounds that repairing the banks balance sheets would somehow “unblock” credit flows and thereby enhance economic activity. The whole notion of repairing bank balance sheet is a lie and misdirection. The balance sheets we should want to see repaired are household balance sheets. Banks have failed us profoundly. We want them reorganized, not repaired. This will never happen as long as this apologist for Wall Street remains head of the Fed. A world in which the banks are all fixed but households are still broken is worse than what we have right now. Too-big-to-fail banks restored to health are too-big-to-fail banks restored to power. The idea that fixing legacy banks is prerequisite to fixing the broad economy is a lie perpetrated by, amongst others, the Federal Reserve Chairman.

For all of these reasons, Bernanke must go.

Posted in Marshall Auerback, Monetary policy, Uncategorized

Tagged Marshall Auerback, Monetary policy

Michael Hudson Responds to Paul Krugman

By Michael Hudson, Distinguished Visiting Professor, UMKC

I have recently republished my lecture notes on the history of theories of Trade Development and Foreign Debt. (Available from Amazon) In this book, I provide the basis for refuting Samuelson’s factor-price equalization theorem, IMF-World Bank austerity programs, and the purchasing-parity theory of exchange rates.

These ideas were lapses back from earlier analysis, whose pedigree I trace. In view of their regressive character, I think that the question that needs to be asked is how the discipline was untracked and trivialized from its classical flowering? How did it become marginalized and trivialized, taking for granted the social structures and dynamics that should be the substance and focal point of its analysis? As John Williams quipped already in 1929 about the practical usefulness of international trade theory, “I have often felt like the man who stammered and finally learned to say ‘Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers’ but found it hard to work into conversation.” But now that such prattling has become the essence of conversation among economists, the important question is how universities, students and the rest of the world have come to accept it and even award prizes in it!

To answer this question, my book describes the “intellectual engineering” that has turned the economics discipline into a public relations exercise for the rentier classes criticized by the classical economists: landlords, bankers and monopolists. It was largely to counter criticisms of their unearned income and wealth, after all, that the post-classical reaction aimed to limit the conceptual “toolbox” of economists to become so unrealistic, narrow-minded and self-serving to the status quo. It has ended up as an intellectual ploy to distract attention away from the financial and property dynamics that are polarizing our world between debtors and creditors, property owners and renters, while steering politics from democracy to oligarchy.

Bad economic content starts with bad methodology. Ever since John Stuart Mill in the 1840s, economics has been described as a deductive discipline of axiomatic assumptions. Nobel Prizewinners from Paul Samuelson to Bill Vickery have described the criterion for economic excellence to be the consistency of its assumptions, not their realism.[2] Typical of this approach is Nobel Prizewinner Paul Samuelson’s conclusion in his famous 1939 article on “The Gains from International Trade”:

“In pointing out the consequences of a set of abstract assumptions, one need not be committed unduly as to the relation between reality and these assumptions.”[3]

This attitude did not deter him from drawing policy conclusions affecting the material world in which real people live. These conclusions are diametrically opposed to the empirically successful protectionism by which Britain, the United States and Germany rose to industrial supremacy.

Typical of this now widespread attitude is the textbook Microeconomics by William Vickery, winner of the 1997 Nobel Economics Prize:

“Economic theory proper, indeed, is nothing more than a system of logical relations between certain sets of assumptions and the conclusions derived from them… The validity of a theory proper does not depend on the correspondence or lack of it between the assumptions of the theory or its conclusions and observations in the real world. A theory as an internally consistent system is valid if the conclusions follow logically from its premises, and the fact that neither the premises nor theconclusions correspond to reality may show that the theory is not very useful, but does not invalidate it. In any pure theory, all propositions are essentially tautological, in the sense that the results are implicit in the assumptions made.”[4]

Such disdain for empirical verification is not found in the physical sciences. Its popularity in the social sciences is sponsored by vested interests. There is always self-interest behind methodological madness. That is because success requires heavy subsidies from special interests, who benefit from an erroneous, misleading or deceptive economic logic. Why promote unrealistic abstractions, after all, if not to distract attention from reforms aimed at creating rules that oblige people actually to earn their income rather than simply extracting it from the rest of the economy?

NOTES:

[1] John H. Williams, Postwar Monetary Plans and Other Essays, 3rd ed. (New York: 1947), pp. 134f.

[2] I have surveyed the methodology in “The Use and Abuse of Mathematical Economics,” Journal of Economic Studies 27 (2000):292-315. I earlier criticized its application to international economic theorizing in Trade, Development and Foreign Debt (1992; new ed. ISLET, 2009), especially chapter 11.

[3] Paul Samuelson “The Gains from International Trade,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, Vol. 5 (1939), p. 205.

[4] William Vickery, Microeconomics (New York: 1964), p. 5.

Krugman Gets it Wrong

In his column in yesterday’s NYT, Professor Paul Krugman rose to the defense of Paul Samuelson. He argued that Michael Hudson’s piece, originally published in 1970, not only misunderstood Samuelson’s theories but also wrongly asserted that he was not deserving of a Nobel. Krugman’s main argument was that Samuelson’s version of “Keynesian” economics offered a solution to depressions that pre-existing “institutionalist” theory did not have:

Faced with the Depression, institutional economics turned out to have very little to offer, except to say that it was a complex phenomenon with deep historical roots, and surely there was no easy answer. Meanwhile, model-oriented economists turned quickly to Keynes — who was very much a builder of little models. And what they said was, “This is a failure of effective demand. You can cure it by pushing this button.” The fiscal expansion of World War II, although not intended as a Keynesian policy, proved them right. So Samuelson-type economics didn’t win because of its power to cloud men’s minds. It won because in the greatest economic crisis in history, it had something useful to say.

This claim is bizarre, to say the least. First, Roosevelt’s New Deal was in place before Keynes published his General Theory, and it was mostly formulated by the American institutional economists that Krugman claims to have been clueless. (There certainly were clueless economists—those following the neoclassical approach, traced to English “political economy”.)

Second, it was Alvin Hansen, not Paul Samuelson, who brought Keynesian ideas to America. And Hansen retained the more radical ideas (such as the tendency to stagnation) that Samuelson dropped. Further, Hansen was—surprise, surprise—working within the institutionalist tradition (as documented by in a book by Perry Mehrling).

