By Dan Kervick

When economists talk about the role of government in economic recovery, they often focus on the question of whether or not we need more economic stimulus. They ask whether the government should temporarily change its fiscal policies – its taxing and spending decisions – to add some additional publicly financed spending to the economy and help jolt the private sector back to life. But this fixation on countercyclical stimulus as almost the sole economic purpose of fiscal policy can really distort our understanding of the many ways in which public spending supports economic health. When we take a broader view of the current scene we find that, in addition to its failure to provide adequate countercyclical stimulus, the public arm of our economy is dropping the ball quite dramatically in other ways.

Government participation in the economy does not just promote private sector activity. Government is itself a large, diverse and important sphere of economic enterprise. Our federal, state and local governments produce and deliver important goods and service, things that people want and need, and that they have asked their representatives to create and maintain. And governments employ millions of people in income-earning positions to carry out all of this production. Ordinarily, we would expect that as a society grows, government will grow commensurately along with everything else. As our population grows and private enterprises proliferate, we need more schools and teachers, more courthouses and police stations, more public parks, more inspectors and regulators, more paved roads and street lights, and more government clerical workers. So while it is true that government spending also stimulates additional economic activity in the private sector – just as any economic enterprise stimulates economic activity in the other enterprises it touches and affects – it is also true that the public enterprises governments oversee and the tasks governments perform are all by themselves an important component of overall economic activity.

The part of government spending that is devoted to purchases made in the production of goods and services is called “consumption and gross investment” in the National Income and Product Accounts maintained by the BEA, and it amounts to about 15% to 20% of GDP. Government consumption and gross investment (CGI) can be contrasted with other forms of government spending that do not contribute to GDP, such as transfer payments to the public under social insurance programs like Social Security and unemployment insurance programs. As an example of the contrast, note that the money the federal government spends to run the Social Security Administration is part of government CGI. The money the Social Security Administration actually pays out to retirees, however, is classified as a transfer payment.

Paul Krugman has called our attention to what he calls our “amazing shrinking government”. Krugman compares government CGI in the Great Recession to CGI following the 2001 recession. In both cases we see an initial surge in government spending as a result of some federal stimulus. And following the stimulatory phase of the 2001 recession, the pace of CGI declined only in the sense that it grew at a slower rate. But after the stimulus that was enacted in 2009 began to wear off in 2011, public enterprise did not just begin to grow more slowly. It declined precipitously. Krugman sizes up the impact:

“How big a deal is this? Government consumption and investment is about $3 trillion; if it had grown as fast this time as it did in the Bush years, it would be 12 percent, or $360 billion, higher. Given a multiplier of more than one, which is what the IMF among others now thinks reasonable under current conditions, that ends up meaning GDP something like $450 billion higher, which is 3 percent — and an unemployment rate 1.5 points lower.”

“So fiscal austerity is the difference between where we are now and an unemployment rate not much above 6 percent. It’s a policy disaster.”

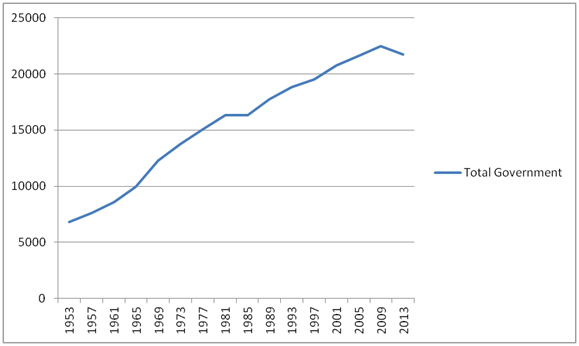

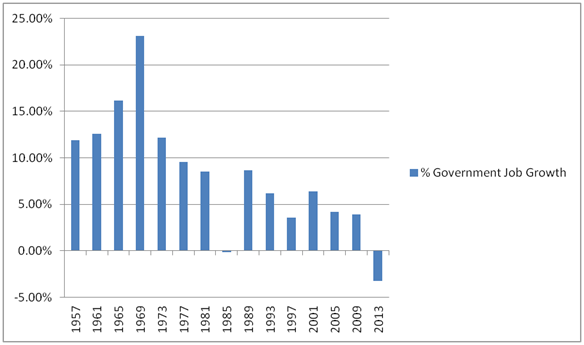

To get a clearer picture of this unfolding disaster, and just how large and unprecedented is the collapse in public enterprise during the past few years, let’s shift attention to jobs rather than GDP. The first chart below shows total government jobs – federal, state and local – in January of each of the presidential inauguration years since 1953. The second chart shows the percentage increases from January of one inaugural year to January of the next inaugural year, with the first entry – marked “1957” – measuring the 1953-57 period. (A hat tip is due here to the commentator who posts as “Anne” at Mark Thoma’s Economist’s View, for directing me to these statistics.)

