By Marilynne Meikenhous*

The debate surrounding the nature of money is an impassioned one. Our understanding of money and the policy implementation based on our beliefs differ momentously. Have our policies reflected a true understanding of how money functions in a modern society, and have these policies worked? In order to answer this, it is first necessary to explore what money is. This typically depends on how you think money came into existence, what money is used for, and how money functions in the modern economy. The way that one incorporates money into a discussion of macroeconomics is arguably what indicates their economic background and beliefs.

Part 1: Orthodoxy

There are two major features of orthodox theory that are in direct opposition to any heterodox theory. One feature is that money is ‘commodity money’, or further that money is (and functions as) a commodity itself. The second feature that sets orthodox theory apart from heterodox theory is that money is considered neutral, or even super-neutral. Both of these theories will be explored in detail. First, orthodox followers believe money is neutral and that it has no effect on real economic variables. The orthodox framework holds money in relation to exchange, this is commonly referred to as a C-M-C’ economy where money (M) is used as a way to make barter easier. Pavlina Tcherneva (2005) writes in her working paper, The Nature, Origins, and Role of Money: Broad and Specific Propositions and Their Implications for Policy, “The standard story deems money to be neutral – a veil, a simple medium of exchange, which lubricates markets and derives its value from its metallic content” (pg. 2). This assumes that the “value” of money is embodied in the money itself. Also implied is that the use of money is simply to make exchange easier, eliminating the ‘coincidence of wants’ problem. Tcherneva (2005) goes on to write, “money spontaneously emerges as a medium of exchange from the attempts of enterprising individuals to minimize the transaction costs of barter” (pg. 2). Followers of this view include schools of thought such as classical/neoclassical schools, and monetarists (although monetarists recognize some short run significance as will be explained later). These schools of thought assign little to no role for money in affecting the economy. A change in the money supply (according to most orthodox schools) only leads to changes in the short-run price level, with no effect on other real economic variables. John Smithin (2003) asserts, “A substantial proportion of economic theory and thinking about economic policy actually assigns no role to money, or at least a very minor role, in the determination of the ‘real’ economic variables that are thought to be of primary interest” (Controversies in Monetary Economics, pg. 1). This belief is based on the orthodox story of how money came to be.

Orthodox economists believe that the primary function of money is to make exchange of goods and services easier. The orthodox story about what money is evolves from their story about how money came to be. They believe that our primitive ancestors would make a commodity and would trade that commodity for some other commodity that they needed and couldn’t produce themselves. The problems they faced were ease of portability of commodities, coincidence of wants and difficulty in creating commodity denominations. Because of this, our ancestors decided to use some object that was readily acceptable by others to be a medium of exchange. So long as people would continue to accept money in exchange for commodities, the barter economy would thrive and people could buy what they need. This is commonly referred to a C-M-C’ economy where commodities (C) first drove the need for the creation of money (M) in order to purchase other commodities (C’), the goal being to acquire more commodities or different commodities than you started with. This however, does not represent an understanding of the origins and function of money (which will be discussed in more detail later) as there is no evidence of market systems based on barter.

