Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

Monthly Archives: October 2011

Corruption and Crony Capitalism Kill

The recent Turkish earthquake, as with its modern predecessors, has shown that the witches’ brew that crony capitalism produces is a leading cause of death and severe injury. Control fraud, the use of a seemingly legitimate entity by those that control it to defraud, exists in all three major sectors – private, public, and non-profit. Crony capitalism typically involves the interaction of public and private sector control fraud. I have written primarily about accounting control frauds, which are property crimes of mass destruction. Anti-customer, anti-public, and anti-employee control frauds can all cause mass casualties. Earthquakes and the tsunamis they produce can kill hundreds of thousands of people. Government programs have been exceptionally successful in reducing the loss of life from natural disasters. Early warnings, evacuation routes, barriers, and training can greatly reduce the losses caused by tsunamis. Seismic building codes, if properly enforced, can reduce direct deaths from earthquakes to exceptionally low levels even in severe seismic events. The saying is: earthquakes don’t kill people; collapsing structures do.

Comments Off on Corruption and Crony Capitalism Kill

Posted in William K. Black

MMP Blog #22: Reserves, Governement Bond Sales, and Savings

Last week, we showed that government deficits lead to an equivalent amount of nongovernment savings. The nongovernment savings created will be held in claims on government. Normally, the nongovernment sector prefers to hold that much of that savings in government IOUs that promise interest, rather than in nonearning IOUs like cash. This week, we will look at this in more detail.

Bond sales provide an interest-earning alternative to reserves. We can say that short term treasury bonds are an interest earning alternative to bank reserves (as discussed earlier reserves at the central bank often do not pay any interest; if they do pay interest, then government bonds are a higher-earning substitute). When they are sold either by the central bank (open market operations) or by the treasury (new issues market), the effect is the same: reserves are exchanged for treasuries. This is to allow the central bank to hit its overnight interest rate target, thus, whether the bond sales are by the central bank or the treasury this should be thought of as a monetary policy operation.

Reserves are nondiscretionary from the point of view of the government. (In the literature, this is called the “accommodationist” or “horizontalist” position.) If the banking system has excess reserves, the overnight interbank lending rate falls below the target (so long as that is above any support rate paid on reserves), triggering bond sales; if the banking system is short, the market rate rises above target, triggering bond purchases. The only thing that is added here is the recognition that no distinction should be made between the central bank and the treasury on this score: the effect of bond sales/purchases is the same.

There is a surprising result, however. Since a government budget deficit leads to net credits to bank deposits and to bank reserves, it will likely generate an excess reserve position for banks. If nothing is done, banks will bid down the overnight rate. In other words, the initial impact of a budget deficit is to lower (not raise) interest rates. Bonds are then sold by the central bank and the treasury to offer an interest-earning alternative to excess reserves. This is to prevent the interest rate from falling below target. If the central bank pays a support rate on reserves (pays interest on reserve deposits held by banks), then budget deficits tend to lead banks gaining reserves to bid up prices on treasuries (as they try to substitute into higher interest bonds instead of reserves)—lowering their interest rates. This is precisely the opposite of what many believe: budget deficits push interest rates down (not up), all else equal.

Central bank accommodates demand for reserves. Also following from this perspective is the recognition that the central bank cannot “pump liquidity” into the system if that is defined as providing reserves in excess of banking system desires. The central bank cannot encourage/discourage bank lending by providing/denying reserves. Rather, it accommodates the banking system,providing the amount of reserves desired. Only the interest rate target is discretionary, not the quantity of reserves.

If the central bank “pumps” excess reserves into the banking system and leaves them there, the overnight interest rate will fall toward zero (or toward the central bank’s support rate if it pays interest on reserves). This is what happened in Japan for more than a decade after its financial crisis; and what happened in the US when the Fed adopted “quantitative easing” in the aftermath of the financial crisis that began in 2007. In the US, so long as the Fed pays a small positive interest rate on reserves (for example, 25 basis points), then the “market” (fed funds rate) will remain close to that rate if there are excess reserves.

Central banks now operate with an explicit interest rate target, although many of them allow the overnight rate to deviate within a band—and intervene when the market rate deviates from the target by more than the central bank is willing to tolerate. In other words, modern central banks operate with a price rule(target interest rate), not a quantity rule (reserves or monetary aggregates).

