In Neoclassical theory, money is really added as an after thought to a model that is based on a barter paradigm. In the long run, at least, money is neutral, playing no role except to determine unimportant nominal prices. Money is taken to be an exogenous variable-whose quantity is determined either by the supply of a scarce commodity (for example, gold), or by the government in the case of a “fiat” money. In the money and banking textbooks, the central bank controls the money supply through its provision of required reserves, to which a deposit multiplier is applied to determine the quantity of privately-supplied bank deposits.

The evolving Post Keynesian endogenous approach to money offers a clear alternative to the orthodox, neoclassical approach. With regard to monetary theory, early Post Keynesian work emphasized the role played by uncertainty and was generally most concerned with money hoards held to reduce “disquietude”, rather than with money “on the wing” (the relation between money and spending). However, Post Keynesians always recognized the important role played by money in the “monetary theory of production” that Keynes adopted from Marx. Circuit theory, mostly developed in France, provided a nice counterpoint to early Post Keynesian preoccupation with money hoards, focusing on the role money plays in financing spending. The next major development came in the 1970s, with Basil Moore’s horizontalism (somewhat anticipated by Kaldor), which emphasized that central banks cannot control bank reserves in a discretionary manner. Reserves must be “horizontal”, supplied on demand at the overnight bank rate (or fed funds rate) administered by the central bank. This also turns the textbook deposit multiplier on its head as causation must run from loans to deposits and then to reserves.

This led directly to development of the “endogenous money” approach that was already apparent in the Circuit literature. When the demand for loans increases, banks normally make more loans and create more banking deposits, without worrying about the quantity of reserves on hand. Privately created credit money can thus be thought of as a horizontal “leveraging” of reserves (or, better, High Powered Money), although there is no fixed leverage ratio. In recent years, some Post Keynesians have returned to Keynes’s Treatise and the State Theory of Money advanced by Knapp and adopted by Keynes therein. Rather than imagining a barter economy that discovers a lubricating medium of exchange, this neo-Chartalist approach emphasizes the role played by the state in designating the unit of account, and in naming exactly what thing answers to that description. Taxes (or any other monetary obligations imposed by authorities) then generate a demand for that money thing. In this way, Post Keynesians need not fall into the “free market” approach of orthodoxy, which imagines some pre-existing monetized utopia free from the evil hands of government. The neo-Chartalist approach also leads quite nicely to Abba Lerner’s functional finance approach, which refuses to make a fine separation of fiscal from monetary policy. Money, government spending, and taxes are thus intricately interrelated. This approach rejects Mundell’s “optimal currency area” as well as the monetary approach to the balance of payments. It is not possible to separate fiscal policy from currency sovereignty-which explains why the “one nation, one currency” rule is so rarely violated, and when it is violated it typically leads to disaster (as in the current case of Argentina, and-perhaps-in the future case of the European Union!).

Like Keynes, Post Keynesians have long emphasized that unemployment in capitalist economies has to do with the fact that these are monetary economies. Keynes had argued that the “fetish” for liquidity (the desire to hoard) causes unemployment because it keeps the relevant interest rates at too high a level to permit sufficient investment to raise aggregate demand to the full employment level. While it would appear that monetary policy could eliminate unemployment either by reducing overnight interest rates, or by expanding the quantity of reserves, neither avenue will actually work. When liquidity preference is high, there may be no rate of interest that will induce investment in illiquid capital-and even if the overnight interest rate falls, this does not mean that the long term rate will. Further, as the horizontalists make clear, the central bank cannot simply increase reserves in a discretionary manner as this would only result in excess reserve holdings and push the overnight interest rate to zero without actually increasing the money supply. Indeed, when liquidity preference is high, the demand for, as well as the supply of, loans collapses. Hence, there is no way for the central bank to simply “increase the supply of money” to raise aggregate demand. This is why those who adopt the endogenous money approach reject ISLM-type analysis in which the authorities can eliminate recession simply by expanding the money supply and shifting the LM curve out.

