By Felipe Rezende

Part IV

This last part of the series (see Part I, II, and III here, here and here) will focus on the Brazilian response to the crisis.

What Should Brazil do?

The Brazilian current crisis fit with Minsky’s theory of instability (see here, here and here). The traditional response to a Minsky crisis involves government deficits to allow the non-government sector to net save. That is, if the private sector desire to net save increases, then fiscal deficits increase to allow it to accumulate net financial assets. The sharp increase in budget deficits in 2015 comes as no surprise. Rezende (2015a) simulated

“a scenario in which we have rising government deficits to offset current account deficits, to allow the domestic private sector balance to generate financial surpluses. In this case, in the presence of current account deficits equal to 4% of GDP, to allow the private sector to net save 2% of GDP, it would require government deficits equal to 6% of GDP. If the private sector is going to save 5% of GDP (equal to the 2002-2007 average pre-crisis) and a current account deficit equal to 4% of GDP then we must have an overall government budget in deficit equal to 9% of GDP. Given the current state of affairs, government deficits of this magnitude might be politically unfeasible right now. (Rezende (2015a)

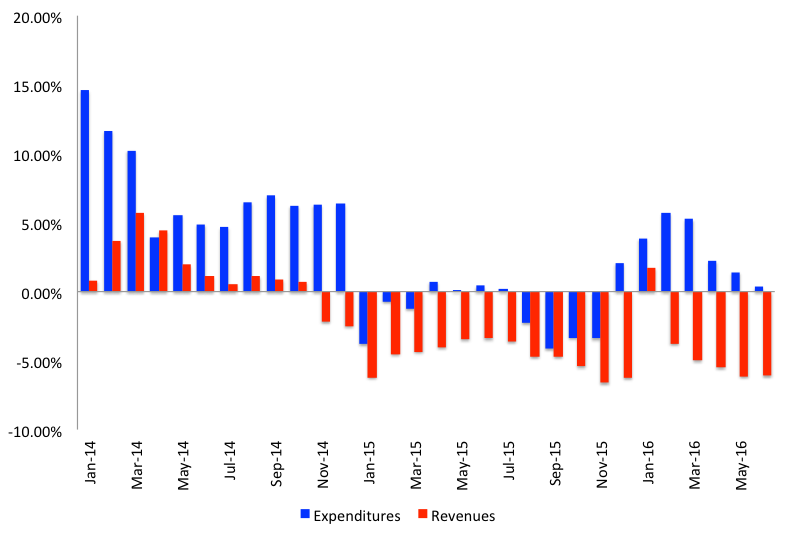

In 2015, Brazil’s budget deficit increased from 2% of GDP in 2008 to 10.38% of GDP in 2015. Though government deficits support incomes (cash flow and portfolio effects) and stabilizes profits, the bad composition of government budget, that is, virtually the entire deficit is due to interest payments, did little to sustain employment. Brazil’s primary budget balance swung from a surplus of 3% of GDP over a decade to a deficit. As this happened, credit rating agencies’ decision to downgrade Brazil’s sovereign debt to junk status put Ms. Rousseff under growing pressure to cut public spending. In this regard, with the implementation of austerity policies in 2015 automatic stabilizers were switched off, that is, the real growth (deflated by IPCA) of expenses by the central government sharply declined (figure 1) aggravating the recession.

Figure 1. Real Growth (deflated by IPCA) of Revenues and Expenses of the Central Government, Year to Date Growth

