(cross-posted with CounterPunch)

The Greek bailout provides an opportunity for privatization grabs

When Greece exchanged its drachma for the euro in 2000, most voters were all for joining the Eurozone. The hope was that it would ensure stability, and that this would promote rising wages and living standards. Few saw that the stumbling point was tax policy. Greece was excluded from the eurozone the previous year as a result of failing to meet the 1992 Maastricht criteria for EU membership, limiting budget deficits to 3 percent of GDP, and government debt to 60 percent.

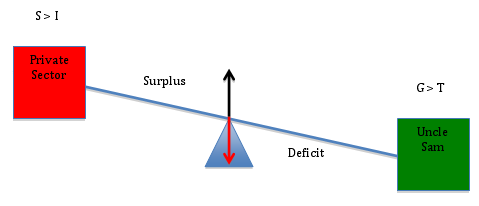

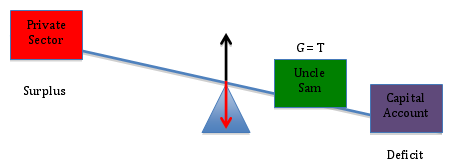

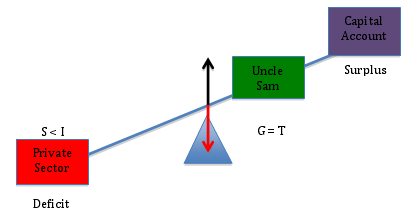

The euro also had other serious fiscal and monetary problems at the outset. There is little thought of wealthier EU economies helping bring less productive ones up to par, e.g. as the United States does with its depressed areas (as in the rescue of the auto industry in 2010) or when the federal government does declares a state of emergency for floods, tornados or other disruptions. As with the United States and indeed nearly all countries, EU “aid” is largely self-serving – a combination of export promotion and bailouts for debtor economies to pay banks in Europe’s main creditor nations: Germany, France and the Netherlands. The EU charter banned the European Central Bank (ECB) from financing government deficits, and prevents (indeed, “saves”) members from having to pay for the “fiscal irresponsibility” of countries running budget deficits. This “hard” tax policy was the price that lower-income countries had to sign onto when they joined the European Union.

Also unlike the United States (or almost any nation), Europe’s parliament was merely ceremonial. It had no power to set and administer EU-wide taxes. Politically, the continent remains a loose federation. Every member is expected to pay its own way. The central bank does not monetize deficits, and there is minimal federal sharing with member states. Public spending deficits – even for capital investment in infrastructure – must be financed by running into debt, at rising interest rates as countries running deficits become more risky.

This means that spending on transportation, power and other basic infrastructure that was publicly financed in North America and the leading European economies (providing services at subsidized rates) must be privatized. Prices for these services must be set high enough to cover interest and other financing charges, high salaries and bonuses, and be run for profit – indeed, for rent extraction as public regulatory authority is disabled.

This makes countries going this route less competitive. It also means they will run into debt to Germany, France and the Netherlands, causing the financial strains that now are leading to showdowns with democratically elected governments. At issue is whether Europe should succumb to centralized planning – on the right wing of the political spectrum, under the banner of “free markets” defined as economies free from public price regulation and oversight, free from consumer protection, and free from taxes on the rich.

The crisis for Greece – as for Iceland, Ireland and debt-plagued economies capped by the United States – is occurring as bank lobbyists demand that “taxpayers” pay for the bailouts of bad speculations and government debts stemming largely from tax cuts for the rich and for real estate, shifting the fiscal burden as well as the debt burden onto labor and industry. The financial sector’s growing power to achieve this tax favoritism is crippling economies, driving them further into reliance on yet more debt financing to remain solvent. Aid is conditional upon recipient countries reducing their wage levels (“internal devaluation”) and selling off public enterprises.

The tunnel vision that guides these policies is self-reinforcing. Europe, America and Japan draw their economic managers from the ranks of professionals sliding back and forth between the banks and finance ministries – what the Japanese call “descent from heaven” to the private sector where worldly rewards are greatest. It is not merely delayed payment for past service. Their government experience and contacts helps them influence the remaining public bureaucracy and lobby their equally opportunistic replacements to promote pro-financial fiscal and monetary policies – that is, to handcuff government and deter regulation and taxation of the financial sector and its real estate and monopoly clients, and to use the government’s taxing and money-creating power to provide bailouts when the inevitable financial collapse occurs as the economy shrinks below break-even levels into negative equity territory.