Third, many other institutionalists also adopted Keynesian ideas in their work—before Samuelson’s simplistic mathematization swamped the discipline. For example, Dudley Dillard—a well-known institutionalist—wrote the first accessible interpretation of Keynes in 1948; Kenneth Boulding’s 1950 Reconstruction of Economics served as the basis for four editions of his Principles book—on which a generation of American economists was trained (again, before Samuelson’s text took over). It is in almost every respect superior to Samuelson’s text. I encourage Professor Krugman to take a look.

Fourth, Hyman Minsky (who first trained with institutionalists at the University of Chicago—before it became a bastion of monetarist thought) took Samuelson’s overly simplistic multiplier-accelerator approach and extended it with institutional ceilings and floors. He quickly grew tired of the constraints placed on theory by Samuelsonian mathematics and moved on to develop his Financial Instability Hypothesis (which Krugman has admitted he finds interesting, even if he does not fully comprehend it). I ask you, how many analysts have turned to Samuelson’s work to try to understand the current crisis—versus the number of times Minsky’s work has been invoked?

And fifth, Samuelson’s “button” approach to dealing with the business cycle has been thoroughly discredited since the late 1960s—when he announced that we would never have another recession. In truth, as Minsky argued, it is not possible to “fine-tune” the economy because “stability is destabilizing”. The simplistic “Keynesian” approach propagated by the likes of Samuelson leaves out the behavioral and institutional analysis that is necessary to deal with instability and crisis.

Sixth, as has been long recognized, Samuelson purposely threw Keynes out of his analysis as he developed the “Neoclassical Synthesis”. The name dropping was intentional—Keynes was too radical for the cold warrior Samuelson. At best, what Samuelson presented was a highly bastardized version of Keynes—as Joan Robinson termed it, a Bastard Keynesian approach (we know the mother was neoclassical economics but we do not know who the father was).

Finally, and most telling of all, whose work is universally acknowledged as the most insightful analysis of the Great Depression? Might it be John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Great Crash? I have never heard anyone refer to any work of Samuelson in that context.

So Professor Krugman has got it wrong.

Bernanke Believes Monodisciplinary Means Multidisciplinary

This column arose from research about President Obama’s proposed reappointment of Dr. Bernanke as Fed Chair. Bernanke was faced recently with the choice of who to make the head of Fed supervision. The context of that choice is extremely important and will be the subject of a longer essay. He made the choice, on October 20, 2009. He is lobbying for the passage of bills that would make the Fed the uberregulator in charge of safety & soundness and systemic risk regulation, so the importance of the top supervisor was extraordinary. As a future column will explain, the person he choose was exceptionally poor and demonstrates that Bernanke was not only one of the major architects of the current crisis – he is the primary architect of the next crisis. Bernanke made a theoclassical economist, Patrick M. Parkinson, the head of Fed supervision. The future essay will show that this long-time Fed economist has a track record of failure because of his fundamentalist beliefs in the gospel of anti-regulation and resultant naïve beliefs that “sophisticated” market participants are impervious to fraud.

This essay focuses on Bernanke’s explanation of why he chose Parkinson to be the Fed’s lead uberregulator. Bernanke is faced with an impossible task. Parkinson has never been a regulator, knows nothing about how to be an effective regulator, thinks that fraud (which causes the greatest banking losses) virtually does not exist, and has consistently proposed anti-regulatory policies that have proved disastrous. Bernanke has to explain why he has chosen, for the most important professional supervisory position in the world, an individual who he should have quietly asked to resign. Here is how he pitched (October 20, 2009) the appointment of one of the vast array of failed Fed economists as uberregulator:

“As an economist with deep expertise in financial markets, Pat Parkinson will be an important asset at a time when we are focusing on a multidisciplinary approach to banking supervision and regulation,” Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke said. “We’re working to supervise the banking sector in a way that focuses not just on individual institutions, but on how those institutions are interconnected and are integrated into the financial system and the economy. Pat is the right person to lead the division as we develop these new methods.”

If you know the Fed then you already get the hilarity of this comment and the arrogance and inanity it reveals. Parkinson is monodisciplinary, not multidisciplinary. He opines that fraud cannot exist among “sophisticated” parties even though the criminology literature has documented such fraud for over half a century as has all human experience including, recently, Drexel/Milken and Enron, et al. Because he is monodisciplinary and because he has no experience as a regulator (and because he is a theoclassical zealot) he has no idea that other fields have falsified his creed. He is not even aware that his own agency’s examiners, ever since the Fed was created, have repeatedly falsified his navie beliefs about fraud.

The joke, of course, is that the Fed has long failed as a regulator not because of its examiners but because of its senior leadership’s four crippling weaknesses.

- The regional Federal Reserve Banks, which provide most examination and supervision, have conflicts of interest that we already decided, in the context of the Federal Home Loan Banks, was unacceptable. The fact that this conflict continues demonstrates the vastly greater political power of the banks compared to S&Ls.

- The Board of the Governors of the Federal Reserve has, traditionally, made supervision at best a tertiary concern. Monetary policy and international dealings with sister central banks is what mattered. (Now) Treasury Secretary Geithner’s response to a question by Representative Ron Paul about his regulatory experience as President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York epitomizes the senior Fed mindset: “I’ve never been a regulator….” True, but you’re not supposed to admit it.

- The Federal Reserve, at all levels, is far too close to the industry it is supposed to regulate. It has been taught for years to view the industry as “the customer.”

- Theoclassical economists dominate both the Board of Governors and the senior staff. The fact that this is considered normal and appropriate demonstrates how damaging that domination is. Theoclassical economists are very bad economists that cause recurrent, intensifying crises – but they are even worse anti-regulators.

Bernanke’s claim that putting a theoclassical economist in charge of supervision would fix the Fed’s pathetic anti-regulatory non-actions that were critical to causing the bubble and the Great Recession is an insult to the Fed’s examiners and professional supervisors. The claim that Parkinson needs to run supervision is implicitly a claim that none of the examiners or supervisors understands “how these institutions are interconnected and are integrated into the financial system and the economy.” Only someone with a doctorate in economics can understand those complex matters. Bernanke’s answer to the Fed’s anti-regulatory failures that arise because theoclassical economists dominate the agency is greater domination by those same anti-regulatory economists.

The arrogance and the bias of a monodisciplinary and theoclassical economist’s assurance that his field exclusively holds the answers is staggering. Let us be clear: Greenspan, Bernanke, Geithner, and Parkinson share many characteristics. They are all theoclassical zealots that ignored other fields, and other perspectives within their own discipline. They share an intense anti-regulatory bias. They are all naïve about fraud. None of them understood “how these institutions are interconnected and integrated into the financial system and the economy.” They were all abject failures at regulatory policy. The Fed’s anti-regulatory creed was so destructive precisely because it never understood banks, banking, criminology, and finance.

