By J.D. Alt

Recent news reports lament the on-going collapse of America’s coal industry―specifically the spectacular loss of jobs which is devastating not only families but entire local economies and communities. On a PBS news report, a woman who’d worked for a local mining company for thirty years teared up and asked the reporter, “What in the world am I going to do?” At a recent event sponsored by Wyoming Public Radio, attendees were asked to fill out 5X7 cards with suggestions about how to answer that question—how to replace the lost coal industry jobs. Under the banner “How to Diversify Wyoming,” the cards were pinned on a bulletin board for everyone to see and discuss. The suggestions ranged from eco-tourism to pot-growing to space-flight support―all good, healthy, creative ideas, (with the possible exception, I think, of space-flight). What suddenly jumped out at me, however―like a jack-in-the-box on a spring―is that implicit in every suggestion written on those 5X7 cards lies a huge, overpowering, built-in assumption about the way the world has to work:

Whatever replaces the lost coal-industry employment has to be profitable.

Of course that’s true, right? In the market-driven, capital-for-profit world heralded by Adam Smith and ingrained in the rational construction of American ethics and reality, this is the only way things can, or should, get done, the only way things are made, or should be made, to happen. This “reality” is so invisibly woven into our mental constructs it might be worth trying to make it visible with some simple “architect’s” diagrams. Doing so, I’m thinking, might shed some light on at least one 5X7 card no one even considered pinning on that bulletin board. And who knows: maybe there are, I’m hoping, other strategies to weave an acceptable American reality.

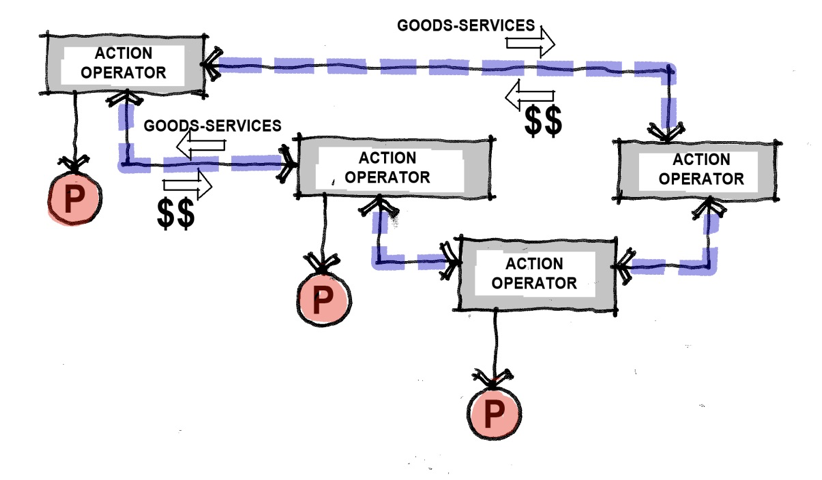

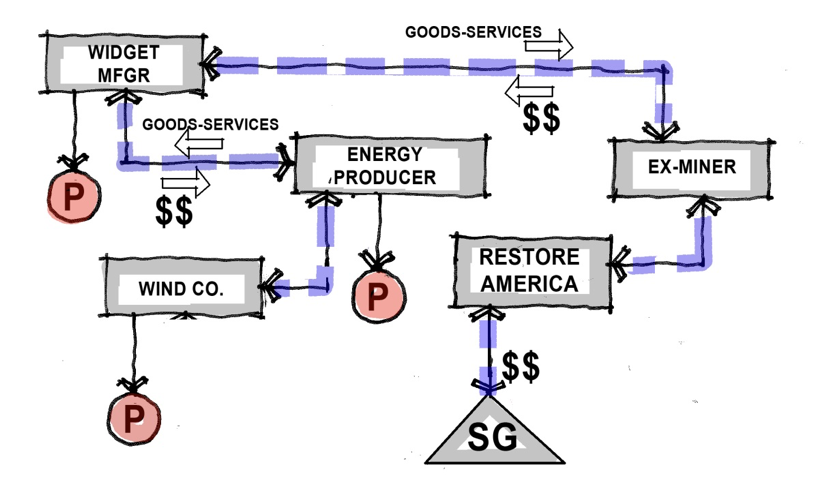

Here’s the diagram that comes to mind:

Depicted are a series of “Action Operators” (people or organizations making something happen) linked together in a kind of chain. In each case, the “link” is a two-way arrow, with dollars flowing in one direction, and the product of action-operations (goods or services) flowing in the other.