Regressive tax policies – shifting taxes off the rich and off property onto labor – cause budget deficits financed by public debt. When bondholders pull the plug, the resulting debt pressure forces governments to pay off debts by selling land and other public assets to private buyers (unless governments repudiate the debt or recover by restoring progressive taxation). Most such sales are done on credit. This benefits the banks by creating a loan market for the buyouts. Meanwhile, interest absorbs the earnings, depriving the government of tax revenue it formerly could have received as user fees. The tax gift to financiers is based on the bad policy of treating debt financing as a necessary cost of doing business, not as a policy choice – one that indeed is induced by the tax distortion of making interest payments tax-deductible.

Buyers borrow credit to appropriate “the commons” in the same way they bid for commercial real estate. The winner is whoever raises the largest buyout loan – by pledging the most revenue to pay the bank as interest. So the financial sector ends up with the revenue hitherto paid to governments as taxes or user fees. This is euphemized as a free market.

Promoting the financial sector at the economy’s expense

The resulting debt leveraging is not a solvable problem. It is a quandary from which economies can escape only by focusing on production and consumption rather than merely subsidizing the financial system to enable players to make money from money by inflating asset prices on free electronic keyboard credit. Austerity causes unemployment, which lowers wages and prevents labor from sharing in the surplus. It enables companies to force their employees to work overtime and harder in order to get or keep a job, but does not really raise productivity and living standards in the way envisioned a century ago. Increasing housing prices on credit – requiring larger debts for access to home ownership – is not real prosperity.

To contrast the “real” economy from the financial sector requires distinctions to be drawn between productive and unproductive credit and investment. One needs the concept of economic rent as an institutional and political return to privilege without a corresponding cost of production. Classical political economy was all about distinguishes earned from unearned income, cost-value from market price. But pro-financial lobbyists deny that any income or rentier wealth is unearned or parasitic. The national income and product accounts (NIPA) do not draw any such distinction. This blind spot is not accidental. It is the essence of post-classical economics. And it explains why Europe is so crippled.

The way in which the euro was created in 1999 reflects this shallow vision. The Maastricht fiscal and financial rules maximize the commercial loan market by preventing central banks from supplying governments (and hence, the economy) with credit to grow. Commercial banks are to be the sole source of financing budget deficits – defined to include infrastructure investment in transportation, communication, power and water. Privatization of these basic services blocks governments from supplying them at subsidized rates or freely. So roads are turned into toll roads, charging access fees that are readily monopolized. Economies are turned into sets of tollbooths, paying out their access charges as interest to creditors. These extractive rents make privatized economies high-cost. But to the financial sector that is “wealth creation.” It is enhanced by untaxing interest payments to banks and bondholders – aggravating fiscal deficits in the process, however.

The Greek budget crisis in perspective

A fiscal legacy of the colonels’ 1967-74 junta was tax evasion by the well to do. The “business-friendly” parties that followed were reluctant to tax the wealthy. A 2010 report stated that nearly a third of Greek income was undeclared, with “fewer than 15,000 Greeks declar[ing] incomes of over €100,000, despite tens of thousands living in opulent wealth on the outskirts of the capital. A new drive by the Socialists to track down swimming pool owners by deploying Google Earth was met with a virulent response as Greeks invested in fake grass, camouflage and asphalt to hide the tax liabilities from the spies in space.” [1]

As a result of the military dictatorship depressing public spending below the European norm, infrastructure needed to be rebuilt – and this required budget deficits. The only way to avoid running them would have been to make the rich pay the taxes they were supposed to. But squeezing public spending to the level that wealthy Greeks were willing to pay in taxes did not seem politically feasible. (Almost no country since the 1980s has enacted Progressive Era tax policies.) The 3% Maastricht limit on budget deficits refused to count capital spending by government as capital formation, on the ideological assumption that all government spending is deadweight waste and only private investment is productive.