But Bernanke’s claim that an economist brings unique strengths to supervision is false on another substantive dimension. Greenspan, Bernanke, Geithner, and Parkinson did not simply miss systemic risk. They all missed garden-variety fraud and other forms of credit risk at individual banks. If they had identified and prevented those frauds and undue credit risks there would have been no systemic risk. Without the fraudulent underlying mortgage loans there would not have been a severe housing bubble, mass delinquencies, and the “underlying” that supposedly “backed” the toxic collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). This was an easy crisis to prevent. If the old rules on underwriting had been kept in force and enforced there would have been no crisis. It was the theoclassical economists that claimed that the toxic product was really manna and that the toxic derivatives spread the manna optimally.

What the Fed desperately needs is true multidisciplinary strength. Fraud causes the bulk of bank losses. White-collar criminologists are the experts in this field and have important insights into where “epidemics” of fraud will occur, why such epidemics hyper-inflate financial bubbles, and how to fight such frauds. It turns out that theoclassical economists’ anti-regulatory policy prescriptions optimize a “criminogenic environment” that produces these epidemics and hyper-inflated bubbles. Why don’t the Fed and its sister agencies have a “chief criminologist?”

Elegant Theories That Didn’t Work

The Problem with Paul Samuelson

By MICHAEL HUDSON

“First Published on counterpunch.org“

“The following article was written in 1970 after Samuelson received the award”

Paul Samuelson, America’s best known economist, died on Sunday. He was awarded the Nobel prize for economics, (founded one year earlier by a Swedish bank in 1970 “in honor of Alfred Nobel”). That award elicited this trenchant critique, published by Michael Hudson in Commonweal, December 18, 1970. The essay was titled “Does economics deserve a Nobel prize? (And by the way, does Samuelson deserve one?)”

It is bad enough that the field of psychology has for so long been a non-social science, viewing the motive forces of personality as deriving from internal psychic experiences rather than from man’s interaction with his social setting. Similarly in the field of economics: since its “utilitarian” revolution about a century ago, this discipline has also abandoned its analysis of the objective world and its political, economic productive relations in favor of more introverted, utilitarian and welfare-oriented norms. Moral speculations concerning mathematical psychics have come to displace the once-social science of political economy.

To a large extent the discipline’s revolt against British classical political economy was a reaction against Marxism, which represented the logical culmination of classical Ricardian economics and its paramount emphasis on the conditions of production. Following the counter-revolution, the motive force of economic behavior came to be viewed as stemming from man’s wants rather than from his productive capacities, organization of production, and the social relations that followed therefrom. By the postwar period the anti-classical revolution (curiously termed neo-classical by its participants) had carried the day. Its major textbook of indoctrination was Paul Samuelson’s Economics.

Today, virtually all established economists are products of this anti-classical revolution, which I myself am tempted to call a revolution against economic analysis per se. The established practitioners of economics are uniformly negligent of the social preconditions and consequences of man’s economic activity. In this lies their shortcoming, as well as that of the newly-instituted Economics Prize granted by the Swedish Academy: at least for the next decade it must perforce remain a prize for non-economics, or at best superfluous economics. Should it therefore be given at all?

This is only the second year in which the Economics prize has been awarded, and the first time it has been granted to a single individual — Paul Samuelson — described in the words of a jubilant New York Times editorial as “the world’s greatest pure economic theorist.” And yet the body of doctrine that Samuelson espouses is one of the major reasons why economics students enrolled in the nation’s colleges have been declining in number. For they are, I am glad to say, appalled at the irrelevant nature of the discipline as it is now taught, impatient with its inability to describe the problems which plague the world in which they live, and increasingly resentful of its explaining away the most apparent problems which first attracted them to the subject.

The trouble with the Nobel Award is not so much its choice of man (although I shall have more to say later as to the implications of the choice of Samuelson), but its designation of economics as a scientific field worthy of receiving a Nobel prize at all. In the prize committee’s words, Mr. Samuelson received the award for the “scientific work through which he has developed static and dynamic economic theory and actively contributed to raising the level of analysis in economic science. . . .”

What is the nature of this science? Can it be “scientific” to promulgate theories that do not describe economic reality as it unfolds in its historical context, and which lead to economic imbalance when applied? Is economics really an applied science at all? Of course it is implemented in practice, but with a noteworthy lack of success in recent years on the part of all the major economic schools, from the post-Keynesians to the monetarists.

In Mr. Samuelson’s case, for example, the trade policy that follows from his theoretical doctrines is laissez faire. That this doctrine has been adopted by most of the western world is obvious. That it has benefited the developed nations is also apparent. However, its usefulness to less developed countries is doubtful, for underlying it is a permanent justification of the status quo: let things alone and everything will (tend to) come to “equilibrium.” Unfortunately, this concept of equilibrium is probably the most perverse idea plaguing economics today, and it is just this concept that Mr. Samuelson has done so much to popularize. For it is all too often overlooked that when someone falls fiat on his face he is “in equilibrium” just as much as when he is standing upright. Poverty as well as wealth represents an equilibrium position. Everything that exists represents, however fleetingly, some equilibrium — that is, some balance or product — of forces.

Nowhere is the sterility of this equilibrium preconception more apparent than in Mr. Samuelson’s famous factor-price equalization theorem, which states that the natural tendency of the international economy is for wages and profits among nations to converge over time. As an empirical historical generality this obviously is invalid. International wage levels and living standards are diverging, not converging, so that the rich creditor nations are becoming richer while poor debtor countries are becoming poorer — at an accelerating pace, to boot. Capital transfers (international investment and “aid”) have, if anything, aggravated the problem, largely because they have tended to buttress the structural defects that impede progress in the poorer countries: obsolete systems of land tenure, inadequate educational and labor-training institutions, pre-capitalist aristocratic social structures, and so forth. Unfortunately, it is just such political-economic factors that have been overlooked by Mr. Samuelson’s theorizing (as they have been overlooked by the mainstream of academic economists since political economy gave way to “economics” a century ago).

In this respect Mr. Samuelson’s theories can be described as beautiful watch parts which, when assembled, make a watch that doesn’t tell the time accurately. The individual parts are perfect, but their interaction is somehow not. The parts of this watch are the constituents of neoclassical theory that add up to an inapplicable whole. They are a kit of conceptual tools ideally designed to correct a world that doesn’t exist.