Note the steady increase in government employment over this period, under both political parties, except for two administrations: the Reagan administration and the Obama administration. The 3.25% decrease that has occurred under Obama is actually unprecedented over the past 60 years. Obama’s sometime political hero Ronald Reagan, who famously declared government to be our enemy and carried out what is often seen as an anti-government “revolution” in the public sphere of the economy, managed only a 0.15 % reduction.

This is really something of a catastrophe. We are shutting down government activity and dismantling the capacity of public enterprise just when we need it most. Recently, a number of Democratic pundits have taken to trumpeting these dramatic drops in government spending and employment – but not to decry them. Instead the preferred political spin seems to turn in the direction of embracing the austerity agenda, while holding Barack Obama up as a paragon of tight budgets and abstemious fiscal virtue. Obama, we can recall, told us government must shrink because we are “out of money”. But notice how absurd it would be if the leaders of private sector industry were to say that the private sector economy has to shrink because it is out of money. Everybody recognizes that if our economy is to grow and progress, private enterprise needs to spend and invest, and that the means of financing are created along with the initiatives that are financed. In the case of government, the financial constraint is even less relevant, since a government that controls the very currency which is the monetary foundation of the whole system of financial assets denominated in that currency can never have an inherent financial constraint due to a lack of money.

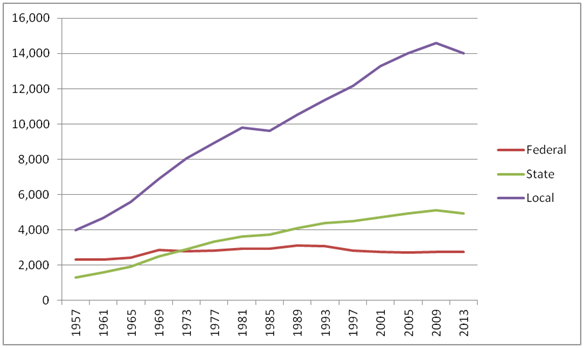

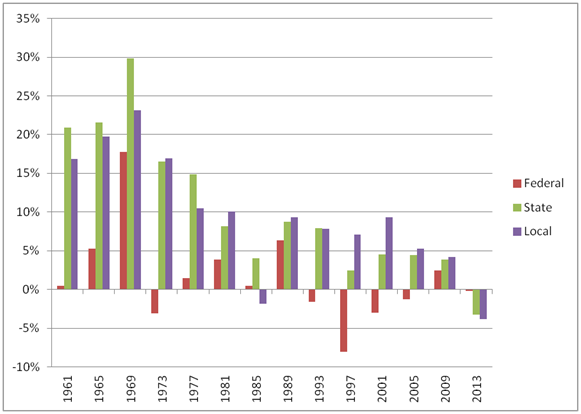

The next two charts give us a clearer and more detailed picture of what has happened during the Obama administration. The figures for total government employment and net change in government employment are now analyzed into federal, state and local components.

We see here that the dramatic decline in government spending during this period is not mainly due to a decline in federal government jobs, but to extremely sharp drops in state and local government jobs. In the local government sector, only the first term of the Reagan administration saw a similar drop in jobs, although that drop was not as large as the Obama administration drop. In the area of state government employment, on the other hand, the Obama administration collapse is absolutely unprecedented over the past 60 years. No other four-year presidential term saw a net drop in state government employment. But state government jobs have fallen by 3.3% under Obama.

None of this should be completely surprising, since the bipartisan political landscape for the past two years has been dominated by a growing turn toward austerity, talk of budgetary “grand bargains,” fiscal cliffs, sequestration, etc. Both parties seem determined to shrink the role of government in our economy. Needless to say, not only is the absolute decline in public enterprise very unusual, it runs contrary to the great progressive tradition supporting an active role for government in our economy. This tradition, which took shape most decisively under the two Roosevelts, long characterized the dominant outlook of the Democratic Party. Newer Democrats, however, have turned toward the destruction of government. Notice by way of evidence the dramatic drops in the federal government sector during the two terms of the Clinton administration.

Please note that the issue here is not so much whether the government gets bigger as a share of GDP. The point is that as the economy grows, we would ordinarily see government CGI and jobs grow at about the same rate as the rest of the economy, even if government was becoming no greater or less a share of that economy. As I mentioned earlier, government CGI plays two roles. On the one hand, it stimulates complementary economic activity in the private sector. Matt Yglesias makes that point in a recent post and pointedly pushes back against the “crowding out” camp:

Had there been more building of military equipment and schools, would that have been fully offset by less private consumption? By less business investment? By fewer exports? It seems to me that there would have been more business investment since private firms would have invested in the capacity to meet those increased orders. And there would have been more household consumption, since people would have had higher incomes.

