Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

November 2025 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-

Yearly Archives: 2012

Response to Comments on Blog #33: MMT and Inequality

OK there really were only two themes inthe comments: first a question about sovereign vs nonsovereignissuers of IOUs and second questions about the MMT position oninequality.

The first has been dealt with all alongin the MM Primer. The sovereign chooses the unit of account, taxes inthat unit and issues IOUs in that unit that can be used to payobligations to the sovereign. Q. E. D.

On the second: MMTers reject the notionthat sovereign government uses taxes to “redistribute” income.No, taxes destroy income. If we want poor people to have income, wegive them jobs and keystroke their bank accounts. If we think richpeople are too rich we can reverse keystroke their bank accounts.

Here’s the problem. I suppose all ofyou looked at Mitt Romney’s (who on earth would name their kidafter a leather implement used in a baseball game?) tax return.Q.E.D. Forget taxes. Ain’t going to reduce wealth of the rich. Intruth, Romney pays way too much in taxes for someone in his incomeclass—remember, he knew he would run for president and so avoidedall questionable evasions. In spite of what the news is nowreporting, most really rich people do not pay taxes. Don’t take myword for it. Bartlett and Steele (two reporters in Philly) got famousfor going through the thousands of pages of the tax code andidentifying thousands of exemptions for well-connected rich folksthat exempted them from paying taxes. They actually figured outexactly who these people were. There were thousands more they couldnot identify—but the exemptions were so specific that it wasobvious they were meant for some favored individual.

Anyway, suppose someone’s income is$20 million a year like Mitt’s (a piker by Bill Gates standards),what tax rate would we need to levy to significantly reduceinequality? Not 30%. Not 70%. 90%? Ain’t never going to happen. Youwill not pass a tax law imposing a rate of 90% much less actuallymake it stick.

So here is what I wrote:

MMTers have written lots on poverty,inequality and the recent massive concentration of wealth income atthe top, so I have no idea where you get the idea that we avoid thesetopics. Indeed, Kelton and I did a detailed study contrasting the Waron Poverty (which did not reduce poverty at all) with the JG/ELRproposal which would have wiped out two-thirds of all poverty even ifthe wage was set at the minimum wage. I have no idea why you belive JG/ELR would lead to massive underemployment–it leads to fullemployment. So far as I can tell, the complaint is that we have notput them in the Primer? That does not mean we have ignored theissued. For those who want to read our study, go here:

“Public Policy Brief No. 78 | June2004

The War on Poverty after 40 Years: AMinskyan Assessment

Twenty to 25 years ago, a debate wasunder way in academe and in the popular press over the War onPoverty. One group of scholars argued that the war, initiated byPresidents Kennedy and Johnson, had been lost, owing to the inherentineffectiveness of government welfare programs. Charles Murray andother scholars argued that welfare programs only encouragedshiftlessness and burdened federal and state budgets.In recent years,despite the fact that the extent of poverty has not significantlydiminished since the early 1970s, the debate over poverty hasseemingly ended. In a country in which middle-class citizens struggleto afford health insurance and other necessities, the problems of theworst-off Americans seem to many remote and less than pressing.Moreover, the welfare reform bill of 1996 has deflected much of thecriticism of the welfare state by ending the individual-levelentitlement to Aid to Families with Dependent Children benefits (nowknown as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) and putting timelimits on welfare recipiency, among other measures.” Download:Public Policy Brief No. 78, 2004 at www.levy.org.And while you are there browsing the Levy pices you will see I wrotemany other pieces on related topics.

So: to reduce inequality, first youstart at the bottom: give jobs. That eliminates 2/3 of all poverty.Then you gradually raise wages over time, by increasing the JG/ELRbasic wage.

And yes, you tackle income at the top.And as some comments indicated, most of the increase of inequality inrecent years is due to the outrageous rewards in the FIRE sector(finance, insurance, real estate). So you must reduce the rewards inthat sector. There is nothing “natural” about such high rewards.They are due largely to government policy. That is not the topichere, but it begins with the fraudsters and then changescompensations, incentives, and rewards. This is not difficultstuff—American management’s rewards are totally out of linecompared with compensation around the globe. And financialinstitutions—where the biggest rewards are—are inherentlypublic-private partnerships.

On progressive taxes, yes I propose acubic-foot-of-dwelling space tax. It is also environmentally sound.

However, we need to understandpolitical economy as well as MMT. First we do not need to”redistribute” from rich to poor. We can give the poor anyincome we want (hint: “keystrokes”) and any income we takefrom the rich goes no where (hint: reverse those keystrokes). So thatis a bogeyman. We can take BMWs away from the rich and give them tothe poor, if you like. But don’t confuse that with taxes—which areimposed in monetary form. Taking BMWs away is confiscation.

Finally, Americans oppose high taxeson the rich. We may not agree with them but it is the truth. In theUS taxes have never “redistributed” income–the rich justavoid and evade taxes and if that doesn’t work they hire Congress togive them loopholes. Forget it, it will not work in America.

Comments Off on Response to Comments on Blog #33: MMT and Inequality

Posted in MMP, Uncategorized

Tagged MMP

The World Needs 600 Million New Jobs

The International Labor Office (ILO) has just released a sobering report on the growing crisis in world labor markets. We began the year with 1.1billion people – one out of every three people in the global labor force – either unemployed or among the 900 million working poor who earn less than US$2 a day. On top of the existing glut of 200 million unemployed, global labor markets will see an average of 40 million new entrants each year. That means that an additional 400 million jobs will need to be created over the next decade in order to prevent a further increase in unemployment. To employ everyone who wants to work, the world needs 600 million new jobs.

The concern, however, is that global growth is decelerating,which means it will be difficult for global labor markets to keep up with the growth of the labor force, much less make up any lost ground. In 2011, global growth slowed from 5.1 percent to just 4 percent, and the IMF is warning of a further deceleration in 2012. The ILO report warns that even a modest slowdown in 2012, say 0.2 percent points, would mean an additional 1.7 million unemployed by 2013. The report also highlights the impact that overly tight fiscal policies have had on growth and employment, beginning with the job-killing austerity programs that have become especially common within the Eurozone. Elsewhere, in nations with ample policy space, governments have lost their appetite for fiscal stimulus, even as heightened insecurity and depressed consumer confidence keep private sector demand weak.

Analytically, the report begins on a high note, with an analysisthat employs the sectoral balance approach that is central to the MMT framework. Here, the report draws out the (negative) implications of declining public budgets on private net savings. Unfortunately, the authors of the report fail to grasp enough MMT to develop a cogent analysis throughout, particularly whenit comes to distinguishing between currency issuers and currency users. As aresult, the report concludes with a weak-kneed policy prescription to address “the urgent challenge of creating 600 million productive jobs over the next decade.”

