By Matthew Berg

The central insight of the sectoral balances model of the economy is that not all sectors of the economy can net-save at the same time. That means that if all those of us in the private sector in aggregate want to (on net) take in more money than we spend, then some other sector will have to spend more money than it receives. In a simple three sector version, the three sectors are the domestic private sector, the government sector, and the foreign sector.

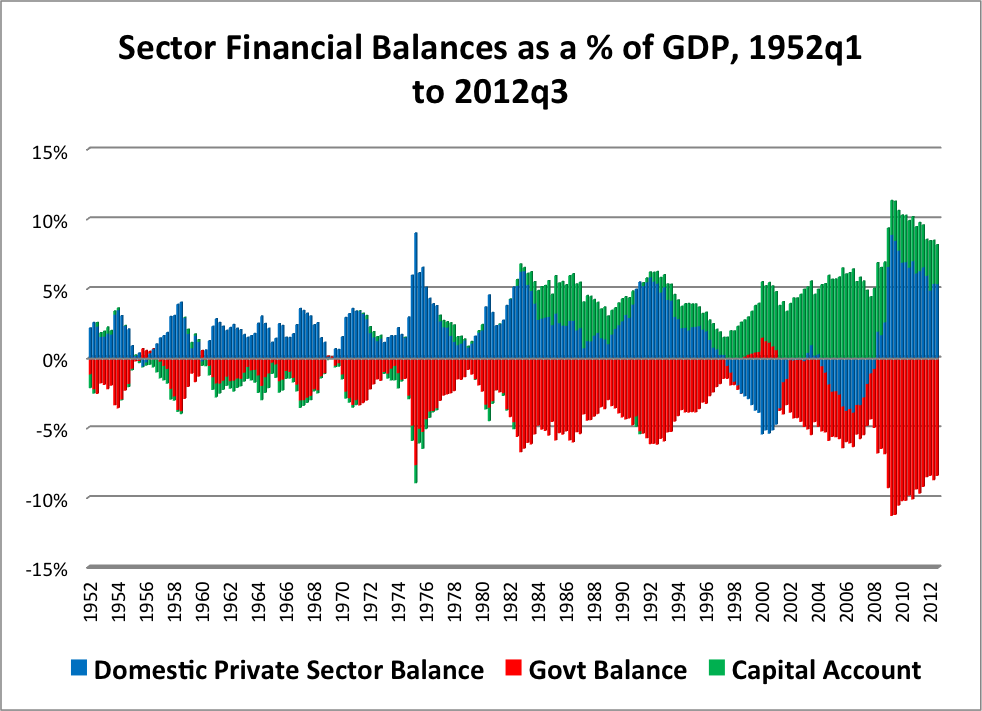

Net financial assets of all sectors in the economy necessarily add up to zero. This is clearly true – in fact, it’s an accounting identity. Interested readers can find a more thorough explanation of sectoral balances and net financial assets here, but the essential point can be seen visually in the chart below.

The bottom of the chart is the mirror image of the top of the chart:

The same thing is also true if we break down the sectors a bit further, dividing the domestic private sector into Household, Non-Financial Firms, and Financial Firms sub-sectors, and breaking down the government sector into Federal and State & Local sectors.

In fact, the same thing would be true no matter how we might choose to break down the sectors:

Sometimes, something interesting and seemingly contradictory can happen in the economy. And when it does, it has important implications for the economy’s financial stability. That interesting thing is this:

Private sector net worth can increase even if private sector net financial assets were negative, as they were from 1997 to 2008 (except for a brief period in 2003/2004).

The reason this was possible is that net worth is dependent upon valuations, whereas accounting flows are not dependent upon valuations. One important financial asset class that enters into private sector net worth calculations are stocks.

If the market price for a stock is $90 and then I buy one share of the stock from you for $100, all that changes in the transaction itself is that I have $100 less than I had previously and you have $100 more than you had previously, and I have one more share of stock and you have one less share of stock. But what also happens is that the stock’s quoted market price increases from $90 to $100.

That means that everyone else who owns a share of the same stock thinks that they are now $10 wealthier per share of stock. The same thing happens any time the stock market goes up, writ large.

And what will the stock market do? In the words of J.P. Morgan, “it will fluctuate.” We might add that the same applies to the housing market.