The problem is one of scope. Mr. Samuelson’s three volumes of economic papers represent a myriad of applications of internally consistent (or what economists call “elegant”) theories, but to what avail? The theories are static, the world dynamic.

Ultimately, the problem resolves to a basic difference between economics and the natural sciences. In the latter, the preconception of an ultimate symmetry in nature has led to many revolutionary breakthroughs, from the Copernican revolution in astronomy to the theory of the atom and its sub-particles, and including the laws of thermodynamics, the periodic table of the elements, and unified field theory. Economic activity is not characterized by a similar underlying symmetry. It is more unbalanced. Independent variables or exogenous shocks do not set in motion just-offsetting counter-movements, as they would have to in order to bring about a meaningful new equilibrium. If they did, there would be no economic growth at all in the world economy, no difference between U.S. per capita productive powers and living standards and those of Paraguay.

Mr. Samuelson, however, is representative of the academic mainstream today in imagining that economic forces tend to equalize productive powers and personal incomes throughout the world except when impeded by the disequilibrating “impurities” of government policy. Empirical observation has long indicated that the historical evolution of “free” market forces has increasingly favored the richer nations (those fortunate enough to have benefited from an economic head start) and correspondingly retarded the development of the laggard countries. It is precisely the existence of political and institutional “impurities” such as foreign aid programs, deliberate government employment policies, and related political actions that have tended to counteract the “natural” course of economic history, by trying to maintain some international equitability of economic development and to help compensate for the economic dispersion caused by the disequilibrating “natural” economy.

This decade will see a revolution that will overthrow these untenable theories. Such revolutions in economic thought are not infrequent. Indeed, virtually all of the leading economic postulates and “tools of the trade” have been developed in the context of political-economic debates accompanying turning points in economic history. Thus, for every theory put forth there has been a counter-theory.

To a major extent these debates have concerned international trade and payments. David Hume with the quantity theory of money, for instance, along with Adam Smith and his “invisible hand” of self-interest, opposed the mercantilist monetary and international financial theories that had been used to defend England’s commercial restrictions in the eighteenth century. During England’s Corn Law debates some years later, Malthus opposed Ricardo on value and rent theory and its implications for the theory of comparative advantage in international trade. Later, the American protectionists of the 19th century opposed the Ricardians, urging that engineering coefficients and productivity theory become the nexus of economic thought rather than the theory of exchange, value and distribution. Still later, the Austrian School and Alfred Marshall emerged to oppose classical political economy (particularly. Marx) from yet another vantage point, making consumption and utility the nexus of their theorizing.

In the 1920s, Keynes opposed Bertil Ohlin and Jacques Rueff (among others) as to the existence of structural limits to the ability of the traditional price and income adjustment mechanisms to maintain “equilibrium,” or even economic and social stability. The setting of this debate was the German reparations problem. Today, a parallel debate is raging between the Structuralist School which flourishes mainly in Latin America and opposes austerity programs as a viable plan for economic improvement of their countries, and the monetarist and post-Keynesian schools defending the IMF’s austerity programs of balance-of-payments adjustment. Finally, in yet another debate, Milton Friedman and his monetarist school are opposing what is left of the Keynesians (including Paul Samuelson) over whether monetary aggregates or interest rates and fiscal policy are the decisive factors in economic activity.

In none of these debates do (or did) members of one school accept the theories or even the underlying assumptions and postulates of the other. In this respect the history of economic thought has not resembled that of physics, medicine, or other natural sciences, in which a discovery is fairly rapidly and universally acknowledged to be a contribution of new objective knowledge, and in which political repercussions and its associated national self-interest are almost entirely absent. In economics alone the irony is posed that two contradictory theories may both qualify for prizeworthy preeminence, and that the prize may please one group of nations and displease another on theoretical grounds.

Thus, if the Nobel prize could be awarded posthumously, both Ricardo and Malthus, Marx and Marshall would no doubt qualify, just as both Paul Samuelson and Milton Friedman were leading contenders for the 1970 prize. [Friedman got his Nobel in 1976.] Who, on the other hand, can imagine the recipient of the physics or chemistry prize holding a view not almost universally shared by his colleagues? (Within the profession, of course, there may exist different schools of thought. But they do not usually dispute the recognized positive contribution of their profession’s Nobel prizewinner.) Who could review the history of these prizes and pick out a great number of recipients whose contributions proved to be false trails or stumbling blocks to theoretical progress rather than (in their day) breakthroughs?

The Swedish Royal Academy has therefore involved itself in a number of inconsistencies in choosing Mr. Samuelson to receive the 1970 Economics Prize. For one thing, last year’s prize was awarded to two mathematical economists (Jan Tinbergen of Holland and Ragnar Frisch of Norway) for their translation of other men’s economic theories into mathematical language, and in their statistical testing of existing economic theory. This year’s prize, by contrast, was awarded to a man whose theoretical contribution is essentially untestable by the very nature of its “pure” assumptions, which are far too static ever to have the world stop its dynamic evolution so that they may be “tested.” (This prompted one of my colleagues to suggest that the next Economics Prize be awarded to anyone capable of empirically testing any of Mr. Samuelson’s theorems.)

And precisely because economic “science” seems to be more akin to “political science” than to natural science, the Economics Prize seems closer to the Peace Prize than to the prize in chemistry. Deliberately or not, it represents the Royal Swedish Academy’s endorsement or recognition of the political influence of some economist in helping to defend some (presumptively) laudable government policy. Could the prize therefore be given just as readily to a U.S. president, central banker or some other non-academician as to a “pure” theorist (if such exists)? Could it just as well be granted to David Rockefeller for taking the lead in lowering the prime rate, or President Nixon for his acknowledged role in guiding the world’s largest economy, or to Arthur Burns as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board? If the issue is ultimately one of government policy, the answer would seem to be affirmative.

Or is popularity perhaps to become the major criterion for winning the prize? This year’s award must have been granted at least partially in recognition of Mr. Samuelson’s Economics textbook, which has sold over two million copies since 1947 and thereby influenced the minds of a whole generation of — let us say it, for it is certainly not all Mr. Samuelson’s fault — old fogeys. The book’s orientation itself has impelled students away from further study of the subject rather than attracting them to it. And yet if popularity and success in the marketplace of economic fads (among those who have chosen to remain in the discipline rather than seeking richer intellectual pastures elsewhere) is to become a consideration, then the prize committee has done an injustice to Jacqueline Susann in not awarding her this year’s literary prize.