Below are some excerpts (my emphasis) to give you a sense of the study’s main conclusions:

Even though only a few countries are facing serious and long-term economic and fiscal challenges, the global economy has weakened rapidly as uncertainty spread beyond advanced economies. As a result, the world economy has moved even further away from the pre-crisis trend path and, at the current juncture, evena double dip remains a distinct possibility.

There is growing evidence of a negative feedback loop between the labour market and the macro-economy, particularly in developed economies: high unemployment and low wage growth are reducing demand for goods and services, which further damages business confidence and leaves firms hesitant to invest and hire. Breaking this negative loop will be essential if a sustainable recovery is to take root. In much of the developing world, such sustainable increases in productivity will require accelerated structural transformation – shifting to higher value added activities while moving away from subsistence agriculture as a main source of employment and reducing reliance on volatile commodity markets for export earnings.

Further gains in education and skills development, adequate social protection schemes that ensure a basic standard of living for the most vulnerable, and strengthened dialogue between workers, employers and governments are needed to ensure broad-based development built on a fair and just distribution of economic gains.

Housing and other asset price bubbles prior to the crisis created substantial sectoral misalignments that need to be fixed and which will requirelengthy and costly job shifts, both across the economy and across countries.

To address the protracted labour market recession and put the world economy on a more sustainable recovery path, several policy changes are necessary.

First, global policies need to be coordinated more firmly. Deficit-financed public spending and monetary easing simultaneously implemented by many advanced and emerging economies at the beginning of the crisis is no longer a feasible option for all of them. Indeed, the large increase in public debt and ensuing concerns about the sustainability of public finances in some countries have forced those most exposed to rising sovereign debt risk premiums to implement strict belt-tightening. However, cross-country spillover effects from fiscalspending and liquidity creation can be substantial and – if used in a coordinated way – could allow countries that still have room for maneuver to support both their own economies as well as the global economy. It is such coordinated public finance measures that are now necessary to support global aggregate demand and stimulate job creation going forward.

Second, more substantial repair and regulation of the financial system would restore credibility and confidence…

Third, what is most needed now is to target the real economy to support job growth. The ILO’s particular concern is that despite large stimulus packages, these measures have not managed to roll back the 27 million increase in unemployed since the initial impact ofthe crisis. Clearly, the policy measures have not been well targeted and need reassessment in terms of their effectiveness. … policies that have proven very effective in stimulating job creation and supporting incomes include: the extension of unemployment benefits and work sharing programmes, there-evaluation of minimum wages and wage subsidies as well as enhancing public employment services, public works programmes and entrepreneurship incentives – show impacts on employment and incomes.

Fourth, additional public support measures alone will not be sufficient to foster a sustainable jobs recovery. Policy-makers must act decisively and in a coordinated fashion to reduce the fear and uncertainty that is hindering private investment so that the private sector can restart the main engine of global job creation. Incentives to businesses to invest in plant and equipment and to expand their payrolls will be essential to stimulate a strong and sustainable recovery in employment.

Fifth, to be effective, additional stimulus packages must not put the sustainability of public finances at risk by further raising public debt. In this respect, public spending fully matched by revenue increases can still provide a stimulus to the real economy, thanks to the balanced budget multiplier. In times of faltering demand, expanding the role of government in aggregate demand helps stabilize the economy and sets forth a new stimulus, even if the spending increase is fully matched by simultaneous rises in tax revenues. As argued in this report, balanced-budget multipliers can be large, especially in the current environment of massively underutilized capacities and high unemployment rates. At the same time, balancing spending with higher revenues ensures that budgetary risk is kept low enough to satisfy capital markets.

The report concludes with the following sentence:

At the same time, balancing spending with higher revenues ensures that budgetary risk is kept low to satisfy capital markets. Interest rates will therefore remain unaffected by such a policy choice, allowing the stimulus to develop its full effect on the economy.

And this is my biggest problem with the report: there is no attempt to distinguish countries that must satisfy capital markets from those that need not. As MMT makes clear, governments that issue “modern money” (i.e. non-convertible fiat currencies) can help restore growth by permitting their deficits to expand to the point where the private sector is satisfied with its net saving position. Only governments that that operate with fixed exchange rates or other incarnations of a gold standard must cow-tow to capital markets. A far bolder jobs program could be advanced if people understood the importance of monetary sovereignty.

Posted in Stephanie Kelton

Tagged 600 million jobs, international labor office report, MMT, Modern Monetary Theory

The New York Times’ Ode to Foxconn and Anti-Employee Control Fraud

I wrote recently about Apple’s release ofinformation from its “audits” of its major suppliers. Apple constructed the release to deny thepublic information on the identity of the suppliers that defrauded andendangered the lives and health of their workers. I explained that criminologists classifythese as “anti-employee control frauds.” Control frauds occur when the persons who control a seemingly legitimateentity use it as a “weapon” to defraud. Anti-employee control frauds defraud the workers. Apple’s audit, and I explained why it was farfrom vigorous, showed endemic anti-employee control fraud by itssuppliers. Apple overwhelminglypurchases components from Asian suppliers that are criminal enterprises. The control frauds operate in fraud-friendlynations with non-Western managers selected for their willingness to cheat theworkers.

Posted in William K. Black

Tagged anti-employee, apple, chinese workers, Control Fraud, exploitation, foxconn

MMP #33: Functional Finance and Long Term Growth

Last weekwe examined Milton Friedman’s version of Functional Finance, which we found tobe remarkably similar to Abba Lerner’s. If the economy is operating below fullemployment, government ought to run a budget deficit; if beyond full employmentit should run a surplus. He also advocated that all government spendingshould be financed by “printing money” and taxes would destroy money. That, aswe know, is an accurate description of sovereign government spending—exceptthat it is keystrokes, not money printing. Deficits mean net money creation, throughnet keystrokes. The only problem with Friedman’s analysis is that he did notaccount for the external sector: he wanted a balanced budget at fullemployment, but if a country tends to run a trade deficit at full employment,then it must have a government budget deficit to allow the private sector torun a balanced budget—which is the minimum we should normally expect.

Somehow allthis understanding was lost over the course of the postwar period, replaced by“sound finance” which is anything but sound. It was based on an inappropriateextension of the household “budget constraint” to government. This is obviouslyinappropriate—households are users of the currency, while government is theissuer. It doesn’t face anything like a household budget constraint. How couldeconomics have become so confused? Let us see what Paul Samuelson said, andthen turn to proper policy to promote long term growth.