What follows is the orthodox view of money being a store of value in itself. According to Smithin (2003), “From this point of view, the role of money as a store of value would actually follow from that of the medium of exchange” (pg. 20). Followers of the orthodox school believe that the value of the money is based on the price of gold, that is, the value of the money is embodied in the money itself. Gold was especially attractive as money because since there was a demand for it in the form of jewelry and other things, it was not only valued based on its role as a medium of exchange, but it had value itself as a coveted commodity. Mitchell Innes (1913) describes the intended function of metal money when he writes, “a certain fixed weight of one of these metals of a known fineness became a standard of value, and to guarantee this weight and quality it became incumbent on governments to issue pieces of metal stamped with their peculiar sign, the forging of which was punishable with severe penalties” (pg. 377). Gold (or other precious metals) as money presents some problems. First, because gold coinage is easily divisible, it is easy for people to chip off parts of the coin and spend the lighter coin. Because of this, when money returns to the sovereign to be minted again, the sovereign has a shrunken money supply. Marx (1867) writes, “In the course of circulation, coins wear down, some to a greater extent, some to a lesser. The denomination of the gold and its substance, the nominal content and the real content, begin to move apart. Coins of the same denomination become different in value, because they are different in weight” (Capital Volume 1, p. 222). Another problem with precious metals being used as money is that robberies became frequent occurrences. The story that followed explained the origins of modern paper money and is called the “Goldsmith-Bank” story. In this story, gold or other precious metals became money because they are attractive to the eye, easily divisible, and portable. Because of this, Goldsmith-Bankers stored the valuable metals in vaults and issued paper notes backed by the balances in their vaults. This inherently unprofitable venture was made profitable because the bankers assumed that holders of the accounts would not demand all of their money at once, giving the Goldsmith bankers the ability to make interest bearing loans off of their reserves. Money soon became any ‘money thing’ used to make exchange easier that was backed by some real asset or commodity that itself had value. The popularity of bank notes led to the adoption of paper notes issued by the government as the standard money thing.

The function of money according to the orthodox view follows closely with how it is defined. For orthodox economists, since money is super neutral, its function is no other than a unit of account, a way to make exchange easier and a store of value. Some Orthodox economists, however, differ in their view of what money is used for. Monetarists, most commonly Friedman, believed money was not neutral in the short run and changes in the money supply could cause drastic changes in the economy (as we will explore in more detail later). Friedman believed money was only neutral in the long run. He, as well as most neoclassical and classical economists relied heavily on the quantity theory of money MV=PY. He believed that changes in the money supply can and do create huge changes in prices. However, since these changes were not important in the long run, his view was still in line with that of typical orthodoxy. Smithin (2003) writes, “once society possesses the concept of money, changes in the number of units of the item or items designated as money can have no permanent impact on the level of real activity…. Money is therefore at once very important and yet unimportant” (pg. 20). Friedman and his fellow monetarists also assumed adaptive and rational expectations. In general, they assume economic agents form their expectations of the future based off of backward-looking past events. These expectations are assumed to be rational and involve errors that are random and uncommon.

For orthodox economists, money is exogenously determined. According to Meghnad Desai (1989), “those who plug for the exogeneity view take one or all among the cluster of variables price level, interest rate, or real output- as being determined by movements in the stock of money” (The New Palgrave: Money, pg. 146). This assumption follows closely with monetarist views. Exogeneity is not only an issue of ‘where’ money is defined, but also an issue about whether money affects other economic variables, in other words, it is about causality. According to Desai (1989), “as our understanding of the underlying statistical theory concerning causality and exogeneity has advanced in recent years, it must also be added that participants in the controversy conflate the exogeneity of a variable (especially of money) with its controllability by policy” (pg. 146). Given our understanding of the orthodox nature of money, we can easily describe orthodox policy implications that should follow.

Orthodox policy implications have changed and evolved since Adam Smith. To see the evolution, we will begin with Say’s Law. The strong version of Say’s Law suggests that supply creates its own demand. More specifically it, “implies an equality of aggregate demand and supply which is consistent with labor market equilibrium, it is equivalent to the proposition that there is no obstacle to the achievement of full employment in terms of a deficiency of aggregate demand” (Snowdon & Vane, 2005, Modern Macroeconomics: It’s Origins, Developments, and Current State). This theory suggests that no intermediation is necessary in order to influence the economy. Markets in this framework are self-regulating and always adjust back to equilibrium. Newer orthodox theories tell similar stories, but in a slightly different manner leaving some room for intermediation.