Source: Tesouro Nacional

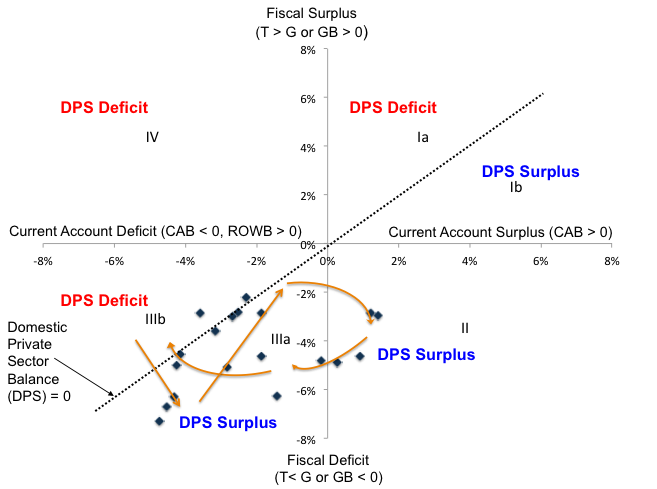

While Brazil’s credit rating cut to junk increased firms’ funding costs making international financial obligations more costly for local firms, these circumstances were exacerbated by a reversal of favorable external conditions and a deterioration of domestic factors including a premature withdrawal of stimulus that led to poor performance by the Brazilian economy and created an opening for critics of Brazilian economic policy who characterized it as too interventionist. This affected the Brazilian political process and led to a change in Brazilian policy in the direction of austerity. The response was based on the traditional approach (structural adjustment policies) grounded on the “Washington Consensus” to constrain domestic demand and keep imports down through the imposition of fiscal austerity and tight monetary policy (figure 2). By reducing the domestic absorption, it undermines domestic activity and creates unemployment. The result was obvious, fiscal deficits and government debt kept rising and incomes, employment, and production collapsed.

Figure 2. A Minsky Crisis and “Washington Consensus” Crisis (1995-2013 average)

Source: author’s elaboration

As discussed in the previous posts, the Brazilian economy is trapped in a vicious dynamic cycle moving from quadrants: IIIa è II è IIIa è IIIb è IIIa. This is the result of endogenous process, which combined with the reliance on external financing, high interest rates designed to attract international investors and fight inflation led to an overvalued currency, damaging the competiveness of domestic industries and its export capacity. The reliance on capital flows not only failed to increase productive investment (Bastos et al 2015), but it produced rising external private indebtedness and chronic current account deficits. That is, the reliance on capital flows as a source of development finance has led to the real appreciation of the currency, rising foreign capital inflows, rising external private indebtedness, chronic current account deficits, and increased exchange rate volatility. The more successful in attracting capital flows and generating returns, the more fragile will be the current account position (chronic current account deficits). That is, as the economy grows, it exposes the limits to external finance and the endemic financial fragility created by the success of domestic stabilization policies and it produces a structural influence on the composition of payment flows and the country’s export capacity.

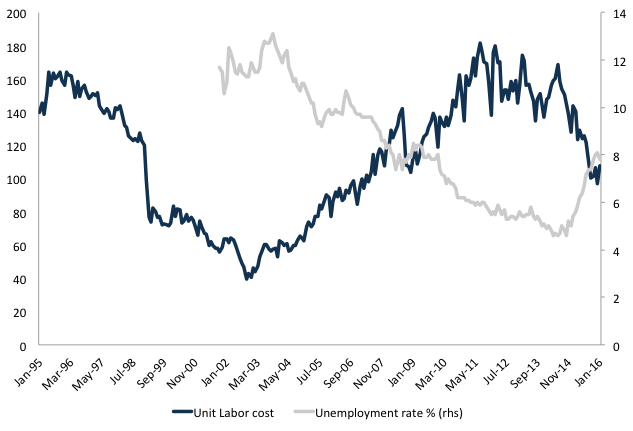

As this happens, the economy tends to move toward current account deficits, which generates an “external drag”—that removes aggregate profits of firms. It has already being suggested that the limits to external finance is given by the Domar’s condition (Kregel 2004, 2009), that is, capital flows should increase at a rate at least equal to the rate of interest paid on the foreign lending. The Domar’s condition is similar to a Ponzi scheme, which is inherently unstable. In this regard, Brazil’s current crisis is resembles a “Washington Consensus crisis”, that is, the attempt to impose structural adjustment policies, forcing a substantial decline in domestic absorption and real wages resulting in an increase in unemployment (figure 3). Even though Brazil’s current crisis is not really a financial sector crisis, Brazilian security prices were impacted generating rising interest rates on Brazilian debt and the collapse in the value of Brazilian debt in investors’ portfolios. A Minskyan policy response would have required the central bank’s action to support asset prices, however, the central bank decided not to act. Only the Treasury intervened occasionally to stabilize securities prices (see Ministry of Finance 2016).