In the financial crisis, bank demand for excess reserves grew considerably, and the US Fed learned to accommodate that demand. While some commentators were perplexed that Fed “pumping” of “liquidity” (the creation of massive excess reserves through quantitative easing) has not encouraged bank lending, it has always been true that bank lending decisions are not restrained by (or even linked to) the quantity of reserves held.

Banks lend to credit-worthy borrowers, creating deposits and holding the IOUs of the borrowers. If banks then need (or want) reserves, they go to the overnight interbank market or the central bank’s discount window to obtain them. If the system as a whole is short, upward pressure on the overnight rate signals to the central bank that it needs to supply reserves.

Government deficits and global savings. Many analysts worry that financing of national government deficits requires a continual flow of global savings (in the case of the US, especially Chinese savings to finance the persistent US government deficit); presumably, if these prove insufficient, it is believed,government would have to “print money” to finance its deficits—which is supposed to cause inflation. Worse, at some point in the future, government will find that it cannot service all the debt it has issued so that it will be forced to default.

For the moment, let us separate the issue of foreign savings from domestic savings. The question is whether national government deficits can exceed nongovernment savings in the domestic currency (domestic plus rest of world savings). From our analysis above, we see that this is not possible. First, a government deficit by accounting identity equals the nongovernment’s surplus (or savings). Second, government spending in the domestic currency results in an equal credit to a bank account. Taxes then lead to bank account debits, so that the government deficit exactly equals net credits to bank accounts. As discussed,portfolio balance preferences then determine whether the government (central bank or treasury) will sell bonds to drain reserves. These net credits (equal to the increase of cash, reserves, and bonds) are identically equal to net accumulation of financial assets denominated in the domestic currency and held in the nongovernment sector.

We conclude: since government deficits create an equivalent amount of nongovernment savings it is impossible for the government to face an insufficient supply of savings.

RIP Shareholder Value Meme: Make Way for A New World

By Rob Parenteau and Marshall Auerback

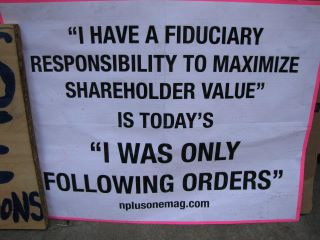

We have never quite been able to pin down why “maximize shareholder value,” the mantra of the world in which we have both worked for the past three decades, always left us with a bad feeling. But considering the actions of the markets over the past few days, particularly the perverse response to the consolidation of the rentier class’s power grab in Europe (which will consign millions of people to years of poverty and indentured servitude), it is easier to understand a little better why.

There is perverse logic at work here. You’re a fund manager who, at the start of the fourth quarter, was down 25%. Neither hard to do nor a particular sign of incompetence, given the uncharacteristically huge volatility, the hidden role of derivatives, the highly “politicized” nature of the markets themselves, etc. A market that rises 4% in Q4 doesn’t really help you. But if you’re up 15% in Q4 and therefore “only” down 10% for the year or, even better, UP for the year, then you might be able to stay in the game a bit longer. So you have a massive incentive to play in the casino, under the guise of “maximizing shareholder value.”

It’s sort of like managing one of the so-called Too Big To Fail (TBTF) banks now. You know you’re basically insolvent. You know the game is going to end at some point and, if and when rationality returns, your bank will be restructured (maybe via an FDIC forced takeover a la WaMu) and you’ll be out of a job. So you get even more reckless in the meantime, inflating the numbers as much as possible via accounting tricks and taking the huge “performance” bonuses which accrue to you. It is the fund management equivalent of Bill Black’s control fraud writ large.

Of course, as Bill always points out, the “F” word (fraud) is never taken seriously in the economics profession. In fund management, there’s another “F” word which is now pervasively ignored – “Fiduciary” as in “fiduciary responsibility.” The same control fraud dynamics at work in both areas. “Cash is trash,” as the system is set up to force the fund manager to play.

The funny thing is, the looters inside the banks used the phrase “shareholder maximization” to con the shareholders into believing they too would be taken along for the ride to mega riches. In the case of Lehman, AIG, etc. the true nature of the con was revealed. The insider managers operating both simple and elaborate control fraud schemes often walked away quite wealthy, the shareholders got little more than an invitation to the back row of the bankruptcy court.