Functional Finance versus Superstition. The functional finance approach ofFriedman and Lerner was mostly forgotten by the 1970s. Indeed, it was replacedin academia with something known as the “government budget constraint”. Theidea is simple: a government’s spending is constrained by its tax revenue, itsability to borrow (sell bonds) and “printing money”. In this view, governmentreally spends its tax revenue and borrows money from markets in order tofinance a shortfall of tax revenue. If all else fails, it can run the printingpresses, but most economists abhor this activity because it is believed to behighly inflationary. Indeed, economists continually refer to hyperinflationaryepisodes—such as Germany’s Weimar republic, Hungary’sexperience, or in modern times, Zimbabwe—asa cautionary tale against “financing” spending through printing money.

Note thatthere are two related points that are being made. First, government is“constrained” much like a household. A household has income (wages, interest,profits) and when that is insufficient it can run a deficit through borrowingfrom a bank or other financial institution. While it is recognized thatgovernment can also print money, which is something households cannot do, theseis seen as extraordinary behaviour—sort of a last resort. There is norecognition that all spending bygovernment is actually done by crediting bank accounts—keystrokes that are moreakin to “printing money” than to “spending out of income”. That is to say, thesecond point is that the conventional view does not recognize that as theissuer of the sovereign currency, government cannot really rely on taxpayers or financial markets to supply itwith the “money” it needs. From inception, taxpayers and financial markets canonly supply to the government the “money” they received from government. That is to say, taxpayers pay taxes usinggovernment’s own IOUs; banks use government’s own IOUs to buy bonds fromgovernment.

Thisconfusion by economists then leads to the views propagated by the media and bypolicy-makers: a government that continually spends more than its tax revenueis “living beyond its means”, flirting with “insolvency” because eventuallymarkets will “shut off credit”. To be sure, most macroeconomists do not makethese mistakes—they recognize that a sovereign government cannot really becomeinsolvent in its own currency. They do recognize that government can make allpromises as they come due, because it can “run the printing presses”. Yet, theyshudder at the thought—since that would expose the nation to the dangers ofinflation or hyperinflation. The discussion by policy-makers—at least in the US—is far moreconfused. For example, President Obama frequently asserted throughout 2010 thatthe USgovernment was “running out of money”—like a household that had spent all themoney it had saved in a cookie jar.

So how didwe get to this point? How could we have forgotten what Lerner and Friedmanclearly understood?

In a veryinteresting interview in a documentary produced by Mark Blaug on J.M. Keynes,Samuelson explained:

“I think there is an elementof truth in the view that the superstition that the budget must be balanced atall times [is necessary]. Once it is debunked [that] takes away one of thebulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. Theremust be discipline in the allocation of resources or you will have anarchisticchaos and inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion wasto scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in away that the long-run civilized life requires. We have taken away a belief inthe intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year, [then] inevery short period of time. If Prime Minister Gladstone came back to life he would say “uh, oh what youhave done” and James Buchanan argues in those terms. I have to say that Isee merit in that view.”

The beliefthat the government must balance its budget over some timeframe is likened to a“religion”, a “superstition” that is necessary to scare the population intobehaving in a desired manner. Otherwise, voters might demand that their electedofficials spend too much, causing inflation. Thus, the view that balancedbudgets are desirable has nothing to do with “affordability” and the analogiesbetween a household budget and a government budget are not correct. Rather, itis necessary to constrain government spending with the “myth” precisely becauseit does not really face a budget constraint.

The US (and manyother nations) really did face inflationary pressures from the late 1960s untilthe 1990s (at least periodically). Those who believed the inflation resultedfrom too much government spending helped to fuel the creation of the balancedbudget “religion” to fight the inflation. The problem is that what started assomething recognized by economists and policymakers to be a “myth” came to bebelieved as the truth. An incorrect understanding was developed. Originally themyth was “functional” in the sense that it constrained a government thatotherwise would spend too much, creating inflation. But like many useful myths,this one eventually became a harmful myth—an example of what John KennethGalbraith called an “innocent fraud”, an unwarranted belief that preventsproper behaviour. Sovereign governments began to believe that the really couldnot “afford” to undertake desired policy, on the belief they might becomeinsolvent. Ironically, in the midst of the worst economic crisis since theGreat Depression of the 1930s, President Obama repeatedly claimed that the US governmenthad “run out of money”—that it could not afford to undertake policy that mostbelieved to be desired. As unemployment rose to nearly 10%, the government wasparalysed—it could not adopt the policy that both Lerner and Friedmanadvocated: spend enough to return the economy toward full employment.

Ironically,throughout the crisis, the Fed (as well as some other central banks, includingthe Bank of England and the Bank of Japan) essentially followed Lerner’s secondprinciple: it provided more than enough bank reserves to keep the overnightinterest rate on a target that was nearly zero. It did this by purchasingfinancial assets from banks (a policy known as “quantitative easing”), inrecord volumes ($1.75 trillion in the first phase, with a planned additional $600billion in the second phase). Chairman Bernanke was actually grilled inCongress about where he obtained all the “money” to buy those bonds. He(correctly) stated that the Fed simply created it by crediting bankreserves—through keystrokes. The Fed can never run out “money”; it can affordto buy any financial assets banks are willing to sell. And yet we have thePresident (as well as many members of the economics profession as well as mostpoliticians in Congress) believing government is “running out of money”! Thereare plenty of “keystrokes” to buy financial assets, but no “keystrokes” to paywages.

Thatindicates just how dysfunctional the myth has become.

A Budget Stance to Promote Long Term Growth. The lesson that can be learned fromthat three decade experience of the US is that in the context of a privatesector desire to run a budget surplus (to accumulate savings) plus a propensityto run current account deficits, the government budget must be biased to run adeficit even at full employment. Thisis a situation that had not been foreseen by Friedman (not surprising since theUSwas running a current account surplus in the first two decades after WWII). Theother lesson to be learned is that a budget surplus (like the one PresidentClinton presided over) is not something to be celebrated as anaccomplishment—it falls out of an identity, and is indicative of a privatesector deficit (ignoring the current account). Unlike the sovereign issuer ofthe currency, the private sector is a user of the currency. It really does facea budget constraint. And as we now know, that decade of deficit spending by theUSprivate sector left it with a mountain of debt that it could not service. Thatis part of the explanation for the global financial crisis that began in the US.

