Greetings again from Ireland. One of the many mysteries about the current crisis is why anyone listens to the IMF or anyone that supported its anti-regulatory policies. Prior to the crisis, even the IMF had begun to confess that its austerity programs made poor nations’ financial crises worse. In the lead up to the crisis the IMF was blind to the developing crises. It even praised nations like Ireland during the run up to the crisis, missing the largest bubble (relative to GDP) of any nation, an epidemic of banking control fraud, and the destruction of any pretense to effective Irish banking regulation.

Crises reveal many deficiencies and one of the most glaring was the European Central Bank (ECB). The ECB was set up, unlike the Federal Reserve, to have only one mission and one function – securing price stability through monetary policy. The Fed has three missions and three primary functions. The missions are systemic financial stability, price stability, and full employment. The functions are conducting monetary policy, serving as the lender of last resort, and acting as a financial supervisor. The crisis revealed that both dominant forms of central banking could attain their most fervent goal – near total “independence” in determining and conducting monetary policy – and fail abjectly.

The crisis revealed that the ECB’s narrow mission and function left the EU helpless to deal with a severe economic crisis. The ECB could not save Europe. Only the Fed could, and did, save Europe through currency swaps, serving as a lender of last resort (often on the basis of chimerical collateral) to major European banks, and providing liquidity backstops to myriad financial markets.

The central financial crisis caused a series of national crises in the European periphery, initially in Iceland and Latvia. Individual European nations whose creditors were most at risk joined with the IMF to “bail out” these initial failures. The “bail outs,” however, followed the old, destructive IMF playbook. Greece then slid abruptly into crisis when the new socialist government revealed that its predecessor conservative government (sometimes with the aid of God’s dragoons – Goldman Sachs) had been lying about Greece’s budget deficit for years. The bond markets were not amused and demanded far higher interest rates on Greek debt. Far higher interest rates, for a nation already in deep deficit and lacking any sovereign currency, could only create a destructive feedback cycle that would end in default. The EU’s leaders believed that the future of the euro and perhaps the EU were at risk, so they demanded that the ECB step forward to save Greece.

The ECB could not, under its long-held view of its own rules, save Greece. The ECB reinterpreted its rules to create a second mission and a second function to (belatedly) respond to the EU’s sovereign debt crisis. The ECB became a lender of last resort to euro members. (EU members that retain sovereign currencies with floating values such as the UK are not subject to any involuntary default risk. They can always pay debts denominated in their own currency.)

The ECB managed to get nearly everything wrong in its dealings with Greece. Even the IMF is distressed by the ECB’s response to the crises of the periphery. The first problem was the most understandable. The ECB took too long to respond to the Greek crisis. Delay was inevitable because the ECB did not have a “lender of last resort” program and had taken the position that it could not and should not have such a program because its sole mission and function were achieving price stability through monetary policy. Nevertheless, delay was very harmful. Greece twisted slowly in the wind, taking substantial economic damage. The ECB appeared to lack decisiveness. Speculation arose that other nations on the EU periphery would also need help from the ECB, which led to attacks on their sovereign debt issuances and damage to their budgets and economies.

The ECB compounded the problem by “aiding” Greece by making it loans. Greece’s problems included excessive debt and no sovereign currency, so the ECB’s aid deepened its debt crisis. The ECB did not give Greece grants, which is what it needed. Giving Greece real financial aid, rather than loans was a bridge too far for the ECB. Greece popped a second EU bubble. The second bubble was hyper-inflated by hot air from European politicians (particularly the French and Germans) claiming that the EU and euro were leading the member nations to ever greater political integration and, ultimately, a true “union.” Well, no. Not even close. The EU is moving in the opposite direction. As the Irish columnist David McWilliams aptly observed, it turned out that the Germans didn’t think of the Greeks like the rest of America thought of New Orleans when it was devastated by Hurricane Katrina. They weren’t fellow citizens entitled to draw on the nation’s resources to recover. The French and Germans, the leading proponents of ever greater European unity and solidarity, viewed the crisis as the Greeks’ fault and they believed that the Greeks should pay a stiff price for resolving the self-inflicted crisis.

The ECB’s third error was to “channel” IMF policies and demand that Greece – a nation is serious recession – adopt financial austerity during the recession. This, predictably, intensified a recession. The ECB insisted on the same medicine for Ireland and Portugal – and increased unemployment in both nations. Spain, which the ECB is pretending is sound, is covering up its banking crisis. By keeping its real estate values massively inflated Spain is preventing the markets from clearing. Unemployment is 20 (29% in Andalusia and 45% for you young adults). The ruling Socialist party was just crushed in a series of regional elections and will likely fall once national elections occur. Ireland’s and Portugal’s ruling parties fell. Economic stability generates political instability.

