The Buckaroo Program

In the United States, there is a growing movement on college campuses to increase student involvement in their communities, particularly through what is known as “service-learning” in which students participate in community service activities organized by local community groups. It should become obvious that a modern monetary economy that adopts the full employment program described here will operate much like our community service hours program.

We have chosen to design our program as a “monetary” system, creating paper notes, “buckaroos” (after the UMKC mascot, a kangaroo), with the inscription “this note represents one hour of community service by a UMKC student”, and denominated as “one roo hour”. Each student is required to pay B25 to the UMKC “Treasury” each semester. Approved community service providers (state and local government offices, university offices, public school districts, and not-for-profit agencies) submit bids for student service hours to the Treasury, which “awards” special drawing rights (SDRs) to the providers so long as basic health, safety, and liability standards are met. The providers then draw on their SDRs as needed pay students B1 per hour worked. This is equivalent to “spending” by the UMKC treasury. Students then pay their taxes with buckaroos, retiring Treasury liabilities.

Several implications are immediately obvious. First, the UMKC treasury cannot collect any buckaroo taxes until it has spent some buckaroos. Second, the Treasury cannot collect more buckaroos in payment of taxes than it has previously spent. This means that the “best” the Treasury can hope for is a “balanced budget”. Actually, it is almost certain that the Treasury will run a deficit as some buckaroos are “lost in the wash” or hoarded for future years. While it is possible that the Treasury could run a surplus in future years, this would be limited by the quantity of previously hoarded buckaroos that could be used to pay taxes. Third, and most important, it should be obvious that the Treasury faces no “financial constraints” on its ability to spend buckaroos. Indeed, the quantity of buckaroos provided is “market demand determined”, by the students who desire to work to obtain buckaroos and by the providers who need student labor. Furthermore, it should be obvious that the Treasury’s spending doesn’t depend on its tax receipts. To drive the point home, we can assume that the Treasury always burns every buckaroo received in payment of taxes. In other words, the Treasury does not impose taxes in order to ensure that buckaroos flow into its coffers, but rather to ensure that student labor flows into community service. More generally, the Treasury’s budget balance or imbalance doesn’t provide any useful information to UMKC regarding the program’s success or failure. A Treasury deficit, surplus, or balance provides useless accounting data.

Note that each student has to obtain a sufficient number of buckaroos to meet her tax liability. Obviously, an individual might choose to earn, say, B35 in one semester, holding B10 as a hoard after paying the B25 tax for that semester. The hoards, of course, are by definition equal to the Treasury’s deficit. UMKC has decided to encourage “thrift” by selling interest-earning buckaroo “bonds”, purchased by students with excess buckaroo hoards. This is usually described as government “borrowing”, thought to be necessitated by government deficits. Note however, that the Treasury does not “need” to borrow its own buckaroos in order to deficit spend—no matter how high the deficit, the Treasury can always issue new buckaroos. Indeed, the Treasury can only “borrow” buckaroos that it has already spent, in fact, that it has “deficit spent”. Finally, note that the Treasury can pay any interest rate it wishes, because it does not “need” to “borrow” from students. For this reason, Treasury bonds should be seen as an “interest rate maintenance account” designed to keep the base rate at the Treasury’s target interest rate. Without such an account, the “natural base interest rate” is zero for buckaroo hoards created through deficit spending. Note that no matter how much the Treasury spends the base rate would never rise above zero unless the Treasury offers positive interest rates; in other words, Treasury deficits do not place any pressure on interest rates.

What determines the value of buckaroos? From the perspective of the student, the “cost” of a buckaroo is the hour of labor that must be provided; from the perspective of the community service provider, a buckaroo buys an hour of student labor. So, on average, the buckaroo is worth an hour of labor—more specifically, an hour of average student labor. Note that we can determine the value of the buckaroo without reference to the quantity of buckaroos issued by the Treasury. Whether the Treasury spends a hundred thousand buckaroos a year, or a million a year, the value is determined by what students must do to obtain them.

