In this blog we are going to begin to build the necessary foundation to understand modern money. Please bear with us. It may not be obvious, yet, why this is important. But you cannot possibly understand the debate about the government’s budget (and critique the deficit hysteria that has gripped our nation across the political spectrum from right to left) without understanding basic macro accounting. So, be patient and pay attention. No higher math or knowledge of intricate accounting rules will be required. This is simple, basic, stuff. It is a branch of logic. But it is extremely simple logic.

A note on terminology: a simple table at the bottom of this post will define some terms that will be used throughout this Primer. You might want to refer to it first, then come back and read the blog.

One’s financial asset is another’s financial liability. It is a fundamental principle of accounting that for every financial asset there is an equal and offsetting financial liability. The checking deposit is a household’s financial asset, offset by the bank’s liability (or IOU). A government or corporate bond is a household asset, but represents a liability of the issuer (either the government or the corporation). The household has some liabilities, too, including student loans, a home mortgage, or a car loan. These are held as assets by the creditor, which could be a bank or any of a number of types of financial institutions including pension funds, hedge funds, or insurance companies. A household’s net financial wealth is equal to the sum of all its financial assets (equal to its financial wealth) less the sum of its financial liabilities (all of the money-denominated IOUs it issued). If that is positive, it has positive net financial wealth.

Inside wealth vs outside wealth. It is often useful to distinguish among types of sectors in the economy. The most basic distinction is between the public sector (including all levels of government) and the private sector (including households and firms). If we were to take all of the privately-issued financial assets and liabilities, it is a matter of logic that the sum of financial assets must equal the sum of financial liabilities. In other words, net financial wealth would have to be zero if we consider only private sector IOUs. This is sometimes called “inside wealth” because it is “inside” the private sector. In order for the private sector to accumulate net financial wealth, it must be in the form of “outside wealth”, that is, financial claims on another sector. Given our basic division between the public sector and the private sector, the outside financial wealth takes the form of government IOUs. The private sector holds government currency (including coins and paper currency) as well as the full range of government bonds (short term bills, longer maturity bonds) as net financial assets, a portion of its positive net wealth.

A note on nonfinancial wealth (real assets). One’s financial asset is necessarily offset by another’s financial liability. In the aggregate, net financial wealth must equal zero. However, real assets represent one’s wealth that is not offset by another’s liability, hence, at the aggregate level net wealth equals the value of real (nonfinancial) assets. To be clear, you might have purchased an automobile by going into debt. Your financial liability (your car loan) is offset by the financial asset held by the auto loan company. Since those net to zero, what remains is the value of the real asset—the car. In most of the discussion that follows we will be concerned with financial assets and liabilities, but will keep in the back of our minds that the value of real assets provides net wealth at both the individual level and at the aggregate level. Once we subtract all financial liabilities from total assets (real and financial) we are left with nonfinancial (real) assets, or aggregate net worth.

Net private financial wealth equals public debt. Flows (of income or spending) accumulate to stocks. The private sector accumulation of net financial assets over the course of a year is made possible only because its spending is less than its income over that same period. In other words, it has been saving, enabling it to accumulate a stock of wealth in the form of financial assets. In our simple example with only a public sector and a private sector, these financial assets are government liabilities—government currency and government bonds. These government IOUs, in turn, can be accumulated only when the government spends more than it receives in the form of tax revenue. This is a government deficit, which is the flow of government spending less the flow of government tax revenue measured in the money of account over a given period (usually, a year). This deficit accumulates to a stock of government debt—equal to the private sector’s accumulation of financial wealth over the same period. A complete explanation of the process of government spending and taxing will be provided in the weeks and months to come. What is necessary to understand at this point is that the net financial assets held by the private sector are exactly equal to the net financial liabilities issued by the government in our two-sector example. If the government always runs a balanced budget, with its spending always equal to its tax revenue, the private sector’s net financial wealth will be zero. If the government runs continuous budget surpluses (spending is less than tax receipts), the private sector’s net financial wealth must be negative. In other words, the private sector will be indebted to the public sector.

We can formulate a resulting “dilemma”: in our two sector model it is impossible for both the public sector and the private sector to run surpluses. And if the public sector were to run surpluses, by identity the private sector would have to run deficits. If the public sector were to run sufficient surpluses to retire all its outstanding debt, by identity the private sector would run equivalent deficits, running down its net financial wealth until it reached zero.

Rest of world debts are domestic financial assets. Another useful division is to form three sectors: a domestic private sector, a domestic public sector, and a “rest of the world” sector that consists of foreign governments, firms, and households. In this case, it is possible for the domestic private sector to accumulate net claims on the rest of the world, even if the domestic public sector runs a balanced budget, with its spending over the period exactly equal to its tax revenue. The domestic sector’s accumulation of net financial assets is equal to the rest of the world’s issue of net financial liabilities. Finally, and more realistically, the domestic private sector can accumulate net financial wealth consisting of both domestic government liabilities as well as rest of world liabilities. It is possible for the domestic private sector to accumulate government debt (adding to its net financial wealth) while also issuing debt to the rest of the world (reducing its net financial wealth). In the next section we turn to a detailed discussion of sectoral balances.

Basics of sectoral accounting, relations to stock and flow concepts. Let us continue with our division of the economy into three sectors: a domestic private sector (households and firms), a domestic government sector (including local, state or province, and national governments), and a foreign sector (the rest of the world, including households, firms, and governments). Each of these sectors can be treated as if it had an income flow and a spending flow over the accounting period, which we will take to be a year. There is no reason for any individual sector to balance its income and spending flows each year. If it spends less than its income, this is called a budget surplus for the year; if it spends more than its income, this is called a budget deficit for the year; a balanced budget indicates that income equalled spending over the year.

