ADVICE TO PRESIDENT OBAMA AND PRIME MINISTER BROWN: Tell the IMF, the European Commission, and the Ratings Agencies to Take a Hike

By L. Randall Wray and Yeva Nersisyan

In recent days, articles in Der Speigel, the NYTimes, and the AP have all highlighted Neoliberal commentary warning of the dangers of growing budget deficits in the wealthiest nations—specifically in the US and the UK.

Marco Evers, writing in Der Speigel helpfully argues that the UK’s deficit to GDP ratio (at 12.9%) is actually larger than the ratio of Greece (12.2%), which is already in crisis. According to the AP report, the European Commission has somberly warned London to tighten its budget–to bring its deficit down to 3% of GDP by 2014-15 as promised–through higher fees and taxes, as well as cuts that “will be more drastic than those under (former Prime Minister) Margaret Thatcher”, according to economist Carl Emmerson. It should be remembered that Thatcher oversaw the downsizing of the UK economy, moving it to second-rate status so far as economies go. (In 1980 the UK’s per capita income was 79% of that of the US; by 1985 it had fallen below half. It is now the third largest economy in Europe, and sixth in the world—but it ranks 21st on the Human Development Index.) Apparently the EC would like to see the UK reduced to a third-rate economy—perhaps as punishment for dealing with the global financial crisis in more reasonable manner than the EC has. According to PricewaterhouseCoopers’s calculations, to cut the budget deficit in half by 2014, spending in most areas will have to be cut by 10% per year beginning next year. The EU warns that these cuts will have to be made even in an economic climate that could be “distinctly less favorable” than the UK is now assuming. In other words, fiscal tightening should be undertaken even without economic recovery. That ought to bring the profligate Brits to their knees!

Not to be outdone, the IMF’s John Lipsky (deputy managing director) “offered a grim prognosis for the world’s wealthiest nations, which are at a level of indebtedness not seen since the aftermath of World War II.” Even if fiscal stimulus is ended, he warned, debt ratios on average will rise to 110% by 2014. “Maintaining public debt at postcrisis levels could reduce potential growth in advanced economies by as much as half a percentage point annually.” And to reduce debt ratios appreciably will require an 8 percentage point swing, from structural deficits of 4% of GDP to surpluses of 4% annually by 2010. Note that in the case of the US, this would be equivalent to a reduction of national income by more than a trillion dollars. In other words, the Neoliberal doctors at the IMF recommend lots of pain.

Finally, Moody’s warned that the US and UK have moved closer to credit downgrades, negatively impacting their ability to borrow at favorable interest rates. Presumably, they can look to Greece and Portugal for lessons on the folly of ignoring the warnings of Neoliberal credit raters. Moody’s also warned that these nations cannot rely on growth alone to work their way out of debt. They will “require fiscal adjustments of a magnitude that, in some cases, will test social cohesion.” Moody’s repeated the assertion that the UK is relying on overly rosy economic forecasts—tax receipts will be lower than anticipated, hence the pain that Brown must inflict on his economy is higher—presumably high enough to provoke the kind of civil unrest we now see in Greece.

It is very hard to avoid the conclusion that the Neoliberals at the EU (which seems to act on these matters as a front for the Bundesbank), the IMF, and the ratings agencies are trying to do to the UK and US what they already did to Greece. A real conspiracy theorist might even wonder whether they are trying to succeed where the Third Reich could not—destruction of the US and UK economies in a bid to annihilate the nations themselves. Obviously, that is not a view we suggest. But if one were to adopt it, it could be noted that Neoliberals in Germany have been picking off its neighbors one-by-one, first Greece, then Portugal and Spain, then on to Italy and finally France. (

here) These Neoliberals use a combination of mercantilism—trade surpluses that suck demand and jobs out of its fellow EU nations—and then “market discipline” that punishes any nation that tries to fill resulting demand gaps with government spending. (

here) However, a more charitable interpretation is that it is the Teutonic Calvinism that guides EU prognostication on government deficits: today’s “excesses” must surely impose a tradeoff in the form of tomorrow’s costs. But when the EC begins to criticize UK and US policy, that is certainly a step that goes too far—even if it is simply due to muddled thought rather than to a nefarious agenda.