The path of least resistance was to engage in fiscal deception. Wall Street bankers helped the “conservative” (that is, fiscally regressive and financially profligate) parties conceal the extent of the public debt with the kind of junk accounting that financial engineers had pioneered for Enron. And as usual when financial deception in search of fees and profits is concerned, Goldman Sachs was in the middle. In February 2010, the German magazine Der Spiegel exposed how the firm had helped Greece conceal the rise in public debt, by mortgaging assets in a convoluted derivatives deal – legal but with the covert intent of circumventing the Maastricht limitation on deficits. “Eurostat’s reporting rules don’t comprehensively record transactions involving financial derivatives,” so Greece’s obligation appeared as a cross-currency swap rather than as a debt. The government used off-balance-sheet entities and derivatives similar to what Icelandic and Irish banks later would use to indulge in fictitious debt disappearance and an illusion of financial solvency.

The reality, of course, was a virtual debt. The government was obligated to pay Wall Street billions of euros out of future airport landing fees and the national lottery as “the so-called cross currency swaps … mature, and swell the country’s already bloated deficit.” [2] Translated into straightforward terms, the deal left Greece’s public-sector budget deficit at 12 percent of GDP, four times the Maastricht limit.

Using derivatives to engineer Enron-style accounting enabled Greece to mask a debt as a market swap based on foreign currency options, to be unwound over ten to fifteen years. Goldman was paid some $300 million in fees and commissions for its aid orchestrating the 2001 scheme. “A similar deal in 2000 called Ariadne devoured the revenue that the government collected from its national lottery. Greece, however, classified those transactions as sales, not loans.” [3] JPMorgan Chase and other banks helped orchestrate similar deals across Europe, providing “cash upfront in return for government payments in the future, with those liabilities then left off the books.”

The financial sector has an interest in understating the debt burden – first, by using “mark to model” junk accounting, and second, by pretending that the debt burden can be paid without disrupting economic life. Financial spokesmen from Tim Geithner in the United States to Dominique Strauss-Kahn at the IMF claimed that the post-2008 debt crisis is merely a short-term “liquidity problem” (lack of “confidence”), not insolvency reflecting an underlying inability to pay. Banks promise that everything will be all right when the economy “returns to normal” – if only the government will buy their junk mortgages and bad loans (“sound long-term investments”) for ready cash.

The intellectual deception at work

Financial lobbyists seek to distract voters and policy makers from realizing that “normalcy” cannot be restored without wiping out the debts that have made the economy abnormal. The larger the debt burden grows, the more economy-wide austerity is required to pay debts to banks and bondholders instead of investing in capital formation and real growth.

Austerity makes the problem worse, by intensifying debt deflation. To pretend that austerity helps economies rather than destroys them, bank lobbyists claim that shrinking markets will lower wage rates and “make the economy more competitive” by “squeezing out the fat.” But the actual “fat” is the debt overhead – the interest, amortization, financial fees and penalties built into the cost of doing business, the cost of living and the cost of government.

When difficulty arises in paying debts, the path of least resistance is to provide more credit – to enable debtors to pay. This keeps the system solvent by increasing the debt overhead – seemingly an oxymoron. As financial institutions see the point approaching where debts cannot be paid, they try to get “senior creditors” – the ECB and IMF – to lend governments enough money to pay, and ideally to shift risky debts onto the government (“taxpayers”). This gets them off the books of banks and other large financial institutions that otherwise would have to take losses on Greek government bonds, Irish bank obligations bonds, etc., just as these institutions lost on their holdings of junk mortgages. The banks use the resulting breathing room to try and dump their bond holdings and bad bets on the proverbial “greater fool.”

In the end the debts cannot be paid. For the economy’s high-financial managers the problem is how to postpone defaults for as long as possible – and then to bail out, leaving governments (“taxpayers”) holding the bag, taking over the obligations of insolvent debtors (such as A.I.G. in the United States). But to do this in the face of popular opposition, it is necessary to override democratic politics. So the divestment by erstwhile financial losers requires that economic policy be taken out of the hands of elected government bodies and transferred to those of financial planners. This is how financial oligarchy replaces democracy.

Paying higher interest for higher risk, while protecting banks from losses

The role of the ECB, IMF and other financial oversight agencies has been to make sure that bankers got paid. As the past decade of fiscal laxity and deceptive accounting came to light, bankers and speculators made fortunes jacking up the interest rate that Greece had to pay for its increasing risk of default. To make sure they did not lose, bankers shifted the risk onto the European “troika” empowered to demand payment from Greek taxpayers.