To be sure,the causal relations are complex. We should not conclude that the cause of the private deficit was the Clinton budget surplus; and we should not conclude thatthe global crisis should be attributed solely to US household deficit spending. Butwe can conclude that accounting identities do hold: with a current accountbalance of zero, a private domestic deficit equals a government surplus. And ifthe current account balance is in deficit, then the private sector can run asurplus (“save”) only if the budget deficit of the government is larger thanthe current account deficit.

Finally,the conclusion we should reach from our understanding of currency sovereigntyis that a government deficit is more sustainable than a private sector deficit—thegovernment is the issuer, the household or the firm is the user of thecurrency. Unless a nation can run a continuous current account surplus, thegovernment’s budget will need to be biased to run deficits on a sustained basisto promote long term growth.

However, weknow from our previous discussion that fiscal policy space depends on theexchange rate regime—the topic of the next blog.

Further, wewant to be clear: the appropriate budget stance depends on the balance of theother two sectors. A nation that tends to run a current account surplus can runtighter fiscal policy; it might even be able to run a sustained governmentbudget surplus (this is the case in Singapore—which pegs its exchangerate, and runs a budget surplus because it runs a current account surplus whileit accumulates foreign exchange). A government budget surplus is alsoappropriate when the domestic private sector runs a deficit (given a currentaccount balance of zero, this must be true by identity). However, for thereasons discussed above, that is not ultimately sustainable because the privatesector is a user, not an issuer, of the currency.

Finally, we must note that it is not possible for all nations to runcurrent account surpluses—Asian net exporters, for example, rely heavily onsales to the US, which runs a current account deficit to provide the Dollarassets the exporters want to accumulate. We conclude that at least somegovernments will have to run persistent deficits to provide the net financialassets desired by the world’s savers. It makes sense for the government of thenation that provides the international reserve currency to fill that role. Forthe time being, that is the US government.

Response to blog #32: Friedman’s Functional Finance Approach

Thanks for comments and questions. As I had alreadyintervened, I addressed the main points related to this week’s blog already.Let me pick up a few loose ends, and reformat my earlier response.

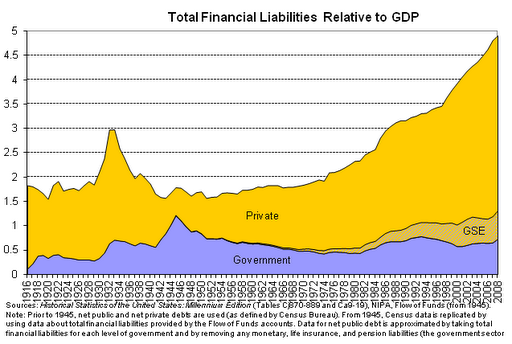

Q1: When you said US Debt/GDP reached 500% was that allprivate debt? And how can the private sector get out of debt?

A: No. Here’s the data break-down. You can see that it iscertainly private debt that has exploded, however. This ends in 2008, and afterthe GFC hit and the US slowed down, government debt started growing rapidly andprivate debt came down a bit as a percent of GDP so it would look a bitdifferent today.

How does the private sector get out of debt? If GDP andincome grow, households can service more debt all else equal, and the ratiowill decline. They can pay off debt. And yes they can default. Note how sharplythe debt ratio came down after the Great Depression—as all 3 of those thingshappened. The most important was economic growth fueled by government spending(and record govt deficits of 25% of GDP during WWII). It can also go down as theeconomy uses export-led growth but for the US that is not likely. The best waywould be to ramp up government spending today.

Q2: Several questions on US current account deficits,foreign accumulation of US Dollar assets, and so on. Also on the Bretton WoodsSystem.

A: I have discussed that a bit previously and we’ll do a lotmore of it in coming weeks—so let’s hold off. With respect to BW: it was amistake. Failed. Worked in the beginning because ROW needed US exports afterWWII and US lent dollars so they could buy them (Marshall Plan). More coming inthe MMP on exchange rate regimes. But briefly, both the BW system and theSterling system (pre WWI) failed. Such international pegged systems do notwork—they always generate crises and then collapse.

Q3: Didn’t Clinton announce he would retire the debt? Did hebelieve it?

A: Yes Clinton appeared on TV and announced all govt debtwould be retired. Who knows or cares what he believed? I think it was Rubin whopushed the idea. But what matters is that all Democrats after him think thatwas the right thing to do, and claim Bush Jr blew it by not continuing with thesurpluses. And so they want to bring back the good old Clinton-Rubin policy assoon as they can get through this crisis! They learned no lessons from thedeath of Goldilocks. Clinton’s tight fiscal policy killed her deader thanElvis.

Q4: Didn’t budget deficits of big-spending Democrats in the1960s cause high inflation?

A: Deficits of the 60s were miniscule. Don’t take my word for it. You can checkit out. Until Obama, no Democratic administration ran big deficits after WWII.Again, check it out. Yes there was some inflation in the late 60s. Big warsusually do generate some—but the war against Viet Nam plus the wimpy and failed“War on Poverty” did not create big deficits because the economy grew fastenough to generate tax revenue. Republicans have always had the biggestdeficits—not necessarily due to big spending, but due to their rotteneconomies that do not grow. Coincidence? Me thinks not.

Q5: Don’t you accept the dollar because you can convert itto gold?

A: Hah: I’ve never done so and would never consider it. Goldis a fool’s gamut. We all accept Dollars because there is a tax system thatrequires them.

Q6: Later Friedman said inflation results from excessivemoney supply.

A: Yes, and he was wrong then and he’s still wrong. Hisfunctional finance paper is probably the only thing he ever got right. Andnobody reads it!

Comments Off on Response to blog #32: Friedman’s Functional Finance Approach

Posted in MMP, Uncategorized

Tagged MMP

Anti-employee Control Fraud

Apple has released a report on working conditions inits suppliers’ factories. It highlightsa form of control fraud that criminology has identified but rarelydiscussed. I write overwhelmingly aboutaccounting control fraud because it drives our recurrent, intensifyingfinancial crises. The primary intendedvictims of accounting control frauds are the shareholders and thecreditors. Other private sector controlfrauds target customers (e.g., George Akerlof’s 1970 article on “lemons”), andthe public (e.g., the unlawful disposal of toxic waste, illegal logging, andtax fraud).