From the discussion above, it will be clear that a budget surplus is the same thing as a saving flow and leads to net accumulation of financial assets. By the same token, a budget deficit reduces net financial wealth. The sector that runs a deficit must either use its financial assets that had been accumulated in previous years (when surpluses were run), or must issue new IOUs to offset its deficits. In common parlance, we say that it “pays for” its deficit spending by exchanging its assets for spendable bank deposits (called “dis-saving”), or it issues debt (“borrows”) to obtain spendable bank deposits. Once it runs out of accumulated assets, it has no choice but to increase its indebtedness every year that it runs a deficit budget. On the other hand, a sector that runs a budget surplus will be accumulating net financial assets. This surplus will take the form of financial claims on at least one of the other sectors.

Another note on real assets. A question arises: what if one uses savings (a budget surplus) to purchase real assets rather than to accumulate net financial assets? In that case, the financial assets are simply passed along to someone else. For example, if you spend less than your income, you can accumulate deposits in your checking account. If you decide you do not want to hold your savings in the form of a checking deposit, you can write a check to purchase—say—a painting, an antique car, a stamp collection, real estate, a machine, or even a business firm. You convert a financial asset into a real asset. However, the seller has made the opposite transaction and now holds the financial asset. The point is that if the private sector taken as a whole runs a budget surplus, someone will be accumulating net financial assets (claims on another sector), although activities within the private sector can shift those net financial assets from one “pocket” to another.

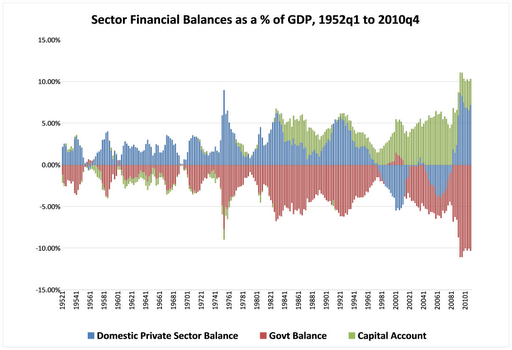

Conclusion: One sector’s deficit equals another’s surplus. All of this brings us to the important accounting principle that if we sum the deficits run by one or more sectors, this must equal the surpluses run by the other sector(s). Following the pioneering work by Wynne Godley, we can state this principle in the form of a simple identity:

Domestic Private Balance + Domestic Government Balance + Foreign Balance = 0

For example, let us assume that the foreign sector runs a balanced budget (in the identity above, the foreign balance equals zero). Let us further assume that the domestic private sector’s income is $100 billion while its spending is equal to $90 billion, for a budget surplus of $10 billion over the year. Then, by identity, the domestic government sector’s budget deficit for the year is equal to $10 billion. From the discussion above, we know that the domestic private sector will accumulate $10 billion of net financial wealth during the year, consisting of $10 billion of domestic government sector liabilities.

As another example, assume that the foreign sector spends less than its income, with a budget surplus of $20 billion. At the same time, the domestic government sector also spends less than its income, running a budget surplus of $10 billion. From our accounting identity, we know that over the same period the domestic private sector must have run a budget deficit equal to $30 billion ($20 billion plus $10 billion). At the same time, its net financial wealth will have fallen by $30 billion as it sold assets and issued debt. Meanwhile, the domestic government sector will have increased its net financial wealth by $10 billion (reducing its outstanding debt or increasing its claims on the other sectors), and the foreign sector will have increased its net financial position by $20 billion (also reducing its outstanding debt or increasing its claims on the other sectors).

It is apparent that if one sector is going to run a budget surplus, at least one other sector must run a budget deficit. In terms of stock variables, in order for one sector to accumulate net financial wealth, at least one other sector must increase its indebtedness by the same amount. It is impossible for all sectors to accumulate net financial wealth by running budget surpluses. We can formulate another “dilemma”: if one of three sectors is to run a surplus, at least one of the others must run a deficit.

No matter how hard we might try, we cannot all run surpluses. It is a lot like those children at Lake Wobegone who are supposedly above average. For every kid above average there must be one below average. And, for every deficit there must be a surplus.

Notes on Terms. Throughout this primer we will adopt the following definitions and conventions:

The word “money” will refer to a general, representative unit of account. We will not use the word to apply to any specific “thing”—ie a coin or central bank note.

Money “things” will be identified specifically: a coin, a bank note, a demand deposit. Some of these can be touched (paper notes), others are electronic entries on balance sheets (demand deposits, bank reserves). So, “money things” is simply short-hand for “money denominated IOUs”.

A specific national money of account will be designated with a capital letter: US Dollar, Japanese Yen, Chinese Yuan, UK Pound, EMU Euro.

The word currency is used to indicate coins, notes, and reserves issued by government (both by the treasury and the central bank). When designating a specific treasury or its bonds, the word will be capitalized: US Treasury; US Treasuries.

Net financial assets are equal to total financial assets less total financial liabilities. This is not the same as net wealth (or net worth) because it ignores real assets.

An IOU (I owe you) is a financial debt, liability, or obligation to pay, denominated in a money of account. It is a financial asset of the holder. There can be physical evidence of the IOU (for example, written on paper, stamped on coin) or it can be recorded electronically (for example, on a bank balance sheet).