Banks that lent to the public sector (at above-market interest rates reflecting the risk), they were to be bailed out at public expense. [4] Demanding that Greece not impose a “haircut” on creditors, the ECB and related EU bureaucracy demanded a better deal for European bondholders than creditors received from the Brady bonds that resolved Latin American and Third World debts in the 1980s. In an interview with the Financial Times, ECB executive board member Lorenzo Bini Smaghi insisted:

First, the Brady bonds solution was a solution for American banks, which were basically allowed not to ‘mark to market’ the restructured bonds. There was regulatory forbearance, which was possible in the 1980 but would not be possible today.

Second, the Latin American crisis was a foreign debt crisis. The main problem in the Greek crisis is Greece, its banks and its own financial system. Latin America had borrowed in dollars and the lines of credit were mainly with foreigners. Here, a large part of the debt is with Greeks. If Greece defaulted, the Greek banking system would collapse. It would then need a huge recapitalization – but where would the money come from?

Third, after default the Latin American countries still had a central bank that could print money to pay for civil servants’ wages, pensions. They did this and created inflation. So they got out [of the crisis] through inflation, depreciation and so forth. In Greece you would not have a central bank that could finance the government, and it would have to partly shut down some of its operations, like the health system.

Mr. Bini Smaghi threatened that Europe would destroy the Greek economy if it tried to scale back its debts or even stretch out maturities to reflect the ability to pay. Greece’s choice was between or anarchy. Restructuring would not benefit “the Greek people. It would entail a major economic, social and even humanitarian disaster, within Europe. Orderly implies things go smoothly, but if you wipe out the banking system, how can it be smooth?” The ECB’s “position [is] based on principle … In the euro area debts have to be repaid and countries have to be solvent. That has to be the principle of a market-based economy.” [5]

A creditor-oriented economy is not really a market-based, of course. The banks destroyed the market by their own central financial planning — using debt leverage to leave Greece with a bare choice: Either it would permit EU officials to come in and carve up its economy, selling its major tourist sites and monopolistic rent-extracting opportunities to foreign creditors in a gigantic national foreclosure movement, or it could bite the bullet and withdraw from the Eurozone. That was the deal Mr. Bini Smaghi offered: “if there are sufficient privatizations, and so forth – then the IMF can disburse and the Europeans will do their share. But the key lies in Athens, not elsewhere. The key element for the return of Greece to the market is to stop discussions about restructuring.”

One way or another, Greece would lose, he explained: “default or restructuring would not help solve the problems of the Greek economy, problems that can be solved only by adopting the kind of structural reforms and fiscal adjustment measures included in the programme. On the contrary it would push Greece into a major economic and social depression.” This leverage demanding to be paid or destroying the economy’s savings and monetary system is what central bankers call a “rescue,” or “restoring market forces.” Bankers claim that austerity will revive growth. But to accept as a realistic democratic alternative would be self-immolation.

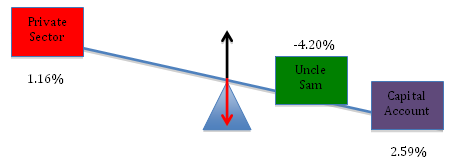

Unless Greece signed onto this nonsense, neither the ECB nor the IMF would extend loans to save its banking system from insolvency. On May 31, 2011, Europe agreed to provide $86 billion in euros if Greece “puts off for the time being a restructuring, hard or soft, of Greece’s huge debt burden.” [6] The pretense was a “hope that in another two years Greece will be in a better position to repay its debts in full.” Anticipation of the faux rescue led the euro to rebound against foreign currencies, and European stocks to jump by 2%. Yields on Greek 10-year bonds fell to “only” a 15.7 percent distress level, down one percentage point from the previous week’s high of 16.8 percent when a Greek official made the threatening announcement that “Restructuring is off the table. For now it is all about growth, growth, growth.”

How can austerity be about growth? This idea never has worked, but the pretense was on. The EU would provide enough money for the Greek government to save bondholders from having to suffer losses. The financial sector supports heavy taxpayer expense as long as the burden does not fall on itself or its main customers in the real estate sector or the infrastructure monopolies being privatized.

The loan-for-privatization tradeoff was called “aiding Greece” rather than bailing out German, French and other bondholders. But financial investors knew better. “Since the crisis began, 60 billion euros in deposits have been withdrawn from Greek banks, about a quarter of the country’s output.” [7] These withdrawals, which were gaining momentum, were the precise size of the loan being offered!