Monetarists believe that, in the short-run, changes in the money supply have a drastic effect on prices, but in the long run, wages adjust. They believe the long-run Phillips curve is vertical, which implies that an increased rate of growth of the money supply (a stock) can reduce unemployment below a “natural rate” because of expectations of inflation. Snowdon & Vane (2005) write, “as soon as inflation is fully anticipated, it will be incorporated into wage bargains and unemployment will return to its natural rate” (p. 180). The theory suggests a self-regulating economy where some sort of “natural unemployment” level is the norm and must exist. Monetarists believe that fine-tuning the economy through monetary policy is generally bad policy making, although they do make certain exceptions. In their theory, like classical theory, they assume people are able to obtain perfect information and make their decisions about wage contracts accordingly. For Monetarists, there is some role for policy making. Snowdon & Vane (2005) continue, “the authorities should follow some rule for monetary aggregates to ensure long-term price stability, with fiscal policy assigned to its traditional roles of influencing the distribution of wealth, and the allocation of resources” (p. 193).

Part 2: Heterodoxy

Heterodox views of money vary, but for most schools, money is not neutral. In this section, I will focus heavily on Modern Money Theory as an explanation for the heterodox outlook on money, as well as Ingham, Marx and Keynes. Money is, according to heterodox views, a state monopoly, a social until of measurement, a state money of account, a representation of social value, and actual money things (like paper IOU’s) etc. It is not the fiat money orthodoxy as claimed it to be, but a record of debt with a promise to redeem by the sovereign in payment of taxes, fines, and fees that they issue. The heterodox story of the origins of money differs greatly from the orthodox story. The most commonly cited story is the “Justice, Wergeld, Penal” story.

In this story, a fine/fee/tax of some sort is imposed on a population in compensation for causing injuries and damage in a tribal society. These fees/fines/taxes were used in place of allowing blood feuds. The need to acquire money is based on the necessity to pay the fine/fee/tax to the controlling issuing authority. The heterodox alternative to the nature of money is more involved than just this. First, the heterodox story seeks to explain the origins of money, whether it be through the Wergeld story or something similar, then it identifies the social nature of the money unit of account in which credits and debits are measured, and the social processes which generate creditors and debtors. Heterodox theory recognizes the store of value function of money in that money stores wealth in the form of others’ debts. The most crucial separation occurs in regard to money being a medium of exchange. This is mostly because exchanges can and do take place without a monetary medium of exchange through credits and debits. Ingham (2004) recognizes that the historical and logical foundation of money is not based on some natural emergence to lubricate trade. Ingham (2004) writes in The Nature of Money, “The paucity of the archeological record poses difficulties, but the evidence does not lend support to orthodoxy’s theory of the transition from barter to money” (p. 89). He goes on to explain how money evolved first as debt or unit of account, although he separates these into two stories. First he talks about money evolving as some sort of debt or sacrifice. Ingham (2004) writes, “The primordial debt is that owed by the living to the continuity and durability of the society that secures their individual existence” (p. 90). He goes on to explain how it was a sacrifice in order to appease deities. He explains how “debt” is synonymous with “sin” or “guilt” illustrating the linkage between payment systems and religious obligation. Even in the Christian bible the tax collector is not to be treated unkindly, rather he is to be loved as one should love all. The second story, “locates the use of money of account in the need to calculate economic equivalencies of goods in the agrarian command economies of the ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian empires” (Ingham, 2004, p. 91). In this story, hospitality and redistribution of some sort of a surplus drove the need for a tax/fee/fine. Ingham (2004) continues, “Political, economic and ideological control was centralized and exercised through the money of account” (p. 93). Marx also recognized the origins of money as more than a way to simplify trade.

Although Marx is commonly considered a classicalist, a number of his theories correlate closely with heterodox views. Marx (1867) develops his M-C-M’ theory in Capital Vol. 1. He opens his argument by analyzing the commodity and its use in exchange. He begins by reiterating the same story recited by most classicalists of a C-M-C’ system where the commodity is exchanged for money which is exchanged for a different commodity. Marx (1867) writes, “The cycle C-M-C reaches its conclusion when the money brought in by the sale of one commodity is withdrawn again by the purchase of another” (p. 250). With further development of his theory, Marx (1867) discovers that the end goal is actually money itself, not commodities. He believes the C-M-C form of the process is an incomplete circuit. He writes, “The complete form of this process is therefore M-C-M’” (1867, p. 251). He believes the C-M-C portion vanishes in the final M-C-M’ stage of the circuit. He continues, “Money therefore forms the starting-point and the conclusion of every valorization process” (1867, p. 255). This story is one of many in direct opposition to the orthodox story of how money came to be. Although Marx explores the difference between a C-M-C and an M-C-M’ economy, he does not go into detail as to how a modern society becomes monetized from a heterodox point of view.

