My fellow Americans,

let me get right to the point.

I have three bold new proposals to get back all the jobs we lost, and then some.

In fact, we need at least 20 million new jobs to restore our lost prosperity and put America back on top.

First let me state that the reason private sector jobs are lost is always the same.

Jobs are lost when business sales go down.

Economists give that fancy words- they call it a lack of aggregate demand.

But it’s very simple.

A restaurant doesn’t lay anyone off when it’s full of paying customers,

no matter how much the owner might hate the government,

the paper work, and the health regulations.

A department store doesn’t lay off workers when it’s full of paying customers,

And an engineering firm doesn’t lay anyone off when it has a backlog of orders.

Restaurants and other businesses lay people off when their customers stop buying, for any reason.

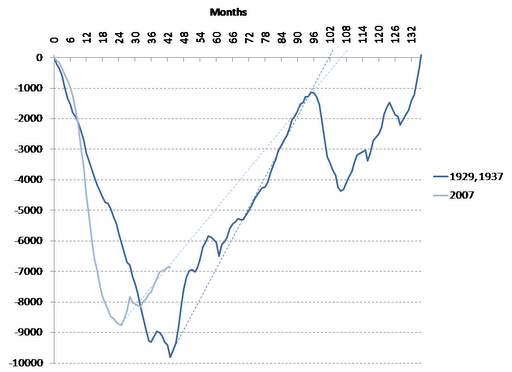

So the reason we lost 8 million jobs almost all at once back in 2008 wasn’t because all of a sudden

all those people decided they’d rather collect unemployment than work.

The reason all those jobs were lost was because sales collapsed.

Car sales, for example, collapsed from a rate of almost 17 million cars a year to just over 9 million cars a year.

That’s a serious collapse that cost millions of jobs.

Let me repeat, and it’s very simple, when sales go down, jobs are lost,

and when sales go up, jobs go up, as business hires to service all their new customers.

So my three proposals are specifically designed to get sales up to make sure business has a good paying job for anyone

willing and able to work.

That’s good for businesses and all the people who work for them.

And these proposals are bipartisan.

They are supported by Americans ranging from Tea Party supporters to the Progressive left, and everyone in between.

So listen up!

My first proposal if for a full payroll tax suspension.

That means no FICA taxes will be taken from both employees and employers.

These taxes are punishing, regressive taxes that no progressive should ever support.

And, of course, the Tea Party is against any tax.

So I expect full bipartisan support on this proposal.

Suspending these taxes adds hundreds of dollars a month to the incomes of people working for a living.

This is big money, not just a few pennies as in previous measures.

These are the people doing the real work.

Allowing them to take home more of their pay supports their good efforts.

Right now take home pay is barely enough to pay for food, rent, and gasoline, with not much left over.

When government stops taking FICA taxes out of their pockets,

they’ll be able to get back to more normal levels of spending.

And many will be able to better make their mortgage payments and their car payments,

which, by the way, is what the banks really want – people who can make their payments.

That’s the bottom up way to fix the banks, and not the top down bailouts we’ve done in the past.

And the payroll tax holiday is also for business,

which reduces costs for business,

which, through competition,

helps keep prices down for all of us, which means our dollars buy more than otherwise.

So a full payroll tax holiday means more take home pay for people working for a living,

and lower costs for business to help keep prices and inflation down,

so sales can go up and we can finally create those 20 million private sector jobs we desperately need.

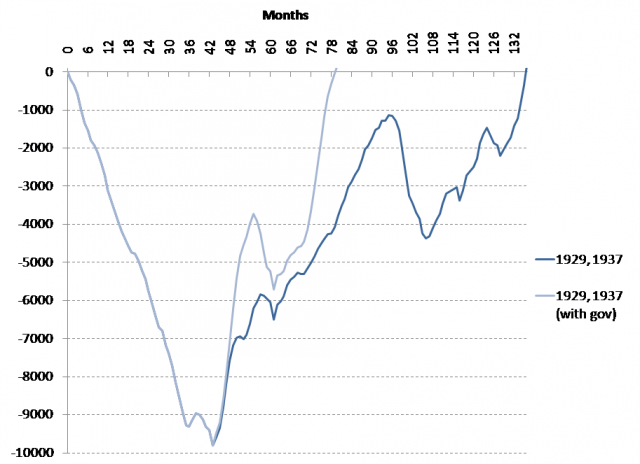

My second proposal is for a one time $150 billion Federal revenue distribution to the 50 state governments

with no strings attached.