What is truly amazing is that shareholders, fund managers, retail investors, etc. fell for this over and over and over again, perhaps because the Grifters and psychopaths in the corner office were just that good, or perhaps because they wanted to believe and so suspended disbelief, or perhaps because it was the only game left in town and they did see some shareholders get very wealthy by financing what we will one day soon understand were the storm trooper MBAs working their best reptilian angles to plunder and pillage the last spoils of the empire of global, fully deregulated, cowboy/casino capitalism. We speak as market practitioners, who are keen to see capital markets work the way they are supposed to: finance as the handmaiden to industry, and not the other way around. Gresham’s Law is operative here as well: bad money is driving out good. It needn’t be this way.

RIP, shareholder value meme. You were a pretty damn powerful one, almost as powerful as TINA. Arise AWIP (“another world is possible”), new true stakeholder economy, which can trump TINA. Because the old structures are corrupt to the core. And at some level we all have known it, but we haven’t known how we could effectively contest it and change it. Perhaps the Occupy Wall Street protests growing around the world is finally showing us another way.

* TINA = There Is No Alternative (Myth killed here)

Comments Off on RIP Shareholder Value Meme: Make Way for A New World

Posted in Marshall Auerback, rob parenteau, Uncategorized

Tagged curse of tina, Marshall Auerback, rob parenteau, shareholder value

Bank of America’s Death Rattle

Comments Off on Bank of America’s Death Rattle

Posted in William K. Black

Tagged #econ4the99, bank of america, fdic, Federal Reserve, merril lynch, paul jay, the real news

Marshall Auerback on CBC’s Lang and O’Leary Exchange

“The ECB is the only entity that can create literally trillions of euros till the cows come home..that’s not really issue, the fundamental problem is that you have a currency union without a fiscal structure…”

Watch here (Marshall comes in at about 16:00)

Comments Off on Marshall Auerback on CBC’s Lang and O’Leary Exchange

Posted in Marshall Auerback, Uncategorized

Tagged ECB, Fiscal Policy, Marshall Auerback

Pavlina Tcherneva on at Issue with Ben Merens

Comments Off on Pavlina Tcherneva on at Issue with Ben Merens

Posted in Pavlina R. Tcherneva

Boots on the Ground

Comments Off on Boots on the Ground

Posted in Uncategorized, William K. Black

Tagged #econ4the99, #occupywallstreet, #ows, William K. Black

Budget Deficits and Saving: Responses to Comments on Blog 21

Sorry this is late—there were a lot of comments and I amtraveling. Before we begin, a note and plea: we are getting an increasingnumber of emails with comments and questions (sent to NEP email and to mine).Please understand I cannot respond to those—I get hundreds of emails a day andit would consume all of my time to respond individually. That is why I amcollecting comments on the Primer page and responding to all at once. I knowsome people are having trouble posting comments (I do too!) but what I’ve foundis that “three’s a charm”: if you hit “post” three times it inevitably works.Sorry about that.

Some of the comments were quite long and dealt with severalissues. So this week I am posting most of the text, followed by my response.

Iris: So from my point of view, what you obviously neglectis to insert all the additional references to presupposed material, which us,especially with less “previous knowledge of MMT” could help to betterunderstand the matter you’re dealing with. My impression is for example, thatnot only general accounting basics are necessary but also knowledge about thestructural system of inter-firm-, inter-bank- and governmentbanking-institutions’ accounting to private sector. Would it be asked

to much of a favor for you to perhaps offer, at least via footnotes, thesehints too?

to much of a favor for you to perhaps offer, at least via footnotes, thesehints too?

A: Well there is always a trade-off. We don’t want to getinto defining the meaning of “the” (as a former President tried to do). I dopresume some knowledge and it is tricky just how much should be assumed and howmuch explained in detail. Sometimes the reader with less background is probablygoing to have to accept some statements without fully understanding all thedetails behind them. I have been leaving out detailed accounting for tworeasons: it is more detail than most will want, and it is hard to produce thesein Word (and I have no idea how hard it is for our techie to post them to theblog). However, since there have been a number of requests, I will devote ablog to “T Accounts”.

Hugo: Ok, “excess deposits” results in increased”demand for profitable savings vehicles”. And if demand for savingsvehicles exceeds supply, the market will adjust. Savers will have to acceptlower yields on their savings. Firms would find it more easy to borrow money.Interest rates for corporate bonds would likely decrease (in thefinancial markets?). But I feel the transmission to an increase in governmentbonds is somewhat weak here? What you are suggesting seems to be: “Excessdeposits seeking profitable savings vehicles” -> “excessreserves in the interbank lending system” -> “overnight ratemaintenance” -> “bond sales” -> “equilibrium”..?But how does “excess deposits” necessarily lead to “excessreserves” here?