The ratings agencies are another matter altogether. These blessed every kind of Wall Street excess with triple A ratings. They never saw a NINJA loan they did not love. Yet, they are engaged in an ugly form of deficit terrorism, attacking one country after another, downgrading debt, raising interest rates and causing budget deficits to rise, which then pushes up credit default swap prices and triggers further downgrades. Ratings agencies serve no public purpose. They are thoroughly incompetent, and probably irredeemably fraudulent. They should be shut down, investigated, and prosecuted.

President Obama and PM Brown should “just say no” to the attempted intervention by these fundamentally misguided deficit hawks into their economic and political affairs. Not only would fiscal tightening now or even within the next several years be a monumental mistake, the notion that continued deficits threaten our economies is unsound. In the remainder of this piece we will briefly explain why. What these Neoliberals do not understand is that the UK and US operate with sovereign currencies—that is both of these nations issue their own non-convertible (floating exchange rate) currencies. For this reason the comparison with any nation that uses the Euro (such as Greece), or with a nation that pegs to precious metals or foreign currencies is invalid. In other words, there is no question of solvency or sustainability of deficits for the US and UK. Sovereign debt of these nations never carries default risk and hence cannot be rated below triple A.

Further, budget deficits are largely endogenously determined by economic performance, so that even if the US and UK adopted the Neoliberal recommendations, the budgetary outcome is not discretionary—indeed, tight fiscal policy would probably increase budget deficits by killing nascent economic recovery. Again, this would not raise any questions about solvency, but it certainly would impose unnecessary pain and sacrifice on the populations of the countries. Since we find it very difficult to believe that the ratings agencies, the IMF and the EU do not understand this, it is equally hard to avoid the conclusion that their policy recommendations are designed to subvert the economies of the US and UK. To what end we can only wonder.

Mr. Lipsky is certainly not alone in arguing that high debt levels will be detrimental for economic growth. A new and influential study by Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart, heavily publicized by the media, purports to show that once the gross debt to GDP ratio crosses the threshold of 90%, economic growth slows dramatically—by at least one percentage point. But the findings reported in Rogoff and Reinhart cannot be applied to the situation of the US or to the case of many other nations today—those that are not pegging their currency to gold or any other currency. Indeed, the Rogoff and Reinhart study is fatally flawed precisely because it does not recognize the difference between sovereign debt—debt of a national government that issues its own nonconvertible currency—and private debt or the debt issued by nonsovereign government that pegs its currency to precious metal or foreign currency (or Euro nations that adopt the euro).

Governments across the world have inflicted so many self-imposed constraints on public spending that the relatively simple operational realities behind public spending have been obscured. Most people tend to think that a balanced budget, be it for a household or a government, is a good thing, failing to make a distinction between a currency issuer and a currency user. Indeed, one of the most common analogies used by politicians and the media is the claim that a government is like a household: the household cannot continue to spend more than its income, so neither can the government. See

here for more on the differences between a household and a government. Yet that comparison is completely fallacious. Most importantly, households do not have the power to levy taxes, and to give a name to—and issue–the currency that those taxes are paid in. Rather, households are users of the currency issued by the sovereign government. Here the same distinction applies to firms, which are also users of the currency.

Operationally the sovereign government spends by crediting bank deposits (and simultaneously crediting the reserves of those banks) at its own central bank, in the case of the US, the Federal Reserve Bank. No household (or firm) is able to spend by crediting bank deposits and reserves, or by issuing currency. Households and firms can spend by going into debt if some entity will lend to them, which is something the national, sovereign government in no case requires when using its own currency. Unlike private debtors it can always make payments, including debt service payments, simply by changing numbers on its own spread sheet at its own central bank. This is a key to understanding why perpetual budget deficits are “sustainable” in the conventional sense of that term because government can always make any payments it desires on a timely basis.

A government that issues its currency that is not backed by any metal or pegged to another currency is not constrained in its ability to spend by the possibility that holders of dollars might ‘cash them in’ for gold, for example, as is the case with a gold standard. With a non-convertible sovereign currency, a government doesn’t need tax and bond revenues to protect its gold reserves—because it does not use gold reserves! While all governments today spend by crediting bank accounts and tax by debiting bank accounts, with convertible currencies budget deficits risk the loss of reserves, while with non-convertible sovereign currencies there is no such risk.

