By Dan Kervick

The establishment’s debt and deficit hawks have taken flight once again, this time to launch a counterassault against Paul Krugman’s sensible and increasingly successful campaign to get people to stop clutching their pearls over the federal budget situation, and to focus attention on more pressing matters of high unemployment and economic stagnation. Joe Scarborough, Ezra Klein and the Washington Post editorial board are among those springing into action on behalf of deficit worry, and against the dangerous movement of calmness and sobriety breaking out all over. One thing that becomes more apparent as this debate unfolds is that the budget warriors frequently confuse broader public policy challenges that happen to have a budgetary component with narrower problems related to size of the budget deficit itself. A recent Atlantic piece by Alan Blinder unfortunately contributes to that confusion.

There is no secret about the fact that there are a lot of people who wish to shift many of the responsibilities that are currently borne by the federal government to the private sector. Others wish either to maintain the federal government’s responsibilities as they are, or else increase the government’s responsibilities. These are important debates. What they hang on are questions about whether the private sector or the public sector is more effective in delivering certain kinds of goods and services.

What these debates don’t hang on, or shouldn’t hang on, is the current size of the federal deficit or debt. How we manage the financing of our federal government’s spending commitments, given the choices we have made about what those commitments ought to be, is separate from questions about whether the government should or should not be taking on those commitments in the first place. It is true that there might be certain goals that we would like to achieve but that our society just can’t afford to pursue because of limits on our real resources. But the government is an agent of the society as a whole, so there is no meaningful sense in which the government can’t afford to do something that the society can afford to do. If there is something that we can achieve as a society and that we have decided is the proper job of government, then we can always financially empower the government to carry out our wishes.

Consider the case of health care. Many people claim that we are facing a social crisis over the long-term path of our health care expenditures. But if there is indeed a crisis over our society’s total projected long-run health care obligations, then we need to label it as such. It’s not a deficit problem, or a public debt problem, and pretending it can be addressed by “fixing the debt” or reducing the government’s deficit is, at best, simply an irresponsible punt. At worst, it is a dishonest attempt to exploit public fear and confusion over budgetary matters in order to push Americans into accepting a less prosperous and more unequal society in which the wealthy continue to detach themselves from the rest of the country and its shared commitments, and force the less affluent to accept a lower overall level and quality of health care.

Consider this analogy: Suppose there is a dam outside your city that is owned and operated by that city and its government. The dam is essential for flood prevention, electricity generation and providing the city with its water supply. But it is in bad repair and crumbling, and every year the city’s emergency dam maintenance expenditures have been going up. Ultimately, the city will either have to spend a lot of money in a short period of time to repair the dam for good, or else accept mounting annual maintenance costs that over the long run will cost much more than the one-time repair. Now suppose a city councilman rises to speak, “We have to do something about this dam problem! We must reduce our long-term dam maintenance budget!” I think it would be obvious to people that reducing the maintenance budget alone has nothing to do with addressing the problem. Deciding not to spend money to address a growing problem is not the same thing as fixing that problem.

It is possible that our pseudo-responsible councilman might also recommend selling the dam to a private sector firm, letting that firm provide the city with its electricity, water and flood prevention services, while also carrying out any needed maintenance. But here again we should note that you also don’t fix the crumbling dam problem simply by selling the dam to a private utility company which will then take on responsibility for those burdens, and tack the dam maintenance costs onto everybody’s water and electricity bill. The people of the city will pay either way. Maybe it makes sense to sell the dam; maybe it doesn’t. But there is no argument to be made for privatizing the dam based just on pointing out that the cost of maintaining the dam will shift from the public’s tax bills, payable to the city, to their water bills payable to a private company.

So it’s just totally dishonest to say about any problem, “We have to reduce the public commitment, because the government will never be able to afford this”, while saying with the same breath that the whole society will be able to afford it. If the society can afford it, then obviously the government can afford it since the government is just an agent of the society. The separate debate about public provision vs. private provision is a debate about delivery mechanisms, not about budgets and affordability.

The same moral should be drawn when we shift the discussion from dams to health care. Suppose under current projections our society will spend $X on health care in 2025, of which $Y is projected to be spent by the federal government, and $(X-Y) by private sector accounts. Suppose we then reduce our long-term deficit by reducing the 2025 public health care commitment to $Z, where Z is some amount that is less than Y. So far that that means only that the expected private commitment goes up to $(X-Z), and the private sector is now on the hook for the difference between $Y and $Z. Either way the society’s total commitment remains $X.

