By J. D. Alt

Why does it seem like there isn’t enough money to pay for the things we really need? The headlines are filled with stories about our nation’s “debt problem” and dire warnings about our impending “bankruptcy.” As an architect who fills his waking hours thinking up all kinds of wonderful things we could be building, I’m alarmed by the idea there isn’t enough money to pay for any of them. Before wasting more time dreaming, I had to find out: Is it really true? Are we really too poor to put America back to work making and building the things we need to maintain a prosperous nation?

Why does it seem like there isn’t enough money to pay for the things we really need? The headlines are filled with stories about our nation’s “debt problem” and dire warnings about our impending “bankruptcy.” As an architect who fills his waking hours thinking up all kinds of wonderful things we could be building, I’m alarmed by the idea there isn’t enough money to pay for any of them. Before wasting more time dreaming, I had to find out: Is it really true? Are we really too poor to put America back to work making and building the things we need to maintain a prosperous nation?

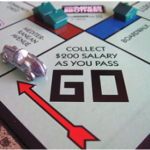

Searching for an answer, I discovered a small (but growing) group of economists (see here, here, here, here, here, here) who represent an emerging school of thought known as “modern monetary theory” (MMT). These men and women are valiantly trying to make us all understand a paradigm shift that occurred some forty years ago, when the world abandoned the gold standard. Their key insight shocked me: A sovereign government is never revenue constrained when it is the Monopoly issuer of its own pure fiat currency; it has all the money that’s needed to put its citizens to work building anything—and providing any service—that is desired by the public (provided the real resources are available). Even more remarkable, sovereign “deficits” in the fiat currency are just the accounting record of the surpluses that have been injected into the private economy. Eliminating the sovereign currency deficit by imposing austerity will not make the economy healthier; it will, in effect, bankrupt the citizens!