To summarize, reality and relevance rather than “purity” and elegance are the burning issues in economics today, political implications rather than antiquarian geometrics. The fault therefore lies not with Mr. Samuelson but with his discipline. Until it is agreed what economics is, or should be, it is as fruitless to award a prize for “good economics” as to award an engineer who designed a marvelous machine that either could not be built or whose purpose was unexplained. The prize must thus fall to those still lost in the ivory corridors of the past, reinforcing general equilibrium economics just as it is being pressed out of favor by those striving to restore the discipline to its long-lost pedestal of political economy.

*At the time I wrote this critique I was teaching international trade theory at the Graduate Faculty of the New School for Social Research at the time. Subsequently, I criticized Mr. Samuelson’s methodology in “The Use and Abuse of Mathematical Economics,” Journal of Economic Studies 27 (2000):292-315. Most important of all is Mr. Samuelson’s factor-price equalization theorem. I finally have republished my Trade, Development and Foreign Debt: A History of Theories of Polarization v. Convergence in the World Economy.

Michael Hudson is a former Wall Street economist. A Distinguished Research Professor at University of Missouri, Kansas City (UMKC), he is the author of many books, including Super Imperialism: The Economic Strategy of American Empire (new ed., Pluto Press, 2002) He can be reached via his website, [email protected]

Is It Time to Reduce the Ease to Prevent Inflation and Possible National Insolvency?

The growing consensus view is that the worst is behind us. The Fed’s massive intervention finally quelled the liquidity crisis. The fiscal stimulus package has done its work, saving jobs and boosting retail sales. The latest data show that net exports are booming. While residential real estate remains moribund, there are occasional reports that sales are picking up and that prices are firming. Recovery is just around the corner.

Hence, many have started to call on the Fed to think about reversing its “quantitative ease”—that is, to remove some of the reserves it has injected into the banking system. Further, most commentators reject any discussion of additional fiscal stimulus on the argument that it is no longer needed and would likely increase inflation pressures. Thus, the ARRA’s stimulus package should be allowed to expire and Congress ought to begin thinking about raising taxes to close the budget deficit.

Still, there remain three worries: unemployment is high and while job losses have slowed all plausible projections are for continued slack labor markets for months and even years to come; state and local government finances are a mess; and continued monetary and fiscal ease threaten to bring on inflation and perhaps even national insolvency.

Me thinks that reported sightings of economic recovery are premature. Still, let us suppose that policy has indeed produced a resurrection. What should we do about unemployment, state and local government shortfalls, and federal budget deficits? I will be brief on the first two topics but will provide a detailed rebuttal to the belief that continued monetary ease as well as federal government deficits might spark inflation and national insolvency.

1. Unemployment

Despite the slight improvement in the jobs picture (meaning only that things did not get worse), we need 12 million new jobs just to deal with workers who have lost their jobs since the crisis began, plus those who would have entered the labor force (such as graduating students) if conditions had been better. At least another 12 million more jobs would be needed on top of that to get to full employment—or, 24 million total. Even at a rapid pace of job creation equal to an average of 300,000 net jobs created monthly it would take more than six years to provide work to all who now want to work (and, of course, the labor force would continue to grow over that period). There is no chance that the private sector will sustain such a pace of job creation. As discussed many times on this blog, the only hope is a direct job creation program funded by the federal government. This goes by the name of the job guarantee, employer of last resort, or public service employment proposal. (see here, here, and here)

2. State and Local Government Finance

Revenues of state and local governments are collapsing, forcing them to cut services, lay-off employees, and raise fees and taxes. Problems will get worse in coming months. Most property taxes are infrequently adjusted, and many governments will be recognizing depressed property values for the first time since the crisis began. Lower assessed values will mean much lower property tax revenues next year, compounding fiscal distress. Ratings agencies have begun to downgrade state and local government bonds—triggering a vicious downward spiral because interest rates rise (and in some cases, downgrades trigger penalties that must be paid by governments—to those same financial institutions that caused the crisis). Note that contractual obligations, such as debt service, must be met first. Hence, state and local governments have to cut noncontractual spending like that for schools, fire departments, and law enforcement so that they can use scarce tax revenue to pay interest and fees to fat cat bankers. As government employees lose their jobs, local communities not only suffer from diminished services but also from reduced retail sales and higher mortgage delinquencies—again pushing a vicious cycle that collapses tax revenue.

The solution, again, must come from the federal government, which is the only entity that can spend countercyclically without regard to its tax revenue. As discussed on this blog in several posts (here and here), one of the best ways to provide funding would be in the form of federal block grants to states on a per capita basis—perhaps $400 billion next year. A payroll tax holiday would also help—increasing take-home pay of employees and reducing employer costs on all employees covered by Social Security.

3. Federal Budget Deficit, Insolvency, and Inflation

Resolving the unemployment and state and local budget problems will require help from the federal government. Yet that conflicts with the claimed necessity of tightening fiscal and monetary policy in order to preempt inflation and solvency problems. Two former Fed Chairmen have weighed in on US fiscal and monetary policy ease and the dangers posed. On NBC’s Meet the Press, Alan Greenspan argued:

“I think the Fed has done an extraordinary job and it’s done a huge amount (to bolster employment). There’s just so much monetary policy and the central bank can do. And I think they’ve gone to their limits, at this particular stage. You cannot ask a central bank to do more than it is capable of without very dire consequences,”

He went on, claiming that the US faces inflation unless the Fed begins to pull back “all the stimulus it put into the economy.”

In an interview (with SPIEGEL ONLINE – News – International) former Chairman Paul Volcker said the deficit will need to be cut:

Volcker: You’ve got to deal with the deficit and you’ve got to deal with it in a timely way. Right now, with the unemployment rate still very high, excess capacity is still evident, and the economy is dependent on government money as we said. We are not going to successfully attack the deficit right now but we have got to prepare for attacking it.SPIEGEL: Should Americans prepare themselves for a tax increase?Volcker: Not at the moment, but I think we would have to think about it. The present tax system historically has transferred about 18 to 19 percent of the GNP to the government. And we are going to come out of all this with an expenditure relationship to GNP very substantially above that. We either have to cut expenditures and that means reducing entitlements and certainly defense expenditures by an amount that may not be possible. If you can do it, fine. If we can’t do it, then we have to think about taxes.

