By William K. Black

Associate Professor of Law and Economics, University of Missouri-Kansas City

This is my third essay commenting on Bo Cutter’s essay defending Treasury Secretary Geithner.

The prior installments can be found here and here.

Bo was a managing partner of Warburg Pincus, a major global private equity firm and led President Obama’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) transition team. He was Bob Rubin’s deputy at the National Economic Council and Deputy Director of OMB for Carter. Bo’s defense of Geithner ends with his view that Geithner emerged as The Last Action Hero:

Tim Geithner acted. He acted at the moment action was required … with the full knowledge that he would face exactly what he is now facing.

Get off his back.

This essay provides an alternative view. I have written elsewhere of why Geithner’s actions once he became Treasury Secretary were so harmful. This essay discusses his failures to act when he was President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY). First, Bo concedes that Geithner did not act “at the moment action was required” – he was years late and trillions of dollars short.

[T]his crisis was long in coming and it was a totally integrated failure of intellectual traditions, global macro-economic imbalances, government policy making, regulatory supervision, financial sector greed, incomprehensible boards of directors’ absences without leave, and breath-taking management short-sightedness. No one and no institution put together an understanding of the set of factors that triggered this particular debacle. Tim [Geithner] is included in this “no one,” but so is everyone else.

I think the last two years have revealed the single largest failure of senior management in the financial sector, and of the board system in American history. I think I am correct in saying that there was not a single independent director in America who stood up on this issue. I do not understand why every board of every institution that failed was not asked to resign immediately. But I guess the answer is “when you are up to your ass in alligators, it is hard to think about draining the swamp.” Geithner had other things to do at that moment than settle scores.

In fact, by 2006 and early 2007 everyone thought we were headed to a cliff, but no one knew when or what the triggering mechanism would be. The capital market experts I was listening to all thought the banks were going crazy, and that the terms of major loans being offered by the banks were nuttiness of epic proportions.

Bo admits that even the most ideologically-blinded theoclassical economists (his phrase is “failure of intellectual traditions”) knew “we were headed to a cliff” by 2006. “Everyone,” including “the capital market experts” knew that “the banks were going crazy.” Moreover, the experts all knew that the banks were not merely “crazy” but farblondget (a Yiddish term literally meaning “lost” but with the connotation of insanely lost: as in I tried to drive from Kansas City, Missouri to Lawrence, Kansas and 28 hours later it began to dawn on me that I might be lost because all the signs were in Spanish). The banks were so farblondget that Bo aptly describes the “terms of major loans” as “nuttiness of epic proportions.” In my first essay I explained that this pattern demonstrates that there was an epidemic of what white-collar criminologists term “accounting control fraud.” Honest banks would not make loans on such terms because they were suicidal. The housing bubble had already stopped inflating by 2006 and the nonprime specialty lenders were blowing up.

The FBI warned publicly in September 2004 that an “epidemic” of mortgage fraud was developing and that it would cause a crisis if it were not stopped. It later emphasized that 80% of mortgage fraud losses occurred when lender personnel were involved in the frauds. Geithner, Bernanke, Paulson, and Greenspan took no effective action against the growing epidemic – even when Fed Member Ned Gramlich warned them of the housing bubble and urged Greenspan to send in the examiners to contain the raging problems in nonprime lending. Geithner, Bernanke, and Greenspan bear special culpability for their refusal to act against the epidemic of accounting control fraud because (1) Congress mandated that the Fed hold hearings on nonprime loans (which revealed (a) extremely high delinquencies, (b) frequent predation, and (c) widespread mortgage fraud involving lender personnel), and (2) the Fed had unique statutory authority to regulate otherwise unregulated mortgage lenders. The Fed refused to use its authority despite Gramlich’s warnings, the hearing record demonstrating widespread lender abuses and fraud, the rapidly inflating housing bubble, the warnings of non-theoclassical economists, and the FBI’s 2004 warnings.

