By Yeva Nersisyan and L. Randall Wray

The true effects of government deficits and debt on the economy have been discussed here and here. But these previous posts have not addressed in detail the distinction between domestic and foreign ownership of Treasury debt. In this post we would like to clarify what foreign ownership of treasury securities really means and whether it represents any real dangers for the U.S.

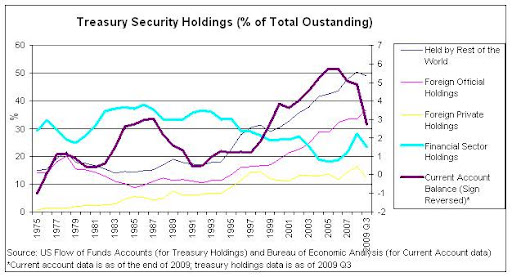

The following figure shows foreign ownership of US federal government debt, by percent of the total publicly held debt. The percent of the total held by foreigners has indeed been climbing—from less than 20% through the mid 1990s to nearly fifty percent today. Most of the growth is by “official” holders—foreign treasuries or central banks, now accounting for more than a third of all publicly held federal debt. This is supposed to represent US government ceding some measure of control over its purse strings to foreign governments.

The heavy purple line shows the US current account balance—largely made up of our trade deficit. (Note the sign is reversed: a deficit is shown as positive; a surplus is negative.) Since 1980 this had fluctuated near a range of minus 1 or 2 percent of GDP. However, after 1999 the current account balance plummeted to a negative 6% of GDP; while it has turned around to some extent during the global downturn, it was still nearly a negative three percent of GDP. Note that the rapid growth of foreign holding of treasuries coincided with the rapid growth of the current account deficit—a point we return to below.

The final (light blue) line plotted above shows domestic financial sector holdings of treasuries. This had been on a downward trend until the current global crisis—when a run to liquidity led financial institutions to increase purchases. Note also that financial sector holdings act as something like a buffer—when foreign demand is strong, US financial institutions reduce their share; when foreign demand is weak, US institutions increase their share. In recent months, the current account deficit has fallen dramatically; this has reduced foreign accumulation of dollar assets—with a small reduction of the percent of treasuries held by foreigners.

Of course, new issues of treasuries have increased with the growing budget deficit, and US financial institution holdings at first increased (the run to liquidity in the crisis). Foreign official holdings have also continued their climb. This could be because the US dollar is still seen as a refuge of safety, but more likely it is because nations still want to accumulate dollar reserves to protect their currencies. That is the other side of the liquidity crisis coin, of course—if there is a fear of a run to liquidity, exchange rates of countries thought to be riskier would face depreciation. Indeed, the graph shows that foreign official holdings of US treasuries began a long term trend in the late 1990s, after the Asian Tiger crisis. The lesson that seems to have been learned by at least some governments is that holding US treasuries offers protection to nations that try to peg their exchange rates.

The next figure displays the top foreign holders of US treasuries. While most public discussion has focused on Chinese holdings, Japanese holdings had been greater than Chinese holdings previous to 2008—and again surpassed those of China as of December 2009. Indeed, Japanese holdings reached nearly forty percent in the mid 2000s—far greater than the Chinese peak holdings. As we discussed above, there is a link between US current account deficits and foreign accumulation of US treasuries. Note also that the most recent data from China indicate that it ran an overall trade deficit; its accumulation of foreign assets must have slowed. It is too early to know whether this will continue—since it probably is due to relatively rapid growth in China in the context of a global recession. If it does, however, Chinese accumulation of US treasuries will probably slow.

Looking at it from the point of view of holders of dollar assets, their current account surpluses allow them to accumulate dollar-denominated assets. In the first instance, a trade surplus leads to dollar reserve credits (cash plus credits to reserve accounts at the Fed); since these balances have until very recently earned no interest they were most often exchanged for US treasuries and other financial assets. Thus, it is not surprising to observe a link among US trade deficits, foreign trade surpluses, and foreign accumulation of US treasuries. To put it concisely: Japan and China are big holders of foreign assets because they are exporters; and as the US is a target for their exports, dollar assets including US treasuries accumulate in Japan and China.

While this is usually presented as foreign “lending” to “finance” the US budget deficit, the correlation between US budget deficits and foreign accumulation of US treasuries does not actually demonstrate causation. The US current account deficit can just as well be taken as the source of foreign current account surpluses that can take the form of accumulations of US treasuries. In fact, by identity, the only way the rest of the world can net export to the US is if it accumulates an equal amount of US financial assets (adjusted by US official transactions). And it is the “propensity” (if not willingness) of the US to simultaneously run trade and government budget deficits that provides the wherewithal for foreign accumulation of treasuries. Obviously there must be a willingness on all sides for this to occur—we could say that it takes (at least) two to tango—and most public discussion ignores the fact that the Chinese desire to run a trade surplus with the US is linked to its desire to accumulate dollar assets. At the same time, the US budget deficit helps to generate domestic income that allows our private sector to consume and invest—some of which fuels imports, providing the income foreigners use to accumulate dollar saving—even as it generates treasuries accumulated by foreigners. So in this case, it takes three to tango.