Both the Fed and the Treasury are said to be “pumping” too much money into the economy, sowing the seeds of future inflation. There are two kinds of cases made for the argument that monetary and fiscal policy are too lax. The first is based loosely on the old Monetarist view that too much money causes inflation., while the second is more Keynesian, pointing toward the money provided through the Treasury’s spending. The evidence can be found in the huge expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet to two trillion dollars of liabilities and in the Treasury’s budget deficit that has grown toward a trillion and a half dollars. Chairman Greenspan, a committed Monetarist, points to the first of these, recognizing that most of these Fed liabilities take the form of reserves held by banks—which will eventually start lending their excess reserves. Chairman Volcker points to the second—federal government spending that will create income that will be spent. Hence, those trillions of extra dollars provided by the Treasury and Fed surely will fuel more lending and spending, leading to inflation or even to a hyperinflation of Zimbabwean proportions.

Some have made a related argument: all those excess reserves in the banking system will be lent to speculators, fueling yet another asset price bubble. The consequence could be rising commodities prices (such as oil prices) feeding through to inflation of consumer and producer prices. Or, the speculative bubble would give way to yet another financial crisis. Worse, either inflation or a bursting bubble could generate a run out of the dollar, collapsing the currency—and off we go again toward Zimbabwean ruin.

Finally, over the past two decades the Fed—accompanied by New Consensus macroeconomists—has managed to create a widespread belief that inflation is caused by expected inflation. In other words, if everyone believes there will be inflation, then inflation will result because wages and prices will be hiked on the expectation that costs will rise. For this reason, monetary policy has long been directed toward managing inflation expectations, with the Fed convincing markets that it is diligently fighting inflation pressures even before they arise. Now, however, the Fed is in danger of losing the battle because all of those extra reserves in the banking system will create the expectation of inflation—which will itself cause inflation. For this reason, the Fed needs to begin raising interest rates and (or, by?) removing reserves from the banking system. That would prevent expected inflation from generating Zimbabwean hyperinflation.

Unfortunately, all these arguments misunderstand the situation. Here is why:

You cannot tell much of anything by looking at current bank reserve positions. As and when banks decide they do not need to hold so many reserves, they will begin to unwind them, repaying loans to the Fed (destroying reserves) and buying Treasuries (the Fed will accommodate by selling assets in order to keep the overnight fed funds rate on target—if it did not, excess reserves would drive the fed funds rate to zero).There are no direct inflationary pressures that result from such operations. Indeed, all else equal, the reserves will be reduced with no new bank lending or deposit creation.

Banks normally buy financial assets (including loan IOUs) by issuing liabilities (including deposits). As the economy recovers, banks will want to resume such activities. If there is a general demand to buy output or financial assets, coming from borrowers perceived to be creditworthy, banks normally accommodate by making loans. This does not require ex ante reserves (or even capital if regulators do not enforce capital requirements or if banks can move assets off balance sheet). Yes, such a process can generate rising asset prices and banks broadly defined might accommodate this as they seek profits through lending to speculators. In this respect you could argue that expected inflation of asset prices fuels actual inflation of asset prices since that can fuel a speculative run up. Yet, this can occur with or without any excess reserves–indeed even if banks were already short required reserves they could expand lending then go to Fed to get the reserves. In other words, banks do not lend reserves nor is their lending constrained by reserves. Thus, while it is true that banks can finance a speculative bubble in asset prices, they can do this no matter what their reserve position is.

Nor will bank lending for asset purchases necessarily generate inflation of output prices. Any implications of renewed bank lending for CPI or PPI inflation are contingent on pass through from commodities to output prices. If the speculative binge in, say, futures prices of commodities feeds through to commodities spot prices, and if this then pressures output price inflation (as measured by the CPI and PPI), there can be an effect on measured inflation. There are lots of caveats–due to the way these indexes are calculated, to the possibility of consumer and producer substitutions, and to offsetting price deflation pressures (Chinese production and all of that). In any case, if there is a real danger that the current commodities price boom could accelerate to the point that it might create a crash or output price inflation, the best course of action would be to constrain the speculation directly. This can be done through direct credit controls placed on lenders as well as regulation of speculators.

It is true that the Fed has operated on the belief that by controlling inflation expectations it prevents inflation. Low inflation, in turn, is supposed to generate robust economic growth and high employment. This has been exposed by the current crisis as an unwarranted belief. The Wizard of Oz behind the curtain was exposed as an impotent fraud—while Bernanke remained focused on controlling inflation expectations for far too long, the whole economy collapsed around him. It was only when he finally abandoned expectations management in favor of bold action—lending without limit to institutions that needed reserves—that he helped to quell the liquidity crisis. All of his subsequent actions have had no impact on the economy—“quantitative easing” is nothing but a slogan, meaning that the Fed accommodates the demand for reserves (which it has always done, and necessarily must do so long as it has an interest rate target and wants par clearing).

It is sheer folly to believe that inflation expectations lead to inflation and that by controlling the expectations one controls inflation. In the modern capitalist economy, prices of output are mostly administered, with the caveat that competitive pressures from low cost producers in China and India put downward pressure on prices that may force domestic sellers to cut prices. Hence, US inflation has remained low in recent years because there has been little cost pressure; and note that most countries around the world have also experienced low inflation over the same period even though they did not enjoy the supposed benefits of a Wizard in charge of monetary policy. In the current environment of a global financial and economic calamity, the real danger is price deflation. The bit of inflation we do experience is due almost entirely to energy price blips—which could be prevented if we would just prohibit pension funds from speculating in commodities.

Still, there remains one path to Zimbabwean hyperinflation: a collapse of the currency due to insolvency and default by our federal government on its debts. Yet, as many have discussed on this blog (see here, here, here, here, and here), the US government is the sovereign issuer of our dollar currency. It cannot be forced into bankruptcy because it services its dollar debt by crediting bank accounts. It can never run out of these credits, since they are merely electronic entries on balance sheets, created at the stroke of a computer key. It can, and will, make all payments as they come due. In short, federal government insolvency is not possible.

To be sure, as we have emphasized many times, too much government spending can be inflationary. But the measure of “too much” cannot be found by looking at the size of the deficit (or, equivalently, at the shortfall of tax revenue), or at the ratio of government spending to GDP, or at the outstanding debt stock. Rather, government spending will approach an inflation barrier as the economy approaches full employment of resources, including labor resources. Yet, we are no where near to full employment. Any fear that current levels of spending, or even much larger amounts of federal spending, might be inflationary are premature. With 12 to 25 million jobless workers remaining, inflation is not a legitimate worry.