Bo is correct, “the crisis was long in coming.” Bo is incorrect in claiming that “no one” saw it coming. Many others did and they warned Geithner and Bernanke years before the crisis while they had ample time to act and prevent the crisis from occurring. (Here, I will not set out the number of non-theoclassical economists that got it right. We all know that Geithner and Bernanke still ignore these voices. For the purposes of this essay I discuss only a few warnings we know they received – and ignored.) Bernanke and Geithner held key positions during the long period in which the crisis grew. Geithner was President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from October 23, 2003 until President Obama chose him as his Treasury Secretary. In that role he was supposed to serve as the lead regulator of many of the nation’s largest bank holding companies. He was an abject failure as a regulator, and a major cause of the “economy falling off the cliff.” Bernanke held prominent positions in the Bush administration from 2002 through the administration’s end (as a Fed member, Chair of Bush’s Council of Economic Advisors, and then his return to the Fed as its Chair). He was an abject failure as a regulator and as Bush’s economic advisor.

Bo does not recognize that his account of the industry’s long, downward spiral into an epidemic of control fraud while Geithner and Bernanke stood silent and impotent while closing their ears to the timely warnings of the coming crisis constitutes a scathing critique of Geithner’s and Bernanke’s failures as regulators. He literally has zero expectation that Geithner and Bernanke would do anything useful as regulators before the global crisis raged and he imposes no accountability on them for failing to act. Bo was Carter’s Deputy head of OMB and Obama’s transition team leader for OMB. OMB is, in every administration, the institutional enemy of vigorous regulation and vigorous regulators. (It was OMB that threatened to make a criminal referral against Bank Board Chairman Gray on the “grounds” that he was closing too many insolvent S&Ls.)

If we continue to have low expectations for our regulators, we will continue to have failed regulation. Let us reprise Bo’s facts, using a radically different standard under which we expect senior regulators making roughly $400,000 annually (Geithner as FRBNY President) and roughly $200,000 annually (Bernanke as Fed Chairman) to take regulatory action against unsafe and unlawful practices so obviously disastrous that “everyone thought we were headed to a cliff.” When capital market analysts “all thought the banks were going crazy, and that the terms of major loans being offered by the banks were nuttiness of epic proportions” even minimally competent regulators would order them to cease such lending immediately and make criminal referrals.

As two of the most important regulatory leaders, Geithner and Bernanke had the duty (and the power) to fix the broken regulatory system. Bo makes the point that “this crisis was long in coming” and arose from the “failure” of “government policy making [and] regulatory supervision.” Bernanke and Geithner were leaders in shaping those failed government policies and regulatory supervision. Those failures continued for over five years under their leadership and still have not been fixed.

In addition to Bo’s demonstration (1) that Geithner and Bernanke failed to order an end to lending practices they knew were suicidal (and should have known were fraudulent) and (2) their failure to fix their failed regulatory agency and their failed governmental policies, he shows (3) that they also failed to deal with endemic failure of bank managers and directors.

I think the last two years have revealed the single largest failure of senior management in the financial sector, and of the board system in American history. I think I am correct in saying that there was not a single independent director in America who stood up on this issue. I do not understand why every board of every institution that failed was not asked to resign immediately. But I guess the answer is “when you are up to your ass in alligators, it is hard to think about draining the swamp.” Geithner had other things to do at that moment than settle scores.

Bo asks why the directors of every failed institution were “not asked to resign immediately.” That’s a necessary but incomplete question. The first question is why senior regulatory leaders, including Geithner and Bernanke, did not act to end “the single largest failure of senior management” and the failure of every “single independent director.” Real regulators don’t wait for the bank to fail before acting against the largest failure of senior management in history. The second question is who failed to ask for the boards (and the officers) to “resign immediately” upon the failure of the banks. Bernanke and Geithner are two of the regulatory leaders that should have adopted policies mandating those resignations.

The third question is when these banks “failed.” Bo implies that they failed in late 2008 and 2009, but the facts he presents demonstrate that they had failed years before. When banks made “major loans” in 2006 on terms that “were nuttiness of epic proportions” they made themselves insolvent. Bo’s colorful phrase means that the yield on the loans was not remotely adequate to allow the lender to earn a profit because so many of the loans would default as soon as the housing bubble stalled. If the lenders, as required by generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), established adequate loss reserves to cover those losses from the coming wave of defaults they would report massive losses and be forced to recognize that they were insolvent. Instead, even as they made loans on terms of ever increasing “nuttiness of epic proportions,” which required record high loss reserves they instead reduced their already grossly inadequate loss reserves to record low levels so that they could report (fraudulent) profits. A.M. Best warned in its 2005 report that “the industry’s reserves-to-loan ratio has been setting new record lows for the past four years.” These “profits” led to enormous “performance” bonuses to the senior executives running the control frauds.

