By Michael Hudson

It all seems so long ago! On October 23, 2008, Alan Greenspan choked up a mea culpa for his deregulatory policy as Federal Reserve Chairman. “Those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders’ equity, myself included, are in a state of shocked disbelief,” he told the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. “The whole intellectual edifice, however, collapsed in the summer of last year.”

For a moment he seemed to be rethinking his lifelong assumption that the financial sector would seek to protect its reputation by behaving so honestly that its customers would gain from dealing with it. “I had been going for 40 years with considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well” – the idea that regulation was not needed because bankers would seek to protect their reputations and their “counter-parties” would look to their own interest.

“Were you wrong?” Congressman Henry Waxman prompted him to elaborate.

“Partially,” the Maestro replied. “I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interest of organizations, specifically banks, is such that they were best capable of protecting shareholders and equity in the firms.” The fact that they simply sought predatory gains for themselves – in the form of losses for their customers and clients (and it turns out, taxpayers”) was “a flaw in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works.”

But the past two or three years evidently have given Mr. Greenspan enough time for a re-think. In Wednesday’s Financial Times (March 30, 2011) he returns to his old job proselytizing for deregulation. His op-ed, “Dodd-Frank fails to meet test of our times,” is a mea culpa to his co-religionists for his apostate 2008 mea culpa. “The US regulatory agencies will in the coming months be bedevilled by unanticipated adverse outcomes,” he warns, “as they translate the Dodd-Frank Act’s broad set of principles into a couple of hundred detailed regulations.” The Act “may create … regulatory-induced market distortion,” because neither lawmakers nor “most regulators” understand how “complex” the financial system is.

But Mr. Greenspan refused to acknowledge the obvious: If Wall Street’s collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and other derivatives are too complex for regulators to understand, they also must be too complex for buyers and other counterparties to evaluate. This negates a key free market assumption. How can one make an informed choice without understanding the market and the consequences of one’s action? On this logic regulators would follow free market orthodoxy in rejecting derivatives and other such “complex” products.

Many critics would say that CEOs of the banks that went bust don’t understand the complexity that led to their negative equity either. Or, they know all too clearly that they can take a gamble and be bailed out by the government, simply by threatening that the alternative would be monetary anarchy that would drag down consumer banking along with casino banking. The problem is not so much complexity, but gambling – increasingly with computer models and fast mega-trading of swaps and derivatives. This is how investment bankers have made (and often lost) their money.

But they want the game to continue. That is the bottom line. On balance, even if they lose, they will be bailed out. So of course they are all for “complexity” that enables them to make gains at the economy’s expense (Mr. Greenspan’s “flaw” in the system).

But alas, he does not acknowledge the fact that Wall Street blackballs regulators who do understand how the financial system works. An ideological blind spot free-market style is a precondition for deregulators such as Mr. Greenspan. It’s as if he still doesn’t understand that this is precisely why he was hired for his job at the Fed! After rejecting Brooksley Born’s attempt to regulate credit-default swaps at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in 1998, he served his banking benefactors by passionately supporting Robert Rubin and Larry Summers in pressing the Clinton Administration to repeal Glass-Steagall, opening the door to make consumer banking dependent on wild financial gambling by the likes of Citibank and what has become Bank of America. This self-imposed blindness cost to the economy trillions of dollars and has left a dysfunctional commercial banking system. (At least former S.E.C. Chairman Arthur Levitt has apologized to Ms. Born.)

Mr. Greenspan’s euphemism for dysfunctional is “complex.” His op-ed says what priests or nuns tell parochial school pupils who ask about how God can let so many bad things happen here on earth. The answer is simply to say: “God is too complex for you to understand. Just have faith.” Nobody has sufficient skills to be “entrusted with forecasting, and presumably preventing, all undesirable repercussions that might happen to a market when its regulatory conditions are importantly altered.” Just look at how Bush Administration happy-face appointees at the FDIC and IMF expressed faith that risks were declining in 2007-08. “Regulators were caught ‘flat-footed’ by a breakdown we had erroneously thought was more than adequately reserved against.” Who could have seen that fraud was going on? Certainly nobody that was let into the Fed’s policy meetings.

Federal Reserve Board Governor Ed Gramlich’s warning about subprime mortgage fraud is ignored as an anomaly here. When Mr. Greenspan says “we” in the above quote he means the useful idiots that Wall Street insists that the government hire – true believers in the deregulatory kool-aid being doled out on behalf of their financial god too complex for mortals to know. “The problem is that regulators, and for that matter everyone else, can never get more than a glimpse at the internal workings of the simplest of modern financial systems.” But the “regulators who never got more than glimpse” were co-religionists headed by Bubblemeister Greenspan himself. He bears his failure to “more than glimpse” like a badge of honor.