Each “Action Operator” (AO) is motivated to produce the goods or services and send them off along the link by the fact that the dollars coming in from the other direction are greater than the dollars they spent in producing the goods and services. This “dollar-profit” is illustrated as being extracted from the AO as the “motivator”―what the AO gets for its efforts. To make the diagram more concrete, let’s make the AOs more specific:

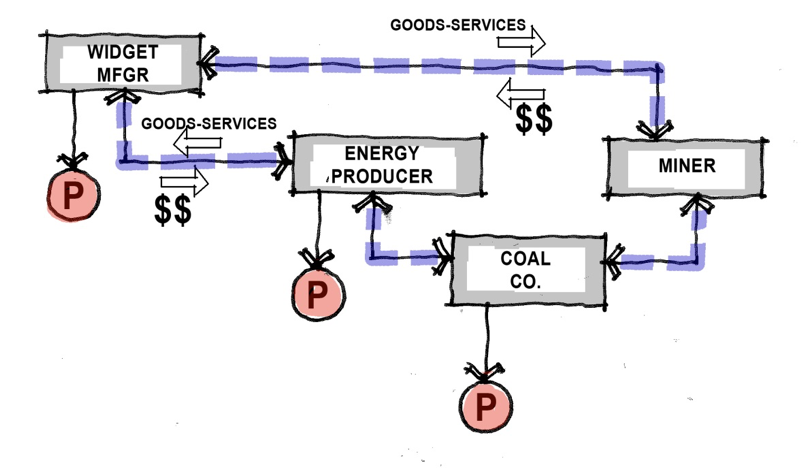

On the left, we have a Widget Mfgr which sends dollars along a link to an Energy Producer. The Energy Producer, in exchange for those dollars received, sends electricity it has produced along the link to the Widget Mfgr who uses the electricity to manufacture the Widgets. The Energy Producer is motivated to do this because it receives more dollars from the Widget Mfgr than it costs the Energy Producer to generate the electricity it sends, creating its motivating “dollar-profit.”

Next in line, we have a Coal Co. which sends coal along its link to the Energy Producer. The Coal Co. is motivated to do this because the dollars it receives in exchange from the Energy Producer are greater than the dollars it spends to produce the coal, generating its own motivating “dollar-profit.”

Next in our economic chain comes the Miner who sends his labor along a link to the Coal Co. The Miner is motivated to provide his labor because the dollars he receives in exchange from the Coal Co. are greater than the dollars it costs to provide his labor. This difference provides the Miner with a net income (his motivating “dollar-profit”) some portion of which is then available for purchasing his necessary, or desired, widgets.

The chained loop is completed with a link between the Miner and the Widget Mfgr. Along this link, the Widget Mfgr sends its widgets to the Miner, and is motivated to do this, like everyone else, because the dollars it receives in exchange from the Miner are greater than the dollars it spends to produce the widgets― this difference, of course, being the Widget Mfgr’s motivating “dollar-profit.”

This chain of actions and motivations is a marvelous system. It makes things happen. It allocates resources and gets things done. It creates lots of jobs for people to do, and it provides them with the net income (dollars) they need to engage in the consumer spending which (as is made evident in the last link of the loop) is the connection that makes the system flow—like when you complete an electrical circuit by pushing a plug into an outlet. This is a dynamic, prolific, and happy diagram―until a thing being done or made to happen no longer generates a profit for one of the Action Operators.

When this happens, links are broken. Without its motivating “dollar-profit,” the AO logically stops producing its goods and services―and, in turn, it stops buying the things (like labor) it was using to produce the goods and services it was making.