Keynes[1] also recognized the importance of money and its role in the economy. In Chapter 13 of The General Theory, Keynes (1936) lays the foundations for modern heterodox views on money. First, Keynes believed that money (more importantly interest rates on money) did have a real effect on economic variables. He believed that interest was the payment one received for becoming illiquid. Keynes (1936) writes, “the mere definition of the rate of interest tells us in so many words that the rate of interest is the reward for parting with liquidity for a specific period” (p. 167). He made it clear that the interest rate is not price, “which brings into equilibrium the demand for resources to invest with the readiness to abstain from present consumption. It is the “price” which equilibrates the desire to hold wealth in the form of cash with the available quantity of cash.” (p. 167). However, Keynes wanted to make sure that it was clear that money does not act in a predictable way and that the economy tends to be volatile. He very famously writes, “If, however, we are tempted to assert that money is the drink which stimulates the system to activity, we must remind ourselves that there may be several slips between the cup and the lip” (p. 173). Keynes believes that in most circumstances, the lowering of interest rates stimulates investment, which he held as the most volatile economic variable. In this way money, through the mechanism of the interest rate, has a direct impact on real economic variables.

Modern Money Theorists believe taxes drive money. In MMT, one of the most important functions of a sovereign government is their ability to levy and collect taxes in the national money of account. Where Modern Money theorists recognize that government currency can be used for other purposes such as savings, purchases, and debt elimination, they assert that these functions are secondary functions of money. Wray (2012) writes, “these other uses of currency are all subsidiary, deriving from government’s willingness to accept its currency in tax payments” (Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems, p. 49). In MMT, the government or issuing authority has to first create money and distribute it. Money does not have to be “backed” by any metal or legal tender law. Wray (2012) continues, “It is not necessary to “back” the currency with precious metal, nor is it necessary to enforce legal tender laws that require acceptance of the national currency” (p. 50). Money is only “backed” by the promise that you can pay your taxes with it and that you can buy another unit of currency in the same denomination from the sovereign. The purpose and end goal of money is to bring resources to the public sector. Our understanding of the nature and function of money has great implications on policy decisions.

First, it is necessary to understand the benefits of a sovereign currency and the effects of a floating exchange rate regime in order to understand what policy implications should follow. According to MMT, the exchange rate regime that provides the greatest independence for domestic policy is a floating exchange rate regime. This assumes a sovereign domestic currency where the issuer of the currency has a monopoly on the supply of the currency. In an economy with a floating exchange rate system, the “value” of the currency fluctuates based on demand for the currency (or goods sold in the currency) from the rest of the world. A “strong” currency verses a “weak” currency only shows a preference for importing or exporting. A country who values exports would prefer to keep their currency ‘weak’ allowing their goods to be cheaper to the rest of the world. A country who values a ‘strong’ currency values importing. Our currency is ‘strong’ because there is a general worldwide demand for dollars, as it is considered a world reserve currency.

Secondly, (and most importantly) a government with a sovereign currency can afford to “buy back” all of the dollars that exist in the rest of the world. In an economy where a floating currency is the system, a government does not need to act as a household would. The government is the sovereign issuer of the currency and spends by crediting accounts with “keystrokes” and taxes the same way. A sovereign nation does not need to borrow money to finance debt or to spend, as it is not a household with normal household budget constraints.

A government issues a tax, fine, fee etc. and creates demand for its currency. This means financial constraints are self-imposed and the government can afford to pay off all of its debts. One of the most important aspects of a floating currency is that a government with a floating currency is able to “buy anything for sale in [its domestic currency] simply through “keystrokes”. And it does not need to “borrow” its own currency” (Wray, 2012, p. 167). This property in itself has serious implications.

