By Eric Tymoigne

It may surprise you to know that the banking sector is one of the most regulated industries in the United States with a bank having to file regulatory documents with several agencies. These regulations determine how banks should and should not operate their business in terms of many aspects; from disclosure of information to potential customers, to means of determining creditworthiness of a potential client, to the amount of reserves to hold, to management issues, among others. For example the National Association of Mortgage Brokers noted in 2006

Mortgage brokers are governed by a host of federal laws and regulations. For example, mortgage brokers must comply with: the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA), the Truth in Lending Act (TILA), the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA), the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), and the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act), as well as fair lending and fair housing laws. Many of these statutes, coupled with their implementing regulations, provide substantive protection to borrowers who seek mortgage financing. These laws impose disclosure requirements on brokers, define high-cost loans, and contain anti-discrimination provisions. Additionally, mortgage brokers are under the oversight of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC); and to the extent their promulgated laws apply to mortgage brokers, the Federal Reserve Board, the Internal Revenue Service, and the Department of Labor.

Let’s focus on four examples of regulation.

Examples of Bank Regulations

Reserve Requirement Ratios

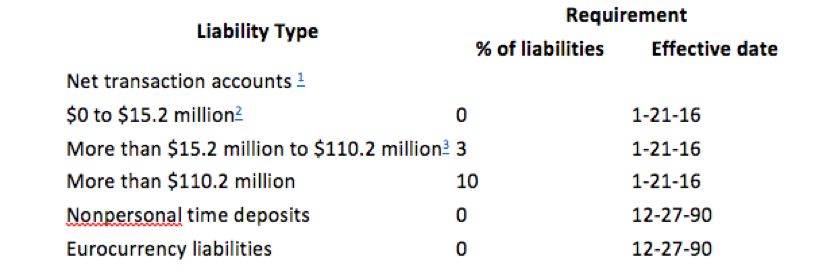

The reserve requirement ratios (RRR) dictates the amount of total reserves banks must have in proportion of the accounts they issued. Table 1 shows what the ratios look like today in the US. If a bank issued less than $15.2 million of transaction accounts (checking accounts and others) it does not have to have any reserves, 3% between 15.2 to $110.2 million worth of outstanding transaction accounts, and 10% beyond that. Some countries do not have any reserve requirements.

Table 1. Reserve Requirement Ratios in the United States

Source: Federal Reserve

Capital Adequacy Ratios

Say that a bank has the following balance sheet: the value of assets is $100, bank accounts are $90 and net worth is $10. The net worth acts has a buffer for account holders against losses on assets, i.e. as long as, the value of assets falls by 10% or less, the bank can fully repay all account holders by liquidating its assets (assuming, of course, that at time of liquidation markets are well behaved and allow quick liquidation at no cost). Regulators want to make sure that banks have enough capital to protect their creditors against a substantial decline in the value of bank assets. This is all the more so that government may guarantee that customers will get the funds in their bank accounts even if a bank goes bankrupt.

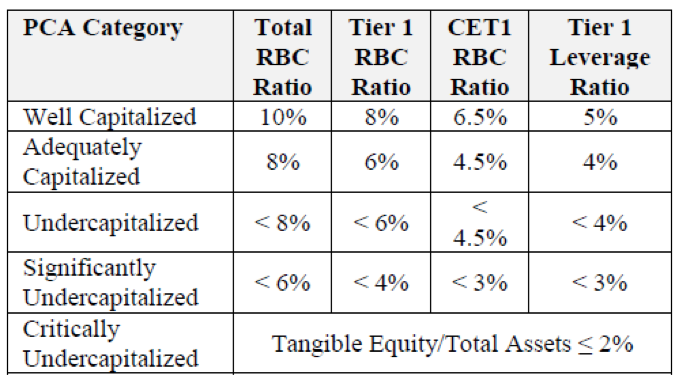

Since 1988 with the Basel Accords, central banks have tried to make capital regulation more uniform across the world. Table 2 shows the current capital adequacy ratios (CAR) for FDIC-insured banks. We will focus on the total risk-based CAR (Total RBC ratio column). In the US, a bank should have at least 8% of capital, preferably at least 10%, relative to its risk-weighted assets. This means that the maximum weighted balance-sheet leverage ought to be 12.5 (A/E = 1/0.08) and preferably 10.