A: Before I get into a response, Guest responded to Hugo,trying to straighten this out:

-Guest:It is a result of double-entry book keeping. Whenever government creditsdeposits of someone in the banking system, it alse credits banks reserves tocreate asset that offsets banks deposit liability.

A: OkI am not sure what an excess deposit would be. When I get my paycheck mydeposit goes up and surely I do not think it is excessive. I then buyconsumption goods and services. I might also make some portfolio decision overwhat is left, allocating some of my accumulated savings to higher earningfinancial assets. Hugo says I might bid up bond prices, on both private andgovernment debt, lowering interest rates on the outstanding stock. Right. He isnot convinced that a government deficit will put downward pressure ongovernment bonds, however, because he does not see how my “excess deposits”creates “excess reserves”. Remember that reserves are on the asset side of thebank’s balance sheet while deposits are on the liability side. When governmentmakes a payment, both sides go up—the bank’s reserves at the Fed are credited,and my demand deposit is credited. Most of those additional reserves will beexcess reserves (details on this are complicated as reserve requirements arecalculated after a lag—let us ignore those details for now). Banks make aportfolio decision: buy something that earns higher interest rate. First theycan lend in the overnight, fed funds, market, pushing that rate down. Next theycan buy a close substitute, treasuries (government bonds), and then diversifyinto other assets. (Note: unless they buy treasuries from the central bank,this shifts reserves about but does not reduce aggregate reserves.) Sincecentral banks target an interest rate (ie: the fed funds rate in the US) theywill react once the interest rate falls below the target. They will begin tobuy treasuries. That eliminates the excess reserves and the downward pressureon interest rates.

-Luigi: “The impact of the deficiton bank reserves has been emphasized by the neo-chartalist school (Bell2001; Wray 1998), but neochartalist writers do not explicitly draw on theconclusion that it supports the complete exogeneity of the long-term rateof interest”. Parguez writes this in 2004, it’s right? How MMT considerlong-term rates of interest?

A: Sounds OK to me. A central bank CAN target a long termrate (ie 30 year treasury bond) and hit it if it wants, but central banksnormally do not. Instead, they target the short end and when they want thelonger term rates to fall, they make statements like “we expect to hold theovernight rate at a low level for the foreseeable future”. That makes holdersof longer maturity bonds more confident that the short term rate will not risesoon—which would cause capital losses. There are a number of approaches to thedetermination of longer term interest rates: expectations theory, habitattheory, and interest rate parity. As a great philosopher once said “you canlook it up”. But in conclusion, yes, MMT agrees that longer rates are complexlydetermined and are not normally exogenously controlled by central banks.

WH10: “Finally, the fear that government might “printmoney” if the supply of finance proves insufficient is exposed as unwarranted.All government spending generates credits to private bank accounts—which couldbe counted as an increase of the money supply (initially, deposits and reservesgo up by an amount equal to the government’s spending).”That’s only halfthe picture for those concerned. Peopleperceive govt spending as being counteracted by bond sales, so the money supplyseemingly does not go up. HOWEVER, is itnot the reality that a significant proportion of bond sales come from bankPrimary Dealers, which ‘spend’ from their reserve accounts, such thateffectively there is a net credit to deposit accounts (as opposed to them beingoffset by purchases of bonds out of deposit accounts)? In other words, it seems we’re almost always’printing money,’ if this is the case.

A: Minsky said: “anyone can create money (things), theproblem lies in getting it accepted”. Yes, we are almost always “printingmoney” in the sense of issuing IOUs denominated in the state money of account.Get over it. On some conditions, that can cause prices of output or offinancial assets to rise. It all depends. There is no automatic channel thatcauses an increase of “money supply” however defined to lead to “inflation”,however defined. And there is nothing that magical with respect to inflationeffects of government spending as opposed to private spending. If I get an autoloan to buy a car, on some conditions that could push up car prices and hencethe CPI. And we could find that some measure of the money supply also hadincreased. If government strokes some keys to add a vehicle to its fleet ofcars, on some conditions that could push up car prices, the CPI, and somemeasure of the money supply. Yes, it is a possible outcome and if you reallywant to point your finger at the increase of the money supply, I guess you can.I would say that it was the increased purchase of autos that in tight markets(full employment, full capacity utilization) would induce manufacturers toincrease prices. Note that could also happen without any additional loans or“printing money”.