Anti-employee control frauds most commonly fall infour broad, but not mutually exclusive, categories – illegal work conditionsdue to violation of safety rules, violation of child labor laws, failure to payemployees’ wages and benefits, and frauds based on goods and loans provided bythe employer to the employee that lock the employee into quasi-slavery. Apple has just released a report on itssuppliers that shows that anti-employeecontrol fraud is the norm. Remember,fraud is hidden and is often not discovered and Apple did not have an incentiveto make an exhaustive investigation. Apple calls its inquiries “audits” and it is apparent that most of itsinformation comes from reviewing written and electronic records at itssuppliers. That is exceptionallyrevealing. The suppliers know that theycan defraud their employees with such impunity that they don’t even bother toget rid of records that prove their frauds. Apple has resisted making public its suppliers and the report refused toidentify which suppliers committed which violations – often for years despiterepeated, false promises to end their anti-employee control frauds. Two other facts are evident (but notreported). First, Apple rarelyterminates suppliers for defrauding their employees – even when the fraudsendanger the lives and health of the workers and the community – and even whereApple knows that the supplier repeatedly lies to Apple about these fraudulentand lethal practices. Second, it appearsunlikely in the extreme that Apple makes criminal referrals on its supplierseven when they commit anti-employee control frauds as a routine practice, evenwhen the frauds endanger the worker’s and the public’s health, and even whenthe supplier repeatedly lies to Apple about the frauds. Apple’s report, therefore, understatessubstantially the actual incidence of fraud by the 156 suppliers (accountingfor 97% of its payments to suppliers).

“The company said audits revealed that93 supplier facilities had records indicating that more than half of theirworkers exceed a 60-hour weekly working limit. Apple said 108 facilities didnot pay proper overtime as required by law. In 15 facilities, Apple foundforeign contract workers who had paid excessive recruitment fees to laboragencies.

And though Apple said it mandatedchanges at those suppliers, and some facilities showed improvements, inaggregate, many types of lapses remained at levels that have persisted foryears.”

The New YorkTimes, Wall Street Journal, and theWashington Post articles on the Apple report are all lengthy, but none ofthem has any input from a criminologist and each of the articles misses most ofthe significance of the report. I havealready brought out several of these deficiencies. The most fundamental flaws, however, have todo with why anti-employee control fraud is the norm at Apple’s suppliers andwhy the suppliers typically don’t even take the inexpensive efforts necessaryto avoid holding a paper trail that makes the frauds obvious even to a notterribly vigorous audit that they know is coming.

If there is one single thing that drives uswhite-collar criminologists around the bend it is the implicit assumption thatfraud cannot be common. There is, ofcourse, no logical (or experiential) reason for this belief. Nevertheless, it is a common belief and amongeconomists it is a virtually universal dogma. Economists have a tribal taboo against even using the word “fraud” todescribe individual frauds. The surestway to be considered an un-serious economist is to use the “f” word to describefrauds by elite economic actors. Economists’ taboo is particularly bizarre because it is economic theory,developed by a Nobel Laureate that explains why fraud can become endemic. George Akerlof, in his famous article onmarkets for “lemons” (largely describing anti-customer control fraud),explained the perverse “Gresham’s” dynamic in 1970.

“[D]ishonest dealingstend to drive honest dealings out of the market. The cost of dishonesty,therefore, lies not only in the amount by which the purchaser is cheated; thecost also must include the loss incurred from driving legitimate business outof existence.”

Anti-employee control fraud creates real economicprofits for the firm and can massively increase the controlling officers’wealth. Honest firm normally cannotcompete with anti-employee control frauds, so bad ethics drives good ethics outof the markets. Companies like Apple andits counterparts create this criminogenic environment by selecting least-cost –criminal – suppliers who offer components at prices that honest firms cannotmatch. Effectively, they hang out a sign– only the fraudulent need apply to be suppliers. But the sign is, of course, invisible andcannot be introduced in court so Apple and its peers also get deniability. They are shocked, shocked that its suppliersare frauds that cheat their employees and put them and the public’s health atrisk in order to make a few extra yuan ordong for the senior officers.

Fraudulent suppliers, therefore, have compellingincentives to locate in nations and regions in which they can commit fraud withimpunity. The best way to evaluate thefraudulent CEOs’ view as to the risk of prosecution for their frauds is toobserve whether they take cheap means of hiding their frauds. When the CEOs do not even bother to avoidcreating a paper trail documenting their frauds one knows that they view therisk of prosecution as trivial. Nationsthat are corrupt, have weak rule of law, weak or non-existent unions, poorprotections for workers, a reserve army of the impoverished, and have fewresources devoted to prosecuting elite white-collar crime provide an idealcriminogenic environment for firms engaged in anti-employee control fraud. The ubiquitous nature of anti-employeecontrol fraud (and tax fraud) in many nations explains why U.S. industries havebeen so eager to “outsource” U.S. jobs to fraud-friendly nations. Companies like Apple also discovered long agothat Americans often made poor senior managers in these nations because theyobjected to defrauding workers. Not aproblem – there are plenty of managers from other nations that have no suchethical restraints. Foreign suppliersrun by Asian managers are increasingly dominant.

The endemic nature of anti-employee control fraudalso demonstrates an important technical point. The wages reported in the most fraud-friendly nations are substantiallyoverstated because workers work far longer hours without receiving thecompensation to which they are entitled. Their hourly rate is much lower than reported, which means that the wagegap between U.S. and the most fraud-friendly nations is significantly greaterthan reported. U.S. firms that haveforeign suppliers in these nations are well aware of this data bias and maketheir outsourcing decisions based on the real (much larger) wage gap.

TheHarm to Employee and Consumer Health is Grave

The NYT article notes that it was badpublicity in the U.S. that finally forced Apple to make greater disclosuresabout its suppliers’ frauds.

“The calls for Apple to disclosesuppliers became particularly acute after a series of deaths and accidents inrecent years. In the last two years at firms supplying services to Apple, 137employees were seriously injured after cleaning iPad screens with n-hexane, atoxic chemical that can cause nerve damage and paralysis; over a dozen workershave committed suicide or fell or jumped from buildings in a manner thatsuggests a suicide attempt; and in two separate blasts caused by dust frompolishing iPad cases, four were killed and 77 injured.”

The Washington Post article noted:

“Apple found that 62 percent of the 229 facilitiesit inspected were not in compliance with the company’s maximum 60-hour workpolicy; 13 percent did not have adequate protections for juvenile workers; and32 percent had problems with the management of hazardous waste.

One supplier was caught dumping wastewater at anearby farm. Another had a total lack of safety measures, creating “unsafeworking conditions,” the report found. Five facilities employed underageworkers.

The company in the past had refused to divulge itsfull supplier list even as it became standard practice for multinationalcorporations to do so after the public outcry in the 1990s over labor problemsat Nike factories in developing countries.