You can be sure that no matter how misguided President Obama’s policies might be, he is not taking us down the path to a Zimbabwean hyperinflation. This is not the place for a detailed analysis of the probable course of the dollar. In coming months it might decline a bit, or rise a bit (I’d bet on the latter if I were a gambler)—but there will be no global run out of the dollar. For one thing, runners must run to something—and as recent reports suggest, Euroland’s prospects look dire. That leaves smallish nations (Japan, the UK—both with their own problems) or big nations (China, India) that are too risky for foreigners. The best place to park savings will remain the US dollar.

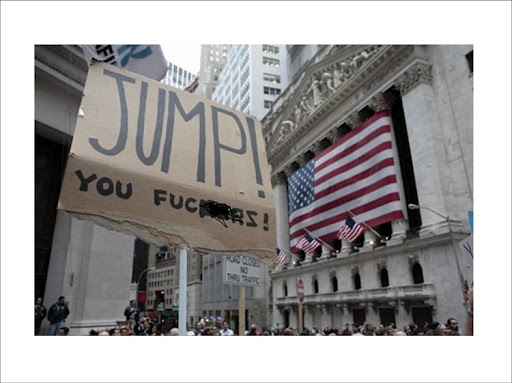

Obama Finds His Spine and Attacks Fat Cat Bankers

President Obama has finally castigated the fat cat bankers that caused the crisis that forced millions of Americans from their jobs and their homes. Let us hope this represents a much awaited reversal of his here-to-for prostration before Rubin’s Wall Street buddies. (See Matt Taibbi’s Obama’s Big Sellout)

Trends always begin with a first step. Now he must prove that he really means it by firing Timmy (why haven’t you resigned yet?) Geithner and Larry Summers for crimes against the economy. We might even hope for a more deserved outcome:

The next step will be to send the FDIC into the largest, “systemically dangerous”, financial institutions to shut them down. Fire all the top management plus any traders who have earned six figure bonuses in any of the past three years. Replace them with lowly paid middle management. We will need a new Jessie Jones (President Roosevelt’s selection to head the Reconstruction Finance Corporation that took over half of the nation’s banks in the Great Depression, successfully resolving most of them); my colleague, Bill Black (who helped to resolve the thrift crisis, standing up to Charles Keating, John McCain and the rest of the Keating 5), is the leading candidate. His task will be to downsize the financial sector, starting with the top two dozen or so banks—which will be broken into small pieces. Their former management and traders will be investigated for fraud, which will be found with a probability approaching certainty in all cases.

We will also need to round-up all the Goldman Sachs alum now working in government– shoveling favors to their former employer—for special treatment. Part of the President’s remaining stimulus funds can be devoted to building new prisons for them and the thousands of other financial market predators. The new penitentiaries ought to be sited in places like Modesto, California that are suffering the most from the real estate collapse, making use of foreclosed properties and providing jobs as prison guards to those who have been displaced. At their hands, poetic as well as Biblical justice could be visited on Wall Street’s finest.

The notion that these “highly skilled” whiz kids need huge bonuses to retain them is, as Keynes would remark “crazily improbable–the sort of thing which no man could believe who had not had his head fuddled with nonsense for years and years.” Your average Brooklyn plumber has more financial markets sense than all of these clowns combined. Their efforts were directed to another goal—running a kleptocracy that would make a Russian mobster blush. There is no evidence that they have learned anything from this debacle and unless they are removed, they will dig the financial black hole even deeper.

This is the real change we have been waiting for since Obama took office. The Obama elected by the American people has been AWOL since last November, with an evil twin occupying the White House and repaying Wall Street for its campaign contributions. However, America is still a democracy—one citizen, one vote—and Obama has got to realize that while the fat cats might have contributed most of the money, they did not provide many votes. It is time to boot the imposter and downsize Wall Street’s influence on Washington.

The electorate voted for change. I have the audacity of hope to believe that the real Obama is the one we saw this week. Send the fake back to Goldman’s.

Posted in L. Randall Wray, Policy and Reform, Uncategorized

Tagged L. Randall Wray, Policy and Reform

Obama’s New-Found Populism: All Hat, No Cattle

President Obama is taking a sharp, populist tone with Wall Street and scolding the ways of Washington as he once again looks to the Senate to follow the House and pass one of his top legislative priorities: sweeping financial regulatory reform. It might feel satisfying to hear the President criticize “reckless”, “fat cat” bankers, but the financial reform legislation passed by the House last Friday (and lauded by the President) provides little incentive to change their behavior. In reality populism, with nothing of substance behind it, is just cynical posturing designed to mask genuine failure. Like everything else with this President, he is again showing himself to be (to use an expression of his predecessor), all hat, no cattle.

Appealing to the peanut gallery at this stage is an insult to the voters’ intelligence. The current bill is yet another in a series of major disappointments. The most telling comment on the latest reforms came from the stock market: Bank stocks ended the day higher last Friday (when the House bill was passed to great fanfare), with the KBW Banks index slightly outperforming the benchmark Dow Jones industrial average.

At its most basic level, a bank is an entity that has a reserve account at the Fed, which makes loans and takes deposits. That is its primary public purpose, and we should not be allowing activities which undermine this central function, especially seeing as it is the government which guarantees the public’s deposits via the FDIC. (As an aside, even though the government creates all reserves and guarantees deposits, we do not want it to be directing lending activity because, as “Winterspeak” notes, “we do not want the Government to make credit decisions, they are too likely to dole out money to politically connected constituencies, while starving worthwhile, but unconnected borrowers”.

However good the political optics of resorting to name-calling and demonization of Wall Street, the legislation itself does nothing to recognize that the behavior criticized is a direct consequence of incentives built into the current institutional structure. It completely misses the point because it does nothing to ban activities which were at the heart of the crisis and which will likely be perpetuated as a consequence of the new legislation. All the new legislation does is institutionalize tax payer bailouts and, in so doing, continues the process of privatizing profits and socializing losses. There is no attempt to ban activities that were central to this crisis. The problem is that insolvent institutions have a habit of “betting the bank” through control fraud and the new legislation will not prevent this.

