The statutory objectives for monetary policy known as the “dual mandate” were imposed by Congress as part of the the Federal Reserve by Act of 1913. The mandate charges the Federal Reserve with responsibility for achieving two broad macroeconomic goals: “maximum employment and stable prices.” Much has been made (especially by those on the left) of the benefits of having a dual mandate. In contrast to the European Central Bank, which operates with a single mandate — price stability — the dual mandate is supposed to ensure a more balanced outcome in the public’s interest.

As Matt Yglesias put it:

The idea of a “dual mandate” to pursue both price stability and maximum employment is that even if a pure look at inflation would lead the Fed to want tighter money, it ought to check out the employment situation and think twice before tightening if joblessness is widespread.

But not everyone is so enamored with the idea of requiring the Fed to care as much about fighting unemployment as it does about restraining inflation. For example, not a single Republican expressed support for the dual mandate when the issue came up during a presidential debate on September 12, 2011.

At the Republican presidential debate on Sept. 12, the major candidates argued that the Fed should instead focus squarely on the goal of long-run price stability.

Responding to a question about the Fed, Rick Santorum said: “make it a single charter instead of a dual charter” institution, and no candidate disagreed. Most piled on. “Its focus needs to be narrowed,” said Herman Cain. “We need to have a Fed that is working towards sound monetary policy,” said Rick Perry. “The Federal Reserve has a responsibility to preserve the value of our currency,” said Mitt Romney.

Former Fed Chairman Paul Volker recently made a similar (but far more nuanced) argument with respect to the dual mandate.

I know that it is fashionable to talk about a “dual mandate”—the claim that the Fed’s policy should be directed toward the two objectives of price stability and full employment. Fashionable or not, I find that mandate both operationally confusing and ultimately illusory. It is operationally confusing in breeding incessant debate in the Fed and the markets about which way policy should lean month-to-month or quarter-to-quarter with minute inspection of every passing statistic. It is illusory in the sense that it implies a trade-off between economic growth and price stability, a concept that I thought had long ago been refuted not just by Nobel Prize winners but by experience.

The Federal Reserve, after all, has only one basic instrument so far as economic management is concerned—managing the supply of money and liquidity. Asked to do too much—for example, to accommodate misguided fiscal policies, to deal with structural imbalances, or to square continuously the hypothetical circles of stability, growth, and full employment—it will inevitably fall short. If in the process of trying it loses sight of its basic responsibility for price stability, a matter that is within its range of influence, then those other goals will be beyond reach.

Volker argues that the Fed would actually do a better job of maintaining high employment if it was freed of its dual mandate and simply assigned broad responsibility for maintaining price stability over time. Perhaps this position is not surprising, given that there was not a single mention of “maximum employment” in any of the Fed’s written directives while Volker was Chairman of the Federal Reserve (see here). But his real beef stems from concerns about the “extraordinary” measures — Quantitative Easing (QE) in particular — the Fed has adopted in an effort to carry out the employment side of its mandate.

Volker is basically worried that the Fed is under too much pressure to bring down unemployment and that recent policy has introduced substantial risks in terms of inflation, financial instability and future credibility. On the unprecedented buying of Treasuries and mortgage backed securities, Volker says:

[T]he extraordinary commitment of Federal Reserve resources, alongside other instruments of government intervention, is now dominating the largest sector of our capital markets, that for residential mortgages. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to note that the Federal Reserve, with assets of $3.5 trillion and growing, is, in effect, acting as the world’s largest financial intermediator.

He’s also worried about the use of “forward guidance” (i.e. the Fed’s promise to keep interest rates low for as long as unemployment remains above 6.5%, even if inflation creeps above its historical 2 percent target).

The implicit assumption behind that siren call must be that the inflation rate can be manipulated to reach economic objectives—up today, maybe a little more tomorrow, and then pulled back on command. But all experience amply demonstrates that inflation, when deliberately started, is hard to control and reverse. Credibility is lost.

It’s important to note that Volker isn’t suggesting that the dual mandate should be lifted so that the Fed can pursue a different set of policy goals. Quite the contrary! What he’s saying is that it would be easier for the Fed to deliver what everyone wants — higher employment and price stability — if we weren’t monitoring them so closely. Apparently, monetary policy is sort of like using a urinal — it’s just harder to do it with someone watching.

Anyway, my point is this. Nearly everyone seems to believe one or both of the following: (1) high levels of employment and low rates of inflation are worthwhile goals; and (2) the Fed is the right agency to deliver on these goals. I don’t dispute the former, but I often wonder about the latter. Heck, even the current Fed Chairman sometimes sounds unconvinced. Here’s an exasperated Ben Bernanke confessing that, despite the extraordinary steps the Fed has taken to expedite the recovery, monetary policy is “not even the ideal tool.”

