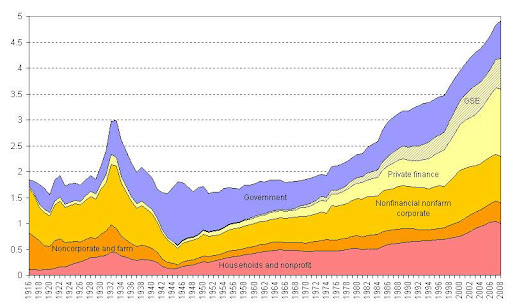

The U.S. now has the highest ratio of debt-to-GDP in its history: nearly 5. And, while much has been made of the public sector’s growing debt levels, private finance has been the leading contributor to this massive growth of indebtedness. Two other contributors are GSEs (private/public financial sector) and households.

Figure 1: Total Financial Liabilities by Sectors Relative to GDP Sources: Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennium Edition, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, NIPA, Flow of Funds (from 1945).

Sources: Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennium Edition, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, NIPA, Flow of Funds (from 1945).

Securitization, together with internationalization of finance, has been the main driver of those tendencies, enabling the financial sector to reap large profits…until recently.

Figure 2: Proportion of Corporate Profit Received by the Financial Sector*

*Excludes Federal Reserve Banks.

Source: BEA. Tables 6.16B, 6.16C, and 6.16D. Corporate profit with inventory valuation and net of capital consumption.

Interestingly, debt levels in the 1980s rivaled those of the Great Depression, which gave a hint that the quality of indebtedness matters as much as the quantity of debt. Take mortgages for example: IO mortgages were a major problem during the Great Depression, which led to a reform of the mortgage industry toward long-term fixed, fully-amortized mortgages. Until the early/mid 2000s, IOs and other exotic mortgages were of limited proportion or non-existent, but as the quality of mortgage deteriorated so did the capacity to sustain a given level of indebtedness.

Solving the debt problem is going to take many years and radical steps (some of them on the distributive and employment sides rather than the financial side). Already financial institutions are cutting the amounts due on credit cards (sometimes in half!) if customers are willing to repay in full at once. Creditors are beginning to understand the enormous problem posed by massive indebtedness. Policymakers should take note: a sustainable economic recovery cannot take place without first allowing private sector balance sheets to recover.