Table 2. Capital Adequacy Ratios.

Source: FDIC Capital Regulation Manual.

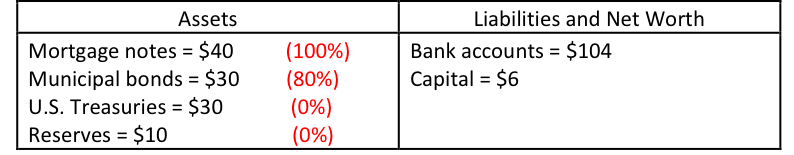

Assets are weighed according to the risk that their nominal value falls. Assume that a bank as the following balance sheet

Figure 1. Bank balance sheet with Weights

The ratio capital/assets is $6/$110 = 5.45%, which is below the 8% minimum CAR. However, assets weigh more heavily if they have a higher chance of generating losses. Mortgage notes are illiquid and contain credit risk so they are attached a 100% weight, municipals contain credit risk but are somewhat liquid so they have a weight of 80%, U.S. treasuries contain no credit risk and trade in the most liquid financial market in the world so they are attached no weight. Same with reserves. So the actual capital ratio is $6/($40 + $24) = 9.38%, not ideal but adequate.

Basel Accords have evolved overtime as central banks have tried to account for changes in the financial industry and for drawbacks of the previous versions of the Accords (the Accords are in their third version). As one may expect, the way to set the weights and proper value of assets can get very complicated. The last section will explain why one may doubt that this type of regulation will be successful.

CAMELS rating

Beside the well-known RRR and CAR, regulators such as the FDIC also calculate a CAMELS rating for each bank:

- C: Capital adequacy

- A: Asset quality

- M: Management quality

- E: Earnings level and quality

- L: Liquidity

- S: Sensitivity to market risk (change in the nominal value of securities)

CAMELS rating goes from 1 (strong business) to 5 (highly troubled). A rating of 4 or higher leads regulators to check carefully a bank and if necessary to issue a cease and desist order

In a cease and desist order, a bank must stop immediately its dangerous activities (risky credit, improper management, too low capital ratio, etc.) and must find means restore its soundness permanently (as measured by the CAMELS rating). Restoring permanent soundness (i.e., desisting from dangerous activities) may imply significant changes in management and business strategy, finding reliable sources of funding, and other relevant restructuring operations. The board of a troubled bank is given a limited amount of time (e.g., 60 days) to comply with the demands of its regulator. If the board cannot comply, the bank is closed and the regulator uses the least costly procedure to take care of the problem bank: liquidation or facilitation of acquisition by another bank.

Underwriting Requirements

One would think that banks carefully check the creditworthiness of a customer before they accept her promissory note. They would ask for proof of income and verify with the Internal Revenue Services (nobody inflates his income on an income-tax statement), carefully determine the value of available collateral, and judge ability to pay based on the overall debt service that would come due. After all, this is what banks are supposed to do; their job is precisely to judge ability to pay and to tame expectations.

As noted in Post 8, during the housing boom all this went out of the window, banks manufactured creditworthiness by inflating it on credit application (sometimes raising the income stated on a mortgage application without the knowledge of the applicant), they did not bother to check with the IRS even though it can be done easily (they did not do so for the obvious reason that they lied on the application), they maintained a black list of house appraisers who were honest and would not provide an inflated valuation of a house, they qualify households on the basis interest payments calculated from a very low interest rate (aka teaser rate) that would prevail only for a few months. It is as if your mechanics did everything to wreck the engine of your car. So it turned out regulations had to be put in place regulations to tell bankers what they are supposed to do!

