In addition to the House Budget Committee and OMB budget plans and 2016 – 2025 projections fiscal policy followers have also recently been graced with the effort of the Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) proposing their budget plan and 2016 – 2025 projections. The CPC budget proposal is interesting because it is definitely not intended to be an austerity budget. Instead, its authors consciously try both to achieve the goals of “fiscally responsible” low deficit budgets while turning away from austerity and towards achieving full employment, renewed economic growth, economic stability, a strengthened social safety net, greater economic equality, an improved infrastructure, and transportation system, improving the health insurance system beyond the Affordable Care Act, a greener economy, improved education and other progressive goals.

The CPC proposes to do that in two ways First, by raising Federal revenues from 17.5% of GDP in 2014 and 2015 to 20.2% of GDP in 2016, and then more gradually to 21.5% in 2025, while raising Federal outlays from 20.3% of GDP in 2014 to 22.6% in 2015, and 23.7% in 2016, then stays in the range from 22.3% to 23.1% for the rest of the period. Since they also assume GDP growth rates in the neighborhood of 4.1% of GDP to 4.5% year after year over the period, these assumptions imply freed up funds the caucus believes are necessary to support its programmatic changes.

And second, the CPC budget also tries its best to maximize the fiscal multipliers of its various programs, while minimizing the negative fiscal multipliers of its tax programs for raising revenue as a percent of GDP. Since low levels of deficit spending are adhered to in the CPC budget, the fiscal impact of its government outlays is lessened greatly by the negative effect of the rising tax revenues.

According to an analysis of the CPC budget by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), “A fiscal multiplier of 1.4 has been assigned to government spending provisions, and a fiscal multiplier of 0.5 has been assigned to tax provisions.” (p. 24) The EPI report also says (p. 10):

Although tax increases are contractionary in current conditions, the economic impact of a dollar of government spending (as shown by the fiscal multiplier) is about four to seven times higher than the economic impact of a dollar of revenue (Bivens and Fieldhouse 2012). Since much of the revenue would be raised from upper-income households and businesses (which have relatively low marginal propensities to consume and thus particularly low fiscal multipliers even among tax changes) and used to finance high bang-per-buck job creation measures, the relatively small fiscal drag from raising revenue would be more than mitigated by the other budget policies.

The Bivens and Fieldhouse report dealing, partly, with fiscal multipliers is here.

The CPC is correct to claim that its budget will improve the economy more than budgets offered by other parties that receive coverage in the current fiscal debates. Nevertheless, I think the reorientation of US fiscal posture over the next decade is still somewhat underwhelming. For example, CPC’s collaborators at EPI claim:

The budget’s near-term economic stimulus measures would create 4.7 million jobs in calendar year 2015 and an additional 3.8 million jobs over the following two years. By the end of calendar year 2018 the People’s Budget would support 9.1 million job years and would ensure a prompt and durable return to full employment.

But, 9.1 million jobs created by the end of 2018 would still leave more than 11 million people who want full time jobs still without them, by CPC’s own admission found on p. 3 of its “People’s Budget” linked to above. And this estimate doesn’t take into account additions to the labor force wanting full time jobs over the next four years. So much for the CPC budget approaching full employment by 2018 or any time during the next decade.

CPC also says that its budget will make a down payment of $820 Billion additional spending to help close the infrastructure gap. No doubt this will help the present terrible situation. But its claim that the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) says that upwards of $One Trillion is needed to fix our infrastructure is a little misleading because it suggests that their “down payment” is some where near adequate to solve the problem. However, the ASCE estimates that $3.6 Trillion should be spent by 2020, which means that more than $4 Trillion should be spent between now and 2025.

So, the truth is that the CPC budget allocation for infrastructure is terribly inadequate, even though it is much greater than in competing budgets. This is one of the effects of trying to provide a progressive change program, while accepting the underlying assumption that deficits must be reduced to reach a “sustainable” level of the national debt.

There are number of other areas where the CPC budget tries to make substantial improvements over other budgets, but still does not solve problems. One of these is in the health insurance area, where it proposes improving the Affordable Care Act by repealing the excise tax on high end health insurance plans and replacing that tax with a public option. It also proposes making it easier for States to elect to move to single-payer health insurance if they want to. However, it stops short of incorporating enhanced Medicare for All in its budget even though it would save the American people perhaps $900 Billion in Medical costs per year. What’s happened to John Conyers, Jr. I wonder?

Why? Probably because the increase in Government spending required by Medicare for All would imply either higher revenues or more deficit spending, or a combination of both to implement, and the CPC didn’t want to move outside the deficit reduction/”fiscal responsibility” neoliberal framework to advance that proposal. Other areas in which that sort of motivation is apparent is in increasing Social Security benefits, which CPC supported, but wanted to handle outside of the budget process, and in education where CPC was for free college going forward and lowering interest rates on past student loans, but for student loan forgiveness.