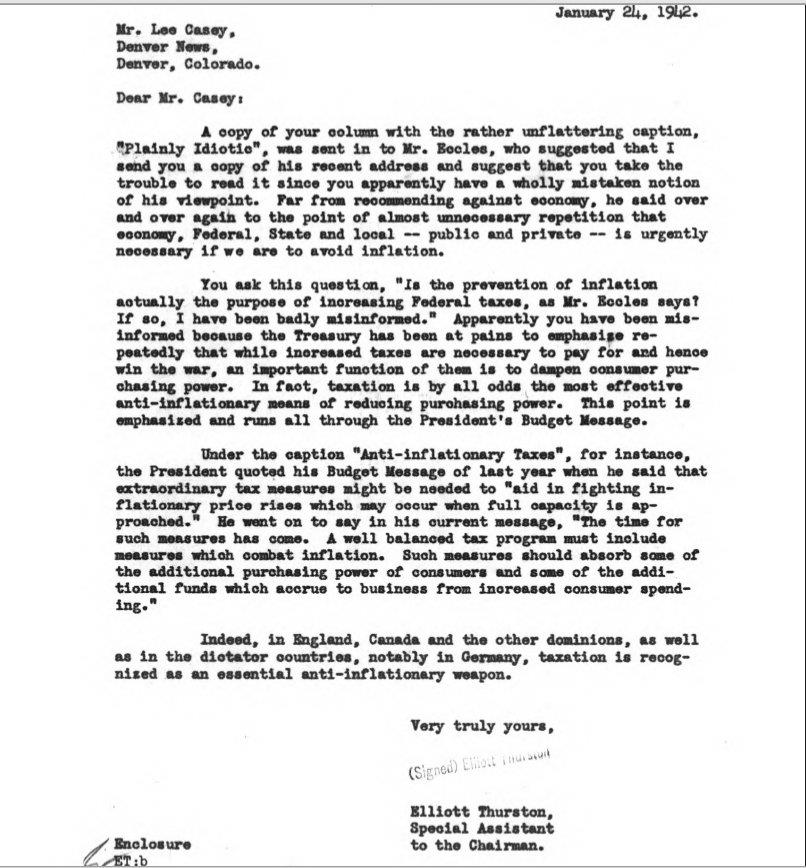

Whereas Bernanke has only hinted at the need for a fiscal partner, former Fed Chairman Marriner Eccles, openly advocated the use of fiscal policy as the most effective way to fight both unemployment and excessive inflation. In the depths of the Great Depression, Eccles pushed for a payroll tax cut, calling it “the most important single step that can be taken” to stimulate consumer buying power. Years later, just prior to the near tripling of U.S. war expenditures, Eccles urged lawmakers to raise the payroll tax in order to stave off an inflationary episode. Indeed, as his Special Assistant made clear in the following letter, Eccles considered adjustments in fiscal policy (in this case an increase in the payroll) to be “the most effective anti-inflationary means of reducing purchasing power.”

Discussions like these continued after the war. Indeed, as Paul Samuelson notes in his classic text Economics (10th Ed), a serious debate took place after the national Commission on Money and Credit advocated greater reliance on fiscal policy to achieve the macro goals of full employment and price stability. The problem, as Samuelson explained, was that the Commission recommended that the President be given unilateral authority to adjust tax rates in response to changing macro conditions. He explained the opposition thusly:

Philosophically, some reformers dislike the need to have human beings decide policy. They speak of a ‘government of laws and not of men.’ They advocate setting up automatic rules and mechanisms that would go into action without ever depending on human decisions. . . we have not yet arrived at a stage where any nation is likely to create for itself a set of constitutional procedures that displace need for discretionary policy formation and responsible human intelligence.

This is basically what the Taylor Rule was supposed to do — i.e. remove political pressures/human agency from monetary policy by automating decisions about whether and by how much to adjust the federal funds rate. With waning evidence that the Fed has sufficient firepower to carry out its dual mandate, perhaps it’s time to develop a fiscal analogue to the Taylor Rule.

Follow Stephanie on Twitter @deficitowl

Pingback: Links 8/7/13 « naked capitalism

Pingback: Some Thoughts on the Dual Mandate: Right Goals,...

Pingback: Berririk ote? | Heterodoxia, diru teoria modernoa eta finantza ingeniaritza