If there is indeed a long run health care spending crisis for our society, there are only two ways of addressing the crisis, and they both require policies that address our society’s total health care expenditures, public and private combined:

a. Reduce the cost of health care delivery over time via efficiencies and productivity increases, so we get the same health care bang for the same amount of real expenditure.

b. Reduce the overall amount of health care that is delivered over time per capita, so that the amount actually delivered in 2025 is less than what is currently projected.

Of course, we will probably employ a combination of both strategies. But whatever we do, we can see that the name of the game is to address the total social cost of health care. The question of what roles should be played by the public sector and private sector respectively, and what happens to public and private health care budgets as a result, is a separate further question.

The approach I favor, and that has long been favored by many other progressives, is to rely more on the public sector as a purchaser of health care, to leverage the public’s purchasing power in an organized way power to drive down waste and demand efficiency in the health care sector, and thereby reduce the amount of the total expenditure drained off of by extravagant and unnecessary profit-taking and rent-seeking. We can have more efficient, better quality and more equally distributed health care at a lower overall social cost if we get serious about using the latent monopsony power of the American people as a unified bloc of consumers of health care.

Alan Blinder recently addressed the issue of long term health care spending in a piece in the Atlantic. But he does so obliquely, and unfortunately his deficit-focused discussion seems to be a classic case of the “councilman’s punt” that I discussed earlier. Blinder tries to address the issue of the role of health care spending on the federal budget in isolation from the larger question of the total social cost of health care and the best means of providing that health care. And he bases his case for reduced federal commitment on arbitrary numbers and budget targets with no discernable independent public policy motivation. The result is a very unconvincing case.

Blinder begins by saying that we have a “truly horrendous” long-term budget problem attributable to health care:

The truly horrendous budget problems come in the 2020s, 2030s, and beyond. But while the long-run budget problem is vastly larger, it is also far simpler, for two reasons. The first is that the projected deficits are so huge that filling most of the hole with higher revenue is simply out of the question. Spending cuts must bear most of the burden. The second is that there is only one overwhelmingly important factor pushing federal spending up and up and up: rising health care costs.

He then adds:

Any serious long-run deficit-reduction plan must concentrate on health care cost containment. Simpson and Bowles knew this, of course. But they didn’t know how to “bend the cost curve” sufficiently. Neither does anyone else. So they just recommended a target–holding the growth rate of health care spending to GDP growth plus 1 percent. In short, Simpson and Bowles, brave as they were, punted on the most critical issue.

But as we have seen, this is a blinkered approach to the health care problem. If public expenditures are projected to grow as a result of increasing social health care costs, it makes no sense to address this problem simply by reducing the planned public side of the expenditures – as though the government’s obligations stop at the border drawn by its current budget, and as though health care spending outside the federal budget is someone else’s problem. The government is not just some kind of big human resources department that might decide, due to anticipated revenue decreases, to cut back on the dental benefits it provides its employees, and let the employees pick up the cost of cleanings and fillings themselves. The government’s role is to consider the public good in a holistic fashion, and decide on the best mechanisms for pursuing that good. And a national government’s options for commanding and organizing the resources the country has available to meet its social challenges are much less limited than the private company’s options. The company can’t just decide to lay control to a larger portion of society’s resources, without increasing its sales, in order to provide its employees with expanded dental coverage. A government has no such sales constraint on its revenues, and its power to claim resources and organize their use for public purpose is far broader. So the only question then is whether it makes more sense for the public sector or private sector to carry out the kinds of health care expenditures in question.

An obvious response to Blinder here is to say that if the volume of health care expenditures is projected to increase, and it makes sense for the public to carry out those expenditures through such programs as Medicare, or an expanded and progressive single payer system, then the government will simply have to increase its tax revenues. If the public wants to spend a certain amount on health care, and they want the government to organize the disbursements, then they need to turn over some appropriate amount of revenue to the government. But Blinder says that addressing the public health care commitment problem can’t come simply from more taxes, or even equal amounts of tax increases and federal budget cuts, but must come from “mostly cuts.” This position is illogical. If the private sector can cough up some quantity $X in additional spending to pick up the health care spending slack caused by reduced government commitment to health care, then it can surely come up with $X in additional tax payments to fund an the same amount of spending through the public treasury. Cutting the federal health care budget is not the same things as cutting the amount our society spends on health care.