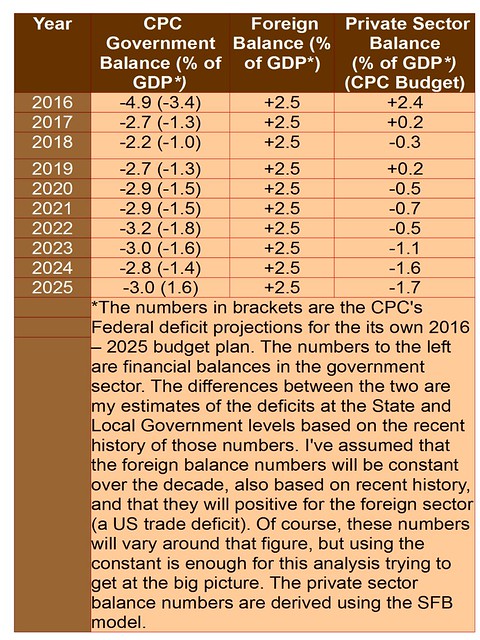

There are other grounds on which progressives might criticize the CPC than mentioned so far, but the most important criticism of its suggestions is in its failure to incorporate the impact of sectoral financial balances in its projections. In previous posts, on the proposed House and OMB budgets, I’ve offered a short summary on sectoral financial balances and suggested why they’re important to take into account. I’ve included that summary in an appendix to this post for the convenience of readers. But now let’s turn to the likely implications of the CPC Federal budget deficit projections from 2016 – 2025, for the sectoral financial balances in Table One.

Table One: Sector Financial Balance Projections (from CPC) 2016 – 2025

The significance of years of these private sector deficits, or very small deficits, is that they are likely to hurt private sector balance sheets badly, especially those of middle class and poor people, cutting into aggregate demand and the credit worthiness of large swathes of the population. Eventually that will lead to a pull back of credit in the private sector, followed by declining sales, increased unemployment, and expansion of safety net expenses.

The CPC budget relies on its fiscal multipliers to kick up growth and employment in 2015 and 2016, but after those years of deficit spending offsetting demand leakage from the current account deficit, there is nothing in the CPC budget to continue to offset the demand leakage at the new higher level of GDP, or to satisfy the savings, or increased consumption desires of the private sector. So, we will have a private sector consistently losing net financial assets. Such losses, due to structural factors of economic influence and power, will be unequally distributed and be borne more by the middle class and the poor, rather than the 1%. This means a consumption downturn and a spiraling of the economy downward.

When that recession happens, the CPC budget will already have a stronger safety net and jobs programs in place to handle it, and that is all to the good, but it also means that even if the CPC budget were passed and were successful in growing the economy for a few years, its drive toward small deficits will cause a pullback, and then its automatic stabilizers will drive up government deficits invalidating its deficit projections, which are, frankly, unbelievable in the absence of a credit bubble to sustain demand. These deficits won’t be as bad for people as a downturn in the presence of a budget plan that has weakened or removed the automatic stabilizers, but it still will mean an economic pullback causing widespread and growing unemployment once again, and a further need to “fix” the economy.

The macroeconomic constraints on budget planning implied by the sectoral balances suggest that if we want to stabilize our economy in a sustainable way, we have to create budget plans that will accommodate private sector desires to both run trade deficits and have a reasonably sized private sector surplus every year. Assuming that 6% of GDP is reasonable for that surplus and that the private sector would like to import 2.5 – 3.0% of GDP more than it exports, that means that a fiscally responsible budget for the United States, with the right fiscal multipliers, should approximate an annual government deficit of 8.5 – 9.0% in the US’s present situation.

That’s not something we ought to force with fiscal targets, because the best policy is to let the government deficit float and spend on the right programs to produce full employment at a living wage as well as to implement various programs that will solve our many other problems. However, a level of 8.5 – 9.0 percent of GDP is still a rough measure of how far short of what’s needed even the CPC budget is.

Sector Financial Balances Appendix

The Sector Financial Balances (SFB) model is an accounting identity, and these are always true by definition alone. The SFB model says:

Domestic Private Balance + Domestic Government Balance + Foreign Balance = 0.

The terms refer to balances of flows of financial assets among the three sectors of the economy in any specified period of time. Why must there be flows? Because the three sectors trade financial assets with one another. So, the equation says that the sum of all the balances of flows for the three sectors of the economy is zero, because, since there’s only so much in assets traded in any time period, the positive balance(s) of one or more sectors relative to the others must be matched by the negative balance(s) of the other two sectors.

So, for example, when the annual domestic private sector balance is positive, more financial assets are flowing to that sector, taken as a whole, than it is sending to the other two sectors.

Similarly, when the annual foreign sector balance is positive, more financial assets are being sent to that sector than it is sending to the other two sectors.

And when the annual government sector balance is positive, then it is getting more in financial assets from the other two sectors combined than it is sending to them.

Conversely, when the private sector balance is negative, the private sector is sending more to the other two sectors than it is getting from them, and so on for each of the other two sectors.

Pingback: When Will the Senate Budget Committee Majority Ever Learn About Sector Financial Balances? - New Economic PerspectivesNew Economic Perspectives