One of the great paradoxes is that the periphery’s generally left-wing governments adopted so enthusiastically the ECB’s ultra-right wing economic nostrums – austerity is an appropriate response to a great recession. Even neoclassical economists know that the ECB’s policies towards the periphery are insane. The IMF and ECB impose pro-cyclical policies that make recessions worse. Embracing theoclassical economics isn’t simply harmful to the economy, it’s also political suicide. Why left-wing parties embrace the advice of the ultra-right wing economists whose anti-regulatory dogmas helped cause the crisis is one of the great mysteries of life. Their policies are self-destructive to the economy and suicidal politically. Lemmings don’t really follow each other and jump off cliffs – that’s fiction. Left-wing European governments, however, continue to support the ultra-right wing policies that the ECB pushes even when they know those policies will harm the economy and cause the left-wing party to be crushed in the next general election. They watch the ECB’s policies fail and their sister parties lose power and then they step forward to do the same.

Fianna Fail, Ireland’s ruling party during the initial crises is only vaguely left-wing, but it won the prize for the worst response to a banking crisis in modern Europe. It remains so clueless that last I checked its website it still boasted:

“The measures we have taken have been commended by international bodies such as the European Central Bank, the European Commission, the IMF and the OECD and the approval of the international markets.”

The old, and very true, line is that there is always at least one fool in a poker game and if you cannot identify the fool within five minutes of joining the game it’s because you are the fool. Ireland has played the fool in its response to the banking and sovereign debt crises. Fianna Fail, gratuitously, turned a banking crisis into a budgetary and sovereign debt crisis and a severe recession into a economic trap that threatens to make Ireland a mini-Japan. Fianna Fail – even after it performed disastrously and was crushed in the general election – thinks it’s a good thing that the ECB and the IMF “commended” Fianna Fail’s policies. Fianna Fail would think it was a good thing if its poker rivals “commended” how well it played poker. Unfortunately, the Irish people provided Fianna Fail’s stakes in this real-world poker game with the Irish banks’ creditors, the ECB, and the IMF. Fianna Fail still thinks the ECB is Ireland’s friend. “Naïve” is inadequate as a descriptor.

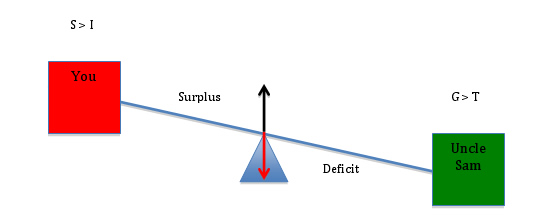

These three ECB errors combined with the inherent dangers that the euro poses for the periphery. A nation that gives up its sovereign currency by joining the euro gives up the three most effective means of responding to a recession. It cannot devalue its currency to make its exports more competitive. It cannot undertake an expansive monetary policy. It does not have any monetary policy and the EU periphery nations have no meaningful influence on the ECB’s monetary policies. It cannot mount an appropriately expansive fiscal policy because of the restrictions of the EU’s growth and stability pact. The pact is a double oxymoron – preventing effective counter-cyclical fiscal policies harms growth and stability throughout the Eurozone. The additional dangers include the German desire for a very strong euro, which makes it harder for the nations of the periphery to recover through exports. Germany’s ability to export even under a strong euro makes it even harder for the periphery to export. The one area of financial sovereignty that remains for the periphery is debt, and that can easily become a severe threat because, unlike a nation with a sovereign, floating currency, a nation that uses the euro can prove The surging interest expense can cause a feedback into budgetary pressures (brought on by the recession – and aggravated by the ECB austerity) that causes recurrent crises in individual nations and, through contagion, much of the periphery.

The ECB has recently compounded these inherent problems of the euro through six additional blunders. It has ruled out debt restructuring and made the argument against restructuring one of morality. The truth is that Greece and Iceland are insolvent. They cannot repay their liabilities. Trying to make them repay their liabilities will further harm their economies and increase ultimate losses. This is why we have bankruptcy laws. It is why the U.S. has non-draconian bankruptcy laws that allow a “fresh start.” This is one of the acts of American genius. It greatly increases entrepreneurial activity by individuals and businesses. It has allowed tens of millions of Americans and tens of thousands of businesses a second chance. Keeping a nation in a grinding economic crisis for a decade is pointlessly inhumane (particularly in a continent that claims to prize European solidarity). It is also self-destructive. It harms the periphery and the core by reducing economic growth and causing a wide range of severe social problems. It is a terrible policy for those that believe in the expansion of the EU to the remaining candidate states. Allowing a fresh start by restructuring debts (a euphemism for partial default) is simply good business. The ECB was foolish to take the best option off the table and to stigmatize it as a moral failure.