WH10: Was there a time when did the U.S. Govt could spendbefore requiring the Treasury’s account to be marked up? If we imagine afiat currency starting out, but Fed overdrafts are not allowed and the sameinstitutional restrictions that we have today are in place, then what are theaccounting statements which allow the government to spend without a positiveaccount? Does this necessitate the existence and willingness of primarydealers that to have their reserve accounts go negative to facilitategovernment spending? Why are they willing to do this?

A: Not exactly sure when the US government decided to tieits shoes together by requiring Treasury to have a credit to its account at theFed before making a payment, but it could date to creation of the Fed in 1913. Whatif there were no Fed? Bank clearing could take place on the books of theTreasury, and the Treasury could simply credit them with reserves whenever itmakes a payment. Even simpler, it could just pay with paper notes or coins. Or,in the old days, with tally sticks. These would be the debt of the governmentand the financial assets of the nongovernment, accepted in tax payment.

Dave: I guess I’ve missed something (though I’ve reviewedthe two previous posts): Given that reserve requirements are defined by the Fed(http://www.federalreserve.gov/…how does the non-governmental sector as a whole acquire “excessreserves” i.e. don’t reserves only grow as much as (in proportion to) thesurplus the non-governmental sector accumulates from deficit spending? Or doyou only mean that SOME agents/banks/actors of the non-governmental sectoraccumulate “excess reserves”? Or….?

A: Banks can get reserves from either the central bank orthe treasury. When treasury buys goods and services, bank reserves arecredited. We normally call that government spending. When the central bank buysfinancial assets from banks (ie: buys government bonds, or private debt, or theIOUs of a “borrowing” bank) that also increases bank reserves. But we do notnormally call that “government spending”. Really it is, but it is spending onassets not on goods and services (so does not show up in GDP).

Joe: OK, so we’re starting to get to the answer of”What if people don’t want to buy the bonds?” Perhaps some examplenumbers, accounts etc. would make thing a bit more concrete as ‘portfoliopreference’ is rather vague. Also, the idea the deficit spending comes first,to provide the reserves to purchase the bonds, seems logical(money must existbefore you can buy bonds), but doesn’t the treasury need a positive balance inorder to spend? Bond sales increase the balance, so there’s a very strongillusion that the proceeds from bond sales are recycled into the treasury’saccount (which I believe is the traditional, pre-1971 view). Did theinterpretation just change in 1971; pre-1971 money from bond sales went intotsy account, post-1971 cash assets are converted to bond assets while new moneyis put into tsy accout? And how can the deficit be mandated to be covered bybonds, if you have to wait for preferences to adjust, there must be some timelag between spending and bond ales? (sorry, lots of questions, I’mpatient, hopefully it’ll all clear up in the coming weeks)

A: Not sure how numbers would help. In the US, where we tiedthe government’s shoes together, the Treasury first sells bonds to specialbanks that buy them by crediting the Treasury’s deposit account. Treasury movesthe account to the Fed before spending. These bonds will be bought by thespecial banks, so at this point the portfolio preferences of the nongovernmentsector do not matter. Deficit spending will increase bank reservesdollar-for-dollar (cash withdrawals will reduce that a bit). As discussed thebanks will try to buy earning assets such as government bonds. The Fed andTreasury coordinate how many bonds will need to be sold by the two of them tooffer earning assets as alternatives to reserves, to allow the Fed to hit its interestrate target. A complication is that in the Treasury’s new issue market, itpursues “debt management”, offering a range of maturities. Occasionally theTreasury might offer a maturity that does not match “portfolio preferences” ofpotential purchasers.

Hugo: According to Vickrey, private capital in the U.S willhave trouble seeking profitable productive investment. Is government bond salesneeded as savings vehicles for the private sector to prevent assets bubbles?

A: Not sure I follow. To prevent asset bubbles, I’d userules, regulation, and supervision of financial institutions. The problemreally is not one of “excess saving”, so trying to “soak up” saving throughgovernment bond sales will not resolve it. If I want to speculate in Martianocean-front condo futures, I do not need any savings. All I need is a bank.

Kostas: “In reality, the Chinese receive Dollars(reserve credits at the Fed) from their export sales to the US (mostly), thenthey adjust their portfolios as they buy higher earning Dollar assets (mostly,Treasuries)”. It would be nice if you could elaborate on how foreigncentral banks get a hold of dollars in their Fed accounts. My understanding isthat this happens when central banks (of surplus countries) intervene inforeign exchange markets in order to maintain their currency foreign exchangevalue (by offering their currency in exchange for foreign assets). Is there anyother way for Bank of China to acquire US$ reserves?

