By

Robert Parenteau, CFA*

The question of fiscal sustainability looms large at the moment – not just in the peripheral nations of the eurozone, but also in the UK, the US, and Japan. More restrictive fiscal paths are being proposed in order to avoid rapidly rising government debt to GDP ratios, and the financing challenges they may entail, including the possibility of default for nations without sovereign currencies.

However, most of the analysis and negotiation regarding the appropriate fiscal trajectory from here is occurring in something of a vacuum. The financial balance approach reveals that this way of proceeding may introduce new instabilities (see

here and

here). Intended changes to the financial balance of one sector can only be accomplished if the remaining sectors also adjust. Pursuing fiscal sustainability along currently proposed lines is likely to increase the odds of destabilizing the private sectors in the eurozone and elsewhere – unless an offsetting increase in current account balances can be accomplished in tandem.

To make the interconnectedness of sector financial balances clearer, proposed fiscal trajectories need to be considered in the context of what we call the financial balances map. Only then can tradeoffs between fiscal sustainability efforts and the issue of financial stability for the economy as a whole be made visible. Absent consideration of the interrelated nature of sector financial balances, unnecessarily damaging choices may soon be made to the detriment of citizens and firms in many nations.

Navigating the Financial Balances Map

For the economy as a whole, in any accounting period, total income must equal total expenditures. There are, after all, two sides to every transaction: a spender of money and a receiver of money income. Similarly, total saving out of income flows must equal total investment in tangible capital during any accounting period.

For individual sectors of the economy, these equalities need not hold. The financial balance of any one sector can be in surplus, in balance, or in deficit. The only requirement is, regardless of how many sectors we choose to divide the whole economy into, the sum of the sectoral financial balances must equal zero.

For example, if we divide the economy into three sectors – the domestic private (households and firms), government, and foreign sectors, the following identity must hold true:

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance + Foreign Financial Balance = 0

Note that it is impossible for all three sectors to net save – that is, to run a financial surplus – at the same time. All three sectors could run a financial balance, but they cannot all accomplish a financial surplus and accumulate financial assets at the same time – some sector has to be issuing liabilities.

Since foreigners earn a surplus by selling more exports to their trading partners than they buy in imports, the last term can be replaced by the inverse of the trade or current account balance. This reveals the cunning core of the Asian neo-mercantilist strategy. If a current account surplus can be sustained, then both the private sector and the government can maintain a financial surplus as well. Domestic debt burdens, be they public or private, need not build up over time on household, business, or government balance sheets.

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance – Current Account Balance = 0

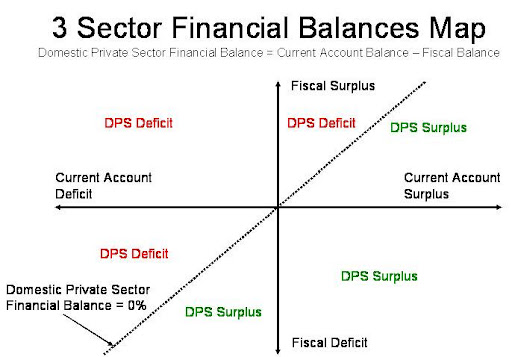

Again, keep in mind this is an accounting identity, not a theory. If it is wrong, then five centuries of double entry book keeping must also be wrong. To make these relationships between sectors even clearer, we can visually represent this accounting identity in the following financial balances map as displayed below.

On the vertical axis we track the fiscal balance, and on the horizontal axis we track the current account balance. If we rearrange the financial balance identity as follows, we can also introduce the domestic private sector financial balance to the map:

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance = Current Account Balance – Fiscal Balance

That means at every point on this map where the current account balance is equal to the fiscal balance, we know the domestic private sector financial balance must equal zero. In other words, the income of households and businesses just matches their expenditures (or alternatively, if you prefer, the saving out of income flows by the domestic private sector just matches the investment expenditures of the sector). The dotted line that passes through the origin at a 45 degree angle marks off the range of possible combinations where the domestic private sector is neither net issuing financial liabilities to other sectors, nor is it net accumulating financial assets from other sectors.

Once we mark this range of combinations where the domestic private sector is in financial balance, we also have determined two distinct zones in the financial balance map. To the left of the dotted line, the current account balance is less than the fiscal balance: the domestic private sector is deficit spending. To the right of the dotted line, the current account balance is greater than the fiscal balance, and the domestic private sector is running a financial surplus or net saving position.