This is included in Title 14 of the Dodd-Frank act. It forces mortgagees to determine the capacity to pay of mortgagors on the basis of other means than the expected refinancing sources and expected equity in the house, as well as to verify income and to qualify individuals based on the full debt service:

A determination under this subsection of a consumer’s ability to repay a residential mortgage loan shall include consideration of the consumer’s credit history, current income, expected income the consumer is reasonably assured of receiving, current obligations, debt-to-income ratio or the residual income the consumer will have after paying non-mortgage debt and mortgage-related obligations, employment status, and other financial resources other than the consumer’s equity in the dwelling or real property that secures repayment of the loan. A creditor shall determine the ability of the consumer to repay using a payment schedule that fully amortizes the loan over the term of the loan. (Dodd-Frank Act, 768)

While Title 14 is limited to residential mortgages (commercial mortgages were a big problem during the S&L crisis and other promissory notes should also follow the same underwriting methods), this Title is a great contribution to financial stability…if enforced. The need for such a regulation suggests how much the banking industry has changed for the worst.

Why are there still frequent and significant financial crises if regulation is so tight?

This is, at least, a three-part answer: 1- there was some deregulation that has promoted competition and concentration, 2- the willingness and ability to enforce the law has diminished, 3- regulatory arbitrage and regulatory apathy.

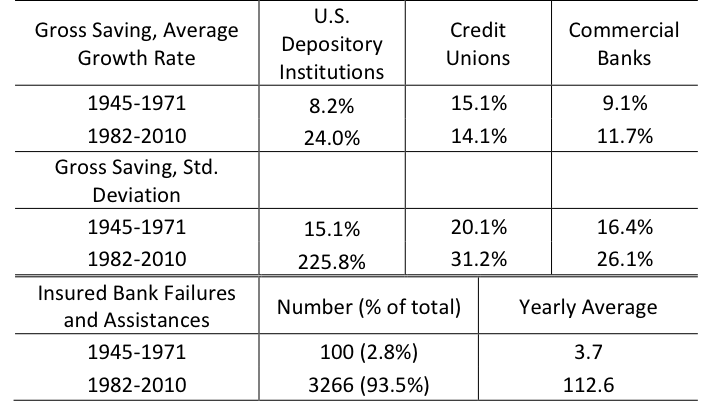

The Great Depression put in place financial regulations that compartmentalized the financial industry. Banks were forbidden to perform some activities related to financial markets, they were limited in the types of assets they could hold, and they had access to a low cost and stable refinancing source via the central bank. This led to a very stable banking system with very few limited problems. Table 3 shows the gross saving of depository institutions grew at a slower but steadier pace. The number of failures and assistances was also dramatically smaller—around 4 failures and assistances per year versus 113 from the 1980s—and represented only 2.8 percent of all failures and assistances that occurred between 1945 and 2010. Taking a broader historical perspective. Figure 2 shows that the stability of the banking from 1940 to 1980 also stands out.

Table 3. Gross Saving and Failures of Depository Institutions.

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Note: Gross saving is defined as undistributed profit plus consumption of fixed capital

Figure 2. Annual Number of Bank Suspensions (1892-1941) and Bank Failures (1934-2015)

Source: FDIC (Bank Failures) and Monetary and Banking Statistics 1914-1941 (Bank Suspensions)

Note: Bank suspension includes banks that closed temporarily or permanently on account of financial difficulty; excludes times of special bank holiday. Bank failures refer to banks that were permanently closed.

Post 8 notes that the enthusiasm of banks for the originate-and-hold model declined sharply in the 1980s. They pushed for a deregulation of their industry to be able to offer higher interest rate on their liabilities and to widen the type of assets they could hold (1980 Depository Institution Deregulation and Monetary Control Act, 1982 Garn St. Germain Act). Then, banks lobbied to deregulate branching restrictions (1994 Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act), to be able to participate in broader financial activities (1999 Financial Modernization Act), and to limit regulation in the derivative markets (2000 Commodity Futures Modernization Act).

