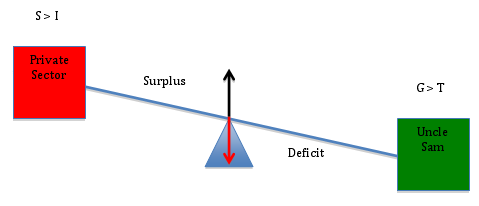

In a recent post, I used a simple teeter-totter diagram to show how the government’s financial balance is related to the private sector’s financial balance in a closed economy. With only two sectors – government and non-government – I showed that a government deficit necessarily implies a surplus in the private sector.

As expected, this accounting truism ruffled the feathers of a flock of readers who have been programmed to launch into an anti-government tirade at the mere mention of the public sector and to regard the dangers of deficit spending as an unimpeachable fact. And while you’re certainly entitled to your own political views, you are not, as Senator Moynihan famously said, entitled to your own facts.

Other, less impenetrable minds, agreed that the private sector’s financial position must improve as the government’s deficit increases in a closed economy, but they argued that I had not demonstrated anything meaningful because I ignored the financial flows that occur in an open economy.

I still hope to convince both groups that they are acting against their own economic interests when they support policies to balance the budget or reduce the deficit, either by raising taxes or cutting government expenditures. So let’s continue the exercise and, as promised, extend the argument to the more realistic open-economy in which we actually live.

In an open economy, income flows into and out of the domestic economy as residents and foreigners buy goods and services (exports minus imports), make and receive payments such as interest and dividends (factor income) and make net transfer payments (such as foreign aid). Each country keeps track of these payments using a balance of payments (BOP) account, which summarizes the international monetary transactions that take place between the home country and the rest of the world. The BOP has two primary components – the current account and the capital account – and we can use either one to show whether, on balance, money is flowing into or out of a country.

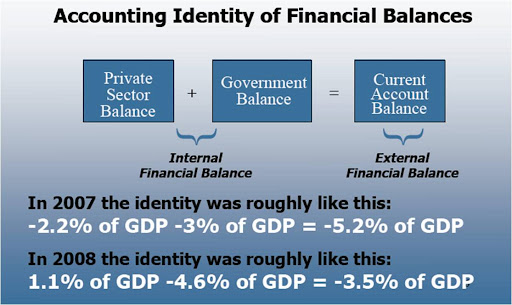

When we incorporate these international flows, we transform the closed-economy accounting identity I used in my previous post:

[1] Domestic Private Surplus = Government Deficit

into the open-economy accounting identity shown below:

[2] Domestic Private = Government + Current Account

Surplus Deficit Balance

or, equivalently,

[3] Domestic Private = Government + Capital Account

Surplus Surplus Balance

When the current account balance is positive, it means that we in the private sector (households and domestic firms) are accumulating net financial claims on foreigners. When it is negative, they are accumulating net financial claims on us. Thus, a positive current account implies a negative capital account and vice versa.

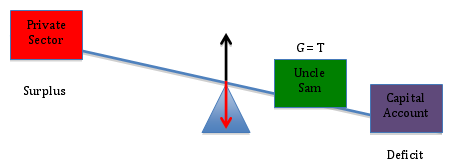

To see this in the context of the teeter-totter model, let’s initially hold the public sector’s balance constant at zero (i.e. let’s assume the government is balancing its budget so that G = T). With the government budget in balance, Uncle Sam is a “weightless” entity on the teeter-totter, so that the private sector’s financial position will simply reflect the “weight” of the capital account. Suppose, first, that the current account is in surplus (i.e. the capital account shows an equivalent deficit):

The image above depicts the benefit (to the private sector) of a current account surplus (a.k.a a capital account deficit), and it is the outcome that many of you accused me of sidestepping in my previous post. Of course, the U.S. does not have a current account surplus, so let’s address that point before moving on. (And lest anyone begin to hyperventilate, I’ll also address the fact that G ≠ T). First, the current account.

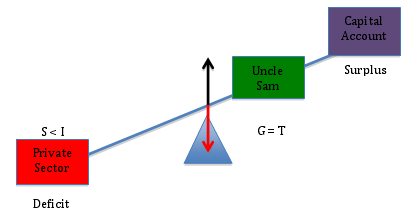

Sticking with (G = T) for the moment, we can show how a current account deficit impacts the private sector’s financial position. As the capital account moves from deficit (diagram above) into surplus (diagram below), we see that the private sector’s financial position moves from surplus into deficit.