This follows from the recognition that a current account surplus presents a net inflow to the domestic private sector (as export income for the domestic private sector exceeds their import spending), while a fiscal surplus presents a net outflow for the domestic private sector (as tax payments by the private sector exceed the government spending they receive).

Accordingly, the further we move up and to the left of the origin (toward the northwest corner of the map), the larger the deficit spending of households and firms as a share of GDP, and the faster the domestic private sector is either increasing its debt to income ratio, or reducing its net worth to income ratio (absent an asset bubble). Moving to the southeast corner from the origin takes us into larger domestic private surpluses.

The financial balance map forces us to recognize that changes in one sector’s financial balance cannot be viewed in isolation, as is the current fashion. If a nation wishes to run a persistent fiscal surplus and thereby pay down government debt, it needs to run an even larger trade surplus, or else the domestic private sector will be left stuck in a persistent deficit spending mode.

When sustained over time, this negative cash flow position for the domestic private sector will eventually increase the financial fragility of the economy, if not insure the proliferation of household and business bankruptcies. Mimicking the military planner logic of “we must bomb the village in order to save the village”, the blind pursuit of fiscal sustainability may simply induce more

financial instability in the private sector.

Leading the PIIGS to an (as yet) Unrecognized Slaughter

The rules of the eurozone are designed to reduce the room for policy maneuver of any one member country, and thereby force private markets to act as the primary adjustment mechanism. Each country is subject to a single monetary policy set by the European Central Bank (ECB). One policy rate must fit the needs of all the member nations in the Eurozone. Each country has relinquished its own currency in favor of the euro. One exchange rate must fit the needs of all member nations in the Eurozone. The fiscal balance of member countries is also, under the provisions of the Stability and Growth Path, supposed to be limited to a deficit of 3% of GDP. The principle here is one of stabilizing or reducing government debt to GDP ratios. Assuming economies in the Eurozone have the potential to grow at 3% of GDP in nominal terms, only fiscal deficits greater than 3% of GDP will increase the public debt ratio.

In other words, to join the European Monetary Union, nations have substantially diluted their policy autonomy. Markets mechanisms must achieve more of the necessary adjustments – policy measures are circumscribed. Policy responses are constrained by design, and experience suggests relative price adjustments in the marketplace have a difficult time at best of automatically inducing private investment levels consistent with desired private saving at a level of full employment income.

Now let’s layer on top of this structure three complicating developments of late. First, current account balances in a number of the peripheral nations have fallen, in part due to the prior strength in the euro. Second, fiscal shenanigans along with a very sharp global recession have led to very large fiscal deficits in a number of peripheral nations. Third, following the Dubai World debt restructuring, global investors have become increasingly alarmed about the sustainability of fiscal trajectories, and there is mounting pressure for governments to commit to tangible plans to reduce fiscal deficits over the next three years, with Ireland and Greece facing the first wave of demands for fiscal retrenchment.

We can apply the financial balances approach to make the current predicament plain. If, for example, Spain is expected to reduce it’s fiscal deficit from roughly 10% of GDP to 3% of GDP in three years time, then the foreign and private domestic sectors must be together willing and able to reduce their financial balances by 7% of GDP. Spain is estimated to be running a 4.5% of GDP current account deficit this year. If Spain cannot improve its current account balance (in part because it relinquished its control over its nominal exchange rate the day it joined EMU), the arithmetic of sector financial balances is clear. Spain’s households and businesses would, accordingly, need to reduce their current net saving position by 7% of GDP over the next three years. Since they are currently estimated to be net saving 5.5% of GDP, Spain’s domestic private sector would move to a 1.5% of GDP deficit, and thereby enter a path of increasing leverage.

Spain already is running one of the higher private debt to GDP ratios in the region. In addition, Spain had one of the more dramatic housing busts in the region, which Spanish banks are still trying to dig themselves out from (mostly, it is alleged, by issuing new loans to keep the prior bad loans serviced, in what appears to be a Ponzi scheme fashion). It is highly unlikely Spanish businesses and households will voluntarily raise their indebtedness in an environment of 20% plus unemployment rates, combined with the prospect of rising tax rates and reduced government expenditures as fiscal retrenchment is pursued.