According to MMT, fiscal operations are the most important policy functions in a country. When a country has a floating exchange rate, it has a lot of space for fiscal (and monetary) policy. A benefit of a floating exchange rate is that budget deficits are not a problem, and these deficits can’t burden the economy since the issuer of a sovereign currency can afford to pay all of its debts if they are denominated in its currency. Also, budget deficits and government debt means savings in other parts of the economy. In short, the only way a country can protect itself from continuous economic downturns is to adopt a floating exchange rate regime with a sovereign currency.

With the understanding of how modern money works, it becomes apparent that any budgetary restrictions are self-imposed and based on a belief that the government runs like a household. There is a basic accounting identity as outlined in Wray’s book, Modern Money Theory (2012), “It is a fundamental principle of accounting that for every financial asset there is an equal and offsetting financial liability” (p. 1). Here, he emphasizes that one’s financial asset is another’s financial liability. To see how this works, the economy can be broken into three sectors; the private domestic sector, the public domestic sector, and the rest of the world. Via a ‘zero-sum game’, not all three sectors can be in surplus or deficit at the same time, this is simply an accounting identity. So, for example, if our net exports are negative and the private sector is in surplus, by identity, our public sector must also be in deficit, this is the only way the private surplus is sustainable with negative net-exports. Any deficit spending is not discretionary, only the ‘budget’ which made the spending ‘deficit spending’ is. When we think of the basic three-sector accounting identity as presented in Modern Money Theory (2012) it brings to light an astonishing truth. First, if policymakers knew the function of money and understood its potential role in the economy, there would no longer be a push to stop deficit spending. It is a natural automatic stabilizer in times of recession. Also, it would be understood that public sector debt means private sector surplus. This is simply an accounting identity. Unemployment, therefore, is always the fault of the public sector and the ONLY problem the government faces is full employment of resources and inflation. All other constraints are political and self-imposed.

With these basic understandings, it becomes apparent that there is no issue of insolvency or debt default unless it is self-made. The implications of this are that we do not have “fiat” money, and money is an important economic factor with real economic outcomes. All money is credit money, where the state guarantees to accept it in payment for state debts. So long as a country is the monopolistic creator of a sovereign currency, they will always be able to pay off all debts, employ all people seeking employment, and purchase all inventories. Lerner (1947) writes, “Up till now governments have shirked these responsibilities, seeking refuge in an alibi of helplessness. The extraordinary complacency both of the government and of its critics in the face of the recent rise in prices can be appreciated only if one imagines what would have been the reaction to a government declaration that it was going to default on say 30 per cent of its interest and repayments to holders of war bonds and other government obligations” (Money as a Creature of the State, p. 314). When one understands that money is a creature of the state, (that is that it is created by the state and driven by taxes, fines, fees etc. to spur economic growth) there are certain policy recommendations that could be made in order to avoid collapse of the economic system.

Currently, the private sector (firms) is sitting on piles of cash, unwilling to spend it. A policy implication that could be adopted given the nature and function of money is an employer of last resort policy (ELR). The government acting as an ELR would allow an increase in demand through a job guarantee program, and a redistribution of the billions that the private sector is sitting on. According to Abba Lerner (1943), “there is no task facing society today so important as the elimination of economic insecurity” (Functional Finance and the Federal Debt, p. 38). To illustrate this, Abba Lerner’s (1943) “Functional Finance” approach to monetary and fiscal policy has two main principles. First, he believes if domestic income is too low, the government should intervene by spending more (relative to taxes) and that unemployment is an indication of this condition. Secondly, Lerner (1943) suggests a stabilization of the interest rate which must be provided by the government in the form of bank reserves (if the interest rate is too high). Lerner (1943) believes that taxes and bonds do not finance government spending and that taxes act to create a demand for government currency. According to Lerner (1947), “The modern state can make any-thing it chooses generally acceptable as money and thus establish its value quite apart from any connection, even of the most formal kind, with gold or with backing of any kind” (Money as a Creature of the State, p. 313). He believes as the creator of the currency, governments have certain responsibilities, which he calls functional finance. He writes,

“Depression occurs only if the amount of money spent is insufficient. Inflation occurs only if the amount of money spent is excessive. The government-which is what the state means in practice-by virtue of its power to create or destroy money by fiat and its power to take money away from people by taxation, is in a position to keep the rate of spending in the economy at the level required to fill its two great responsibilities, the prevention of depression, and the maintenance of the value of money” (1947, p. 314).