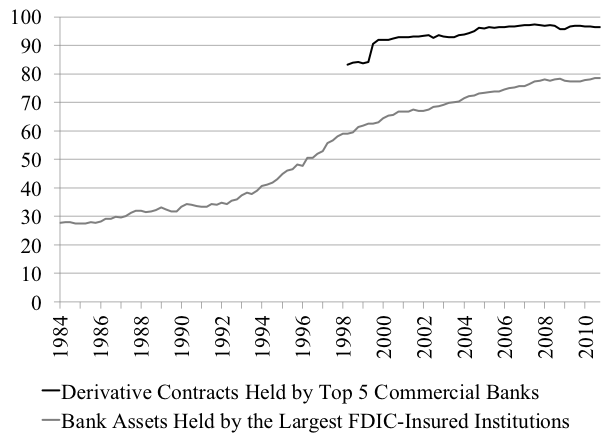

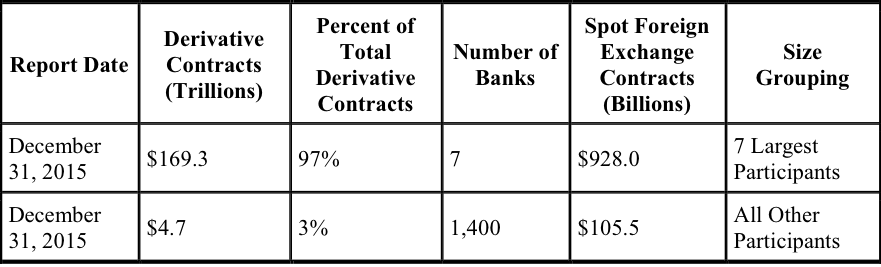

Today, the U.S. banking industry is highly concentrated (Figure 3) and a few large financial holding companies dominate the industry. 80% of the assets of the banking industry are concentrated in the 595 largest banks that account for about 10% of FDIC-insured banks. Among these, the top 5/7 banks hold almost all the derivative contracts held by banks. Table 4 shows the recent data about derivative holding concentration among FDIC-insured institutions; the seven biggest institutions hold 97% of derivate contracts held by FDIC-insured institutions, worth almost $170 trillion notionally.

Figure 3. Concentration of the banking industry

Note: Largest FDIC Insured Bank have over $10 Billion of Assets (595 institutions in 2016 or 10% of the industry)

Table 4. Concentration of Derivatives Notional Amounts

Source: FDIC Graph Book

Overall, there was a deregulatory trend but the fact remains that this industry is still heavily regulated. However, for a set of regulations to work properly it has to be enforced. With the return of free-market thinking as a dominant framework of thought in the 1970s, enforcement took a toll. Free-market thinkers who do not believe in government intervention were put in charge of major regulatory bodies. Individuals such as Greenspan at the Fed, Rubin at the Treasury, Cox at the SEC. Individuals who believe in the self-cleansing and self-stabilizing properties of market. As such, there is no need to do anything to prevent fraud and dangerous financial practices, or to make sure that banks do not get involved in predatory business practices. Markets take care of it, after all, as the thought goes, a business is judged by its clients so if the clients do not like what a business does, the business will close.

Thus, in recent years, regulators like the Federal Reserve deliberately loosely implemented existing regulations or chose “to not conduct consumer compliance examinations of, nor to investigate consumer complaints regarding, nonbank subsidiaries of bank holding companies” (Appelbaum 2009). In addition, the Federal Reserve and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) blocked efforts of federal regulators, and states like Georgia and North Carolina were prohibited by OCC and the OTS from investigating local subsidiaries of national chartered banks. Chairman Bair at the FDIC worked with Federal Reserve Governor Gramlich to raise concerns about predatory mortgage practices from 2001 but their effort did not lead anywhere. Chairman Born at the Commodity Futures and Trade Commission (CFTC) raised concerned about derivatives and wanted to make them more transparent but was shut down by Congress.

In 1994, a Government Accountability Office (GAO) strongly criticized the existing derivatives legislation. It noted that “no comprehensive industry or federal regulatory requirements existed to ensure that U.S. OTC derivatives dealers followed good risk-management practices” and that “regulatory gaps and weaknesses that presently exist must be addressed, especially considering the rapid growth in derivatives activity” (Government Accountability Office 1994: 7-8). None of the recommendations was implemented and instead large cuts were made by Congress to the budget of the GAO. These cuts were estimated to reduce the staff of the GAO by 850 persons (20 percent of its employees).