In other words, the decisions cannot be independent—it makes no sense to talk of Chinese “lending” to the US without also taking account of Chinese desires to net export. Indeed all of the following are linked (possibly in complex ways): the willingness of Chinese to produce for export, the willingness of Chinese to accumulate dollar-denominated assets, the shortfall of Chinese domestic demand that allows China to run a trade surplus, the willingness of Americans to buy foreign products, the high level of US aggregate demand that results in a trade deficit, and the factors that result in a US government budget deficit. And of course it is even more complicated than this because we must bring in other nations as well as global demand taken as a whole.

While it is claimed that the Chinese might suddenly decide they do not want US treasuries any longer, at least one but more likely many of these other relationships would also need to change for that to happen. For example it is often said that China might decide it would rather accumulate Euros. While this could tend to promote more exports to the euro zone, there are complications on the financial side. For example, there is no equivalent to the US treasury in the eurozone. China could accumulate the euro-denominated debt of individual governments—say, Greece!—but these have different risk ratings. And with the sheer volume of Chinese exports, China’s purchases of national government euro debt further increases risk by driving down risk premiums—with China absorbing too much country-specific risk to feel comfortable purchasing individual euro nation debt.

Further, the euro nations, taken as a whole (and this is especially true of its strongest member, Germany) attempts to constrain domestic demand in order to promote exports. In other words, by design, Euroland will not passively allow itself to be a source of net demand for Chinese exports. Therefore if China sold its dollars and bought euros–weakening the dollar and strengthening the euro–it could lose more US exports than it would gain in euro zone exports. China would likely reverse course very quickly. A similar story can be told with respect to an attempt by China to export to Japan—another nation that relies heavily on exports—to accumulate Japanese government debt. And because China does seem to worry about capital losses on its dollar holdings, it would appear to have a low tolerance for dollar depreciation caused by its own actions. In other words, if it caused the euro or yen to rise relative to the dollar, it would quickly change policy to prop up the dollar. For these reasons, we seriously doubt any scenario in which China runs out of the dollar.

We are not arguing that the current situation will go on forever, although we do believe it will persist much longer than most commentators presume, based on our belief that China is intent on supporting its export sector. We are instead pointing out that changes are complex and that there are strong incentives against the sort of simple, abrupt, and dramatic shifts that are posited as likely scenarios. We expect that the complexity as well as the linkages among balance sheets and actions will ensure that transitions are more moderate that many observers currently expect.

Finally, many are concerned with the “interest burden” entailed in foreign ownership of US treasuries: the US is committed to making “costly” interest payments. Referring specifically to China, on an operational level it gets its dollars by selling goods and services to the US. When it gets paid it gets a credit balance in its reserve account at the Fed. Buying Treasury securities entails nothing more than shifting funds in China’s reserve account at the Fed to China’s securities account at the Fed. And when those securities mature, funds are simply shifted back to China’s reserve account at the Fed, with interest also credited to China’s reserve account.

Note that none of these transactions has anything to do with actual government spending, which operationally and independently consists of changing numbers upwards in the accounts of the recipients of government spending—and most of these are domestic residents and firms. The too often invoked imagery of ‘borrowing billions from China to fund health care and the war in Afghanistan and leaving the debt for our children to pay’ is at best an inapplicable absurdity. At worst our children will be simply doing nothing more than debiting and crediting accounts at the Fed just like we do and just like our mothers and fathers did before us. We don’t owe China anything more than a bank statement showing the accounts at the Federal Reserve Bank where their funds are recorded.

Finally, some worry that China might someday present its holdings of reserves and treasuries at the Fed to US exporters, converting its dollar claims to claims on US output. Yes, that could happen. If it does, the demand for US exports will be met by some complexly determined combination of dollar appreciation, rising prices of US exports, and a greater quantity of exports. The later two effects would almost certainly increase US production and hence employment. If there is any burden of Chinese ownership of US dollar assets, it is that US employment and exports to China could be higher. Ironically, most of those who fear US indebtedness to China would actually celebrate these impacts if they were to occur. (They do not understand that imports are a benefit and exports are a cost—but that is a topic we will leave for another day.)

In conclusion, it is time to put the fears about Chinese holdings of US treasuries to rest.