Alternatively, if we assume Spain’s private sector will attempt to preserve its estimated 5.5% of GDP financial balance, or perhaps even attempt to run a larger net saving or surplus position so it can reduce its private debt faster, Spain’s trade balance will need to improve by more than 7% of GDP over the next three years. Barring a major surge in tradable goods demand in the rest of the world, or a rogue wave of rapid product innovation from Spanish entrepreneurs, there is an additional way for Spain to accomplish such a significant reversal in its current account balance.

Prices and wages in Spain’s tradable goods sector will need to fall precipitously, and labor productivity will have to surge dramatically, in order to create a large enough real depreciation for Spain that its tradable products gain market share (at, we should mention, the expense of the rest of the Eurozone members). Arguably, the slack resulting from the fiscal retrenchment is just what the doctor might order to raise the odds of accomplishing such a large wage and price deflation in Spain. But how, we must wonder, will Spain’s private debt continue to be serviced during the transition as Spanish household wages and business revenues are falling under higher taxes or lower government spending?

Part II Spain Ensnared in the EMU Trap

As evident from the financial balances map, there are a whole range of possible combinations of current account and domestic private sector financial balances which could be consistent with the 7% of GDP reduction in Spain’s fiscal deficit. But the simple yet still widely unrecognized reality is as follows: both the public sector and the domestic private sector cannot deleverage at the same time unless Spain produces a nearly unimaginable trade surplus – unimaginable especially since Spain will not be the only country in Europe trying to pull this transition off.

As an admittedly rough exercise, we can assume each of the peripheral nations will be constrained to achieving a fiscal deficit that does not exceed 3% of GDP in three years time. In addition, we will assume each nation finds some way to improve its current account imbalances by 2% of GDP over the same interval. What, then, are the upper limits implied for domestic private sector financial balances as a share of GDP for each nation?

Greece and Portugal appear most at risk of facing deeper private sector deficit spending under the above scenario, while Spain comes very close to joining them. But that obscures another point which is worth emphasizing. With the exception of Italy, this scenario implies declines in private sector balances as a share of GDP ranging from 3% in Portugal to nearly 9% in Ireland.

Private sectors agents only tend to voluntarily target lower financial balances in the midst of asset bubbles, when, for example home prices boom and gross personal saving rates fall. Alternatively, during profit booms, firms issue debt and reinvest well in excess of their retained earnings in order take advantage of an unusually large gap between the cost of capital and the expected return on capital. We have no compelling reasons to believe either of these conditions is immediately on the horizon.

The above conclusion regarding the need for a substantial trade balance swing flows in a straightforward fashion from the financial balance approach, and yet it is obviously being widely ignored, because the issue of fiscal retrenchment is being discussed as if it had no influence on the other sector financial balances. This is unmitigated nonsense. It is even more retrograde than primitive tales of “twin deficits” (fiscal deficits are nearly guaranteed to produce offsetting current account deficits) or Ricardian Equivalence stories (fiscal deficits are nearly guaranteed to produce offsetting domestic private sector surpluses) mainstream economists have been force feeing us for the past three decades. Both of these stories reveal an incomplete understanding of the financial balance framework – or at best, one requiring highly restrictive (and therefore highly unrealistic) assumptions.

The EMU Triangle

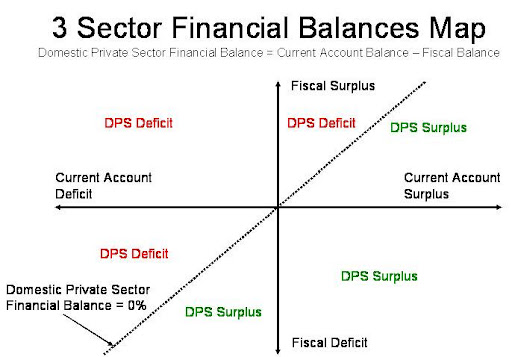

This observation is especially relevant in the Eurozone, as the combination of the policy constraints that were designed into the EMU, plus the weak trade positions many peripheral nations have managed to achieve, have literally backed these countries into a corner. To illustrate the nature of their conundrum, consider the following application of the financial balances map.