Apple’s change of heart follows a highly publicizedstring of factory worker suicides in 2010 and deadly explosions in two Chinesefactories in 2011.”

The WSJ emphasized this chillingfinding:

“The report also found 24 facilities conducted pregnancytests and 56 didn’t have procedures to prevent discrimination against pregnantworkers. Apple said that at its direction, the suppliers have stoppeddiscriminatory screenings for medical conditions or pregnancy.”

The article does not make this point explicitly, but these firms conductthese tests in order to unlawfully coerce their pregnant employees to haveundesired abortions in order to obtain and keep their jobs.

ForeignAnti-employee Control Fraud harms U.S. Workers

These frauds take place abroad, but they harm employees in the U.S. Mitt Romney explains that Bain had to slashwages and pensions to save firms located in the U.S. who had to meetcompetition from foreign anti-employee control frauds. The damage from foreign anti-employee controlfrauds drives the domestic attack on U.S. manufacturing wages. Bad ethics increasingly drive good ethics outof the markets and manufacturing jobs out of the U.S. and into morefraud-friendly nations.

A final caution is in order because each of the major articles on the Applereport failed to mention it. CEOs whoare willing to routinely defraud their workers and expose them to grave threatsto their health are exceptionally likely to commit other forms of controlfraud.

Bill Black is the author of The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One and an associate professor of economics and law at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He spent years working on regulatory policy and fraud prevention as Executive Director of the Institute for Fraud Prevention, Litigation Director of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and Deputy Director of the National Commission on Financial Institution Reform, Recovery and Enforcement, among other positions.

Bill writes a column for Benzinga every Monday. His other academic articles, congressional testimony, and musings about the financial crisis can be found at his Social Science Research Network author page and at the blog New Economic Perspectives.

Follow him on Twitter: @WilliamKBlack

MMP BLOG #32: MILTON FRIEDMAN’S VERSION OF FUNCTIONAL FINANCE: A PROPOSAL FOR INTEGRATION OF FISCAL AND MONETARY POLICY

In thecontext of today’s conventional wisdom about the dangers of budget deficits,Lerner’s views (examined last week) appear somewhat radical. What is surprisingis that they were not all that radical at the time. As everyone knows, MiltonFriedman was a conservative economist and a vocal critic of “big government”and of Keynesian economics. No one has more solid credentials on the topic ofconstraining both fiscal and monetary policy than Friedman. Yet, in 1948 hemade a proposal that was almost identical to Lerner’s functional finance views.On one hand, this demonstrates how far today’s debate has moved away from aclear understanding of the policy space available to a sovereign government,but also that Lerner’s ideas must have been “in the air”, so to speak, widelyshared by economists across the political spectrum. At the end of thissubsection we will also visit Paul Samuelson’s comment on this topic—whichprovides a cogent explanation for today’s confusion about fiscal and monetarypolicy. As Samuelson hints, the confusion was purposely created in order tomystify the subject.

Briefly,Milton Friedman’s 1948 article, “AMonetary and Fiscal Framework for Economic Stability” put forward aproposal according to which the government would run a balanced budget only atfull employment, with deficits in recession and surpluses in economic booms.There is little doubt that most economists in the early postwar period sharedFriedman’s views on that. But Friedman went further, almost all the way toLerner’s functional finance approach: all government spending would be paid forby issuing government money (currency and bank reserves); when taxes were paid,this money would be “destroyed” (just as you tear up your own IOU when it isreturned to you). Thus, budget deficits lead to net money creation. Surpluseswould lead to net reduction of money.

He thusproposed to combine monetary policy and fiscal policy, using the budget tocontrol monetary emission in a countercyclical manner. (He also would haveeliminated private money creation by banks through a 100% reserverequirement–an idea he had picked up from Irving Fisher and Herbert Simons inthe early 1930s–hence, there would be no “net” money creation byprivate banks. They would expand the supply of bank money only as theyaccumulated reserves of government-issued money. We will not address this partof the proposal.) This stands in stark contrast to later conventional views(such as those associated with the ISLM model taught in textbooks) that“dichotomized monetary and fiscal policy. Friedman, too, later argued that thecentral bank ought to control the money supply, delinking in his later work theconnection between fiscal policy and monetary policy. But at least in this 1948paper he clearly tied the two in a manner consistent with Lerner’s approach.

Friedmanbelieved his proposal results in strong counter-cyclical forces to helpstabilize the economy as monetary and fiscal policy operate with combinedforce: deficits and net money creation when unemployment exists; surpluses andnet money destruction when at full employment. Further, his plan forcountercyclical stimulus is rules-based, not based on discretionary policy—itwould operate automatically, quickly, and always at just the right level. As iswell known, he later became famous for his distrust of discretionary policy,arguing for “rules” rather than “authorities”. This 1948 paper provides a neatway of tying policy to rules that automatically stabilize output and employmentnear full employment.

We see thatFriedman’s “proposal” is actually quite close to a description of the waythings work in a sovereign nation. When government spends, it does so bycreating “high powered money” (HPM)–that is, by crediting bankreserves. When it taxes, it destroys HPM, debiting bank reserves. A deficitnecessarily leads to a net injection of reserves, that is, to what Friedmancalled money creation. Most have come to believe that government finances itsspending through taxes, and that deficits force the government to borrow backits own money so that it can spend. However, any close analysis of the balancesheet effects of fiscal operations shows that Friedman (and Lerner) had itabout right.

But if thatis so, why do we fail to maintain full employment? The problem is that theautomatic stabilizers are not sufficiently strong to offset fluctuations ofprivate demand. Below we will examine why that is the case.

Note thatFriedman would have had government deficits and, thus, net money emission solong as the economy operated below full employment. Again, that is quite closeto Lerner’s functional finance view, and as discussed above it was a commonview of economists in the early postwar period. But almost no respectableeconomist or politician will today go along with that on the belief it would beinflationary and/or would bust the budget. Such is the sorry state of economicseducation today. How did we get to this point? In last week’s blog, Samuelsonexplained that the belief that the government must balance its budget over sometimeframe a “religion”, a “superstition” that is necessary to scare thepopulation into behaving in a desired manner. Otherwise, voters might demandthat their elected officials spend too much, causing inflation. Thus, the viewthat balanced budgets are desirable has nothing to do with “affordability” andthe analogies between a household budget and a government budget are notcorrect. Rather, it is necessary to constrain government spending with the“myth” precisely because it does not really face a budget constraint.