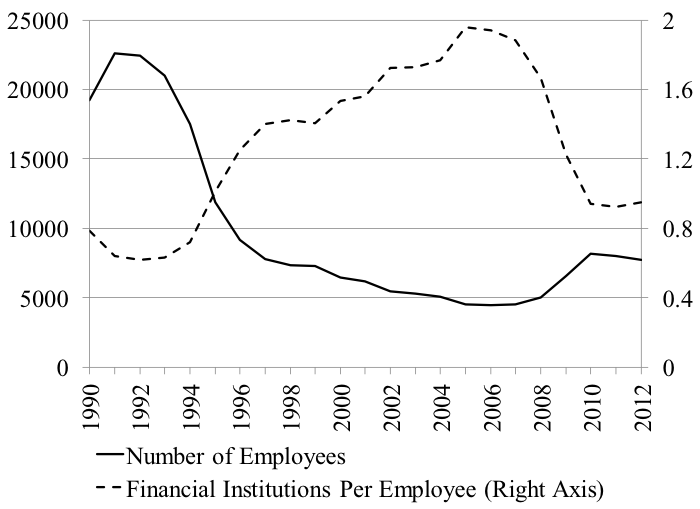

Other regulators also suffered large cut in their staff. The FDIC staff was cut drastically and constantly from 20,000 employees in the early 1990s to 5,000 employees right before the Great Recession (Figure 4). This occurred at the same time as the financial industry became more concentrated and more complex. In addition, the cut in staff was much more rapid than the decline in the number of FDIC insured institutions to be supervised, thereby increasing the burden of supervision on each employee. This double trend of increasing complexity and increasing burden on supervisors drastically decreased the capacity to perform effective supervision and regulations.

The SEC, under Christopher Cox (who, like Alan Greenspan, is a follower of Ayn Rand’s economic thinking) also decreased its staff and, by 2009, the Securities and Exchange Commission had 400 people to examine 11000 investment advisers, which led it to contract with private auditors and other external reviewers. In addition, the SEC did not develop the necessary tools it needed to perform effective regulation.

Beyond deregulation and deenforcement, banks themselves have always found means to bypass partly some of the regulations that they have found too constraining. An example of that are capital regulations that banks have bypassed partly through securitization. Securitization allows banks to remove highly-weighted assets from their balance sheet without compromising their profitability. Regulatory arbitrage is a common response of banks to new regulations. To counter it, regulation needs to be flexible and broad enough and regulators need to act quickly; both requirements are lacking with regulators today focused on limiting intervention to avoid hurting bank profit and competitiveness with foreign institutions. In addition, a bank can choose its main regulator, and a bank can switch if it thinks another regulator will be more lenient. This “regulator shopping” is all the more prevalent that regulators compete to get the most banks under their wings because regulators are funded partly through the fees they charge for supervision.

Figure 4. Number of Employees at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

Source: FDIC.

Theories of bank crises and banking regulation: Two views

The way the banking system is regulated heavily depends on regulators’ understanding of what causes banking crises. There are two broad views regarding the origins of banking crises and financial crises more generally; one states that crises are random events in an otherwise self-stabilizing economic system based on market principles, another states that bank crises are the result of the inner working of markets.

Greenspan summed up neatly the first view when he characterized the 2008 financial crisis as a “once-in-a-century credit tsunami.” Crises are equivalent to weather calamities that affect the return on assets. These adverse random shocks are amplified by individual imperfections (think of any deviation from the cold rational homoeconomicus) and market imperfections (lack of information, etc.). Market imperfections can themselves contribute to the growing risk of financial crises if they contribute to the mispricing of securities, which leads rational agents to take too much risk on their assets and liabilities given the price signal. Thus, according to this view, the recent crisis is the product of mispriced assets (like CDOs) that led to the issuance of too many of them (see discussion about embedded leverage in Post 7), and of a “black-swan” event, that is, an unusually large negative shock. One might call this view the “shit-happens” view of financial crises.