First, a constraint on fiscal deficits to 3% of GDP can be represented as a line running parallel to and below the horizontal axis. Under Stability and Growth Pact rules, we must define all combinations of sector financial balance in the region below this line as inadmissible. Second, since current account deficits as a share of GDP in the peripheral nations are running anywhere from near 2% in Ireland to over 10% in Portugal, and changes in nominal exchange rates are ruled out by virtue of the currency union, we can provisionally assume a return to current account surpluses in these nations is at best a bit of a stretch. This eliminates the financial balance combinations available in the right hand half of the map.

If peripheral European nations wish to avoid higher private sector deficit spending – and realistically, for most of the peripheral countries, the question is whether private sectors can be induced to take on more debt anytime soon, and whether banks and other creditors will be willing to lend more to the private sector following a rash of burst housing bubbles, and a severe recession that is not quite over – then there is a very small triangle that captures the range of feasible solutions for these nations on the financial balance map.

It is the height of folly to expect peripheral Eurozone nations to sail their way into the EMU triangle under even the most masterful of policy efforts or price signals. More likely, since reducing trade deficits is likely to prove very challenging (Asia is still reliant on export led growth, while US consumer spending growth is still tentative), the peripheral nations in the Eurozone will find themselves floating somewhere out to the northwest of the EMU triangle. The sharper their fiscal retrenchments, the faster their private sectors will run up their debt to income ratios.

Alternatively, if households and businesses in the peripheral nations stubbornly defend their current net saving positions, the attempt at fiscal retrenchment will be thwarted by a deflationary drop in nominal GDP. Demands to redouble the tax hikes and public expenditure cuts to achieve a 3% of GDP fiscal deficit target will then arise. Private debt distress will also escalate as tax hikes and government expenditure cuts the net flow of income to the private sector. Call it the paradox of public thrift.

As it turns out, pursuing fiscal sustainability as it is currently defined will in all likelihood just lead many nations to further private sector debt destabilization. European economic growth will prove extremely difficult to achieve if the current fiscal “sustainability” plans are carried out. Realistically, policy makers are courting a situation in the region that will beget higher private debt defaults in the quest to reduce the risk of public debt defaults through fiscal retrenchment. European banks, which remain some of the most leveraged banks, will experience higher loan losses, and rating downgrades for banks will substitute for (or more likely accompany) rating downgrades for government debt. A fairly myopic version of fiscal sustainability will be bought at the price of a larger financial instability.

Summary and Conclusions

These types of tradeoffs are opaque now because the fiscal balance is being treated in isolation. Implicit choices have to be forced out into the open and coolly considered by both investors and policy makers. It is not out of the question that fiscal rectitude at this juncture could place the private sectors of a number of nations on a debt deflation path – the very outcome policy makers were frantically attempting to prevent but a year ago.

There may be ways to thread the needle – Domingo Cavallo’s

recent proposal to pursue a “fiscal devaluation” by switching the tax burden in Greece away from labor related costs like social security taxes to a higher VAT could be one way to effectively increase competitiveness without enforcing wage deflation. Cavallo’s claims to the contrary, however, it was not the IMF that tripped him up. Fiscal cuts begat lower domestic income flows, which led to tax shortfalls, missed fiscal balance targets, and another round of fiscal retrenchment, in a vicious spiral fashion. But more innovative solutions than these, where financial stability, not just fiscal sustainability, is the primary objective, will not even be brought to light unless policy makers and investors begin to think coherently about how financial balances interact.

Or to put it more bluntly, if European countries try to return to 3% fiscal deficits by 2012, as many of them are now pledging, unless the euro devalues enough, then either a) the domestic private sector will have to adopt a deficit spending trajectory, or b) nominal private income will deflate, and Irving Fisher’s paradox will apply (as in the very attempt to pay down debt leads to more indebtedness), thwarting the ability of policy makers to achieve fiscal targets. In the case of Spain, with large private debt/income ratios, this is an especially critical issue.

The underlying principle flows from the financial balance approach: the domestic private sector and the government sector cannot both deleverage at the same time unless a trade surplus can be achieved and sustained. We remain hard pressed to identify which nations or regions of the remainder of the world are prepared to become consistently larger net importers of Europe’s tradable products, but it is also said that necessity is the mother of all invention (and desperation, its father?). Pray there is life on Mars that consumes olives, red wine, and Guinness beer.

Rob Parenteau, CFA

MacroStrategy Edge

February 22, 2010

* This article originally appeared on NakedCapitalism here and here.