A Budget Stance for Economic Stability. In Friedman’s proposal, the sizeof government would be determined by what the population wanted government toprovide. Tax rates would then be set in such a way so as to balance the budgetonly at full employment. Obviously that is consistent with Lerner’s approach—ifunemployment exists, government needs to spend more, without worrying aboutwhether that generates a budget deficit. Essentially, Friedman’s proposal is tohave the budget move countercyclically so that it will operate as an automaticstabilizer. And, indeed, that is how modern government budgets do operate:deficits increase in recessions and shrink in expansions. In robust expansions,budgets even move to surpluses (this happened in the US during theadministration of President Clinton). Yet, we usually observe that these swingsto deficits are not sufficiently large to keep the economy at full employment.The recommendations of Friedman and Lerner to operate the budget in a mannerthat maintains full employment are not followed. Why not? Because the automaticstabilizers are not sufficiently strong.

To build in sufficient countercyclical swingsto move the economy back to full employment requires two conditions. First,government spending and tax revenues must be strongly cyclical–spending needsto be countercyclical (increasing in a downturn), and taxes pro-cyclical(falling in a downturn). One way to make spending automatically countercyclicalis to have a generous social safety net so that transfer spending (onunemployment compensation and social assistance) increases sharply in adownturn. Alternatively, or additionally, tax revenues also need to be tied toeconomic performance–progressive income or sales taxes that movecountercyclically.

Second,government needs to be relatively large. Hyman Minsky (1986) used to say thatgovernment needs to be about the same size as overall investment spending–orat least, swings of the government’s budget have got to be as big as investmentswings, moving in the opposite direction. (This is based on the belief thatinvestment is the most volatile component of GDP. This includes residentialreal estate investment, which is an important driver of the business cycle inthe US. The idea is that government spending needs to swing sufficiently and inthe opposite direction to investment in order to keep national income andoutput relatively stable; that, in turn will keep consumption relativelystable.) According to Minsky, government was far too small in the 1930s tostabilize the economy–even during the height of the New Deal, the federalgovernment was only 10% of GDP. Today, all major OECD nations probably have agovernment that is big enough, although some developing countries probably havea government that is too small by this measure. Based on current realities, itlooks like the national government should range from the US low of less than20% of GDP to a high of 50% in France. The countries at the low end of therange need more automatic fluctuation built into the budget than those with abigger government.

Looking tothe decade of the 1960s in the US, one sees that it was more-or-less consistentwith Friedman’s proposal and with Lerner’s functional finance approach. Federalgovernment spending averaged around 18-20% of GDP, and deficits averaged $4 or$5 billion a year, except for 1968 when they temporarily increased to $25billion–but for the decade, deficits ran well under 1% of GDP on average. Wecould quibble about whether the US was at full employment in the 1960s, but itwas certainly closer to full employment during that decade than it was afterthe early 1970s. From the early 1970s until the boom of the 1990s during thepresidency of Bill Clinton, the budget was too tight relative to therecommendations of Friedman and Lerner. How do we know? Because unemploymentwas chronically too high—even in expansions it never got down to 1960s levels.

Note thatthis was not because government spending fell much, or because taxes wereraised. Indeed, the deficit tended to be much higher after the early 1970s (thehigh unemployment period) than it was during the 1960s (the low unemploymentperiod).

What went wrong? Briefly, the problem could be attributed tothe evolution of the international position of the US that led to a chroniccurrent account deficit. The US emerged from WWII in a dominant position—notonly was the dollar in high demand, but so were US exports—needed bywar-ravaged Europe and Japan. The US had a trade surplus, and lent Dollars tothe rest of the world to buy its output. That added to US demand and—from ouraccounting identities—kept our budget deficits small and let our private sectorrun surpluses (save).

Recall thatthe international monetary system (Bretton Woods) was based on a dollar-goldstandard, with exchange rates fixed to the Dollar and the Dollar convertible togold. By the early 1970s, the US was running a trade deficit and foreignholders were exchanging excess dollars for gold. To make a long story short,the US abandoned gold, the Bretton Woods system collapsed, and most developedcountries floated. The dollar fell in value (helping to generate inflationpressures in the US as imports, especially oil, got more expensive), and the USfound it harder to compete in international markets (Japan and Europe hadlargely recovered and were producing for their own markets—and even for the USconsumer). The current account deficit turned negative—more or lesspermanently–during the administration of President Reagan. As we know from ourmacro identities, that deficit would have to be offset by a growing budgetdeficit—which had to be large enough to offset both the current account as wellas the US domestic sector surplus (saving of households and firms). By the endof the 1980s, Congress and the new president (George Bush) agreed to try toreign-in deficit spending. Hence, an already too-small budget deficit (giventhe current account deficit and the desire of the domestic private sector torun surpluses, demand was too low to eliminate unemployment) was constrainedfurther by the Gramm-Rudman Amendment that promised to work toward a budgetbalance.

The economysuffered from weak growth and relatively high unemployment over most of thisperiod. Then, suddenly, economic growth picked up speed during the Clintonadministration; indeed it grew so fast that it produced a budget surplus (astax revenues boomed) that lasted for nearly three years (the first sustainedsurplus since 1929!). President Clinton actually predicted at the time that thebudget surplus would continue for at least 15 more years, and that alloutstanding Federal government debt would be retired (for the first time since1837).

Note thatthis was not accomplished by reversing the current account deficit—whichactually grew. How could the US run a current account deficit and a government budget surplus? Only byrunning a sustained private sector deficit. Indeed, from 1996 until 2007 the USprivate sector ran a budget deficit every year except during the recession ofthe early 2000s. At times, the domestic private sector deficit reached 6% ofGDP (meaning that for every Dollar of US national income, the private sectorspent $1.06. With such a large “flow” deficit, the stock of private sector debt grewrapidly—both in nominal terms and as a ratio to GDP. By 2007, total US debtreached five times GDP (versus three times GDP in 1929 on the verge of theGreat Depression). This huge debt implied a big debt burden—the portion ofincome that had to be devoted to servicing debt. When the economy collapsed in2007, a private sector surplus finally returned (the turn-around from private deficitsto private surpluses amounted to 8% of GDP—a huge reversal that removedapproximately $1 trillion of spending from the economy)—and the governmentbudget deficit grew rapidly to 10% of GDP. Even as the private sector cut downits spending, it was forced to default on debts run up since the Clintonperiod. A wave of bankruptcies and home foreclosures resulted that drove theeconomy into a deep recession and financial crisis that spread around theworld.

Next week: a budget stance to promote growth.