In this type of view, there is no point in trying to promote a regulatory framework that proactively helps prevent crises and limit their strength—in the same way no one can proactively prevent the occurrence and strength of tsunamis. Market mechanisms weed out problems by themselves because, with enough disclosure, financial-market participants will not engage in fraudulent practices and unsustainable business will be closed down. Anything that promotes market mechanisms is praised and that includes the recent innovations in derivatives and securitization. Policy makers such as Alan Greenspan and academics such as Philip Das made statements in the mid 2000 that illustrate well this position:

Development of financial products, such as asset-backed securities, collateral loan obligations, and credit default swaps, that facilitate the dispersion of risk… These increasingly complex financial instruments have contributed to the development of a far more flexible, efficient, and hence resilient financial system than the one that existed just a quarter-century ago. (Greenspan 2004, 2005)

Financial risks, particularly credit risks, are no longer borne by banks. They are increasingly moved off balance sheets. Assets are converted into tradable securities, which in turn eliminates credit risks. (Das 2006)

Given that markets usually get it right, instead of having regulations that constrain market mechanisms, regulation should focus on limiting the destructive impact of financial crises on economic activity and improving disclosure of information and market mechanisms. Following the tsunami analogy, the goal is to build high enough seawalls so that protection is available against most tsunamis. If there is a “once-in-a-century” tsunami…well…too bad…at least we tried!

In terms of banking regulation, the goal is to put in place large enough liquidity and capital buffers in the balance sheets of banks. The Basel accords are an example of such regulatory view:

Given the scope and speed with which the recent and previous crises have been transmitted around the globe as well as the unpredictable nature of future crises, it is critical that all countries raise the resilience of their banking sectors to both internal and external shocks. (Basel 2010a: 2)

With enough capital, banks will be able to protect their creditors against most declines in the value of their assets. With enough liquid assets, the value of assets will decline less than it would have otherwise. At the same time, having too much capital and liquidity puts downward pressures on the ROE that banks can earn because leverage declines and ROA is lowered (the more liquid an asset, the lower the ROA). The point, therefore, becomes to find the optimal level of capital and liquidity. The move toward risk management is the ultimate expression of this belief. It uses complex mathematical algorithms to determine what the appropriate level of buffers is given existing risks on- and off-balance sheets. The goal has been to refine the measurement of different risks as well as the methods used to calculate the appropriate level of each buffer. The government has a limited role to play in determining appropriate buffers, especially for “sophisticated” financial institutions. The government also has not much to say about the way banks should be managed, the proper underwriting procedures, and the types of assets that banks should be allow to hold. Bankers know best.

Another view of financial crises argues that they are the normal result of profit-seeking operations of banks, and that the way the banking system is structured greatly dampens or amplifies the destabilizing effect of profit-seeking operations. While an unstable banking system can be attributed in part to greed and irrational or “bad” people, the most important contributor is the way the banking system is set up. The more role is given to market mechanisms, the more unstable the financial system will be. The issue is not one of mispricing, lack of disclosure, black swan, massive tsunami, or imperfections. Tsunamis are created by the very practices of banks when trying to make a buck and, if banks are left alone, their practices will lead to a “once-in-a-century tsunami.” Put differently financial crises are not the results of “bad luck” because nature threw a tantrum; banks make their own luck. As such, one may also doubt that capital regulation and other buffer-requirement approach will do much to prevent financial crises. They are too passive regulations.

As explained in Post 8, over a period of stability, banks are incentivized to change their underwriting practices by lowering credit standards and/or deemphasizing income as the main means of servicing debts. Some of this loosening is welcomed when banks have tightened credit standards so much that economic growth cannot proceed well. This will tend to happen after financial crises, when bankers become too careful (remember when Chairman Bernanke could not refinance his mortgage). However, credit standards are elastic and, when profitability is threatened, loosening credit standards is the easy road especially during a period of economic stability when economic news is good. Periods of economic stability feed the models used by bankers with information that suggests that leverage is safe and risk-taking is warranted.