Meanwhile, the shift of 60 billion euros off the balance sheets of banks onto the private sector threatened to raise the ratio of public debt to GDP over 150 percent. There was talk that another 100 billion euros would be needed to “socialize the losses” that otherwise would be suffered by German, French and other European bankers who had their eyes set on a windfall if heavily discounted Greek bonds were made risk-free by carving up Greece in much the same way that the Versailles Treaty did to Germany after World War I.

The Greek population certainly saw that the world was at financial war. Increasingly large crowds gathered each day to protest in Syntagma Square in front of the Parliament, much as Icelandic crowds had done earlier under similar threats by their Social Democrats to sell out the nation to European creditors. And just as Iceland’s Prime Minister Sigurdardottir held on arrogantly against public opinion, so did Greek Socialist Prime Minister George Papandreou. This prompted EU Fisheries Commissioner Maria Damanaki “to ‘speak openly’ about the dilemma facing her country,” warning: “The scenario of Greece’s exit from the euro is now on the table, as are ways to do this. Either we agree with our creditors on a programme of tough sacrifices and results … or we return to the drachma. Everything else is of secondary importance.” [8] And former Dutch Finance Minister Willem Vermeend wrote in De Telegraaf that ‘Greece should leave the euro,’ given that it will never be able to pay back its debt.” [9]

As in Iceland, the Greek austerity measures are to be put to a national referendum – with polls reporting that some 85 percent of Greeks reject the bank-bailout-cum-austerity plan. Its government is paying twice as much for credit as the Germans, despite seemingly having no foreign-exchange risk (using the euro). The upshot may be to help drive Greece out of the eurozone, not only by forcing default (the revenue is not there to pay) but by Newton’s Third Law of Political Motion: Every action creates an equal and opposite reaction. The ECB’s attempt to make Greek labor –(“taxpayers”) pay foreign bondholders is leading to pressure for outright repudiation and the domestic “I won’t pay” movement. Greece’s labor movement always has been strong, and the debt crisis is further radicalizing it.

The aim of commercial banks is to replace governments in creating money, making the economy entirely dependent on them, with public borrowing creating an enormous risk-free “market” for interest-bearing loans. It was to overcome this situation that the Bank of England was created in 1694 – to free the country from reliance on Italian and Dutch credit. Likewise the U.S. Federal Reserve, for all its limitations, was founded to enable the government to create its own money. But European banks have hog-tied their governments, replacing Parliamentary democracy with dictatorship by the ECB, which is blocked constitutionally from creating credit for governments – until German and French banks found it in their own interest for it to do so. As UMKC Professor Bill Black summarizes the situation:

A nation that gives up its sovereign currency by joining the euro gives up the three most effective means of responding to a recession. It cannot devalue its currency to make its exports more competitive. It cannot undertake an expansive monetary policy. It does not have any monetary policy and the EU periphery nations have no meaningful influence on the ECB’s monetary policies. It cannot mount an appropriately expansive fiscal policy because of the restrictions of the EU’s growth and stability pact. The pact is a double oxymoron – preventing effective counter-cyclical fiscal policies harms growth and stability throughout the Eurozone.

Financial politics are now dominated by the drive to replace debt defaults by running a fiscal surplus to pay bankers and bondholders. The financial system wants to be paid. But mathematically this is impossible, because the “magic of compound interest” outruns the economy’s ability to pay – unless central banks flood asset markets with new bubble credit, as U.S. policy has done since 2008. When debtors cannot pay, and when the banks in turn cannot pay their depositors and other counterparties, the financial system turns to the government to extract the revenue from “taxpayers” (not the financial sector itself). The policy bails out insolvent banks by plunging domestic economies into debt deflation, making taxpayers bear the cost of banks gone bad.

These financial claims are virtually a demand for tribute. And since 2010 they have been applied to the PIIGS countries. The problem is that revenue used to pay creditors is not available for spending within the economy. So investment and employment shrink, and defaults spread. Something must give, politically as well as economically as society is brought back to the “Copernican problem”: Will the “real” economy of production and consumption revolve around finance, or will financial demands for interest devour the economic surplus and begin to eat into the economy?

Technological determinists believe that technology drives. If this were so, rising productivity would have made everybody in Europe and the United States wealthy by now, rich enough to be out of debt. But there is a Chicago School inquisition insisting that today’s needless suffering is perfectly natural and even necessary to rescue economies by saving their banks and debt overhead – as if all this is the economic core, not wrapped around the core.

