First Published on New Deal 2.0.

Do the Chinese really fund our deficit? Or is this more Neo-classical money mythology?

Another Presidential junket to Asia and another one of the usual lectures from China, decrying our “profligate ways”. Today’s Wall Street Journal reports:, “China’s top banking regulator issued a sharp critique of U.S. financial management only hours before President Barack Obama commenced his first visit to the Asian giant, highlighting economic and trade tensions that threaten to overshadow the trip.”

According to Liu Mingkang, chairman of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, a weak U.S. dollar and low U.S. interest rates had led to “massive speculation” that was inflating asset bubbles around the world. It has created “unavoidable risks for the recovery of the global economy, especially emerging economies,” Mr. Liu said. The situation is “seriously impacting global asset prices and encouraging speculation in stock and property markets.”

Well, “them’s fightin’ words”, as we say over here. And of course, the President and his advisors are supposed to accept this criticism mildly because in the words of the NY Times, the US has assumed “the role of profligate spender coming to pay his respects to his banker.”

The Times actually does believe this to be true. They refer to China’s role as America’s largest “creditor” as a “stark fact”. They do not seem to understand that simply because a country issuing debt which it creates, it does not depend on bond holders to “fund” anything. Bonds are simply a savings alternative to cash offered by the monetary authorities, as we shall seek to illustrate below.

It is less clear to us whether the Chinese actually believe this guff, or simply articulate it for public consumption. China has made a choice: for a variety of reasons, it has adopted an export-oriented growth strategy, and largely achieved this through closely managing its currency, the remnimbi, against the dollar.

One can query the choice, as many would argue that it is more economically and socially desirable for China to consume its own economic output. According to Professor Bill Mitchell, for example, “once the Chinese citizens rise up and demand more access to their own resources instead of flogging them off to the rest of the world…then the game will be up. They will stop accumulating financial assets in our currencies and we will find it harder to run [current account deficits] against them.”

But there have undoubtedly been certain benefits that have accrued to the Chinese as a consequence of this strategy. The export prices obtained by Chinese manufacturers are about 10 times as high as the prices obtained in the more competitive domestic markets, and the challenge of competing in global markets has forced Chinese manufacturers to adhere to higher quality standards. This, in turn, has improved the overall quality of Chinese products. In the words of James Galbraith:

“Is there a way for the Chinese manufacturing firm to turn a profit? Yes: the alternative to selling on the domestic market is to export. And export prices, even those paid at wholesale, must be multiples of those obtained at home. But the export market, however vast, is not unlimited, and it demands standards of quality that are not easily obtained by neophyte producers and would not ordinarily be demanded by Chinese consumers. Only a small fraction of Chinese firms can actually meet the standards. These standards must be learned and acquired by practice.” (”The Predator State, Ch. 6, “There is no such thing as free trade”, pg. 84).

What about the US government? What should it do? Should it actually respond to China’s complaints by trying to “defend the dollar”?

I hear this recommendation all of the time in the chatterplace of the financial markets, but seldom do those who fret about the dollar’s declining level actually suggest a concrete strategy to achieve the objective. In fact, it is unclear to me that there is any measure the Fed or Treasury could adopt which might support the dollar’s external value.

And why should they? Given the horrendous unemployment data, and 65% capacity utilization, it is hard to view imported inflationary pressures via a weaker dollar actually becoming a serious threat.

But wait? Don’t the Chinese (and other external creditors) “fund” our deficit? And won’t they demand a higher equilibrating interest rate in order to offset the declining value of their Treasury hoard?

Again, this displays a seriously lagging understanding of how much modern money has changed since Nixon changed finance forever by closing the Gold window in 1973. Now that we’re off the gold standard, the Chinese, and other Treasury buyers, do not “fund” anything, contrary to the completely false & misguided scare stories one reads almost daily in the press.

This claim is seldom challenged, but our friend, Warren Mosler, recently gave an excellent illustration of this fact in an interview with Mike Norman. Mosler provides a hypothetical example in which China decides to sell us a billion dollars’ worth of T-shirts. We buy a billion dollars’ worth of T-shirts from China:

“And the way we pay them is somebody pays China. And the money goes into their checking account at the Federal Reserve. Now, it’s called a reserve account because it’s the Federal Reserve, and they give it a fancy name. But it’s a checking account. So we get the T-shirts, and China gets $1 billion in their checking account. And that’s just a data entry. That’s just a one and some zeroes.