–Dirk: Of course. The People’s Bank of China can borrow/buydollars from abroad. Not only from the US, but from anybody who holds dollars.In case of buying dollars, the counter-party has to accept yuan (not a problem)and the exchange rate might be changing (indeed a problem).

A: Thanks, Dirk, I think you answered.

Neil: “Recipients of government spending then can holdreceipts in the form of a bank deposit, can withdraw cash, or can use thedeposit to spend on goods, services, or assets.” Can’t they also swap itfor another currency with a willing party at an agreed exchange rate? So the ‘shifting of pockets’ surely has anexchange effect as well, not just an interest effect. Or do you see currencyexchange as just another asset purchase and that it will effect themacroeconomy in the same way as any other asset price shift?

A: Yes, I can use a dollar deposit to buy foreign stuff,take vacations abroad, or to buy foreign assets. The dollar deposit will beheld by someone else. My spending abroad can affect the exchange rate.

Andy: What effect,if any, does a reduction in bank depositshave on central banks’ day to day operations? For example if repayment ofprivate debt is greater than bank lending and fiscal tightening by governmentsat the same time.

A: Let us say bank deposits decline due to loan repayment. Whenit comes time to calculate reserve requirements (in the US, more than a monthlater), banks will find they have excess reserves relative to what is requiredon their deposits. They will attempt to individually reduce reserves held bypurchasing bonds (etc). That just shifts the reserves about. But it also pushesthe overnight interest rate down. The central bank responds with an open marketsale of treasuries. So it “forces” the hand of the central bank that reacts tothe interest rate decline.

Suspicious: When will we get the MMP explaining how to credibly regulate a bankingsector ? Banks have always managed to circumvent doctrines, ideologies,regulations, etc. and to wreck havoc the financial system. What’s the purposeof the central bank reserves not being inflationary if banks can loot it viacontrol fraud, and raise prices like in the commodities, and even causehyperinflation if only they were not as greedy as preventing anyone butthemselves to make money on it ?

Comments Off on Budget Deficits and Saving: Responses to Comments on Blog 21

Posted in MMP, Uncategorized

Tagged MMP

Does Obama’s Housing Plan Miss the Mark

William K. Black’s appearance on the Dylan Ratigan Show for Tuesday, October 25th. For those interested in cutting straight to the chase, Bill comes in around 2:30 min.

Comments Off on Does Obama’s Housing Plan Miss the Mark

Posted in Uncategorized, William K. Black

Tagged dylan ratigan, obama's housing plan, William K. Black

Europe’s Non-Solution

Today is supposedly the day where the problems of the euro zone get resolved once and for all. And when have we heard that before? Truth be told, it’s hard to get excited about any of the “solutions” on offer, because they steadfastly refuse to acknowledge that the eurozone’s problem is fundamentally one of flawed financial architecture. The banking “problems” and corresponding “need” for urgent recapitalization, are simply symptoms of that problem. Offering the “cure” of banking recapitalization for a problem which is ultimately one of national solvency (of which the banking crisis is but a symptom) is akin to offering chemotherapy to solve heart disease. Despite the current “thumbs-up” from the markets, the treatment is likely to exacerbate the disease, rather than represent the cure.

Let’s go back to core principles. We agree that the concern about Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain (PIIGS), indeed ALL other Euronations is justified. But using PIIGS countries as analogues to the US is a result of the failure of deficit critics to understand the differences between the monetary arrangements of sovereign and non-sovereign nations. Greece, Italy, France, and yes, Germany, are all USERS of the euro—not an issuer. In that respect, they are more like California, Massachusetts, indeed, any American state or Canadian province, all of which are users of their respective national government’s dollar.

But the eurozone’s chief policy makers continue to ignore this fundamental point and therefore, steadfastly avoid utilizing the one institution – the European Central Bank – which has the capacity to create unlimited euros, and therefore provides the only credible backstop to markets which continue to query the solvency of individual nation states within the euro zone. The ECB is so loath for everybody to agree on a Greek default, on the grounds that they bear “the loss” even though it is a notional accounting loss that has no bearing on their ability to create euros until the cows come home. By contrast, when you get national governments funding the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF), then it does ultimately threaten the credit ratings of France and Germany once the markets begin to call their bluff on how far they’re prepared to go to support this political fig-leaf called the EFSF. And because NONE of these countries is sovereign in respect to their currency (they USE the euro, but they don’t ISSUE it), it expands the potential insolvency problem, taking Germany down along with the rest.