The ECB then made things worse in a third way by charging Greece and Ireland too much to borrow. The ECB could have finessed the entire “default” and “morality” rhetoric by providing Greece and Ireland with extremely low interest loans repayable over an extremely long time period. This, of course, would have provided a substantial subsidy to Greece and Ireland, which is exactly what they needed (and what the core needed to escape the crisis that was largely created by the core). Instead, the ECB has charged Greece and Ireland relatively high interest rates. Combined with their recessions, budgetary crises, loss of effective sovereign means to counter the recession because they were members of the euro, and the crippling effects of the ECB’s demands for austerity, the effect of the ECB loans has been to make Greece and Ireland’s debt burdens even more unsustainable.

The ECB’s fourth blunder was blaming the crises overwhelmingly on the periphery. That is overstated in the case of Greece and absurd in Ireland’s case. Ireland ran budgetary surpluses during the height of the lead up to the crisis. It has a budgetary crisis for three reasons. The primary reason is the Irish government’s gratuitous guarantee of the Irish banks’ debts. The secondary reason is the effect of a severe recession triggered by the banking crisis and exacerbated by the ECB’s demands for austerity. The banking crisis was largely the product of accounting control fraud by leading Irish banks. I will develop that analysis in future columns. The tertiary reason is the cost of repaying the ECB and IMF debt. Foreign banks played a dominant role in funding the Irish banking crisis and some of the fraudulent Irish banks. Foreign creditors, particularly foreign banks, were the leading beneficiaries of the insane decision by Fianna Fail to have the Irish people guarantee the Irish banks’ debts to these creditors. The ECB “bailout” of Ireland is in truth primarily a bailout of non-Irish creditors of Irish banks. Those non-Irish creditors are overwhelmingly financial institutions and disproportionately German financial institutions. I trust the reasons why Prime Minister Merkel has continued to support the “Irish bailout” despite the political damage it causes her party is now clear – the “Irish bailout” could more aptly be termed the “German bank bailout.”

The ECB should have explained these realities whenever it discussed the Irish crisis. What should have happened in Ireland, at the minimum, is that the four large, insolvent banks should have been treated as insolvent banks, which was the reality. Bank debts represent contracts. The contract that the Irish banks’ lenders entered into with the banks had these basic terms.

- We recognize that the loans we make to the Irish banks are not protected by deposit insurance except to the extent we make actual deposits in amounts less than or equal to the deposit insurance limit. (It is important to understand that several of the largest Irish banks were exceptional in how few insured deposits they had.)

- As to insured deposits, the contract was that Ireland, in the event the bank failed, would repay us the full amount of our deposit up to the insurance limit. In return, as insured depositors we accepted a lower interest rate from the banks because deposit insurance reduced our risk of loss if the bank failed.

- To the extent that we lend money to the bank other than through insured deposits we are at greater risk of loss if the bank fails so we are compensated for that risk by receiving a higher rate of interest than do insured depositors. If the bank fails we only get repaid a portion of our debts. That portion depends on how insolvent the banks prove to be. If the banks’ losses on assets are 60% (roughly the loss rate at the worst three Irish banks), then we will receive under 40 cents on the euro (because the administrative expenses of receivership will reduce the pro rata recovery of unsecured creditors). The recovery rate for general creditors becomes even smaller when the bank has secured creditors or other creditors with higher priorities (which can include depositors in the U.S. context). The Irish banks’ general creditor, therefore, already received compensation in the form of higher yield that they deemed adequate recompense for the taking the risk of catastrophic loss in the event the bank failed. To pay general creditors in full when the bank is deeply insolvent is to provide them with a windfall – and to create perverse incentives that would further erode “private market discipline” and make future crises more likely and more severe. The Irish banks’ creditors were supposed to suffer catastrophic losses when the banks failed – that was the deal they made and they decided that the extra yield was sufficient. No one made the creditors loan to the Irish banks. The creditors voluntarily did so to make a lot of euros.

- To the extent that we lent money to Irish banks on a subordinated basis the deal we made was that we would be wiped out entirely if the bank became insolvent. Indeed, that is why subordinated debt is allowed to be treated as tier II capital under the Basel accords. Again, neoclassical economists have claimed that subordinated (“sub”) debt provides the ideal form of capital because it self-selects for financially sophisticated lenders who have superb incentives and ability to provide effective private market discipline precisely because they know they will lose everything if the bank becomes insolvent. In practice, sub debt never provides effective private market discipline, but neoclassical economists cannot admit that. Neoclassical economists, therefore, argue that bailing out sub debt creates perverse incentives and makes future crises more likely and more destructive. Ireland provided a governmental guarantee that covered even the great bulk of the sub debt. (One potentially confusing term from the U.S. perspective used in Ireland is “senior debt.” Irish reports on their banks use this term to refer to general creditors’ claims that have no special priority. They are “senior” only relative to sub debt, not other general creditors.)