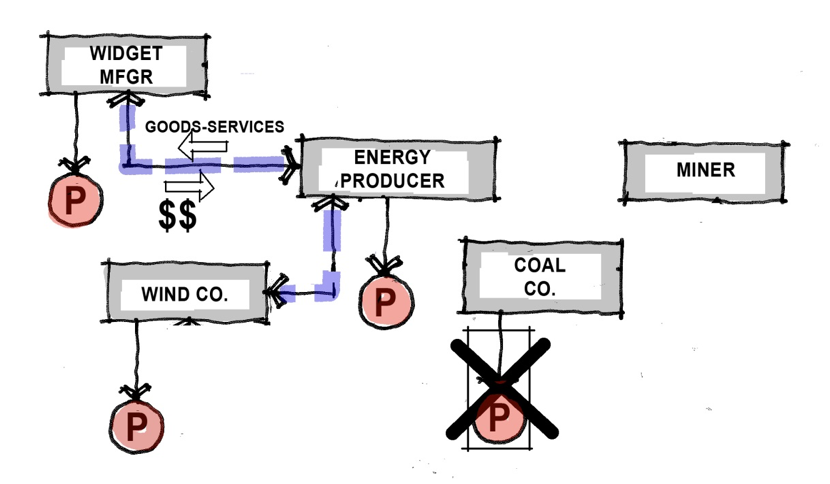

We can now more easily visualize the plight of the coal industry employee in our diagram: The Coal Co. is no longer making a profit by producing its coal and selling it to the Energy Producer. So, logically, it stops producing coal. Two links are immediately severed: the link to the Energy Producer, and the link to the Miner. We’ll assume the link to the Energy Producer is replaced with a new link to, say, a profit-generating wind farm. This means the link between the Energy Producer and the Widget Mfgr remains intact. Whew! Great!

But the link to the Miner remains severed. And, as we can see, the larger loop, itself, is broken: Even though the Widget Mfgr can still buy energy to produce widgets, the Miner no longer has the net income to buy the widgets produced. The flow around the loop comes to a halt. The immediate pain is felt by the Miner, then the Widget Mfgr, but eventually all the AOs and links in the loop are affected.

What to do? According to the Saints of our economic orthodoxy, to repair the loop there is no other way than for the Miner to find a new link to a new Action Operator―a replacement AO driven, of course, by the prospect it will generate a motivating “dollar-profit.” Hence, we have the exercise of the 5X7 cards on the bulletin board―desperate fantasy searches for new, profit-making AOs who might come into the local community, start producing goods and services, and hire the former coal industry workers. Hence, also, we have politicians promising to attract new businesses with friendly “un-regulations,” big tax breaks, free land, mineral and water-rights, and so on―(anything that will help the ventures turn a motivating profit). The politicians get elected, the freebies are extracted, but the ventures, for the most part, fail to create the promised jobs. Profit-seeking capital, efficient and wondrous as it is in making things happen under the right circumstances, is a strange and fickle thing.

This all may seem obvious, but now let’s insert a hypothetical unorthodoxy into our diagram and see what happens. First, let’s take stock of the situation on the ground:

We have a Coal Co.—in business for generations—which now, because it is no longer generating profits, has stopped production. We have a community of people (the now unemployed Miners) who have nothing to do when they get up in the morning―except worry and scramble about how they’re going to find some net income to pay for their essential, life-supporting widgets. We have a local economy, which previously had been providing goods and services to the Miners, which has now lost its customers. And, finally, we have what is inevitably overlooked by our highly sensitive, profit-oriented awareness: a local, natural environment and ecosystem which has been despoiled, degraded, and polluted by decades of mining operations―in many cases, literally a vast series of wastelands, mountains flattened, forests obliterated, valleys and streams filled in with leaching, toxic debris.

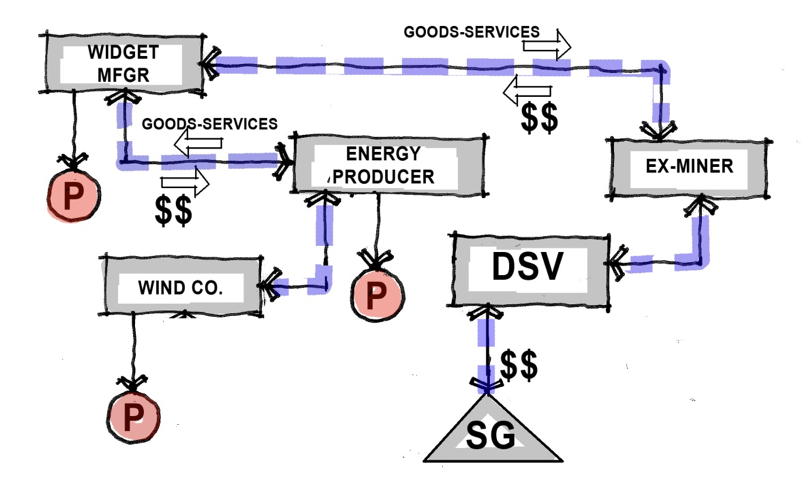

So here’s the hypothetical unorthodoxy I’d like to insert into the diagram―just to see, diagrammatically at least, what happens: The Coal Co. is gone. Rather than wait, cajole, and even resort to various forms of bribery, in the slim hope of attracting some new profit-making business to replace the Coal Co., let’s try a different tactic. Let’s replace the Coal Co. in our diagram with a new “kind” of AO―an Action Operator which doesn’t have to make a profit in order to obtain the capital and cash-flow it needs to undertake the goals it decides to achieve. Let’s call this new kind of Action Operator a “Direct Sovereign Spending Venture” (DSV).