The Treasury’s deficit each semester is equal to the “extra” demand for buckaroos coming from students; indeed, it is the “extra” demand that determines the size of the Treasury’s deficit. We might call this “net saving” of buckaroos, and it is equal—by definition—to the Treasury’s deficit over the same period. What if the Treasury decided it did not want to run deficits, and so proposed to limit the total number of buckaroos spent in order to balance the budget? In this case, it is almost certain that some students would be unable to meet their tax liability. Unlucky, procrastinating students would find it impossible to find a community service job, thus would find themselves “unemployed” and would be forced to borrow, beg, or steal buckaroos to meet their tax liabilities. Of course, any objective analysis would find the source of the unemployment in the Treasury’s policy, and not in the characteristics of the unemployed. Unemployment at the aggregate level is caused by insufficient Treasury spending.

Some of thisanalysis applies directly to our economic system as it actually operates, while some of it would apply to the operation of our system if it were to adopt a full employment program. Let us examine the operation of a modern money system.

Modern Monetary Systems

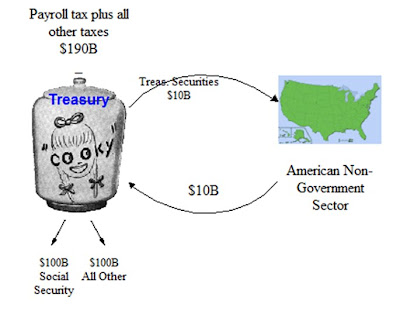

In all modern economies, money is a creature of the State. The State defines money as that which it accepts at public pay offices (mainly, in payment of taxes). Taxes create a demand for money, and government spending provides the supply, just as our buckaroo tax creates a demand for buckaroos, while spending by the Treasury provides the supply. The government does not “need” the public’s money in order to spend; rather, the public needs the government’s money in order to pay taxes. This means that the government can buy whatever is for sale in terms of its money merely by providing it.

Because the public will normally wish to hold some extra money, the government will normally have to spend more than it taxes; in other words, the normal requirement is for a government deficit, just as the UMKC Treasury always runs a deficit. Government deficits do not require “borrowing” by the government (bond sales), rather, the government provides bonds to allow the public to hold interest-bearing alternatives to non-interest-bearing government money. Further, markets cannot dictate to government the interest rate it must pay on its debt, rather, the government determines the interest rate it will pay as an alternative to non-interest-earning government money. This stands conventional analysis on its head: fiscal policy is the primary determinant of the quantity of money issued, while monetary policy primarily has to do with maintaining positive interest rates through bond sales—at the interest rate the government chooses.

In summary, governments issue money to buy what they need; they tax to generate a demand for that money; and then they accept the same money in payment of the tax. If a deficit results, that just lets the population hoard some of the money. If the government wants to, it can let the population trade the money for interest earning bonds, but the government never needs to borrow its own money from the public.

This does not mean that the deficit cannot be too big, that is, inflationary; it can also be too small, that is deflationary. When the deficit is too small, unemployment results (just as it results at UMKC when the Treasury’s spending of buckaroos is too small). The fear, of course, is that government deficits might generate inflation before full employment can be reached. In the next section we describe a proposal that can achieve full employment while actually enhancing price stability.

Public Service Employment and Full Employment with Price and Currency Stability

Very generally, the idea behind our proposal is that the national government provides funding for a program that guarantees a job offer for anyone who is ready, willing and able to work. We call this the Public Service Employment program, or PSE. What is the PSE program? What do we want to get out of it?

1. It should offer a job to anyone who is ready, willing and able to work; regardless of race or gender, regardless of education, regardless of work experience; regardless of immigration status; regardless of the performance of the economy. Just listing those conditions makes it clear why private firms cannot possibly offer an infinitely elastic demand for labor. The government must play a role. At a minimum, the national government must provide the wages and benefits for the program, although this does not actually mean that PSE must be a government-run program.

2. We want PSE to hire off the bottom. It is an employment safety net. We do not want it to compete with the private sector or even with non-PSE employment in the public sector. It is not a program that operates by “priming the pump”, that is, by raising aggregate demand. Trying to get to full employment simply by priming the pump with military spending could generate inflation. That is because military Keynesianism hires off the top. But by definition, PSE hires off the bottom; it is a bufferstock policy—and like any bufferstock program, it must stabilize the price of the bufferstock—in this case, wages at the bottom.