This will help the states to fill the financial hole created by the recession,

and stay afloat while the sales and jobs recovery spurred by the payroll tax holiday

restores their lost revenues.

Again, I expect bipartisan support.

The progressives will support this as it helps the states sustain essential services,

and the Tea Party believes money is better spent at the state level than the federal level.

My third proposal does not involve a lot of money,

but it’s critical for the kind of recovery that fits our common vision of America

My third proposal is for a federally funded $8/hr transition job

for anyone willing and able to work,

to help the transition from unemployment to private sector employment.

The problem is employers don’t like to hire the unemployed,

and especially the long term unemployed.

While at the same time,

with the payroll tax holiday and the revenue distribution to the states,

business is going to need to hire all the people it can get.

The federally funded transition job allows the unemployed to get a transition job,

and show that they are willing and able to go to work every day,

which makes them good candidates for graduation to private sector employment.

Again, I expect this proposal to also get solid bipartisan support.

Progressives have always known the value of full employment,

while the Tea Party believes people should be able to work for a living, rather than collect unemployment.

Let me add here that nothing in these proposals expands the role or scope of the federal government.

The payroll tax holiday is a cut of a regressive, punishing tax,

that takes the government’s hand out of the pockets of both workers and business.

The revenue distribution to the states has no strings attached.

The federal government does nothing more than write a check.

And the transition job is designed to move the unemployed, who are in fact already in the public sector,

to private sector jobs.

There is no question that these three proposals will bring the increase in sales we need to

usher in a new era of prosperity and full employment.

The remaining concern is the federal budget deficit.

Fortunately, with the bad news of the downgrade of US Treasury securities by Standard and Poors to AA+ from AAA,

a very important lesson was learned.

Interest rates actually came down. And substantially.

And with that the financial and economic heavy weights from the 4 corners of the globe

made a very important point.

The markets are telling us something we should have known all along.

The US is not Greece for a very important reason that has been overlooked.

That reason is, the US federal government is the issuer of its own currency, the US dollar.

While Greece is not the issuer of the euro.

In fact, Greece, and all the other euro nations, have put themselves in the position of the US states.

Like the US states, Greece and other euro nations are not the issuer of the currency that they spend.

So they can run out of money and go broke, and are dependent on being able to tax and borrow to be able to spend.

But the issuer of its own currency, like the US, Japan, and the UK,

can always pay their bills.

There is no such thing as the US running out of dollars.

The US is not dependent on taxes or borrowing to be able to make all of its dollar payments.

The US federal government can not go broke like Greece.

That was the important lesson of the S and P downgrade,

and everyone has seen it up close and personal and they all now agree.

And now they all know why, with the deficit at record high levels, interest rates remain at record low levels.

Does that mean we should spend without limit and not tax at all?

Absolutely not!

Too much spending and not enough taxing will surely drive up prices and inflation.

But it does mean that right now,

with unemployment sky high and an economy on the verge of another recession,

we can immediately enact my 3 proposals to bring us back to

a strong economy with good jobs for people who want them.

And some day, if somehow there are too many jobs and it’s causing an inflation problem,

we can then take the measures needed to cool things down.

But meanwhile, as they say, to get out of hole we need to stop digging,

and instead implement my 3 proposals.

So in conclusion, let me repeat these three, simple, direct, bipartisan proposals

for a speedy recovery:

A full payroll tax holiday for employees and employers

A one time, per-capita, $150 billion revenue distribution to the states

And an $8/hr transition job for anyone willing and able to work to facilitate

the transition from unemployment to private sector employment as the economy recovers.

Thank you.