As illustrated, the DSV replaces the “horizontal” link from the Energy Producer with a “vertical” link from the sovereign government (SG). Along this vertical link flow new U.S. fiat dollars issued―at will and as needed―by the U.S. sovereign government. (For a simplified explanation of how and why this can happen, and why it is NOT “spending taxpayer’s dollars) see this video.)

On the other side, the DSV replaces the broken link with the ex-Miners (who are now selling their labor to the DSV). This, in turn, repairs the crucial link between the ex-Miners and the Widget Mfgr. The profit-oriented chain is now flowing again―even though one of its “horizontal” links has been replaced with an unorthodox “vertical” one.

Now we get to the really important part: As the newly issued fiat dollars flow along the link from the sovereign government to the DSV (and hence to the ex-Miners) what are the goods and services that flow, in exchange, in the other direction―and who do they flow to? There are lots of possibilities, but in this particular example the most immediately rational one, from my perspective, is this: The DSV provides the necessary equipment and pays its new employees (the ex-Miners) to repair, de-toxify, and fully restore or reclaim the natural landscapes, waterways, and ecosystems despoiled by the decades of mining operations. This makes a lot of common sense for two reasons: First, the people being employed to do the work―the ex-Miners―are intimately familiar with the problems that need to be addressed, the local “lay of the land,” and the kind of equipment necessary to undertake the work. Second, they have an extra “motivation to excellence” because they are restoring and reclaiming the natural heritage of their own communities: they are restoring and improving their own property values and quality of life. We might call this particular example of a DSV the “Restore America Co.”

Looking at our revised diagram there are now a couple of interesting things to observe and think about. First, will the direct sovereign spending of new fiat dollars to fund operations of the Restore America Co. generate inflation? The diagram suggests the answer is “no,” since the new dollars are simply replacing, in the diagram at least, dollars which previously flowed from a different link (the old link between the Energy Producer and the Coal Co.).

Second, the diagram seems to suggest, very clearly, that it is possible (and quite rational) to replace an underperforming, damaged, or failed link in the market-oriented, capital-for-profit economic chain with a “vertical” direct sovereign spending link. Diagrammatically, it appears that doing so not only doesn’t damage the larger, profit-oriented flow, but reinforces and repairs it. It also seems visibly clear that it is logically possible to insert direct sovereign spending links and ventures without “socializing” major portions of the entire economy. DSVs, in other words, can easily be compatible with―and helpful to―a national market-based, capital-for-profit economic system.

History buffs might point out that what we have done here is simply create a diagram of FDR’s New Deal. But I think we’ve gone a bit further. In the 1930’s the U.S. was not operating with a near 50 year history of pure sovereign fiat money as it is today. FDR’s measures were seen as emergency operations to be replaced, once things started “working” again, with “business a usual.” (That opportunity, of course, didn’t come until after WWII.)

The diagram we’ve just created suggests, I think, the possibility of a new “business as usual” that can, in fact, restore a faltering American Dream. Imagine America’s over-arching, diverse and complex capital-for-profit economic chain being strategically augmented with vertical links to direct sovereign spending ventures. These not-for-profit DSVs will act to repair, strengthen, and make the larger, profit-driven chain more sustainable.

What our diagram has made visible is the fact that with an exclusively “horizontal” capital-for-profit economic chain, the things that are undertaken, or made to happen, can only be those things for which the capital-for-profit business model works. This is not always―or maybe even mostly always―best for the capital-for-profit business model itself. If something doesn’t fit within that model―even if it’s something essential for the collective good―the profit-seeking economic chain will NOT make it happen.

Inserting direct sovereign spending ventures and links into the chain, then, enables collective society to undertake and accomplish a greater diversity of goals―and to achieve things which not only otherwise wouldn’t happen, but which could provide enormous and critical benefits to local communities, economies, and collective society as a whole. What would those strategic, vertically linked DSVs undertake to accomplish? Our diagram’s “Restore America Co. is a perfect example.

15 responses to “A Perfect Example”