He believes that the government takes an important role in helping to spur economic activity. He believes that the government should be the employer of last resort with a goal of avoiding economic depressions and creating a generally healthy economy. Since the economy is not self-regulating (like orthodox theory suggests) it is important for the government to step in when needed. Since money is a “creature of the state”, the government must take an active role in managing it. He continues, “The key points here are not in the direct supply of money, or even in the regulation of the level of spending. The key points are in the determination of wage rates and in the determination of rates of markup of selling prices over costs” (1947, pg. 315).

Part 3: Common misunderstandings and implications

In the United States, we have been trying to dig ourselves out of the worst financial collapse we have seen since the Great Depression for almost seven years. The federal debt and budget deficits parade the minds of the average American leaving them to believe these phenomena are contributing to our slow recovery. I argue that our response to these phenomena perpetuate our problem. Many Americans believe we are going bankrupt, we will lose social welfare programs that take care of our poor and elderly citizens, and that we will burden our future generations with a tremendous load of debt which will be inescapable. Most of these misguided ideas come to the American public in the form of ‘fire and brimstone’ news from an ill-informed media and political leaders. Here, I will address some of the common misconceptions, truths behind these misconceptions, and the damage our policy makers have done by proliferating their bad information.

First, it is a common misconception that a government must tax or borrow to finance spending. This is probably one of the leading misconceptions causing the American public to cringe over deficit spending and the federal debt. As noted previously, if a country is the monopoly issuer of a currency, default is not an option and the federal government does not operate like a household. In The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy, Warren Mosler (2010) writes, “Federal government spending is in no case operationally constrained by revenues, meaning that there is no “solvency risk.” In other words, the federal government can always make any and all payments in its own currency, no matter how large the deficit is, or how few taxes it collects” (p. 13). Another implication of this is that Social Security, Medicaid, Medicare, and every other social welfare program is not at risk of losing funding unless it is self-imposed politically. Another common misconception is that deficit spending and debt will be left to future generations, causing a decline in future consumption and output. With a sovereign currency, this simply isn’t the case. Our children will face the same identities and constraints facing us today. Mosler (2010) continues, “Collectively, in real terms, there is no such burden possible. Debt or no debt, our children get to consume whatever they can produce” (p. 31). This also includes what they can net import. Again, any constraints are self-imposed and this assumption forms from the belief that we will have to ‘finance’ our spending somehow, which is not how a country with a sovereign currency works.

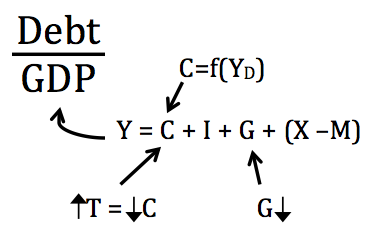

Without a basic understanding of monetary functions in a sovereign country, policies are often misguided. Our policymakers seem to be overly focused on how to lower our debt-to-GDP ratio in an attempt to avoid many of the problems that they believe are associated with deficit spending and a federal debt. As previously mentioned, public deficits drive private savings and public debt isn’t destabilizing. Some policy makers have pushed for decreasing government spending and raising taxes in an attempt to ‘fix’ our ‘problem’. As I will illustrate, an increase in taxes only leads to less consumption spending and a decrease in government spending only leads to a potential decline in GDP, furthering our ‘problem’. The following was presented by Dr. Kelton during the spring semester of 2013 in her International Finance class:

This shows that consumption is a function of disposable income and when taxes are increased, it causes lowers consumption. When the lowering of consumption is added to the decrease in government spending, the denominator of the ratio decreases, causing the debt-to-GDP ratio to actually rise, contributing to the ‘problem’ these policy makers wish to avoid. The IMF published a report in January of 2013 explaining that their previous beliefs associated with fiscal consolidation (that is, increasing revenues and lowering government spending) incorrectly estimated growth outcomes. Olivier Blanchard (2013) looked at the effect of multipliers related to fiscal consolidation and with further review, found the original IMF findings were incorrect. Blanchard (2013) writes, “when we decompose the effect on GDP in this way, we find that planned fiscal consolidation is associated with significantly lower-than-expected consumption and investment growth” (p. 18). Blanchard (2013) also noted, “We find that a 1 percentage point of GDP rise in the fiscal consolidation forecast for 2010-11 was associated with a real GDP loss during 2010-11 of about 1 percent, relative to forecast” (p.4). These findings align with the theory previously illustrated. Deficit spending and government intervention through expansionary fiscal policy have been the only actions proven to lift an economy out of recession. Until policymakers on both sides acquire a basic understanding of how money functions, our policies will continue to fail.

*A Note:

For the next few weeks we will be running a series of articles on monetary theory and policy. These are final essays written by MA students in my class this past Fall semester. I was very happy with the results—students indicated that they had a firm grasp of both the orthodox approach as well as the heterodox approach to the subject. Most of them also included some Modern Money Theory in their answers. I asked about half of the students in the class if they would like to contribute their essay to this series. Sometimes students are the best teachers because they see things with a fresh eye and cut to what is important. They are usually less concerned with esoteric academic debates than are their professors. Note that these contributions are voluntary and are written by Masters students. I told students they could choose to use their own names, or they could choose an alias. Comments are welcome, but please be nice—remember these are students.

For your reference, here were the topics for the paper. The paper had a maximum limit of 6000 words.

Choose one of the following. You must consider and address both the orthodox approach and the heterodox approach in your essay. Where relevant, include various strands of each.

A) What is the nature of money? Given the nature of money, what approach should be taken to policy-making?

B) What is the nature of banking? Given the nature of banking, what approach should be taken to policy-making?

C) According to John Smithin there are several main themes throughout controversies of monetary economics, each typically addressed by each of the various approaches to monetary theory and policy. In your essay, discuss how each of the approaches we covered this semester tackles these themes enumerated by Smithin.

L. Randall Wray

References

Blanchard, O. & Leigh, D. “Growth Forecast Errors and Fiscal Multipliers”. International Monetary Fund: January.WP/13/1

Desai, M. (1989). “Endogenous and Exogenous Money”. The New Palgrave: Money. The Macmillan Press Ltd.

Ingham, G. (2004). The Nature of Money. Cambridge: Polity Press Ltd.

Innes, A.M. (1913,1914). “What is Money?” Banking Law Journal. May: 337-408. Reprinted in L.R. Wray (ed.), Credit and State Theories of Money, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar (2004), pp. 14-49.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Cambridge: Palgrave Macmillian.

Lerner, A.P. (1943), “Functional Finance and the Federal Debt.” Social Research vol. 10, 38-51

Lerner, A.P. (1947), “Money as a Creature of the State”, American Economic Review, 37 (2), May, 312-17

Marx, K. (1867). Capital Volume 1. Published 1976. London: Penguin Books Ltd

Mosler, W. (2010). The Seven Deadly Frauds of Economic Policy. Valance Co. Retrieved online http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf

Smithin, J. (2003). Controversies in Monetary Economics-revised ed. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Snowdon, B & Vane H.R. (2005). Modern Macroeconomics: Its Origins, Development, and Current State. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

Tcherneva, P. (2005). “The Nature, Origins, and Role of Money: Broad and Specific Propositions and Their Implications for Policy”, University of Missouri- Kansas City, Available from the Levy Institute. (Working paper No. 46. )Retrieved from http://levy.org

Wray, L. R. (2012). Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems. Palgrave Macmillian.

[1] I would like to note that when I am referring to Keynes, I am referring to his theories outlined in The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936). I am not referring to IS-LM theorists.

Pingback: Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: on the Nature of Money Pt. 7 - EXPOSING BLACK TRUTH