Beyond banks, other financial institutions such as pension funds have an incentive to buy CDOs and other risky assets (even with non-investment grade) in order to maintain the targeted ROE they promised to their pensioners; this is so especially when interest rates are very low. More broadly, corporate businesses have some profitability target to meet that is largely invariant to the growth of their assets, thereby pushing them to innovate and to use leverage to reach that target. Again, a very rational response to profitability pressures defined by a target ROE.

As such, risk-management tools may provide information that suggests that it is safer not to engage in certain activities, but this information will be ignore if it threatens market shares and profitability:

To some extent […] all risk management tools are unable to model/present the most severe forms of financial shocks in a fashion that is credible to senior management […].To the extent that users of stress tests consider these assumptions to be unrealistic, too onerous, […] incorporating unlikely correlations or having similar issues which detract from their credibility, the stress tests can be dismissed by the target audience and its informational content thereby lost. (Counterparty Risk Management Policy Group III 2008: 70, 84)

This is so especially in an environment where it is difficult to reach the target ROE and the search for yield is intensive. Post 8 illustrates how the banking system (and financial system as a whole) is driven by competitive pressures and the need to stick with the majority to avoid losing market shares. As such, financial institutions will engage in unsustainable financial practices if that means keeping profitability up. Given that profit is the only relevant metrics to judge a business, market mechanisms will not weed out unsustainable practices if they sustain profit. As these accumulate, the economic system becomes more fragile and ultimately collapses under a debt-deflation (see Post 14).

The point is that the weeding out of bad apples that market proponents argues occur to prevent crises does not happen. The problem comes from too much focus on profit as the key metrics of health for a business. From the banker managers’ standpoint if the business is profitable, it means they do what customers want and so are fulfilling a need (nevermind that this may involve “raping the public”). Regulators see profit as a key measure of health because profit grows capital and so improves buffers against crises. However, from a financial stability perspective, a key issue is not merely if profit is generated but how that profit is generated. If this second question is ignored, the weeding out mechanism used by markets is the crisis itself, and that ends up destroying the entire economy and wiping out any buffer available. So much for a smooth self-stabilizing mechanism.

Given that credit standards are elastic concepts, one may wonder if there is a means to know what a sustainable credit practice is and how to use that for regulatory purpose. Fortunately yes. Hyman P. Minsky provides us with a useful categorization of underwriting practices in terms of Hedge, Speculative and Ponzi finance. Post 14 studies this categorization more carefully. Their main point is that if debt is underwritten on the basis of income (income-based credit), it is much less likely to lead to financial instability. If, instead, banks grant advances by qualifying clients on the basis of the expected rise in the value of a collateral or other assets (asset-based credit), then the economic system is prone to financial instability. The recent housing boom with its dangerous mortgage practices, presented in Post 8, is an example such unsustainable underwriting practices.

The problem is not merely of knowing if a customer will be able to service his debt (the main concern of banks), but also HOW he will service his debt: servicing debt with income is sustainable, servicing debt by liquidating assets is not. It is not sustainable because while an individual may be able to do it by relying on a bonanza (asset prices went up as expected and can be liquidated easily), for the system as a whole it is impossible to liquidate assets. Markets rely on a balance of buyers and sellers and if a significant proportion of debtors rely on a strategy that involves selling assets to service debts, asset prices will plunge when liquidation occurs. A Ponzi strategy is only sustainable for so long given that the number of participants (and indebtedness) must exponentially grow to keep the strategy going.

With the H/S/P categorization in mind, the point is to discourage, and if necessary, forbid any economic growth process that is not based on sound financial practices (income-based credit), even if everybody is profiting from the continuation of this process in the short term, and even if the financial community ends up considering those practices acceptable and a normal way to do business. In order to do so, the financial practices of economic agents should be checked carefully and growing signs of asset-based credit should be tackled immediately, even if there is no bubble, no rising default rate, rising wealth and profit.