Even positive aspects of the bill, such as the establishment of the Consumer Financial Protection Agency, were significantly watered down. New Democrats – the people we used to call “Republicans” – won concessions that give federal regulators more scope to preempt state consumer-protection laws deemed to “significantly interfere with or materially impair a national bank’s ability to do business.” The change was sponsored by Congresswoman Melissa Bean, who is the most bought for and paid member (by bankers) in the House , not an inconsiderable political achievement amongst our current political profiles in courage in Congress. Bean justified the change on the basis of having, “robust national standards and enforcing them uniformly”, which sounds good until one considers the history of federal regulators, none of whom have historically moved when they plainly should have done so. How many federal regulators do you recall actually blocking the most egregious excesses in the mortgage market over the past 15 years? Preventing the states from moving proactively means that we will likely repeat the experience of the 1990s. Historically, the reform impetus has emanated from the states, not the Federal Government, Governor Eliot Spitzer’s administration being a prominent illustration.

More and more voters are beginning to believe this façade of reform is deliberate – a cynical act of kabuki theatre by the President to mask his own reticence to deal with the problem in an honest manner. It was clear to many of us that the President may not have been serious about reform when he picked Tim Geithner and Larry Summers as the leaders of his economic team a year ago, and essentially relegated any genuine progressive to the Cabinet equivalent of Siberia, as Matt Taibbi recently highlighted Yes, Summers and Geithner both have ample experience: but does that mean that they were qualified to take on the positions they were granted in the Administration? I suppose that depends on whether you think a doctor who botched your surgery ought to be given the role for the next one, simply because he has greater familiarity with your body than another surgeon.

Some on the left have attacked Taibbi very hard for the attacks on Obama, and Matt is no conservative. More importantly, he is correct: Taibbi calls the President for what he is, a sweet talking man who cannot fulfill one single promise he made to the public to get elected. So we have this incompetent financial reform bill, which will not place any limits on another systematic collapse. We have a health bill with no means of sensibly restraining cost pressures within the private health insurance industry. We are still fighting two wars, one of which is being escalated. The economy is still struggling and jobs are being lost.

Far easier to resort to cheap populism that actually do something about it. If the President were serious, he would be pointing out that the bankers have been undercutting every effort at reform, and have been paying off Congress to put loopholes into all legislation. If he were genuinely upset, he would be channeling the country’s anger constructively, by calling on the population to take to the streets in mass protests against Wall St with a view to shutting down the biggest banks and breaking their power once and for all. Of course the President would never do anything so “irresponsible”. Far better to throw a few bones to the peasants and hope that the appearance of reform pacifies them.

The economist Hyman Minsky argued that the Great Depression represented a failure of the small-government, laissez-faire economic model, while the New Deal promoted a Big Government/Big Bank highly successful model for capitalism. The current crisis just as convincingly represents a failure of the Big Government/Crony Capitalist model that promotes deregulation, reduced oversight, privatization, and consolidation of market power. Yet the very people, who have shredded the New Deal reforms and replaced them with self-supervision of markets, are the champions of today’s financial “reform”. As appealing as the story of Paul on the road to Damascus might be, there is no certainly no evidence of any Damascene conversion here amongst the policy makers of the Obama Administration. It’s business as usual, along with the championing of monetary and fiscal policy that is biased against maintenance of full employment and adequate growth to generate rising living standards for most Americans.

We must return to a more sensible model, with enhanced supervision of financial institutions and with a financial structure that promotes stability by aligning the banks’ activities with public purpose, rather than abetting speculation and then bailing the financial sector out after the fact. President Roosevelt proved that we could reform the financial system, rescue homeowners, and deal with the unemployed even as we mobilized and then fought World War II. By contrast, this is an Administration that defines reform as muddled compromise within a profoundly broken polity.

Posted in Marshall Auerback, Policy and Reform, Uncategorized

Tagged Marshall Auerback, Policy and Reform

Failed Economics Creates Failed Families

By June Carbone

Edward A. Smith/Missouri Chair of Law, the Constitution and Society, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Where is the economics of the family when we need it? Family instability magnifies societal inequality and undermines the foundation for the next generation. Yet, the ideas that helped secure a Nobel Prize in economics for Chicago economist Gary Becker, which still provide the starting point for every discussion of the economics of the family, have been proved wrong in almost every respect – and lay the foundation for an economy that looks like Yemen’s.

Becker won the Nobel Prize, at least in part, because of his identification of marriage with specialization and trade: men “specialize” in the market and women in the home. His critical prediction: with the wholesale movement of women into the labor market, the gains from marriage would decline and family instability would rise.

Yet, Becker’s theory cannot explain why the only group in society whose marriage rates have increased are college-educated women or why, contrary to Becker’s predictions, the divorce rates of two career college-educated couples have returned to the levels of the early sixties. Nor does it make any attempt to account for how class now dictates family form, with family stability increasingly a product of education and income. (For more on this, see Naomi Cahn and June Carbone, Red Families v. Blue Families.)

It has no hope of explaining these factors because it misses the most significant developments of the day. The idea that men “specialize” in the market is absurd. The very idea of the market as separate from the home is a product of nineteenth century industrialization, and the specialization that occurred in that era was a much greater investment in middle class males that increased the returns to education, enhanced differentiation among male workers, and magnified income inequality. The idea that women “specialize” in the home is even loonier – the female homemaker is the very epitome of the generalist, cleaning, cooking, mending and providing child care. While my husband “specializes” in corned beef and cabbage in contrast to my salads and tomato sauce, no one would confuse the result with professional accomplishments that are the result of decades of education and experience. (For more on this, see June Carbone, From Partners to Parents: The Second Revolution in Family Law.)

Ideas, however, have consequences, and a major one that follows from getting this wrong is understating the importance of investment in women. The big story of the last half century is greater returns to investment in women, investment that is derailed by early marriage and childbearing. The second, more pernicious consequence is that Becker misses the fact that what he characterizes as specialization rationalizes domination. Women’s domestic roles – including younger average ages of marriage, multiple children born in close succession, and the lack of external sources of income – correspond closely to a lack of power in relationships. As Nicholas Kristof writes in his inspiring accounts of women from the developing world, give women just a little bit more education and independence and they leave or reform abusive mates, producing healthier children and a more productive society.

In contrast, the policies that have tried to bring back Becker’s specialized family – which include abstinence education, the shot gun marriage, and declining access to family planning – simply ensure the U.S.’s declining economic competitiveness. Teenage girls in the red states that place single-minded emphasis on marriage are MORE likely than their blue state sisters to have sex and get pregnant, marry early and get divorced, stop going to school and go to work, and end up raising their children in poverty.

Comments Off on Failed Economics Creates Failed Families

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged Uncategorized