Figure 3. Unit Labor cost (ULC-US$ – June/1994=100) and the unemployment rate

Source: BCB

The Policy Implications

In spite of overwhelming evidence that austerity policies failed where it was implemented, it is ironic that mainstream economists in Brazil have proposed fiscal austerity to pave the way for economic growth. In Brazil, there is a virtual consensus towards fiscal tightening. The most likely scenario is that Brazil will continue to run current account deficits in the foreseeable future, say equal to the post crisis average equal to 2% of GDP.

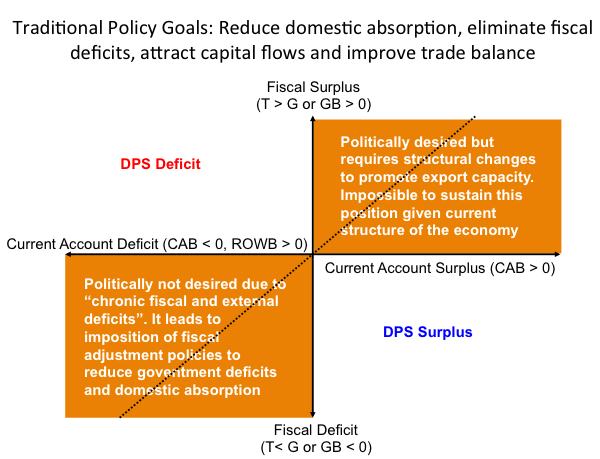

If policymakers narrow the nominal budget deficit to zero in the next administration (Fraga 2016) then the private sector must run a deficit equal to 2% of GDP (equal to the current account deficit). However, as already discussed, the private sector deficit (spending more than its income) is unsustainable and dangerous to macroeconomic stability. If the domestic private sector wants to run a surplus (spending less than its income) then the government balance must be above the current account deficit (figure 4).

Figure 4. Sectorial financial balances and traditional policy goals

The policies proposed by fiscal hawks fail to recognize the risks: fiscal austerity poses the danger of recession and even default by indebted households and business. Moreover, contrary to the conventional view, there is no reason to believe that cutting public spending will automatically increase private spending. To be sure, an attempt to impose fiscal austerity has already led to further declines in output, employment, and private spending, thus amplifying the direct effects of government cutbacks and limiting the ability of businesses and households to generate strong cash flows to service their financial obligations, stimulate production and create employment.

Policymakers and market pundits must understand that one sector’s financial position cannot be viewed in isolation. They must realize the links between public sector deficits, domestic private sector surpluses, and current account deficits. This is not to say that Brazil should run fiscal deficits forever nor that they cannot be inflationary but following fiscal rules blindly without determining the impacts on the private sector balance can be dangerous to growth and stability.

Unfortunately, much of the concern about public finance in Brazil centers around reducing the public debt burden and debt sustainability. However, a sovereign government, which issues its non-convertible currency, is not subject to the same constraints that business, local states, and households face (Rezende 2009). The Brazilian government issues its own currency, the Real, and has the power to levy and collect taxes denominated on its liability. Brazil’s government necessarily spends first and then collects taxes, spends first and then “borrows” back the Reais it just spent. As in the case of other sovereign countries, it can always service its debt denominated in its currency.