Meanwhile, economies are falling deeper into debt, despite rising productivity measures. The seeming riddle has been explained many times, but is so counter-intuitive that it elicits a wall of cognitive dissonance. The natural view is to think that the world shouldn’t be this way, letting credit creation load down economies with debt without financing the means to pay it off. But this imbalance is the key dynamic defining whether economies will grow or shrink.

John Kenneth Galbraith explained that banking and credit creation is so simple a principle that the mind rejects it – because it is something for nothing, the proverbial free lunch stemming from the principle of banks creating deposits by making loans. Just as nature abhors a vacuum, so most people abhor the idea that there is such a thing as a free lunch. But the financial free lunchers have taken over the political system.

They can hold onto their privilege and avert a debt write-down only as long as they can prevent widespread moral objection to the idea that the economy is all about saving creditor claims from being scaled back to the economy’s ability to pay – by claiming that the financial brake is actually the key to growth, not a free transfer payment.

The upcoming Greek referendum poses this question just as did Iceland’s earlier this spring. As Yves Smith recently commented regarding the ECB’s game of chicken as to whether Greece’s government would accept or reject its hard terms:

This is what debt slavery looks like on a national level. …

Greece looks to be on its way to be under the boot of bankers just as formerly free small Southern farmers were turned into “debtcroppers” after the US Civil War. Deflationary policies had left many with mortgage payments that were increasingly difficult to service. Many fell into “crop lien” peonage. Farmers were cash starved and pledged their crops to merchants who then acted in an abusive parental role, being given lists of goods needed to operate the farm and maintain the farmer’s family and doling out as they saw fit. The merchants not only applied interest to the loans, but further sold the goods to farmers at 30% or higher markups over cash prices. The system was operated, by design, so that the farmer’s crop would never pay him out of his debts (the merchant as the contracted buyer could pay whatever he felt like for the crop; the farmer could not market it to third parties). This debt servitude eventually led to rebellion in the form of the populist movement. [10]

One would expect a similar political movement today. And as in the late 19th century, academic economics will be mobilized to reject it. Subsidized by the financial sector, today’s economic orthodoxy finds it natural to channel productivity gains to the finance, insurance and real estate (FIRE) sector and monopolies rather than to raise wages and living standards. Neoliberal lobbyists and their academic mascots dismiss sharing productivity gains with labor as being unproductive and not conducive to “wealth creation” financial style.

Making governments pay creditors when banks run aground

At issue is not only whether bank debts should be paid by taking them onto the public balance sheet at taxpayer expense, but whether they can reasonably be paid. If they cannot be, then trying to pay them will shrink economies further, making them even less viable. Many countries already have passed this financial limit. What is now in question is a political step – whether there is a limit to how much further creditor interests can push national populations into debt-dependency. Future generations may look back on our epoch as a great Social Experiment on how far the point may be deferred at which government – or parliaments – will draw a line against taking on public liability for debts beyond any reasonable capacity to pay without drastically slashing public spending on education, health care and other basic services?

Is a government – or economy – be said to be solvent as long as it has enough land and buildings, roads, railroads, phone systems and other infrastructure to sell off to pay interest on debts mounting exponentially? Or should we think of solvency as existing under existing proportions in our mixed public/private economies? If populations can be convinced of the latter definition – as those of the former Soviet Union were, and as the ECB, EU and IMF are now demanding – then the financial sector will proceed with buyouts and foreclosures until it possesses all the assets in the world, all the hitherto public assets, corporate assets and those of individuals and partnerships.

This is what today’s financial War of All against All is about. And it is what the Greeks gathering in Syntagma Square are demonstrating about. At issue is the relationship between the financial sector and the “real” economy. From the perspective of the “real” economy, the proper role of credit – that is, debt – is to fund productive capital investment and economic growth. After all, it is out of the economic surplus that interest is to be paid. This requires a tax system and financial regulatory system to maximize the growth. But that is precisely the fiscal policy that today’s financial sector is fighting against. It demands tax-deductibility for interest, encouraging debt financing rather than equity. It has disabled truth-in-lending laws and regulation keeping prices (the interest rate and fees) in line with costs of production. And it blocks governments from having central banks to freely finance their own operations and provide economies with money.