The market pressures are most acute today in respect of Greece, but the broader concern is that speculators will eventually look toward the bigger PIIGS, such as Italy, and this is where the issue of the European Financial Stability Fund’s structural weaknesses come into play.

Let’s not get bogged down in numbers. The EFSF could have 440 billion euros behind, 1 trillion, 2 trillion, even 10 trillion euros, but it all comes back to the funding sources. The French are right: it makes no sense to implement this program without the backstop of the ECB, which is the only entity that could make any guarantees credible, by virtue of its ability to create unlimited quantities of euros.

Both the leading policy makers within the euro zone and market participants continue to conflate two distinct, but related issues: that of national solvency and insufficient aggregate demand. Policy makers want the ECB to do both, but in fact, the ECB is only required to deal with the solvency issue. When you do that in a credible way, then you get the capital markets re-opened and you give countries a better chance to fund themselves again via the capital markets. It means you do not actually need several trillion dollars, because you have a credible backstop in place – a central bank that can create literally trillions of euros via keyboard strokes and thereby address the markets’ concerns about national solvency. At this point, the bonds of the various nation states become less distressed and the corresponding need for massive banking recapitalization goes away.

Banking recapitalization is being demanded because the eurozone keeps demanding “voluntary” hair cuts” on Greek debt. But letting Greece default will not end Europe’s crisis and will not allow Germany and other core nations to brush themselves off and move merrily on their way. It becomes a question of whether a bailout now is good for Germany and France but not so good for Greece. Because if Greece is allowed to default, then their debt goes away. Authorities in effect agree substantially to lower their debt and reduce their payments.

How does that help the core countries, such as Germany or France? Indeed, getting France and Germany into the sovereign debt guarantee business via the EFSF (which is what happens if the ECB has no role) ultimately contaminates their own national “balance sheets”, thereby causing the markets to query their solvency as well and extending the contagion effects well beyond the PIIGS. We will have a situation akin to Ireland, whereby a country which had fundamentally solid government finances taken down via ill-considered guarantees to its insolvent banking system. Peripheral EMU is to core EMU as Irish banks once were to Ireland. By getting into the guarantee business, Ireland drove down a policy cul de sac from which it is still trying to extricate itself and smeared itself with correlated risk that required it to seek a bailout.

If the ECB continues to fund Greece via its bond purchases and does not allow them to default, then Greece has to continue to make these payments. But the ECB has this weird idea that somehow continuing their bond buying operation allows Greece (and other “fiscal deviants”) to avoid their “fiscal responsibilities” (i.e. continued fiscal austerity). The reality (however misguided), is that the bond buying operations actually provide the ECB with its leverage to force Greece and others to continue their “reforms”. Bond buying by the ECB changes the whole dynamic from doing Greece a favor to disciplining Greece by not allowing them to default and allowing the ECB to collect a significant income stream from the Greeks in the meantime. The minute Greece defaults, this leverage is lost. And then what is to stop the other “problem children” from demanding the same terms?

What is amazing as one listens to the commentary is the number of people who keep defining this as a banking crisis. Worse is their desire to punish the banks, which were told at the euro’s inception that one national bond was as good as another. The system wouldn’t have functioned (or, rather, its flaws would have become manifest sooner) if the national banks had proceeded on the basis that, say, Italian bonds weren’t as good as German bunds. So now the rules are being re-written and the “irresponsible” bankers are to be punished.

Okay, bankers have been irresponsible in a multitude of areas, many of which have already been documented on this blog. But here they are being punished for the wrong things. This is ultimately a national solvency crisis, not a banking crisis, so how does punishing the bankers and their shareholders help here?

Everybody in Europe, save the Germans, appears to understand this right now. Every time something unconventional is urged on the Germans, they scream “Weimar”. One of the indicators of development – intellectual and national and otherwise is to appreciate history and be able to decompose it into components.

Can’t the Germans make that simple division? I was a speaker at an EU forum two weeks with lots of Euro-types flown in. They kept talking about Weimar as if it was yesterday. Rome fell at one time too!