The overall impact of all of this is that if the ECB insists on talking in terms of morality and honoring contracts the uninsured creditors should have been the ones to bear the overwhelming bulk of the losses caused by the Irish banks’ insolvency. That’s what their contracts provided. Instead, they are reaping a massive windfall at the direct expense of the Irish people.

I must mention in passing a new analysis by Goldman Sachs related to this issue that is so exceptionally bad that it demands response.

State default would wipe out Ireland’s banks

Goldman figures show banks would take €12bn hit

By Nick Webb

Sunday May 29 2011

“IRISH banks would be all but wiped out if the Government was to default or restructure the State’s borrowings because of their vast holdings of Irish bonds and sovereign debt.

Bank of Ireland and Allied Irish Bank could face loses of as much as €11.4bn if a major haircut was part of any deal, according to a new report from Goldman Sachs, which has been obtained by the Sunday Independent.”

The only thing that these figures on Irish bond holdings demonstrate (which Goldman misses entirely) is what I have been explaining. The Irish government gratuitously bailed out massively insolvent Irish banks. The direct beneficiaries of this bailout included many foreign creditors, particularly banks, and more particularly German banks. The Irish government, because it lacks a sovereign currency and because it has guaranteed these massive debts, is short of euros. The Irish government, therefore, gave the banks Irish bonds. The Irish banks already had some Irish bonds in portfolio. Irish bonds have large market losses because Ireland is insolvent and if it follows the ECB’s austerity dictates it will become more insolvent. (Eurozone bank stress tests excluded sovereign debt risks because they were designed not to be very stressful.)

The title of the article, therefore, is misleading. Ireland’s insolvent banks were “wiped out” years ago when they made epic bad and fraudulent loans. Ireland is insolvent and it does not have a sovereign currency; it cannot afford to convert currently its sovereign debt held by its banks into euros. Ireland’s problem, therefore, is not the consequences of defaulting, but the consequences of failing to default.

Goldman is doubly wrong about a debt default causing the failure of the banks. I’ve explained why this claim reverses causality. One, it was the failure of the banks and the insane guarantee that caused the budgetary and sovereign debt crisis and the greatly increased “funding” of the banks with Irish bonds. It was the failure of the banks and the guarantee that made Ireland insolvent and (absent real aid from the EU) makes some form of Irish default inevitable.

Two, an Irish debt default would not cause the banks to fail (assuming counterfactually that they hadn’t already failed). If Ireland leaves the euro and reestablishes a floating, sovereign currency the Irish banks’ holdings of Irish bonds will be irrelevant. The fact that AIB and the Bank of Ireland hold Irish debt does not impose any net cost on the Irish government of repudiating debt. Ireland, should it find it desirable, can simply provide AIB and the Bank of Ireland with new Irish bonds or with the new, sovereign Irish currency. The only real issue is whether, and to what extent, it makes sense for the Irish government to subsidize AIB and the Bank of Ireland and what it should receive in return for such aid.

The fifth EU blunder has not been limited to the ECB. A series of EU representatives and parliamentarians of individual nation states have decided to demonize the periphery and to “suggest” that the periphery act in a manner designed to humiliate the nations, impair their sovereignty, and create intense enmity towards the core nations. Greece has been told to sell it islands and beaches. This has led to media speculation that it is being asked to sell its national archeological treasures. Prominent representatives of the core nations regularly deride the purported national character flaws of the periphery. The ECB strategy for the recovery of the periphery is for those nations to engage in a “race to the bottom” of wages to “restore competitiveness.” The core has consigned the periphery to a second track – and their track is the road to Bangladeshi salaries.

The sixth EU blunder is to threaten not only the periphery but other EU and transnational institutions. The ECB, last week, threatened to cut off all credit to the periphery if Greece entered into a debt restructuring deal brokered by the G-8 or any similar group. The ECB, the least democratic institution in the EU system, seeks to arrogate to itself unprecedented power over EU member nations when they are in crisis. This will produce riots, mass protests, and the return of anarchism in many parts of Europe. The one thing that the citizens of the core and the periphery share is the conviction that “the other” is acting wretchedly and in contravention of ideals underlying the formation and expansion of the EU. Neither the core nor the periphery understands the others’ perspective. The ECB has no idea how much rage it has created in the periphery and the passionate divisions it is creating among Europeans. If the ECB is not curbed it will destroy the European project. The ultimate irony is that it will be the Germans and French who dominate the ECB and represent the two nations that have been the strongest proponents of an ever closer union, who will fracture the union unless they give up their theoclassical dogmas.

(picture source: http://blog.brentbrown.com)