Banks and their financial lobbyists have not shown much interest in economy-wide wellbeing. It is easier and quicker to make money by being extractive and predatory. Fraud and crime pay, if you can disable the police and regulatory agencies. So that has become the financial agenda, eagerly endorsed by academic spokesmen and media ideologues who applaud bank managers and subprime mortgage brokers, corporate raiders and their bondholders, and the new breed of privatizers, using the one-dimensional measure of how much revenue can be squeezed out and capitalized into debt service. From this neoliberal perspective, an economy’s wealth is measured by the magnitude of debt obligations – mortgages, bonds and packaged bank loans – that capitalize income and even hoped-for capital gains at the going rate of interest.

Iceland belatedly decided that it was wrong to turn over its banking to a few domestic oligarchs without any real oversight or regulation over their self-dealing. From the vantage point of economic theory, was it not madness to imagine that Adam Smith’s quip about not relying on the benevolence of the butcher, brewer or baker for their products, but on their self-interest is applicable to bankers? Their “product” is not a tangible consumption good, but interest-bearing debt. These debts are a claim on output, revenue and wealth; they do not constitute real wealth.

This is what pro-financial neoliberals fail to understand. For them, debt creation is “wealth creation” (Alan Greenspan’s favorite euphemism) when credit – that is, debt – bids up prices for property, stocks and bonds and thus enhances financial balance sheets. The “equilibrium theory” that underlies academic orthodoxy treats asset prices (financialized wealth) as reflecting a capitalization of expected income. But in today’s Bubble Economy, asset prices reflect whatever bankers will lend. Rather than being based on rational calculation, their loans are based on what investment bankers are able to package and sell to frequently gullible financial institutions. This logic leads to attempts to pay pensions out of a “wealth creating” process that runs economies into debt.

It is not hard to statistically illustrate this. There amount of debt that an economy can pay is limited by the size of its surplus, defined as corporate profits and personal income for the private sector, and net fiscal revenue paid to the public sector. But neither today’s financial theory nor global practice recognizes a capacity-to-pay constraint. So debt service has been permitted to eat into capital formation and reduce living standards – and now, to demand privatization sell-offs.

As an alternative is to such financial demands, Iceland has provided a model for what Greece may do. Responding to British and Dutch demands that its government guarantee payment of the Icesave bailout, the Althing recently asserted the principle of sovereign debt:

The preconditions for the extension of government guarantee according to this Act are:

1. That … account shall be taken of the difficult and unprecedented circumstances with which Iceland is faced with and the necessity of deciding on measures which enable it to reconstruct its financial and economic system.

This implies among other things that the contracting parties will agree to a reasoned and objective request by Iceland for a review of the agreements in accordance with their provisions.

2. That Iceland’s position as a sovereign state precludes legal process against its assets which are necessary for it to discharge in an acceptable manner its functions as a sovereign state.

Instead of imposing the kind of austerity programs that devastated Third World countries from the 1970s to the 1990s and led them to avoid the IMF like a plague, the Althing is changing the rules of the financial system. It is subordinating Iceland’s reimbursement of Britain and Holland to the ability of Iceland’s economy to pay:

In evaluating the preconditions for a review of the agreements, account shall also be taken to the position of the national economy and government finances at any given time and the prospects in this respect, with special attention being given to foreign exchange issues, exchange rate developments and the balance on current account, economic growth and changes in gross domestic product as well as developments with respect to the size of the population and job market participation.

This is the Althing proposal to settle its Icesave bank claims that Britain and the Netherlands rejected so passionately as “unthinkable.” So Iceland said, “No, take us to court.” And that is where matters stand right now.

Greece is not in court. But there is talk of a “higher law,” much as was discussed in the United States before the Civil War regarding slavery. At issue today is the financial analogue, debt peonage.

Will it be enough to change the world’s financial environment? For the first time since the 1920s (as far as I know), Iceland made the capacity-to-pay principle the explicit legal basis for international debt service. The amount to be paid is to be limited to a specific proportion of the growth in its GDP (on the admittedly tenuous assumption that this can indeed be converted into export earnings). After Iceland recovers, the Treasury offered to guarantee payment for Britain for the period 2017-2023 up to 4% of the growth of GDP after 2008, plus another 2% for the Dutch. If there is no growth in GDP, there will be no debt service. This meant that if creditors took punitive actions whose effect is to strangle Iceland’s economy, they wouldn’t get paid.