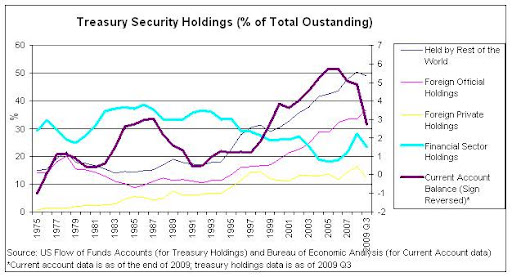

If we take the US as an example, its budget deficits add to the total of the outstanding stock of outstanding US Treasury securities, bank balances in their reserve accounts at the Federal Reserve Bank, and/or cash in circulation, together on a dollar for dollar basis. Treasury Securities are functionally nothing more than ‘time deposits’ at the Fed, held in what are called ‘securities accounts’ at the Fed. They are often measured relative to the size of GDP, as are the annual federal deficits, to help scale the nominal numbers to provide perspective. (Note this is often NOT done by those who try to scare the population with talk of “tens of trillions of dollars of unfunded entitlements” due to retirements of the babyboomers, rather than show those numbers as a % of future GDP.)

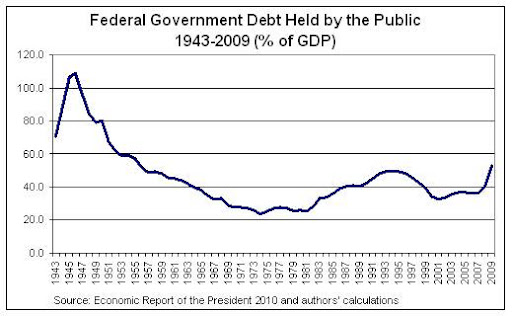

Figure 1 shows federal government debt since 1943.

Note that during WWII the government’s deficit (which reached 25% of GDP) raised the publicly held debt ratio above 100%– much higher than the ratio expected to be achieved by 2015 (just under 73%). Further, in spite of the warnings issued in the Reinhart and Rogoff study, US growth in the postwar period was robust— in fact it was the golden age of US economic growth. Ironically, this is even acknowledged in the report by the IMF’s Lipsky—who noted that the average ratio of government debt to GDP in the advanced countries will reach the postwar 1950 peak of somewhat more than 75%. Again, misfortune did not befall those big government spenders after WWII. Actually, debt ratios came down over the postwar period as relatively robust growth grew the denominator (GDP) relative to the numerator (government debt).

Indeed, robust growth reduces budget deficits by raising tax revenue and reducing certain kinds of government spending such as unemployment compensation. That was exactly the US experience in the postwar period. The budget deficit is highly counter-cyclical, and will come down automatically when the economy recovers.

The claim made by Moody’s that growth will not reduce debt ratios does not square with the facts of historical experience and must rely on the twin assumptions that growth in the future will be sluggish and that government spending will grow relative to GDP. However, such an outcome is inconsistent: if government spending grows fast it raises GDP growth and hence tax revenues, reducing the budget deficit. This is precisely what has happened in the US over the entire postwar period. It is only when government spending lags behind GDP growth by a considerable amount that it slows growth of GDP and tax revenues, causing the budget deficit to grow. What Rogoff and Reinhart do not sufficiently account for is the “reverse causation”: slow growth generates budget deficits. This goes a long way toward explaining the correlation they find between slow growth and deficits: as economists teach, correlation does not prove causation!

Actually, there are always two ways to achieve the same budget deficit ratio: the ugly (Japanese) way and the virtuous way. If fiscal policy remains chronically too tight even in recession, economic growth is destroyed, tax revenues plummet, and a deficit opens up. So far, that is—unfortunately—the US path in this recession, a path already well-worn by two decades of Japanese experiments with belt-tightening. The alternative (let us call it the Chinese example) is that a downturn is met with an aggressive and appropriately-sized discretionary response. In that case, growth is quickly restored, tax revenue begins to grow, and the budget deficit is reduced.

We emphasize that the deficit outcome is of no consequence for a sovereign nation. What is important is that the “ugly” Neoliberal path means chronically insufficient demand, high unemployment, and lots of suffering. The virtuous path—which is always available to a sovereign government—means less loss of output and employment, and relatively rapid resumption of economic growth. So it is not the deficit outcome that matters, rather it is the real suffering imposed by slow growth that results when fiscal policy is too tight.

In conclusion, the Neoliberal agenda would impose the ugly path on the US and UK. President Obama and Prime Minister Brown should tell the Neoliberals to take a hike.