Bill Black Chats with Dylan Ratigan: Firedoglake Book Salon This Afternoon

Don’t miss William K. Black on today’s Firedoglake book salon. Professor Black will be chatting with Dylan Ratigan about his new book, Greedy Bastards: How We Can Stop Corporate Communists, Banksters, and Other Vampires from Sucking America Dry. The chat begins at 5:00 p.m. (EST). Click here to watch the chat.

In the meantime, you can read Professor Black’s review of Dylan’s book below.

Dylan Ratigan is well positioned to author a book,designed to be an enjoyable and informative read by normal humans, on theongoing financial crisis. He is the wunderkind who became Global Managing Editor for Corporate Finance ofBloomberg, the premier news service that specializes in finance, at anexceptionally young age. He was at CNBCwhile that network was hyping the housing bubble as a non-bubble offeringfantastic investment opportunities.

Now an anchor forMSNBC, Ratigan is a fierce critic of prominent politicians in both parties forwhat he views as their destructive policies and slavish efforts to aid thewealthiest and most politically powerful at the expense of the best interestsof America and its people. He ispassionate about these subjects and far less predictable than many of his peersbecause he is not a political partisan.

In finance, the most important question is why wesuffer recurrent, intensifying financial crises. That question is really two questions. Answering it requires that we determine whatcauses our crises and why we fail to learn from these crises, but instead makethe incentive structure ever more perverse after each crisis. Anyone from a finance background is likely toconclude that perverse incentives cause financial crises, so I was surprised byRatigan’s choice of book title (“Greedy Bastards”). I think that greed is unlikelyto have changed greatly over the last quarter century in which the U.S. hassuffered three recurrent, intensifying financial crises.

Idon’t call people bastards, even the self-made ones, because my mother reactedpoorly to Speaker Wright referring to me as the “red-headed SOB.” Ratigan’s view on these points turns out to be similar to mine. He arguesthat the issue is not greed, but perverse incentives. When CEOs haveincentives adverse to the public and their customers they tend to act on thoseincentives and harm the public and their customers. This observation isone of those essential points so often overlooked by writers about this crisis. A CEOs’ principal function is creating, monitoring, and adjusting thecorporation’s incentive structures. There is a massive businessliterature on this function and CEOs uniformly believe that incentivestructures for officers and employees are critical in shaping their behavior.

There is only one (disingenuous)exception to this rule – when officers and employees act criminally because theCEO has created perverse incentive structures. Suddenly, the CEO isshocked that his officers and employees acted criminally in response to theCEO’s incentive structures that encourage criminal conduct. Ratiganfocuses on precisely this exception. Anyone that has had the misfortuneto listen to compulsory business ethics training by his or her employer willhave learned that the key is the “tone at the top” set by the CEO. True,but that always ends the discussion. No employee is going to be trainedby his employer as to what to do when the tone at the top set by the CEO ispro-fraud.

As Ratigan demonstrates,our most elite financial CEOs typically created and maintained grotesquelyperverse incentive structures that encouraged their officers and employees aswell as “independent” professionals to act criminally in a manner that harmedcustomers, the public, and shareholders – but made the controlling officerswealthy. Is there any CEO of a lender incapable of understanding that whenthe loan officers and brokers’ compensation depends on volume and yield – notquality – the result will be catastrophic? Is there any CEO of a lenderincapable of understanding that if the loan brokers’ fees depend as well on thereported debt-to-income and loan-to-value ratios and the broker ispermitted to make liar’s loans the result will be that the brokers will engagein endemic, severe inflation of the borrowers’ incomes and their homes’appraised values? Is there any reader that doubts that the CEOs intendedto produce precisely what their perverse incentives were certain toproduce? A CEO cannot send a memo to 50,000 loan brokers instructing themto inflate appraisals and use liar’s loans to inflate the borrowers incomes’but he can, and does, send the same message through his compensationsystem. Each of these perverse incentives produces precisely the resultthat the CEOs expected and desired.

Ratigan gets right twoof the essentials to understanding why we suffer recurrent, intensifyingfinancial crises. First, cheating has become the dominant strategy infinance. Second, cheating is dominant because finance CEOs create suchintensely perverse incentives that fraud becomes endemic. The BusinessRoundtable (the largest100 U.S. corporations), had to react to the Enron erafrauds. It chose as its spokesperson a CEO who embodied the best ofAmerican big business. This was the response he gave to Business Week whentheir reporter asked why so many top corporations engaged in accounting controlfraud:

“Don’t just say: “If you hit this revenuenumber, your bonus is going to be this.” It sets up an incentive that’soverwhelming. You wave enough money in front of people, and good people will dobad things.”

How did the CEO knowabout the “overwhelming” effect of creating incentives so perverse that theywould routinely cause “good people [to] do bad things”? He knew becausehe directed and administered such a perverse compensation system. An SECcomplaint would soon identify that compensation system as driving accountingcontrol fraud at his firm. His name was Franklin Raines, CEO of FannieMae.

What Ratigan does in this book that differs soimportantly, and accurately, from nearly every other account of the crisis by aprominent writer is to say in plain English that our most elite financialinstitutions caused the crisis, that they did so because their controllingofficers caused them to cheat, and that the senior officers cheated their ownshareholders for the purpose of becoming wealthy.

Ratigan shows that theself-described “productive class” is actually a group dominated by “greedybastards” who win by cheating. As GeorgeAkerlof and Paul Romer said in their famous 1993 article (“Looting: theEconomic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit”), accounting fraud is a “surething.” Ratigan shows that while lootingbegins with accounting fraud it ends with tax fraud, political domination andscandal by the wealthy frauds, and crony capitalism. Indeed, Ratigan shows how far we have fallensince 1993. Fraudulent CEOs who controlsystemically dangerous institutions (SDIs) can now become wealthy by looting,cause the SDI to become insolvent, get bailed out by their political lackeys,resume looting, pay virtually no federal income tax, and do so with nearlycomplete immunity from prosecution. Heshows that rather than being “productive”, the greedy bastards are destroyingAmerica’s middle and working classes, hollowing out our economy, and destroyingwealth and employment.

Comments Off on Bill Black Chats with Dylan Ratigan: Firedoglake Book Salon This Afternoon

Posted in Uncategorized, William K. Black

Tagged dylan ratigan, William K. Black

Marshall Auerback discusses the Euro on the Lang and O’Leary Exchange. Watch it here.

Bill Moyers Essay: Occupying a Cause

The first episode of Bill Moyers’ new TV, Moyers & Company, features our own William K. Black and the Occupy Wall Street movement. Click here for local listings.

.

Comments Off on Bill Moyers Essay: Occupying a Cause

Posted in Uncategorized, William K. Black

Tagged William K. Black