It seems that only bankers really understand what they’re selling, but you must trust Wall Street to do the right thing. (If Mr. Greenspan mouthed such a claim in Wisconsin, where five school districts were suckered into borrowing $200 million in addition to their original investment in CDOs, he would meet with considerable ridicule.) If bankers do not make money for their customers, they will lose their trust. Why would bankers and financial institutions act in such a way as to profiteer at their customers’ expense (and that of the overall economy for that matter)?

The reason, of course, is that the financial sector notoriously lives in the short run. Countrywide Financial, Lehman Brothers, WaMu, Bear Stearns, A.I.G. et al. gave their managers enormous salaries and even more enormous bonuses to turn themselves into a new power elite with fortunes large and “complex” enough to endow their heirs for a century.

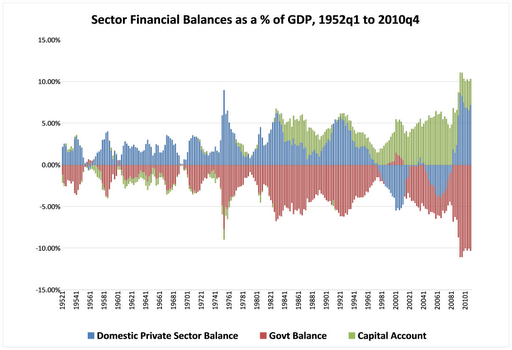

The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis has just published statistics showing that the wealthiest 1% of America’s population doubled its share of wealth over the decade ending in 2007 as the bubble reached its peak. No doubt this polarization is widening as the economy shrinks under the weight of its debt overhead. Mr. Greenspan acknowledges criticisms that Wall Street has used TARP and other bailout money simply to maintain “the outsized (to some, egregious) bankers’ pay packages.” But he points out that “small differences in the skill level of senior bankers tend to translate into large differences in the bank’s bottom line.” Skill is expensive.

What amazes me about mismanagers like Countrywide’s chairman Angelo Mozilo and his counterparts is that when the S.E.C., F.B.I. and state attorneys general open a investigation to see whether to charge them with criminal felonies, the bankers always insist that they were out of the loop, had no idea of what was going on, and are shocked, shocked, to find out that there’s gambling going on in this place.

If they are so unknowledgeable to be even more blind than the regulators and economists who warned about what was happening that has required a $13 trillion government bailout, how can they insist that they are worth whatever they can grab? For that matter, how did they manage to avoid jail terms? This is the real question that “free market” economists should be asking.

Most Wall Street firms have paid substantial settlements, and Mr. Mozilo recently paid the Securities and Exchange Commission $67.5 million to avoid going to trial for civil fraud and insider dealing. But only Martha Stewart became an insider jailbird. For Wall Street, paying a civil fine “without acknowledging wrongdoing” blocks victims from recovering civil damages in the event that they try to sue to get their money back. Evidently the Obama Administration believes that to make the banks pay would simply require yet further bailouts of “taxpayer money.” By refraining from prosecuting, Mr. Geithner at the Treasury and other regulators thus can claim to be saving taxpayers – while permitting the large banks to have grown 20 percent larger today than they were when the bailouts began, by extorting high credit card fees and penalties, and using tax breaks and almost free Fed credit such as the $600 billion QE2 to make money by fleeing the dollar to speculate in foreign currencies and make casino capitalist bets.

Mr. Greenspan insists that the economy would be even poorer under financial regulation. “One of the [Dodd-Frank] law’s provisions,” he criticizes, “made credit-rating organisations legally liable for their opinions about risks.” To avoid killing business with such regulation, “the Securities and Exchange Commission in effect suspended the need for a credit rating.” The idea was to save the ratings agencies from having to take responsibility for the tens of billions of dollars lost as a result of their pasting AAA ratings on junk mortgages.

It is as if fraud is simply part of the free market. In this respect, I find his Financial Times op-ed more damning than his evidently temporary burst of candor in his October 2008 Congressional testimony. Mr. Greenspan has rejoined his flock. And to show how thoroughly he has been cured from his temporary apostasy from free market religion, he belittles the fact that: “In December, the Federal Reserve … proposed to reduce banks’ share of debit card fees associated with retail transactions, leading many lenders to contend they would no longer be able to afford to issue debit cards.”

But can there be a better logic to promote the “public option” and have the Treasury issue credit cards as well as debt cards? The rake-off charged by banks from sellers and buyers alike (not to mention late fees that yield the card companies even more than their interest charges these days) has been a major factor eating into retail profits and personal incomes.

