By J.D. Alt

Commentary on part 2, again, was extremely helpful and much appreciated. Especially useful were suggestions from readers who “didn’t recognize” my description of the Boomers ideological obsession. This got me to substantially rethink the framing, and I hope that is now fixed. What I realized—and looking back on my own experience, it seems obvious in retrospect—was that what the Boomers were focused on had little to do with the idea of “competition” and much to do with rebelling against (and distrusting) institutional power—especially the institutional power of the federal government. It became natural for them to want to starve that government to keep it from interfering with the individualism the Boomers championed. As I said in my comment to the post, “Do your own thing” seems to have morphed seamlessly into the “trickle-down” economics of federal austerity.

Draft of the next section is as follows:

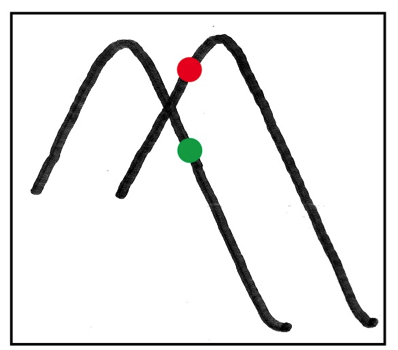

The squiggle illustrated here may look like the Ebola virus, but it isn’t. The resemblance is just an eerie coincidence. It’s actually a graphical snapshot of the classic “Predator-Prey Model.” This mathematical exercise, first developed in the 1920s, serves as the introductory basis for a more recent NASA funded effort which produced—amidst a brief flurry of news and commentary last spring—the startling conclusion that a complete collapse of modern civilization may now be “irreversible.”

The squiggle illustrated here may look like the Ebola virus, but it isn’t. The resemblance is just an eerie coincidence. It’s actually a graphical snapshot of the classic “Predator-Prey Model.” This mathematical exercise, first developed in the 1920s, serves as the introductory basis for a more recent NASA funded effort which produced—amidst a brief flurry of news and commentary last spring—the startling conclusion that a complete collapse of modern civilization may now be “irreversible.”