The other alternative is even less pleasant to contemplate, which is that there might be some Machiavellian genius behind the German position: perhaps their goal is to see the rest of Europe economically deflated into the ground, at which point, they will scoop up the pieces on the cheap, bit by bit. They’ll get their empire, albeit 70 years after Hitler expected when he invaded Poland. It’s Anschluss economics writ large. So Germany’s motives are either misguided, or more sinister than is now apparent.

But let’s deal with the core issue first: no solution can be found until the EMU leaders deal with the solvency issue. After that, everything else falls into place. It won’t restart economic growth, but it gets you out of the fiscal straitjacket because once the markets are persuaded that the individual countries are fundamentally solvent, they will lend again at sensible interest rates, which in turn can help to deal with today’s problem of insufficient aggregate demand.. And it means you don’t have to start worrying about massive haircuts on the debt because the bonds are trading at distressed levels precisely because the markets don’t believe these countries have a credible solution for the problem of national solvency.

The revenue sharing proposal which has been proposed by a number of us (see here and here ) is the most operationally efficient manner to involve the ECB, with a minimum of legal disruption. Additionally, it’s not inflationary, as it mere substitutes national bonds with reserves in the banking system and building banking reserves is not inflationary (see here for more)

Questions have been raised both about the ECB’s ultimate solvency and the legal constraints which govern its mandate. To deal with the solvency issue first: has anyone bothered to ask themselves what the concept of solvency means for a central bank that creates its own money? Bill Mitchell has addressed this many times (see here), but if one takes the 30 seconds required to ponder this question, surely we can understand that the concept of solvency is totally and thoroughly irrelevant to a central bank with a sovereign currency (i.e. not convertible on demand into a fixed quantity of other currencies or a commodity).

The ECB and others who resist its involvement in the salvation of the common currency continue to think and act as if it is a central bank operating under a gold standard. That is insane, and certifiably so.

In regard to the legal requirements:

- The ECB does not have a statutory minimum capital requirement.

- It transfers profits to national governments but in times of losses is can only request a capital injection should its capital be depleted.

- The European Council (which is representative of elected governments) is not compelled to accede to this request.

- Hence, the ECB is a perfect balance sheet to warehouse risk since its losses need not become fiscal transfer as it can rebuild its profits via seigniorage over a number of yrs. In that sense, its role is analogous to that of the Swiss National Bank effectively warehoused its Swiss banks’ bad paper during the height of the crisis in 2008.

Of course, the ECB would HATE this and the risk is that its losses would limit its willingness to maintain its bond buying program. But it remains the only game in town. The bond buying is precisely what gives them leverage and, paradoxically, preserves the quality of its balance sheet, since the purchases themselves ensure that the distressed bonds of countries such as Greece do not lose value because the ECB prevents them from defaulting. As we have described before, the ECB effectively uses the income of the Greeks (and others) to rebuild its capital base. The minute the EFSF is introduced, along with the notion of haircuts, the ECB loses its leverage and the credit risk contagion shifts to the core countries of the EU, which WILL threaten their AAA ratings.

It also means this whole issue of banking recapitalisation is a big red herring. In reality, banks don’t really need recapitalisation. What most depositors care about is being able to get their deposit money out of their bank, so whether they are solvent or not is not their primary concern. Arguably, all of the US banks were insolvent in 1982, but the FDIC guarantees worked to stabilise the system.

Bank capital is always available at a price. The ‘market process’ is for net interest margins to widen to the point where earnings attract capital. Except this all assumes credit worthiness isn’t an issue.

The problem with current policy is that it is turning both the public and private sector into a ‘credit event’ which will make it extremely difficult for the borrowers to switch lenders.

In the current environment you have a solvency crisis which is feeding into the banking system because a large proportion of their assets are euro denominated government bonds. Going down the path of “voluntary” hair cuts and forced recapitalization will simply set off a massive debt deflation spiral. We will see bank’s fire selling assets left and right – management will not issue equity at these miserably low price to book values. Which in turn will depress economic activity even further, widen the very public deficits which are so exorcising the Eurozone’s policy making elite, and bring us back to Square One. Already the guns are being turned on Italy, now that Greece is on the threshold of being “solved”.

In the words of Italy’s greatest poet: “Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’entrate.”*

*Abandon hope all ye who enter here – Dante, ‘The Inferno’

Comments Off on Europe’s Non-Solution

Posted in Marshall Auerback, Uncategorized

Tagged ECB, Eurozone, greek economy, Marshall Auerback, piigs