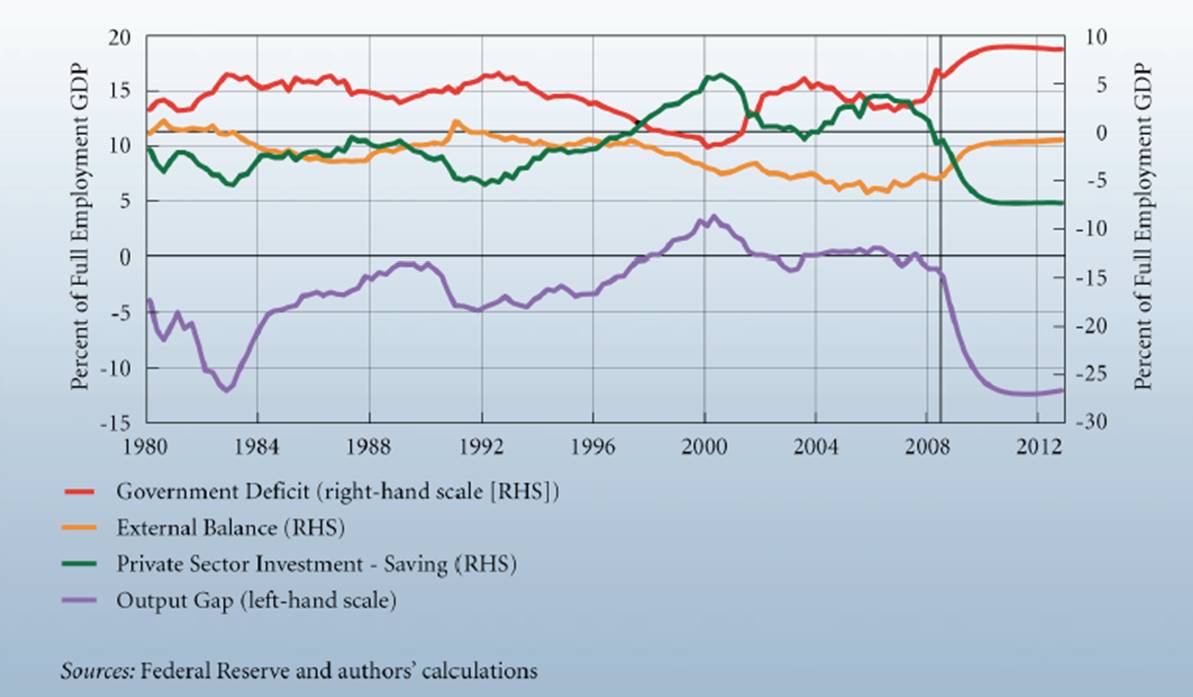

But does this all of this hold true in the real world, or is it some kind of economic chicanery? Let’s check the facts.

Equations [2] and [3] above are not based on economic theory. They are accounting identities that always “add up” in the real world. So let’s firm up the discussion about the implications of government “belt tightening” by running through some examples using the real world data found in the table below (Hat tip to Scott Fullwilir for sharing the file. All of the data comes from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) and the Flow of Funds.)

[ Click here for Sectoral Balances Data (.xlsx format) ]

Let’s begin with the data from 1998 (Q3), when the public sector deficit was just 0.01% of GDP and the current account deficit was 2.56% of GDP. Plugging these numbers into equation [2] above, the identity tells us (and the data in the table confirm) that the private sector’s balance must have been:

[2] Domestic Private Sector’s Balance = 0.01% + (-2.56% )= -2.55%

Here, we can see that the private sector’s financial position was deteriorating because it was making large (net) payments to foreigners. Because this loss of financial resources was not offset by the public sector, the private sector’s financial position deteriorated.

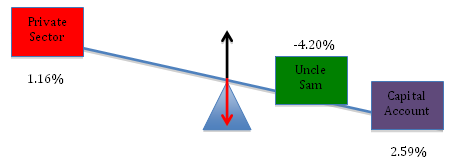

To see how a bigger government deficit would have improved the private sector’s financial position, let’s look at the data from 1988 (Q1). As a percent of GDP, the current account balance was 2.59%, nearly the same as before, while the government’s deficit came in at a much higher 4.2% of GDP. We can use Equation [2] to see effect of the larger budget deficit:

[2] Domestic Private Sector’s Balance = 4.2% + (-2.59%) = 1.61%

In this period, the private sector ends up with a surplus because the government’s deficit was large enough to more than offset the negative effect of the current account deficit.

Again, this is simply a property of the sectoral balance sheet identities. Whenever the government’s deficit is too small to offset a deficit in the current account, the private sector will experience a net loss. The result my ruffle your feathers, but it is an unimpeachable fact.

So let’s go back to President Obama’s comment and the reason I wrote this blog in the first place. The President said:

“[S]mall businesses and families are tightening their belts. Their government should, too.”

Wrong! When we tighten our belts, it means that we are trying to build up our savings. We do this by spending less. But spending drives our economy. Sales create jobs. So unless Obama has a secret plan to reverse three decades of current account deficits, the Government needs to loosen its belt when we tighten ours. If it doesn’t, then millions of us will lose our shirts.

** An aside: I am aware that I have said nothing about the usefulness of the spending projects, the waste and inefficiency that exists with many government programs, cronyism, inequality, etc., etc. These are legitimate and important questions, but they are not the focus of this analysis. I wrote this series of blogs to try to get people to understand the interplay between the private, public and foreign sectors’ balance sheets. Criticizing me for not addressing a myriad of other issues is like reading Old Yeller and complaining, “What about the cat? You’ve completely ignored the genus Felis!”

To deal with these shortfalls, states have laid off or furloughed thousands of employees, raised taxes and fees, and slashed spending on education and other social programs – some, many times over. It was supposed to balance their ’09 budgets. But it wasn’t nearly enough.

To deal with these shortfalls, states have laid off or furloughed thousands of employees, raised taxes and fees, and slashed spending on education and other social programs – some, many times over. It was supposed to balance their ’09 budgets. But it wasn’t nearly enough.