3. We want full employment, but with loose labor markets. This is virtually guaranteed if PSE hires off the bottom. With PSE, labor markets are loose because there is always a pool of labor available to be hired out of PSE and into private firms. Right now, loose labor markets can only be maintained by keeping people out of work—the old reserve army of the unemployed approach.

6. Finally, we want PSE workers to do something useful. For the U.S.A. we have proposed that they focus on provision of public services, however, a developing nation may have much greater need for public infrastructure; for roads, public utilities, health services, education. PSE workers should do something useful, but they should not do things that are already being done, and especially should not compete with the private sector.

These six features pretty well determine what a PSE program ought to look like. This still leaves a lot of issues to be examined. Who should administer the program? Who should do the hiring and supervision of workers? Who should decide exactly what workers will do? There are different models consistent with this general framework, and different nations might take different approaches. Elsewhere (Wray 1998, 1999) I have discussed the outlines of a program designed specifically for the USA. Very briefly, I suggest that given political realities in the USA, it is best to decentralize the program as much as possible. State and local governments, school districts, and non-profit organizations would be allowed to hire as many PSE workers as they could supervise. The federal government would provide the basic wage and benefit package, while the hiring agencies would provide supervision and capital required by workers (some federal subsidy of these expenses might be allowed). All created jobs would be expected to increase employability of the PSE workers (by providing training, experience, work records); PSE employers would compete for PSE workers, helping to achieve this goal. No PSE employer would be allowed to use PSE workers to substitute for existing employees (representatives of labor should sit on all administrative boards that make hiring decisions). Payments by the federal government would be made directly to PSE workers (using, for example, Social Security numbers) to reduce potential for fraud.

Note that some countries might choose a much higher level of centralization. In other words, program decentralization is dictated purely by pragmatic and political considerations. The only essential feature is that funding must come from the national government, that is, from the issuer of the currency.

Before concluding, let us quickly address some general questions. First, many people wonder about the cost—can we afford full employment? To answer this, we must distinguish between real costs and financial expenditures. Unemployment has a real cost—the output that is lost when some of the labor force is involuntarily unemployed, the burdens placed on workers who must produce output to be consumed by the unemployed, the suffering of the unemployed, and social ills generated by unemployment and poverty. From this perspective, providing jobs for the unemployed will reduce real costs and generate net real benefits for society. Indeed, it is best to argue that society cannot afford unemployment, rather than to suppose that it cannot afford employment!

On the other hand, most people are probably concerned with the financial cost of full employment, or, more specifically, with the impact on the government’s budget. How will the government pay for the program? It will write checks just as it does for any other program. (See Wray 1998.) This is why it is so important to understand how the modern money system works. Any nation that issues its own currency can financially afford to hire the unemployed. A deficit will result only if the population desires to save in the form of government-issued money. In other words, just as in UMKC’s buckaroo program, the size of the deficit will be “market demand” determined by the population’s desired net saving.

Economists usually fear that providing jobs to people who want to work will cause inflation. Thus, it is necessary to explain how our proposed program will actually contribute to wage stability, promoting price stability. The key is that our program is designed to operate like a “buffer stock” program, in which the buffer stock commodity is sold when there is upward pressure on its price, or bought when there are deflationary pressures. Our proposal is to use labor as the buffer stock commodity, and as is the case with any buffer stock commodity, the program will stabilize the commodity’s price. The government’s spending on the program is based on a “fixed price/floating quantity” model, hence, cannot contribute to inflation.

Note that the government’s spending on the full employment program will fluctuate countercyclically. When the private sector reduces spending, it lays-off workers who then flow into the bufferstock pool, working in the full employment program. This automatically increases total government spending, but not prices because the wage paid is fixed. As the quantity of workers hired at the fixed wage rises, this results in a budget deficit. On the other hand, when the private sector expands, it pulls workers out of the bufferstock pool, shrinking government spending and thus reducing deficits. This is a powerful automatic stabilizer that operates to ensure the government’s spending is at just the right level to maintain full employment without generating inflation.

REFERENCES

Wray, L. Randall. 1998. Understanding Modern Money: the key to full employment and price stability, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

—–. 1999. “Public Service Employment—Assured Jobs Program: further considerations“, Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 483-490.