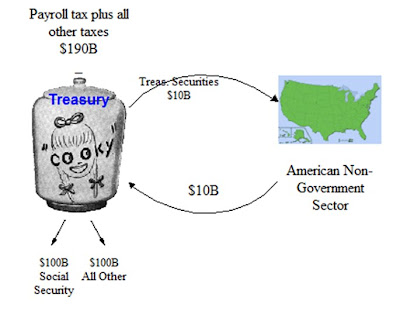

Furthermore, unlike orthodox economists, Post Keynesians reject a simple NAIRU or Phillips Curve trade-off according to which some unemployment must be accepted as “natural” or as the cost of fighting inflation. Earlier, some Post Keynesians had argued for “incomes policy” as an alternative way of fighting inflation, however, that rarely proved to be politically feasible. Lately, at least some Post Keynesians have argued that not only is the inflation-unemployment “trade-off” unnecessary, but that full employment can be a complement to enhanced price stability. This is accomplished through creation of a “buffer stock” of labor, according to which the government offers to hire anyone ready, willing, and able to work at some pre-announced and fixed wage. The size of the buffer stock moves counter-cyclically, such that government spending on the program will act as an “automatic stabilizer”. At the same time, the fixed wage and benefit package helps to moderate fluctuation of “market” wages. Finally, it is emphasized that the “functional finance” approach to money and fiscal policy advanced by Lerner explains why any nation that operates with a sovereign currency will be able to “afford” full employment. In this way, it is recognized that while unemployment exists only in monetary economies, unemployment does not have to be tolerated even in monetary economies. When aggregate demand is low, fiscal policy-not monetary policy-can raise demand and provide the needed jobs. The problem is not that money is “neutral”, but that when demand is low, the private sector will not create money endogenously, hence, the government must expand the supply of HPM through fiscal policy. If a deficit results, this will increase reserves held by the banking system, which must be drained through sale of government bonds in order to prevent a situation of excess reserve holdings from pushing overnight interest rates to zero. Therefore, bond sales by the treasury are seen as an “interest rate maintenance operation” and not as a “borrowing” operation. Indeed, no sovereign issuer of the currency needs to borrow its own currency from its population in order to spend.

——————————————————————————–

FOR FURTHER READING

Brunner, Karl. 1968. “The Role of Money and Monetary Policy”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, vol 50, no. 7, July, p. 9.

Cook, R.M. 1958. “Speculation on the Origins of Coinage”, Historia, 7, pp. 257-62.

Davidson, Paul. Money and the Real World, London, Macmillan, 1978.

Deleplace, Ghislain and Edward J. Nell, editors. Money in Motion: the Post Keynesian and Circulation Approaches, New York, St. Martin’s Press, Inc., 1996.

Dow, Alexander and Schiela C. Dow 1989. “Endogenous Money Creation and Idle Balances”, in Pheby, John, ed, New Directions in Post Keynesian Economics, Aldershot, Edward Elgar, p. 147.

Friedman, Milton. 1969. The Optimal Quantity of Money and Other Essays, Aldine, Chicago.

Grierson, Philip (1979), Dark Age Numismatics, Variorum Reprints, London.

—–. 1977. The Origins of Money, London: Athlone Press.

Hahn, F. 1983. Money and Inflation, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Innes, A. M. 1913, “What is Money?“, Banking Law Journal, May p. 377-408.

Kaldor, N. The Scourge of Monetarism, London, Oxford University Press, 1985.

Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory, New York, Harcourt-Brace-Jovanovich, 1964.

—–. A Treatise on Money: Volume 1: The Pure Theory of Money, New York, Harcourt-Brace-Jovanovich, 1976 [1930].

Knapp, Georg Friedrich. The State Theory of Money, Clifton, Augustus M. Kelley 1973 [1924].

Lerner, Abba P. “Money as a Creature of the State”, American Economic Review, vol. 37, no. 2, May 1947, pp. 312-317.

Marx, Karl. Capital, Volume III, Chicago, Charles H. Kerr and Company, 1909.

Moore, Basil. Horizontalists and Verticalists: The Macroeconomics of Credit Money, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Mosler, Warren, Soft Currency Economics, third edition, 1995.

Parguez, Alain.1996. “Beyond Scarcity: A Reappraisal of the Theory of the Monetary Circuit”, in E. nell and G. Deleplace (eds) Money in Motion: The Post-Keynesian and Circulation Approaches, London: Macmillan.

Rousseas, Stephen. Post Keynesian Monetary Economics, Armonk, New York, M.E. Sharpe, 1986.

Wray, L. Randall. Understanding Modern Money: The Key to Full Employment and Price Stability, Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, 1998.

—–. Money and Credit in Capitalist Economies: The Endogenous Money Approach, Aldershot, Edward Elgar, 1990.