The same A.M. Best report made a point that has great importance for considering Geithner’s failures as a regulator and Bernanke’s failures as both a regulator and as Bush’s chief economic advisor: a “10-year record low number of problem banks for the quarter results ended Sept. 30, 2005.” The regulators determine which banks are “problems.” It sounds like good news, but the finding is actually proof of a catastrophic regulatory failure. The number of failed – not simply “problem” – banks was surging but the regulators were blind to the epidemic of accounting control fraud that was masking their failures. The greatest value that banking regulators can add is to recognize the distinctive pattern of such accounting frauds and to close them at the earliest possible time.

Nonprime specialty lenders loan terms exhibited “nuttiness of epic proportions” well before 2006 and that made them insolvent well before 2006. “MBA [Mortgage Bankers’ Association] data show that interest-only and adjustable-rate mortgages made up 65% of new mortgages in 2004, up from 18% in 2003″ (February 27, 2006). The FBI’s September 2004 warning about the epidemic of mortgage fraud and coming crisis was spot on.

The nonprime specialty lenders, of course, did not report that they were insolvent when then made loans on terms certain to destroy the lenders. They followed the standard recipe for lenders optimizing accounting control fraud: extremely rapid growth, making exceptionally bad loans, extreme leverage, and providing only minimal loss reserves. This guaranteed that they would report record “income” in the short-term.

The fourth set of questions is where are the enforcement actions by the Fed to remove and prohibit the officers and directors that Bo confirms represent an endemic failure to comply with their fiduciary duties or safety and soundness, and where are the Fed enforcement actions to recover their bonuses and other fraudulent gains? The fifth question is where are the Fed’s criminal referrals against the accounting control frauds. Bo’s answer to this question is fully representative of big finance’s attitude towards the prosecution of elite white-collar criminals:

I do not understand why every board of every institution that failed was not asked to resign immediately. But I guess the answer is “when you are up to your ass in alligators, it is hard to think about draining the swamp.” Geithner had other things to do at that moment than settle scores.

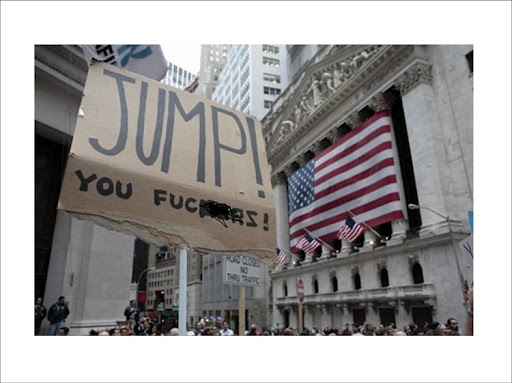

I write now from the perspective of one wearing both regulatory and white-collar criminology “hats.” When the industry has become an alligator-filled swamp draining that swamp is precisely what you need to do. The swamp is the “criminogenic environment” that creates perverse incentives that produce the alligators (control frauds) and gives them cover so that they can attack with impunity. You need to drain the swamp and you need to simultaneously target the biggest, “baddest” alligator. You tan his hide on the side of your shed and show that no alligator is too big to flail. Bo will not hold any financial elite accountable. He treats accountability – which is essential if we are to reduce the risk of future crises – as a shameful practice: “settling scores.” Is it any wonder that while we obtained felony convictions in over 1000 “priority” cases during the S&L debacle there has yet to be a single indictment of a senior manager of a large nonprime lender?

The sixth set of questions has to do with loss reserves. The banks’ loss reserves were unlawfully low in order to inflate income and the senior officers’ bonuses. The banks’ loss reserves were obscenely inadequate – often a small percentage of the actual losses. Instead of demanding that the banks add adequate loss reserves, Geithner and Bernanke acquiesced to legalized accounting fraud. They stood by while the industry extorted Congress and Congress extorted the accounting profession to reprise the disastrous Reagan era policy of covering up a financial crisis through accounting scams. The Fed, however, can use its supervisory powers to mandate adequate loss reserves regardless of whether the newly neutered GAAP requires adequate reserves. Geithner and Bernanke are refusing to use their supervisory powers to require banks to recognize their losses. Without honest accounting for losses virtually all supervisory powers are crippled.