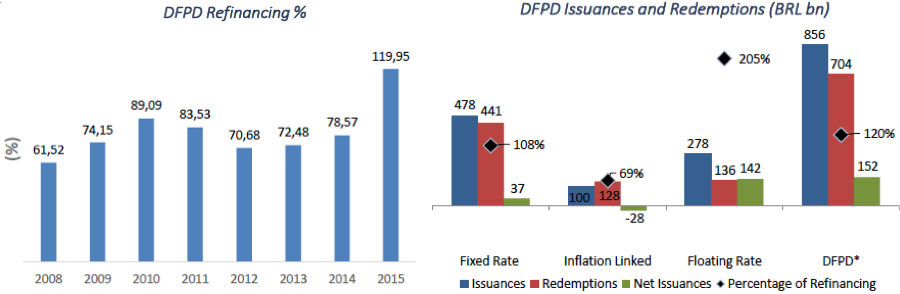

However, Brazilian policymakers feared the news of a credit rating downgrade, in particular in an election year. They have been operating under the wrong paradigm. Counter to the deficit hysteria view, affordability isn’t an issue because the federal government can always meet their debt obligations denominated in their own currency. Ratings agencies are still clueless on their assessment of default risks of sovereign currency issuing governments (see here, here, and here). Contrary to the conventional view, in spite of credit downgrades and growing public debt demand for government securities in 2015 was the highest in 8 years (figure 5)!

Figure 5. Domestic federal public debt (DFPD) refinancing; issuances and redemptions in 2015

Source: Ministry of Finance 2016

Recent CRAs warnings and downgrades on Brazil’s sovereign credit rating miss the point that Brazil has attained monetary sovereignty. It is the sole issuer of a nonconvertible currency (Reais). It cannot be forced by currency users to default on its domestic debt denominated in local currency.

Are there policy alternatives?

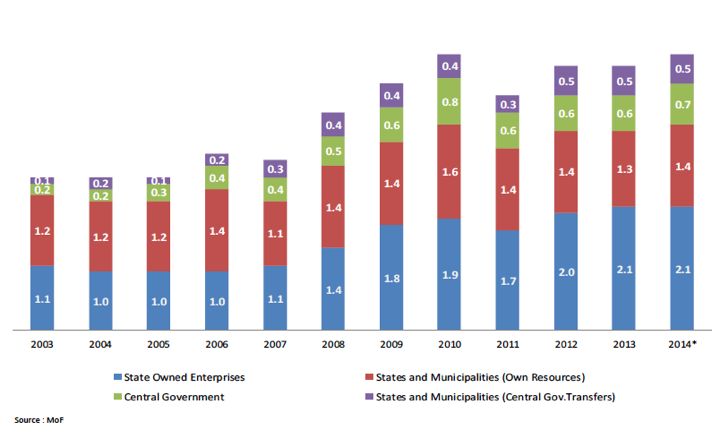

Brazil needs to effectively make the transition to a development strategy based on domestic demand from dependence from foreign demand and finance. Even though Brazil had a transition policy in place primarily based on public investment, the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC I and II) and a broad program of concessions, it is struggling to shift its development strategy to foster domestic demand growth from one designed to attract external capital and build on external demand. The Growth Acceleration Program (PAC I and II) notwithstanding, Brazil’s federal public investment public investment is unusually low given Brazil’s infrastructure bottlenecks and investment needs (figure 6 and 7).

Figure 6. Public Investment (% of GDP)

Source: Ministry of Finance 2016a.

There is ample policy space to promote private and public infrastructure investment, in which public banks – in particular Brazil’s national development bank (BNDES) – and private domestic capital markets should play a major role financing the supply side of this program.

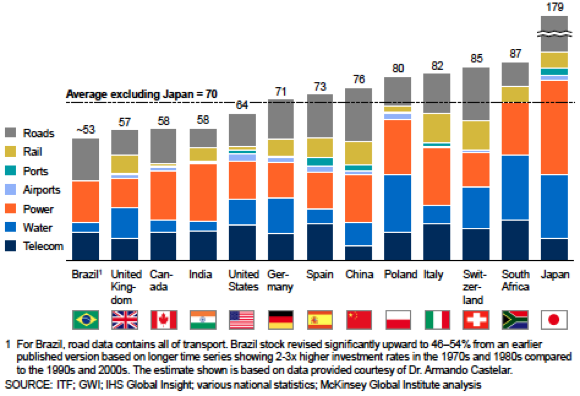

It is well known that government spending can contribute to productivity lowering private sector costs and through investment in key areas such as infrastructure, health and education, and research and development. Brazil needs to shifts its policy to mobilize domestic resources and adopt an investment-oriented growth strategy. There is ample space for policy to promote infrastructure investment (public and private in Brazil (figure 7). For instance, the world economic forum ranks Brazil’s infrastructure 114th out of 148 countries (WEF 2013). Even the IMF is calling for an infrastructure push by developing economies (see IMF 2015a).