No wonder the EU bureaucracy reacted with such anger. It was a would-be slave rebellion. Returning to the applicable of Newton’s Third Law of motion to politics and economics, it was natural enough for Iceland, as the most thoroughly neoliberalized disaster area, to be the first economy to push back. The past two years have seen its status plunge from having the West’s highest living standards (debt-financed, as matters turn out) to the most deeply debt-leveraged. In such circumstances it is natural for a population and its elected officials to experience a culture shock – in this case, an awareness of the destructive ideology of neoliberal “free market” euphemisms that led to privatization of the nation’s banks and the ensuing debt binge.

The Greeks gathering in Syntagma Square seem to need no culture shock to reject their Socialist government’s cave-in to European bankers. It looks like they may follow Iceland in leading the ideological pendulum back toward a classical awareness that in practice, this rhetoric turns out to be a junk economics favorable to banks and global creditors. Interest-bearing debt is the “product” that banks sell, after all. What seemed at first blush to be “wealth creation” was more accurately debt-creation, in which banks took no responsibility for the ability to pay. The resulting crash led the financial sector to suddenly believe that it did love centralized government control after all – to the extent of demanding public-sector bailouts that would reduce indebted economies to a generation of fiscal debt peonage and the resulting economic shrinkage.

As far as I am aware, this agreement is the first since the Young Plan for Germany’s reparations debt to subordinate international debt obligations to the capacity-to-pay principle. The Althing’s proposal spells this out in clear terms as an alternative to the neoliberal idea that economies must pay willy-nilly (as Keynes would say), sacrificing their future and driving their population to emigrate in a vain attempt to pay debts that, in the end, can’t be paid but merely leave debtor economies hopelessly dependent on their creditors. In the end, democratic nations are not willing to relinquish political planning authority to an emerging financial oligarchy.

No doubt the post-Soviet countries are watching, along with Latin American, African and other sovereign debtors whose growth has been stunted by predatory austerity programs imposed by IMF, World Bank and EU neoliberals in recent decades. We should all hope that the post-Bretton Woods era is over. But it won’t be until the Greek population follows that of Iceland in saying no – and Ireland finally wakes up.

Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf writes that the eurozone “has only two options: to go forwards towards a closer union or backwards towards at least partial dissolution. … either default and partial dissolution or open-ended official support.” [11] But ECB intransigence leaves little alternative to breakup. Europe’s payments-surplus nations are waging financial war against the deficit countries. Without a common union based on mutual support within a mixed economy – one capable of checking financial aggression – the European Central Bank replaced the military high command. Its bold gamble is whether the Greeks will be as stupid as the Irish, not as smart as the Icelanders.

[1] Helena Smith, “The Greek spirit of resistance turns its guns on the IMF,” The Observer, May 9, 2010.

[2] Beat Balzli, “How Goldman Sachs Helped Greece to Mask its True Debt,” Der Spiegel, February 8, 2010. The report adds: “One time, gigantic military expenditures were left out, and another time billions in hospital debt.”

[3] Louise Story, Landon Thomas Jr. and Nelson D. Schwartz, “Wall St. Helped to Mask Debt Fueling Europe’s Crisis,” The New York Times, February 13, 2010.

[4] At the time of the spring 2010 bailout French banks held €31 billion of Greek bonds, compared to €23 billion by German banks. This helps explain why French President Nicolas Sarkozy sought to take major credit for the bailout, based on a May 7, 2010 discussions with EU Commission President José Manuel Barroso, ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet and Eurogroup President Jean-Claude Juncker.

[5] Ralph Atkins, “Transcript: Lorenzo Bini Smaghi,” Financial Times, May 30, 2011. The interview took place on May 27.

[6] Landon Thomas Jr., “New Rescue Package for Greece Takes Shape,” The New York Times, June 1, 2011.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Emma Rowley, “Greece risks ‘return to drachma,’” The Telegraph, June 1, 2011.

[9] Idris Francis, “Greece leaving the EMU: From taboo to fashionable?” Open Europe blog, June 1, 2011. (I am indebted to Paul Craig Roberts for drawing my attention to this source.)

[10] Yves Smith, “Will Greeks Defy Rape and Pillage By Barbarians Bankers? An E-Mail from Athens,” Naked Capitalism, May 30, 2011.

[11] Martin Wolf, “Intolerable choices for the eurozone,” Financial Times, June 1, 2011