The banks are arguing, in effect: “If we can’t earn back enough profits to cover the losses we’ve made on our junk loans, we’ll organize our own lockout of customers – to force you to pay whatever we demand to cover our costs, pay our salaries and bonuses.” This has been their threat ever since the Lehman Brothers meltdown. They threaten to create financial anarchy if the government does not save them from loss, by shifting it onto taxpayers!

The problem is that the bankers’ solution – the inevitable result of Mr. Greenspan’s policy of shifting central planning onto Wall Street – is that it will culminate in the anarchy of debt deflation, deepening unemployment, more real estate foreclosures, and capital flight out of the dollar. So why not let the government say, “OK, we’ll provide a public-option alternative. And if this works, we’ll use it as a model for our public health insurance option. And then we will look to public banking options, and perhaps to Dennis Kucinich’s American Monetary Act to turn you commercial banks back into savings banks to stem your wild speculation at the economy’s expense.” (Just a modest proposal here for argument’s sake to quiet down the bankers’ threats.)

Mr. Greenspan argues that if banks are regulated to reduce the risk they pose to the economy, they may pack up and take their dealings to London: “concerns are growing that without immediate exemption from Dodd-Frank, a significant proportion of the foreign exchange derivatives market would leave the US.” My own response is to say fine, let them leave. Let Britain’s Serious Fraud Office and bank regulators pick up the pieces from their next opaque gamble “too complex” to understand.

Most slippery is Mr. Greenspan’s attempt to divert attention away from the instability that financial deregulation causes – the extreme and rapid polarization of wealth, the mushrooming of bad debt beyond the ability to pay, and the impoverishment of the economy as a result of its debt overhead. Don’t look there, he says; look at how “the global ‘invisible hand’ has created relatively stable exchange rates, interest rates, prices, and wage rates.” But real estate prices have not been stable – they have been inflated with debt, and then crashed the net worth of hapless borrowers. Employment is not stable, wealth distribution is not stable, nor are commodity prices, especially not the price of Mr. Greenspan’s beloved gold bullion.

Nevertheless, Mr. Greenspan concludes, there can be no such thing as a science of regulation. “Financial market behaviour is subject to so wide a variety of ‘explanations,’ especially in contrast to the physical sciences where cause and effect is much more soundly grounded.” But what sets the physical sciences apart from junk economics is the fact that it is not directly self-interested. There are no huge financial rewards for having a blind spot (except of course for scientists denying global warming or that nuclear power might be dangerous or deep-water oil drilling a risky proposition). There is method in the madness of today’s free market orthodoxy opting for GIGO (garbage in, garbage out) financial models that sing along with maestro Greenspan that Wall Street wealth will all trickle down.

“Is the answer to complex modern-day finance that we return to the simpler banking practices of a half century ago?” he asks rhetorically. By “simpler” banking practices of days of yore, he really means more honest practices, subject to knowledgeable public regulation. It was a world where banks held onto the mortgages they made rather than flipping them to third parties without any responsibility for truth in lending – or in selling, for that matter. “That may not be possible if we wish to maintain today’s levels of productivity and standards of living.” So regulation will make us poorer, not save us from financial fraud and $13 trillion bailouts.

Postulating an admittedly “as yet unproved tie between the degree of financial complexity and higher standards of living,” Mr. Greenspan suggests that wealth at the top is the price to be paid for rising living standards. But they are not rising; they are falling! have Instead of being job creators, bankers are debt creators – and debt deflation is pushing the economy into depression, raising unemployment and driving housing prices further down.

So it sounds like Mr. Greenspan today would do just what he did years ago, and reject warnings that the Fed should regulate reckless bank lending and outright fraud. His mantra is still that the invisible hand is too complex to regulate. It sounds like Willy Sutton bemoaning the fact that policemen keep interfering with his business!

For further commentary on Mr. G’s remarkable “I take it all back” op-ed, I recommend the excellent column of Yves Smith, “OMG, Greenspan Claims Financial Rent Seeking Promotes Prosperity!” Naked Capitalism, March 30, 2011. And if you still believe that Mr. Greenspan can be trusted to provide objective help to today’s financial policy makers, Google the name Brooksley Born and watch the Frontline show “The Warning.” Describing how ferociously Mr. Greenspan and his deregulatory Rubinomics colleagues fought against her attempts to provide information about derivatives so that they might be regulated (saving the U.S. government trillions of dollars), Ms. Born told her interviewer: “They were totally opposed to it. That puzzled me. What was it that was in this market that had to be hidden?”

We now know the answer. Investment bankers were making fortunes at what turned out to be public expense. And that is the real flaw in today’s financial system: most fortunes today, as in past centuries, are made by privatizing wealth from the public domain. To the grabbers, nothing must be allowed to stop that. They insist that is too complex for the regulators to cope with.