Whoever bought them gets a debit. You know, it might have been Disneyland or something. So we debit Disney’s account and then we credit China’s account.

In this situation, we’ve increased our trade deficit by $1 billion. But it’s not an imbalance. China would rather have the money than the T-shirts, or they wouldn’t have sent them. It’s voluntary. We’d rather have the T-shirts than the money, or we wouldn’t have bought them. It’s voluntary. So, when you just look at the numbers and say there’s a trade deficit, and it’s an imbalance, that’s not correct. That’s imbalance. It’s markets. That’s where all market participants are happy. Markets are cleared at that price.

Okay, so now China has two choices with what they can do with the money in their checking account. They could spend it, in which case we wouldn’t have a trade deficit, or they can put it in another account at the Federal Reserve called a Treasury security, which is nothing more than a savings account. You give them money, you get it back with interest. If it’s a bank, you give them money, you get it back with interest. That’s what a savings account is.”

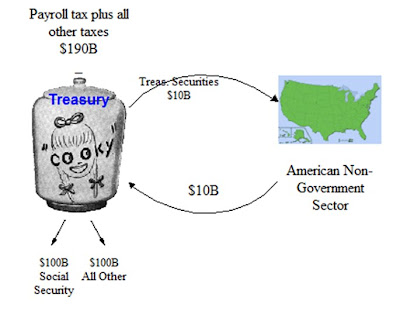

The example here clearly illustrates that bonds are a savings alternative which we offer to the Chinese manufacturer, not something which actually “funds” our government’s spending choices. It demonstrates that rates are exogenously determined by our central bank, not endogenously determined by the Chinese manufacturer who chooses to park his dollars in treasuries (credit demand, by contrast, is endogenous).

Here is how the mechanics actually work: government spending and lending adds reserves to the banking system because when the government spends, it electronically credits bank accounts.

By contrast, government taxing and security sales (i.e. sales of bonds) drain (subtract) reserves from the banking system. So when the government realizes a budget deficit (as is the case today), there is a net reserve add to the banking system, WHICH BRINGS RATES LOWER (not higher). That is, government deficit spending results in net credits to member bank reserves accounts. If these net credits lead to excess reserve positions, overnight interest rates will be bid down by the member banks with excess reserves to the interest rate paid on reserves by the central bank (currently .25% in the case of the US since the Fed started to pay interest on these reserves). If the central bank has a positive target for the overnight lending rate, either the central bank must pay interest on reserves or otherwise provide an interest bearing alternative to non interest bearing reserve accounts. But this is a choice determined by our central bank, not an external creditor.

Yet we are constantly being told by the financial press that the dollar’s weakness was supposed be the factor that would “force” the Fed to raise rates, since the Chinese supposedly “fund” our deficits.

So far, that thesis hasn’t been borne out. And it won’t be, because this isn’t how things operate in a post gold-standard world.

And a second and equally salient point: what would those who fret about the dollar, have the Fed do? Should they raise rates to defend it? It is unclear that this would work. The relationship between a given level of interest rates offered by the central bank and the external value of a currency is tenuous. Consider Japan as Exhibit A. The BOJ has been offering virtually free money for 15 years and yet the yen today remains a strong currency (much to the chagrin of the likes of Toyota or Sony).

Of course, higher rates can have an offsetting beneficial income impact (what Bernanke calls the “fiscal channel”), but it does not follow that a decision to raise rates would actually elevate the value of the dollar (and the benefits of higher rates from an income perspective could just as easily be achieved via lower taxation).

The reality is that private market participants could well view the move as something akin to a panicked response by the Fed, and the decision could well trigger additional capital flight, which could weaken the value of the dollar.

So it is unclear to me what the Tsy or Fed should be doing about the dollar. My view is that this is a private portfolio preference shift and I don’t think central banks should be responding to every vicissitude of changing market preferences. The US government should simply ignore the market chatter and idle threats from the Chinese and do nothing.