So why does Blinder think the only solution is cuts? He puts forward an arbitrary criterion for thinking about public policy decisions and revenues – an 18.5”% rule. After considering the possibility that US government revenues might rise to a larger share of GDP, Blinder says this:

There are four takeaways. One: The interest bill–which is the vertical gap between primary spending and total spending–eventually comes to dominate the budget. Two: Historically normal levels of taxation (the bottom line) do not come close to covering even primary spending (the middle line), not to mention interest payments. Three: Primary spending as a share of GDP rises steadily, from 22 percent of GDP now to over 32 percent by the 2080s. Four: The government can cover no more than a small fraction of the projected deficits by raising taxes. Sorry, Democrats, but the Republicans are right on this one. Americans are used to federal taxes running about 18.5 percent of GDP; they will not allow them to rise to 32 percent of GDP. Never mind that a number of European countries do so; we won’t.

This is a rather imperious and groundless statement, issued on behalf of all Americans, about what they will and won’t allow, and might or might not choose to do in the future. Whether Americans are willing to pay more for a given government service surely depends on what they conclude about the quality of that service, and about whether entrusting it to government saves money for them elsewhere. I wonder what Americans would think if they were told their tax bill was going up, but all of their out of pocket health and dental care expenses were going to disappear.

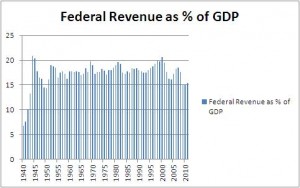

Blinder bases his case for the 18.5% rule on the historical record of federal tax revenues as a percentage of GDP:

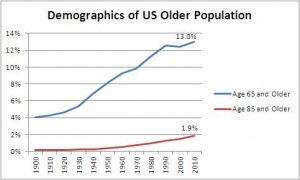

In fact, federal revenues have exceeded 18.5% a few times. But that’s not what is really important here. Here is another historical record, the percentages of the population over the ages of 65 and 85 respectively:

Should we say that since the over-65 population of the US has never been greater than 13%, then Americans “will not allow” that percentage to ever grow higher? Of course not. One can’t simply look at a path of percentages over time and declare that the maximum previous numbers are the cap beyond which the public will never permit a large number. That’s not scientific public policy thinking. It’s numerology.

There are also some options for public financing of health care that Blinder doesn’t consider. If revenues as a share of GDP don’t increase, but government spending as a share of GDP – driven by health care – does increase, then on the mainstream picture the difference will have to come from public borrowing, and as a result the interest payments on the public debt will grow. Depending on the volume of the growth, that might create a long-run sustainability problem, as Blinder notes. But for monetarily sovereign governments like the United States, the option always exists of spending in excess of the total amount borrowed or collected in taxes. In other words, the government can engage in functional finance. While MMTers have long endorsed functional finance and have studied its ramifications, an increasing number of mainstream figures are beginning to engage with the functional finance option, including Adair Turner and Martin Wolf.

But both mainstreamers and MMTers recognize that if there are substantial increases in the size of the federal budget as a share of GDP over time, then taxes will likely have to go up to cover at least part of that increase. Taxes are a tool for shifting resources from private control to public control. The conventional picture is that the money that is taxed comes from some mysterious private sector source, and must first be captured from the private sector by the government so that it can then used to purchase goods and services. The MMT view is that the government provides the money to the private sector in the first instance and then taxes it back to give the currency value and sustain the demand for the currency. At full economic capacity, the government also increases taxes so that it can increase its own contribution to the aggregate demand for goods and services without enabling dangerously inflationary private sector competition for those goods and services beyond what the society is capable of producing. Either way, taxes are part of the process by which the government provisions itself with resources and procures services from the private sector. So if there is an increased public responsibility for the provision of some kind of good, there will generally be at least somewhat more taxation.

Where Blinder goes wrong is in declaring an arbitrary cap of federal revenues as a share of GDP somewhere in the vicinity of 18.5%. This idea that there is a permanent limit on the size of government baked into the budgetary DNA of the American republic is without warrant. Progressives should continue to press forward aggressively with calls to boost the public responsibility for health care without worrying that they will exceed Alan Blinder’s budgetary speed limit.

Pingback: Austerity, MBTA, Blinder | Dollars & Sense Blog

Pingback: Blinder Leading the Blind | Fifth Estate

Pingback: Budget Wars Roundup « Multiplier Effect