In fact, there is a word in common usage for what happens when private sector net financial assets go negative but net worth nonetheless simultaneously goes up. It’s called a “bubble.”

For a while, the “wealth effect” of rising stock prices may encourage people to spend more of their income or even to take on another car loan or a second mortgage. After all, if your net worth is increasing, it seems like you can afford it! And this actually does have a animating effect on the economy during the market rise – as people spend more, their spending becomes someone else’s income, which also causes government tax receipts to rise. In a bona-fide bubble such as the Dot-Com bubble or the Housing bubble, this effect is stronger still.

But as the private sector’s financial position deteriorates, enough people eventually decide that they would like to sell at the new, higher market price. And when they do, we call that a “panic” or a “financial crisis.”

It’s like a game of musical chairs. When the music stops, there are not enough chairs (net financial assets) to go around.

So while the private sector did not net save during the Dot-Com and Housing bubbles, nonetheless when people received their monthly bank statements, quarterly portfolio reports, and annual property tax assessments, they saw that the numbers were going up. Times seemed to be good.

But to those who were looking at the underlying fundamentals – private sector net financial assets – it was clear that this prosperity was built upon a house of cards. There were not enough private sector net financial assets to support the increasingly fragile financial superstructure.

Indeed, this fundamental insight harkens back to the work of Hyman Minsky, originator of the Financial Instability Hypothesis. In 1999, Randall Wray wrote a prescient policy brief entitled, “Can The Expansion Be Sustained? A Minskian View.”

After reminding us that:

“In Minsky’s view, the floor to aggregate demand provided by a deficit’s maintenance of personal income is a key stabilizing feature of the postwar big government economy we have inherited.”

And after noting that:

“if it is true that the wealth effect has been driving consumption, it is not necessary to have a crash to kill the expansion. As Godley has argued, stock market capital gains provide only a one-time boost to consumption levels; continued economic growth requires rising stock prices.”

Wray’s conclusion was emphatic:

“I know of no reputable economic theory that concludes that growing private sector deficits are any more sustainable than are growing public sector deficits, and Minsky would have concluded that rising private sector deficits are far more risky!”

Likewise, Wynne Godley outlined “Seven Unsustainable Processes” earlier in the same year, in which he warned that the “negative forces” of the government’s “restrictive fiscal stance” and of unfavorable “prospects for net export demand” “cannot forever be more than offset by increasingly extravagant private spending, creating an ever-rising excess of expenditure over income.”

Godley went on to describe, oracle-like, precisely what the private sector’s deficit meant:

“The private financial deficit measures something straightforward and unambiguous; it measures the extent to which the flow of payments into the private sector arising from the production and sale of goods and services exceeds private outlays on goods and services and taxes, which have to be made in money. While capital gains obviously influence many decisions, they do not by themselves generate the means of payment necessary for transactions to be completed; a rise in the value of a person’s house may result in more expenditure by that person, but the house itself cannot be spent. The fact that there have been capital gains can therefore be only a partial explanation of why the private sector has moved into deficit. There has to be an additional step; money balances must be run down (surely a very limited net source of funds) or there must be net realizations of financial assets by the private sector as a whole or there has to be net borrowing from the financial sector. Furthermore, a capital gain only makes a one-time addition to the stock of wealth without changing the flow of income. It can therefore, by its very nature, have only a transitory effect on expenditure. It may take years for the effect of a large rise in the stock market to burn itself out, but over a strategic time period, say 5 to 10 years, it is bound to do so.”

And in the more recent past, Rob Parenteau discerned in his 2006 public policy brief, “U.S. Household Deficit Spending” that the American economy was on a “rendezvous with reality.” What did he mean by that?:

“In other words, the U.S. household sector may be engaging in what the late economist Hyman P. Minsky would recognize as a form of Ponzi finance. Since the primary financial surplus is exhausted, and household income growth is below the average interest rate paid on household debt, household borrowing against the value of existing assets is required to sustain rampant deficit spending and to service prior debt commitments (principal and interest).Without a suitable and swift “euthanasia of the rentier,” such that interest rates fall below long-run household income growth, sustaining U.S. household deficit spending is predicated on sustaining asset bubbles.”

