By L. Randall Wray

Last week we discussed denomination of government and private liabilities in the state money of account—the Dollar in the US, the Yen in Japan, and so on. We also introduced the concept of leverage, for example, the practice of holding a small amount of government currency in reserve against IOUs denominated in the state’s unit of account while promising to convert those IOUs to currency. This also led to a discussion of a “run” on private IOUs, demanding conversion. Since the reserves held are not nearly sufficient to meet the demand for conversion, the central bank must enter as lender of last resort to stop the run by lending its own IOUs to allow the conversions to take place. This week we examine bank clearing and the notion of a “pyramid” of liabilities with the government’s own IOUs at the top of that pyramid.

Clearing accounts extinguishes IOUs. Banks clear accounts using government IOUs, and for that reason either keep some currency on hand in their vaults, or more importantly maintain reserve deposits at the central bank. Further, they have access to more reserves should they ever need them, both through borrowing from other banks (called the interbank overnight market; this is the fed funds market in the US), or through borrowing them from the central bank.

All modern financial systems have developed procedures that ensure banks can get currency and reserves as necessary to clear accounts among themselves and with their depositors. When First National Bank receives a check drawn on Second National Bank, it asks the central bank to debit the reserves of Second National and to credit its own reserves. This is now handled electronically. Note that while Second National’s assets will be reduced (by the amount of reserves debited), its liabilities (checking deposit) will be reduced by the same amount. Similarly, when a depositor uses the ATM machine to withdraw currency, the bank’s assets (cash reserves) are reduced, and its IOUs to the depositor (the liabilities in the deposit account) are reduced by the same amount.

Other business firms use bank liabilities for clearing their own accounts. For example, the retail firm typically receives products from wholesalers on the basis of a promise to pay after a specified time period (usually 30 days). Wholesalers hold these IOUs until the end of the period, at which time the retailers pay by a check drawn on their bank account (or, increasingly, by an electronic transfer from their account to the account of the wholesaler). At this point, the retailer’s IOUs held by the wholesalers are destroyed.

Alternatively, the wholesaler might not be willing to wait until the end of the period for payment. In this case, the wholesaler can sell the retailer’s IOUs at a discount (for less than the amount that the retailer promises to pay at the end of the period). The discount is effectively interest that the wholesaler is willing to pay to get the funds earlier than promised.

Usually, it will be a financial institution that buys the IOU at a discount—called “discounting” the IOU (this is where the term “discount window” at the central bank comes from—the US Fed would buy commercial paper—IOUs of commercial firms–at a discount). In this case, the retailer will finally pay the holder of these IOUs (perhaps a financial institution) at the end of the period, who effectively earns interest (the difference between the amount paid for the IOUs and the amount paid by the retailer to extinguish the IOUs). Again, the retailer’s IOU is cancelled by delivering a bank liability (the holder of the retailer’s IOU receives a credit to her own bank account).

Pyramiding currency. Private financial liabilities are not only denominated in the government’s money of account, but they also are, ultimately, convertible into the government’s currency.

As we have discussed previously, banks explicitly promise to convert their liabilities to currency (either immediately in the case of demand deposits, or with some delay in the case of time deposits). Other private firms mostly use bank liabilities to clear their own accounts. Essentially, this means they are promising to convert their liabilities to bank liabilities, “paying by check” on a specified date (or, according to other conditions specified in the contract). For this reason, they must have deposits, or have access to deposits, with banks to make the payments.

Things can get even more complex than this, because there is a wide range of financial institutions (and, even, nonfinancial institutions that offer financial services) that can provide payment services. These can make payments for other firms, with net clearing among these “nonbank financial institutions” (also called “shadow banks”) occurring using the liabilities of banks. Banks, in turn, clear accounts using government liabilities.

There could, thus, be “six degrees of separation” (many layers of financial leveraging) between a creditor and debtor involved in clearing accounts.

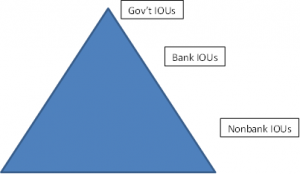

We can think of a pyramid of liabilities, with different layers according to the degree of separation from the central bank. Perhaps the bottom layer consists of the IOUs of households held by other households, by firms engaged in production, by banks, and by other financial institutions. The important point is that households usually clear accounts by using liabilities issued by those higher in the debt pyramid—usually financial institutions.

The next layer up from the bottom consists of the IOUs of firms engaged in production, with their liabilities held mostly by financial institutions higher in the debt pyramid (although some are directly held by households and by other production firms), and who mostly clear accounts using liabilities issued by the financial institutions.

At the next layer we have nonbank financial institutions, which in turn clear accounts using the banks whose liabilities are higher in the pyramid. Just below the apex of the pyramid, banks use government liabilities for net clearing.

Finally, the government is highest in the pyramid—with no liabilities higher than its inconvertible IOUs.

The shape of the pyramid is instructive for two reasons. First, there is a hierarchical arrangement whereby liabilities issued by those higher in the pyramid are generally more acceptable. In some respects, this is due to higher credit worthiness (the government’s liabilities are free from credit risk; as we move down the pyramid through bank liabilities, toward nonfinancial business liabilities and finally to the IOUs of households, risk tends to rise—although this is not a firm and fast rule).

Second, the liabilities at each level typically leverage the liabilities at the higher levels. In this sense, the whole pyramid is based on leveraging of (a relatively smaller number of) government IOUs. There are typically far more liabilities lower in the pyramid than there are high in the pyramid—at least in the case of a financially developed economy.

Note however that in the case of a convertible currency, the government’s currency is not at the apex of the pyramid. Since it promises to convert its currency on demand and at a fixed exchange rate into something else (gold or foreign currency), that “something else” is at the top. The consequences have been addressed in previous blogs: government must hold or at least have access to the thing into which it will convert its currency. As we will see in coming weeks, that can constrain its ability to use policy to achieve some policy goals such as full employment and robust economic growth.

Next week we will take a bit of a diversion to look at the strange case of Euroland. This is the biggest experiment the world has ever seen that attempts to subvert what Charles Goodhart has called the “one nation, one currency” rule. The members of the European Monetary Union each gave up their own sovereign, state, currencies to adopt the euro. While there have been other such experiments, they were small, usually temporary, and often an emergency measure. In the case of Euroland, however, we had strong, developed, rich, and reasonably healthy nations that voluntarily abandoned their sovereign currencies in favour of the euro. The experiment has not gone well. To say the least.