If Geithner and Bernanke (or Greenspan) had acted as minimally competent regulators in response to the FBI’s September 2004 warnings the epidemic of accounting control fraud could have been contained and an acute financial crisis prevented. As late as 2006, they could have prevented over a trillion dollars in losses had they been effective regulators.

Geithner’s Self-fulfilling Prophecy of Regulatory Failure

The questions above arise from Bo’s indictment of the finance industry and implicit admissions as to Geithner’s and Bernanke’s recurrent failures. This essay concludes by asking the broader question of why Geithner failed so badly as a regulator. Geithner does not understand, or value, regulation or white-collar crime prosecutions. Consider three aspects of this that draw on his statements. First, he admits (see here and here) that he has never regulated even though one of his primary duties was to lead the examination and supervision of many of our nation’s largest bank holding companies.

Tim Geithner: I would just want to correct one thing. I’ve never been a regulator….

Second, he testified, in response to a question from Representative Ron Paul in 2009, that excessive regulation was among the fundamental problems leading to the crisis was:

Tim Geithner: We have parts of our system, which are overwhelmed by regulations. Overwhelmed by regulations. It wasn’t the absence of regulations that was the problem, it was despite the presence of regulations, and you have huge risk built up.

Third, he believes that regulators are helpless in the face of an inflating asset bubble. On March 6, 2008, Geithner offered this explanation for his failure to take any regulatory action against the housing bubble and the nonprime lending crisis: “I don’t believe that asset price and credit booms are preventable.” There is nothing as debilitating as believing that one is helpless. Geithner and Greenspan believed that they were helpless as regulators, which created a self-fulfilling prophecy of failure.

Fourth, Geithner’s testimony in response to Ron Paul’s questions indicates that he believes that, absent deposit insurance, there is no risk of “moral hazard” and no strong basis for regulation.

Because they’re vulnerable to runs, governments around the world have put in place insurance protections to protect the inside risks.

Because of the existence of those protections, you have to impose standards on them on leverage to protect against the moral hazard created by the insurance. That is a good economic case for regulation –

This is good theoclassical economics, which is to say it is devastatingly bad economics that has been repeatedly falsified by reality and by white-collar criminological research. Geithner has been taught that “private market discipline” prevents fraud absent government “interference” in the markets (e.g., deposit insurance) that removes the incentive of creditors to exercise discipline against fraud. It follows that financial derivatives pose no meaningful fraud risk and financial markets will be “efficient.” The problem is that accounting control fraud does not simply defeat private market discipline – it renders it perverse and creates a “Gresham’s dynamic” in which dishonest corporate officers and firms that cheat gain a competitive advantage and may drive honest actors from the marketplace. Enron, WorldCom, and the 80% of the nonprime specialty lenders that were unregulated have repeatedly shown that accounting control fraud can become endemic in industries that do not have government guarantees. Greenspan shared Geithner’s failure to understand how accounting control frauds work and why anti-regulation effectively decriminalizes the fraud and turns it into virtually a perfect crime.

Bo seeks to make light of Geithner’s critics by joking that we’re upset at Geithner’s being short of height. Our concern is that he is short of integrity, independence from Wall Street, and ability. Geithner knew that he had unlawfully failed to pay taxes. He also knew he could get away with not paying many of those taxes because the statute of limitations had run. The context of his moral challenge was an IRS audit in 2006 while he was President of the FRBNY. That is one of the most prestigious and senior regulatory positions in the world. Geithner had been highly compensated while working for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is where he failed to pay a substantial (but small relative to his wealth) amount of taxes. His compensation as FRBNY President (roughly $400,000 by 2007) placed him in the upper tiers of income. He was probably the most highly compensated regulator in the world. He chose not to pay the taxes he owed that were past the statute of limitations because he could get away with it. That’s the perfect circumstance to judge a person’s core integrity. He was already wealthy and could have paid the taxes without any meaningful sacrifice. He did not need the money to educate his kids or pay for their health care. He was simply greedy and willing to cheat if he could do so with impunity.

Geithner did not act as FRBNY President to protect the public. He wasn’t heroic, competent, or even honest. If Bo is correct and Geithner and Bernanke represent the very best of the leaders of the finance industry, then the inevitable conclusion is that we need to remove not only Geithner and Bernanke, but also clean the entire Stygian Stables that is Wall Street. That task is so large as to be a modern labor of Hercules.