This policy agenda is, of course, much broader and more ambitious than the previous one, but its relevance has been demonstrated many times. For example, prior to the savings and loan crisis, several in-field supervisors wanted to shut down some thrifts that were recording large profits, because they were suspected to be involved in Ponzi finance sustained by massive frauds. However, there were strong pressures from their bosses and politicians not to close these thrifts because their profitability made them models for the industry (Black, 2005). Those thrifts were allowed to continue to operate but ended up costing hundreds of billions of dollars when they failed.

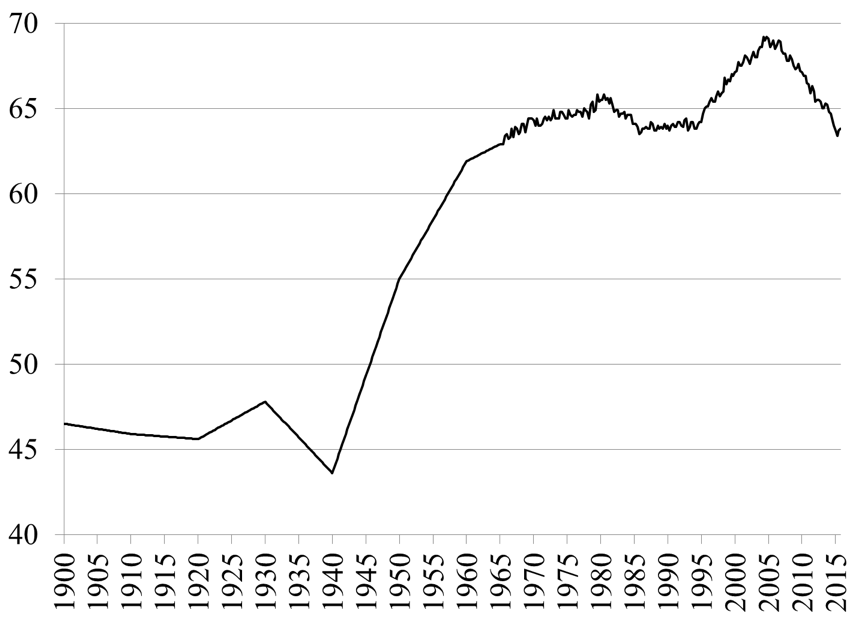

Similarly, during the housing boom of the mid-2000s, households’ wealth grew very rapidly, financial companies registered record-high profits, and homeownership also reached a record high, but all these gains were wiped out once the economy collapsed. Homeownership is back to its level prior to the housing boom, and is still falling (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Homeownership Rate in the U.S. (Percent).

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Steps should have been taken since at least 2003 to prevent the unsustainable growth of homeownership and dangerous business practices. This should have been done by forbidding no-doc mortgages, by limiting access to pay-option mortgages to households with enough cash buffer and income, by not allowing financial institutions to create Ponzi-generating financial innovations, and by regulating closely all new financial activities. Instead, Greenspan praised the dynamic mortgage market and argued that rising mortgage debt among U.S. households was not a problem because households’ wealth was rising thanks to rapidly rising home prices (Greenspan 2004); precisely what asset-based credit is all about.

Finally, asset-based credit is impossible to buffer properly in an economically profitable way and so should not be allowed at least by banks. An alternative is to remove any government backing from economic activities that rely on, or promote, asset-based credit, which implies isolating the payment system from those activities.

In the end, CDOs and other financial innovations were problematic not because they were mispriced (although they surely were), but because they were encouraging financial practices that are unsustainable even if priced correctly. Asset-based credit always fails because there is ultimately no income to meet the debt service and assets must be liquidated in distress. Financial-market participants are always willing to pay for something if that means more profit (even more so when bonuses are based on short-term profitability), and they will get a better idea of what to pay with more information. But profit-seeking activity is different from financial-crisis avoidance activity. In fact, these two activities usually are complete opposite activities and the latter is never on the radar of any particular firm (“if we fail, we fail together, nobody gets blamed; let me focus on my profit” is the thought as Wojnilower illustrates).

That is it for Today! Next post examines how banks create and destroy monetary instruments and surrounding issues, and in the process the post will study more carefully the balance-sheet mechanics of banks.

[Revised 8/6/2016]

8 responses to “Money and Banking – Part 9: Banking regulation”