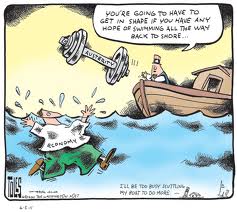

As Stephanie Kelton has recently published two excellent pieces explaining the sector balances in the context of government “belt tightening” (see here and here), a logical next step is to present this in the sector financial balances model of aggregate demand. This post will only briefly review that model before applying it to austerity policies; those desiring more complete background can find it here, and a printable version here. Posts by several others describing various aspects of the model are also linked to therein.

Bank Whistleblowers United

Posts Related to BWU

Recommended Reading

Subscribe

Articles Written By

Categories

Archives

March 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Blogroll

- 3Spoken

- Angry Bear

- Bill Mitchell – billy blog

- Corrente

- Counterpunch: Tells the Facts, Names the Names

- Credit Writedowns

- Dollar Monopoly

- Econbrowser

- Economix

- Felix Salmon

- heteconomist.com

- interfluidity

- It's the People's Money

- Michael Hudson

- Mike Norman Economics

- Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis

- MMT Bulgaria

- MMT In Canada

- Modern Money Mechanics

- Naked Capitalism

- Nouriel Roubini's Global EconoMonitor

- Paul Kedrosky's Infectious Greed

- Paul Krugman

- rete mmt

- The Big Picture

- The Center of the Universe

- The Future of Finance

- Un Cafelito a las Once

- Winterspeak

Resources

Useful Links

- Bureau of Economic Analysis

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- Central Bank Research Hub, BIS

- Economic Indicators Calendar

- FedViews

- Financial Market Indices

- Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In

- FRASER

- How Economic Inequality Harms Societies

- International Post Keynesian Conference

- Izabella Kaminska @ FT Alphaville

- NBER Information on Recessions and Recoveries

- NBER: Economic Indicators and Releases

- Recovery.gov

- The Centre of Full Employment and Equity

- The Congressional Budget Office

- The Global Macro Edge

- USA Spending

-