But again it is important to remember that government consumption and gross investment are not just important because of the boost they give to additional private sector activity. Government CGI is all by itself a hugely important part of our economy. At the state level especially, that part of our economy is now shrinking in a dangerous and harmful way. In my state of New Hampshire, for example, the state’s transportation commissioner has reported on the dire condition of many of the state’s roads and bridges:

Since he was appointed as the New Hampshire transportation commissioner in 2011, Chris Clement has become an evangelist in spreading the word about the urgent need for investment in the state’s roads and bridges.

To be exact, that’s 4,559 miles of state-maintained roads and 2,143 state-owned bridges. Clement and the DOT estimate there are 1,565 miles, or 37 percent, of roads in poor condition, and that includes 970 miles of unnumbered state roads that currently receive no maintenance at all due to budget priorities. There are also 140 so-called “red list” bridges, which require regular inspections due to their degraded state.

“We have been talking about this for some time,” said Clement, who served as deputy commissioner before replacing George Campbell.

Clement has spoken to business groups across the state during the past year about the vital economic need for a more robust effort to maintain and repair the state’s roads.

“This is a nationwide problem and we have tried to take the emotion out of it,” he said. “I believe we have made our message clear and concise.”

State governments, unlike the federal government, do not manage the nation’s monetary system and they therefore operate under a revenue constraint that they cannot fully control. So if state spending and employment are collapsing as a result of falling revenues, the federal government should be rushing in to support state budgets until revenues return to normal and states can self-fund.

Now, not everyone sees the need for reversing the collapse in public enterprise. Conservative commentator Larry Kudlow recently argued that the collapse is actually a good thing:

Which leads me to another key point: Even with the fourth-quarter contraction, the latest GDP report shows that falling government spending can coexist with rising private economic activity.

This is an important point in terms of the upcoming spending sequester. Lower federal spending, limited government, and a smaller spending-to-GDP ratio will be good for growth. The military spending plunge will not likely be repeated. But by keeping resources in private hands, rather than transferring them to the inefficient government sector, the spending sequester is actually pro-growth.

Of course, the numbers don’t at all bear out this supposed pro-growth message, because government CGI is itself part of the national product. Naturally, if the government stops producing things of value, the private sector will pick up at least some of the slack, but the private sector is not the whole economy, and stagnant GDP growth due to a collapse of government CGI is stagnant GDP growth tout court. Here we see that Kudlow hates what the government does so much that he is willing to accept a lower level of overall national product if the private sector component of that product increases. That’s the sort of fanaticism we have seen lately in our public discourse.

Government is a productive enterprise. We are insanely destroying much of that enterprise – and along with it the jobs, incomes and forms of national wealth public enterprise creates – in a misguided push toward austerity. There is no hope that the private sector can itself perform most of these governmental functions, nor would we want it to do so in most cases since the result would be to turn over vitally important and democratically controlled systems to private ownership and corporate domination. What in the world are we doing to ourselves? The government’s capacity to spend is one of the few things we directly control during hard economic times. The path of austerity and public enterprise destruction is madness of the kind only puritanical government-haters like Kudlow could celebrate.

Robert Reich recently wrote in celebration the 100th anniversary of what he calls “America’s first progressive revolution”:

The 1880s and 1890s had been the Gilded Age, the time of robber barons, when a small number controlled almost all the nation’s wealth as well as our democracy, when poverty had risen to record levels, and when it looked as though the country was destined to become a moneyed aristocracy.

But almost without warning, progressives reversed the tide. Teddy Roosevelt became president in 1901, pledging to break up the giant trusts and end the reign of the “malefactors of great wealth.” Laws were enacted protecting the public from impure foods and drugs, and from corrupt legislators.

Following the progressive revolution of which Reich speaks, we saw the flowering of progressive government during the New Deal period, a bold embrace of public empowerment which initiated activist trends in public self-determination whose momentum carried through during the next several decades of spectacular national development, broadening prosperity and progress. A renewed commitment to public enterprise progressivism can shake off our current stagnation, and launch a new era of full employment, social progress and rising hopes.

Pingback: The Dangerous Collapse of Public Enterprise | Real Economy Notes | Scoop.it

Pingback: The Dangerous Collapse of Public Enterprise

Pingback: Reserve Balance Misconceptions | New Economic Perspectives

Pingback: I Have Seen the Next Big Thing, and it is Mariana Mazzucato | New Economic Perspectives