He also outlined three conditions that could sustain “persistently increasing private sector deficits,” recognizing that though a certain amount of private sector debt could be sustainable, too much of it would spell financial instability. These conditions were the conditions for “Hedge Finance” in Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis. Decades before Parenteau spotted the bubble economy, Minsky described three types of financing that people and firms in the private sector can adopt:

- “Hedge financing units are those which can fulfill all of their contractual payment obligations by their cash flows.”

- “Speculative finance units are units that can meet their payment commitments on ‘income account’ on their liabilities, even as they cannot repay the principle out of income cash flows.”

- “For Ponzi units, the cash flows from operations are not sufficient to fulfill either the repayment of principle or the interest due on outstanding debts by their cash flows from operations.”

The meaning of this, according to Minsky, was that:

“It can be shown that if Hedge financing dominates, then the economy may well be an equilibrium seeking and containing system. In contrast, the greater the weight of Speculative and Ponzi finance, the greater the likelihood that the economy is a deviation amplifying system.”

So, the conditions Parenteau outlined in 2006 were:

- “First, the long-run growth of private sector income must exceed the average interest rate on the debt owed by the sector. This is a necessary condition for avoiding debt trap dynamics; otherwise, interest expense commands an ever-increasing share of income.

- Second, the private sector may be deficit spending, but its primary financial balance—excluding interest expense—must be in sufficient surplus. With a primary financial surplus, income grows more than noninterest expenditures, so there is still a positive cash flow cushion before debt servicing. Less new debt must be issued to service prior liabilities.

- Third, if assets held by the private sector continue to appreciate in price at a sufficient rate, then it is possible that the growth in collateral values and capital gains will be sufficient to service existing debts and justify further lending, even to a sector that is rampantly deficit-spending.”

But after examining the data, Parenteau concluded that those conditions (again, the conditions for Minskyan “Hedge Finance”) were not met:

“On the analysis presented above, serial asset bubbles will need to be engineered in order to keep household deficit spending on a steep trajectory.”

In more general terms, we can illustrate what happens with the aid of MMT’s money pyramid.

Government IOUs (money and bonds) are on the top. Then banks and non-banks leverage their own IOUs on the government IOUs.

Now, what does it look like if we flip that pyramid upside down?

Now we have Government IOUs on the bottom, serving as the base of the economy. Bank and Non-Bank IOUs are leveraged on top of those IOUs – somewhat precariously.

In fact, you can think of the economy as a spinning top rather than a pyramid. Like a spinning top, the more top-heavy the economy becomes, the greater its tendency to instability, and the more readily it will topple over and collapse in a financial crisis.

Now, what happens if, as was the case during the dot-com bubble and the housing bubble, private sector net financial assets go negative but net worth continues to grow?

In fact, the difference between the measures of net financial assets and net worth provides us with a good rule of thumb for how to spot a bubble economy. If private sector net worth is growing at a greater rate than private sector net financial assets are growing, then that means that the economy – symbolized by our spinning top – is growing more top-heavy.

So, what happens if we make the spinning top more top-heavy? You can go ask your nearest Kindergartener – it becomes more likely to topple over.

That’s not the sort of economy we need.

What we need is not an increasingly unstable bubble economy, but rather a stable and robust economy with a solid foundation of government IOUs, to prevent it from toppling over and to fight the tendency towards financial instability.

To be clear, private sector liabilities are not always and everywhere, in any quantity whatever, disaster for the economy. As with spinning tops, so too with the economy’s asset structure – it’s all about the balance. For stable and robust growth, we need an economy with an asset structure that looks more like this, with enough government IOUs at the foundation to prevent the whole edifice from toppling over. In Minsky’s terms, we need a “Hedge” economy at most, not a “Speculative” economy and certainly not an unstable “Ponzi” bubble economy:

We must sidestep a fragile and unstable economy in which unaccountable multinational wall-street bankers arbitrarily destroy the American People’s wealth according to their own whims and caprices in unsustainable bubbles. MMT advocates a robust and stable financial system founded upon a solid structure of safe net financial assets, so that we can achieve the sort of strong and sustainable growth that the American People – and, indeed, the people of all countries – deserve. But we are being hindered from achieving that goal by man-made obstacles, which we must sweep aside in order to move forwards.

The only way to get there is by understanding how the monetary system works.

Pingback: L'analyse sectorielle permet entre autre d'évaluer la trajectoire d'une…

Pingback: The Mind Meld | The Making Sense Show

Pingback: Politically Engineered. | The Making Sense Show