Figure 7. Total infrastructure stock (% of GDP)

Source: Mckinsey 2013, p. 13

It is crucial to increase government-sponsored infrastructure investment projects as the current rate of federal investment in infrastructure is small compared to Brazil’s investment needs. Brazil is well known for its high tax burden. It should use the fiscal powers of the federal government to increase government deficit on both fronts, that is, increasing federal government investment in infrastructure and tax cuts for households and firms by simplifying its tax system and providing tax cuts on production, employment, and income. It can close Brazil’s housing gap by 2018 through the expansion of the government program My home, My life.

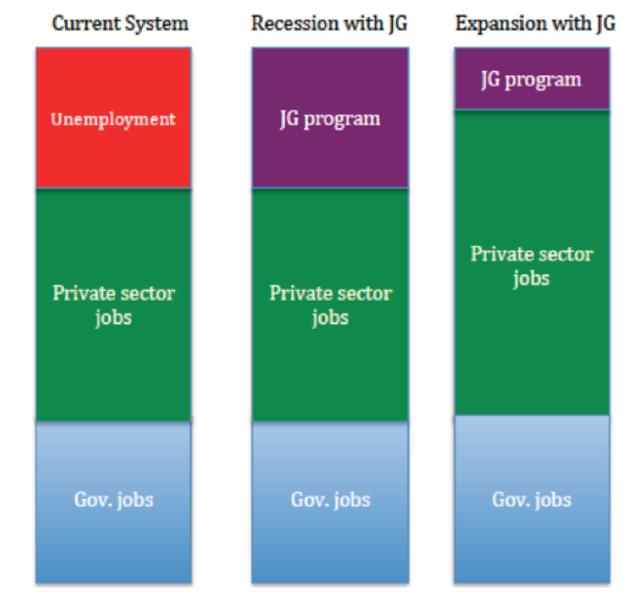

It can implement a national job guarantee program to foster job creation for those willing to work (see Minsky 1965, Tcherneva and Wray 2007, Wray 2007, Mitchell and Wray 2005 for a detailed exposition of Minsky’s proposal for the employer of last resort program). In this program no worker would get paid less than the minimum wage and those able and willing to work would be employed thus reducing the social costs of unemployment and poverty. Contrary to the conventional belief that a job guarantee program would be inflationary, it can be designed to ensure that the deficit spending is at the right level to ensure and maintain full employment by setting a wage anchor and acts like a buffer stock of the unemployed (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Employment fluctuations during the business cycle (current system vs JG)

Source: Kaboub et al, 2015, p.23

The program can be designed not only to provide on the job training but also to increase labor force qualification and the productivity of unemployed workers, which works as an increase in the labor supply. Among its benefits, it reaches social targets by mobilizing resources for additional social services to be provided by the community with gender, racial, and regional effects.

This government initiative can be targeted directly to those unemployed workers “at the bottom” of the income distribution leading to improvement of dignity of those that have been denied the opportunity for social inclusion (Tcherneva 2014). Moreover, the percentage of the population living in poverty or extreme poverty would be significantly reduced.

Rather than an obsessive concern over budget deficits, the current debate should be over whether Ms. Rousseff’s administration could have gotten more. However, the Ms. Rousseff’s administration put itself in a position in which the stimulus measures were too small, short-lived, and poorly designed to deal with the challenges posed by the biggest financial meltdown after the Great Depression and this policy initiative is now seen as a failure. As long as policymakers believe that the federal government faces a budget constraint due to the inappropriate application of the household budget constraint to a sovereign government, there will be resistance to adopt an alternative policy. As argued before, they miss the important point that Brazil cannot be forced by markets to default on its domestic debt. It has attained monetary sovereignty, that is, it issues its own non convertible currency. So far Brazil has shifted the policy narrative towards austerity. It remains to be seen whether alternative policies that promote full employment and price stability will be implemented.